|

|

Area/Range |

|---|---|

|

|

64.04997°N / 16.94641°W |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Trad Climbing, Sport Climbing, Toprope, Bouldering, Ice Climbing, Mixed, Scrambling, Skiing |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

6919 ft / 2109 m |

|

|

Overview

| "It is a difficult question to answer, for the landscape was so different from anything I have seen in other countries, or even elsewhere in Iceland. I should imagine that no place on earth can show anything to correspond with it, and there was nothing that one has learnt to consider beautiful or ugly with which it could have been compared. It was quite unique, offering no single point of contact with any of the beauty-values that civilization has taught us." Geologist Professor Hans Wilhelmsson Ahlmann (1889 – 1974) on the area's natural beauty |

Skaftafell National Park is considered to be the jewel in the crown of Icelandic national parks, which is high praise for a country blessed with such a wide array of extraordinary landscapes. Even the most apathetic of visitors would have to concede that they were standing amongst something very special indeed. The park is an oasis in a desert of the black proglacial sandur; a green isle, whose valleys are home to many sparkling glacier, and whose lofty mountain tops reach towards the sky. Once one of the remotest parts of Iceland, since the opening of the Route 1 ring road in the 1970s the area has become one of the most popular tourist destinations in the country. Despite its popularity, the area remains unspoilt, with the only development having taken place at the southern edge of its boundary. Few visitors venture further than the Visitors Centre, and even fewer bother to travel further than the terminus of the Skaftafellsökull glacier, a short walk away. This leaves much to be recommended for the hiker or mountaineer who wishes to explore the park, and a short walk off the beaten track will lead to relative solitude, and the freedom to explore one of Europe’s finest mountain ranges.

The park is situated in the Öræfi area, between the villages of Kirkjubæjarklaustur in the west and Höfn in the east. It was established on September 15th 1967 by the Icelandic Government in conjunction with the World Wildlife Fund (now the World Wide Fund for Nature) and covered an area of around 500km2, mostly in the south. At this time the designation only protected the area around Skeiðarájökull, Skaftafellsjökull and Morsárjökull glaciers, as well as Skaftafellsheiði and Skaftafellsfjöll. On July 27th 1984 it was expanded to 1736km2 covering around 20% of Vatnajökull ice sheet, and more recently, on October 28th 2004 it was further extended to cover over half of the ice sheet, an area totalling 4807km2, making it the largest national park in Europe. In Iceland National Parks are designated for their unique landscape features, vegetation or animal life, or if they are a location of historic significance, Skaftafell falling into the former category. They are entirely owned by the government and are open, without the need of a permit, to anyone who wishes to visit them.

Landscape

The park’s landscape is a product of its glaciers and the erosion caused by the numerous rivers that flow from them. The valley glaciers of Skeiðarájökull, Skaftafellsjökull and Morsárjökull are among the most prominent features of the landscape, and the rivers Skeiðará, Skaftafellsá and Morsá emerge from them respectivly. Skeiðará is the largest, deepest and subsequently most dangerous of the three and was a considerable hindrance to travel until it was bridged in 1974 as part of the countries Route 1 ring road development, the closest thing Iceland has to a motorway. The river is known for great floods (jökulhlaup) caused by volcanic actitvity and geothermal heat under the ice around the Grímsvötn area.

The valley glaciers are all subsidiaries of the Vatnajökull ice sheet, the largest glacier in Iceland, most of which now falls within the boundary of the National Park (since 2004). The glacier has an area of over 8,100 km², but consistant with most glaciers in the region, it is currently in shrink mode. It covers a massive 8% of the country, and is the largest glacier in Europe by volume, and second only to the Austfonna ice cap on Nordaustlandet in the Svalbard archipelago, in terms of area. The average thickness of the ice is around 400m, with a maximum thickness of around 1,000m.

The park is home to the volcano Öræfajökull, which has a long history of significant eruptions, which, in some cases, have caused enourmous damage, and loss of life. The level of damage is of course relative, there isn’t a whole lot that can be damaged, when compared with Vesuvius for example. In 1362 the volcano erupted violently, producing the largest tephra fall in Iceland’s recoreded history. The event resulted in the destruction and complete abandonment of Litla-Hérað (the Little District). According to the Oddaverjaannall Chronicle, "no living beings survived apart from one old woman and a mare" in the parishes of Hof and Rauðilækur, after which the area was given the name Öræfi, which literally means an area without harbour, but soon after took the meaning wasteland in Icelandic. The area would not be resettled for another 40 years. At Bær, just south of Fagurhólsmýri, archaeologists have now excavated the remains of a village from a layer of ash deposited during the eruption, which has been nicknamed "the Icelandic Pompeii".

Falljökull (Photo by Brian Jenkins)

Falljökull (Photo by Brian Jenkins)The next major eruption occurred in 1727, and although smaller in magnitude, caused a number of deaths through jökulhlaps. Contemporary sources describe how it was impossible to tell night from day for days on end due to the ash fallout. The water released by the glacier burst following the eruption is estimated to have reached 100,000 m3/sec. - the same volume as the Amazon.

The last major eruption to occur in the park was the 1996 eruption of Grimsvötn, a 1713 m high volcano near the centre of Vatnajökull. On September 29th, 1996 at 10:48 an earthquake of magnitude 5 on the Richter scale was detected from the volcano Bardarbunga to the south, and was followed by a series of smaller events with intermittent larger quakes of magnitude 3-4. On the morning of October 1st an over flight discovered a subsidence bowl and cracks in the glacier surface, and on October 2nd, another flight observed that an eruption had broken through the ice in the form of a 4km long fissure along Grimsvötn’s north flank. Rhythmic explosions resulted in black ash clouds rising to a height of 500 m while the buoyant eruption column rose to 3000 m. On October 13th the Nordic Volcanological Institute announced that the eruption stopped and as of October 18th, there had been no signs of renewed activity. Melt water continued to flow towards the Grímsvötn caldera lake, and the water level in the caldera reached 150 feet (50 m) higher than the level at which glacier bursts typically occur.

The long awaited jokulhlaup started suddenly on the morning of November 5th, preceded by earthquake activity of unknown origin. The estimated flow was 6,000 cubic m/sec, and the outburst destroyed sections of the Route 1 ring road and the only bridge over connecting southeast with southwest Iceland. Luckily for the national park the jokulhlaup narrowly missed the visitor’s centre and only damaged the areas infrastructure, although the damaged caused was in excess of $12 million US. A piece of the destroyed bridge has been placed at a viewpoint at the side of the road, just before the turn off to the visitors centre. The jokulhlaup peaked late on November 5, and at its zenith nearly 45,000 cubic meters of water had discharged each second. By noon on November 6, the discharge had dropped to 15,000 cubic m/sec. The last time Grimsvötn erupted was on November 1st 2004 when a plume of steam and ash from an eruption was reported. This time there where no jokulhlaups

. Due to its close proximity to Öræfajökull, the locality enjoys its own microclimate, which at times can be considerably better than the rest of Iceland. The vegetation of the park is quite varied, with birch and rowan woodland scattering its mountain slopes, and the favorable climate allows the birch trees of the Bæjarstaðaskógur Forest to grow taller than in most other places in the country.

Harebell, Yellow Saxifrage and Pyramidal Saxifrage, the most characteristic plants of East Iceland, are common in Skaftafell. Saxifrages, mosses and lichens have been forming pioneer colonies of vegetation, which have rapidly gaining ground since grazing was prohibited within the national park boundary. Today species such as Wild Angelica, Sea Pea and Arctic River Beauty, which are hardly ever seen on pasture land, are common throughout the park.

Insect life in Skaftafell is much more varied than in other parts of the country, and in mid-summer, large numbers of butterflies, especially the species Perizoma blandiata, can be seen there. Midges, an Icelandic delicacy, are also in abundance, which will become painfully obvious to anyone who spends a summer’s night there. There is considerable bird life in the wooded slopes, the Redwing, Common Snipe, Meadow Pipit, and Wren being the most common species. Skeiðarársandur is also one of the most important breeding areas for the Great Skua in the North Atlantic. Large animals are few in Iceland, and the only wild mammals that live in the park are Foxes and Field Mice.

One of the most stunning locations in the area is the glacial lagoon Jökulsárlón, some 32 km east along Route 1 ring road. The lagoon is quite a new feature of the landscape; it started developing in the 1920s, however since 1950 the glacier’s rate of retreat has hastened considerably and lake has grown continually ever since. Today the glacier Breiðamerkurjökull terminates in the northern part of the lake, and ice that breaks from it forms icebergs that spread across its waters. Herring, capelin, salmon, and probably other species of fishes enter the lagoon via a sea outlet called Jökulsá, and the harbour seals follow the food. Eider ducks swim between the icebergs and on the outwash plain around the lagoon, great skuas, arctic skuas, arctic terns, ringed plovers, and other avifauna nest.

Jökulsárlón (Photo by Brian Jenkins)

Jökulsárlón (Photo by Brian Jenkins)Mountains

The Skaftafell National Park is home to some of Iceland’s most impressive mountains, including, the country's highest Hvanndalshnúkur. Basically there are three types of mountain in the park: extinct volcanoes, dormant volcanoes and active volcanoes. If you don’t like volcanoes you’re visiting the wrong country, and will have realized this fairly soon after leaving the airport.

An interactive map of Skaftafell, hover your mouse over the peaks for info or a link to the SummitPost Mountain/Rock page

Hvanndalshnúkur is a peak on the northwestern rim of the Öræfajökull volcano and, as was mentioned earlier, is the highest mountain in Iceland. Until recently the height of the mountain was thought to be 2119m, however it was officially re-measured in August 2005, which established its height at a slightly lower 2,109.6 m. Although the mountain is not technicaly difficult, to reach its summit requieres a considerable amount of glacier traverse over an ice-cap that is heavily crevassed. Most people choose to ascend the mountain as part of a guided party, and guides can be hired at the parks visitors centre and at the parks official campstite. Over the summer period, weather permitting, parties set out for the summit every day, and according to Brian Jenkins excellent Hvanndalshnúkur mountain page, they have a success rate of around 85%.

Kristínartindar (1126m) is one of Skaftafell’s most prominent mountains, and is also probably its most climbed. It’s located neatly between the Skaftafellsjökull and Morsárjökull glaciers, its slopes gorged and steeped by thousands of years of moving ice. The mountain is a relatively easy climb achievable by most fit hikers, and one that’s well worth the effort. The summit is a narrow ridge with vertical drops and each side and, on a clear day offers amazing views of the National Park and beyond.

Skaftafellsjöll is a range of mountains that nestles between the piedmont style glacier of Skeidarárjökull in the east and the Vatnajökull ice-sheet in the north. The range’s mountains include Miðfellstindur (1430m), Þumall (1279m) and Blátindur (1177m), and are visited much less frequently than Skaftafell’s other mountains. Since a footbridge was built crossing the river Morsá the mountains have become much more accessible, although most visitors only walk along the foot of their slopes while hiking to and from Morsárjökull.

The area’s least accessible mountains are the sub glacial summits and the nunataks that protrude from Vatnajökull in the northern regions of the park. The largest of these is Bárðarbunga (2009m), which is located on the parks far northern boundary (unfortunately not shown on the map above). A little further south are two other significant mountains: Hàabunga, which is completely covered by ice and reaches an altitude of 1742 m; and the volcano Grimsvötn which has two nunatak summits on its caldera rim, one reaching 1713 m, the other 1701 m. Due to their remote nature these peaks are very rarely visited, although Grimsvötn makes its presence known with the occasional eruption, and usually require a support team to reach them.

Geology

To put it crudely, Iceland is a geologist's wet dream. With volcanoes, rift-valleys, glaciers, vast alluvial plains and stunning mountain formations all packed onto one island, there are few places on earth that can boast such wide variety of geological features in such a small area. In this section I shall attempt to generally summarise the geological occurrences that eventually gave birth to the Skaftafell and Öræfi areas, however in doing so risk losing sight of some of the subtleties that make the landscape so special. For a more detailed and complete description of Iceland’s geology and geological history, I recommend that you pursue a little further reading; I guarantee your appreciation of the landscape will be enhanced as a result. My personal recommendation is the Geology of Iceland: Rocks and Landscape by Þorlefur Einarsson which is available over the internet or in most good Icelandic book and gift shops (the Icelandic are rightfully proud of their geological heritage). Don’t be put off by the books technical nature, its first half is a little heavy going for the layman, for the really interesting stuff skip to the last few chapters, these deal with the geology in more general terms. Anyway on with the chapter…

Tertiary Period (65-1.64 million years)

n geological terms Iceland is brand spanking new, only coming into existence some 60 million years ago. It is almost entirely composed of lava flows and eruptive hyaloclastites, intersected by widespread, thin sediment beds. Igneous intrusions are also common in the older geological formations. Intensive volcanism has caused the rapid piling up of beds, which continues to this day. Although the weathering and erosion of these beds is extremely active, the rapid nature of accumulation has meant that the volcanic structures are yet to be worn down.

The geological formations of Iceland are divided into four main groups according to stratigraphical age and differ greatly from one another. The oldest is the Tertiary Basalt Formation which was formed in the late Tertiary era (Tertiary Period; 65-1.64 million years ago), next is the Grey Basalt Formation which was formed in the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene, and after that the Móberg Formation which formed in the late Pleistocene. These three formations form the bedrock of the country. The fourth formation is the youngest formation and consists of unconsolidated and poorly formed beds such as till, glaciofluvial deposits, marine, and fluvial sediments, soil and volcanic tephra and lava flows. This last formation was formed towards the end of the Pleistocene and in the Holocene.

The country owes its existence to its location on the spot where asthenosperic flow under the North-East Atlantic plate boundary interacts and mixes with a deep-seated mantle plume. The buoyancy of the Iceland plume leads to dynamic uplift of the Iceland plateau, and high volcanic productivity over the plume produces a thick crust. The Greenland-Færöy Ridge represents the Iceland plume track through the history of the North-East Atlantic. The current plume stem has been imaged seismically down to about 400 km depth, throughout the transition zone and more tentatively down to the core-mantle boundary. Currently, the plume channel reaches the lithosphere under the Vatnajökull Glacier, about 200 km southeast of the plate boundary defined by the Reykjanes and Kolbeinsey Ridges. During the last 20 Ma the Icelandic rift zones have migrated stepwise eastwards to keep their positions near the surface expression of the plume, leading to a complicated and changing pattern of rift zones and transform fault zones.

The youngest formations of bedrock are therefore generally located along a central band, which runs from the Raufarhön region in the north east to the Mýrdalsjökull refion in the south, and the Þrainsskjaldsrhraun area in the south west. Ocean floor spreading has meant the movement of the older formations towards the east and west, with Skaftafell located on the sothern part of the eastern Tertiary Basalt Formation. It is this rock that forms Kristínartindar and the Skaftafellsjöll mountains. Volcanic activity under Vatnajökull during the Quaternary era (1.64 million years to present) has also lead to the creation of Grey Basalt and Móberg Formations which are particularly visible around the Öræfajökull volcano which remains active to this day.

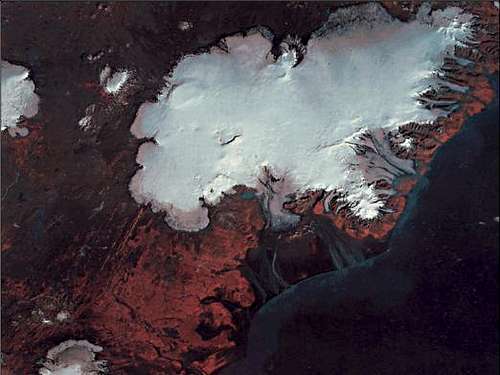

Vatnajökull (Photo by Anders Holm)

Vatnajökull (Photo by Anders Holm)During the Tertiary period the area’s landscape differed considerably from that of today. The land would probably have been quite flat with long crater rows, with shield volcanoes and quite high strato volcanoes dotting the landscape. In the depressions between the many lava flows and in rift valleys, bogs and lakes were widespread, while in the valleys spring fed rivers meandered slowly to the sea. In the red coloured soil that covered almost the entire country warm loving vegetation thrived, but was occasionally overwhelmed and destroyed by sporadic lava flows. Intensive chemical weathering would cause the rapid breakup of the lava surfaces, so that they were soon covered anew by vegetation, which flourished until they were once again intruded on by new lava, and the cycle was repeated.

The land was covered by broad leaved trees including Almus (alder), Betula (birch), Salix (willow), Populus (aspen), Corylus (hazel), Fagus (beech), Acer (maple), Quercus (oak), Ulmus (elm), Liriodendron (tulip-tree), Platanus (plane-tree), Carya (hickory), Castanea (horse chestnut), Ilex (holly), Juglans (walnut), Magnolia (magnolia), Vitis (vine) and Laurus (laurel). To a lesser extent conifers were also present including Pinus (pine), Picea (spruce), Abies (fir), Larix (larch), Taxodium (swamp cypress), Metasequoia (dawn-redwood), andSequoiadendon giganteun (grand sequoia). The Tertiary Icelandic flora appears to be closely related to the present day broadleaf forests of the eastern United States from the south of New York states southwards to the Gulf of New Mexico.

Little is known about the fauna in Iceland. The fossilized remains of insects has been found in lake sediments, and include march flies and aphids (green-fly), related to species living today in south-east Asia and the southern USA respectively. Recently fossilized bone remains of mammals dating from around 2-3.5 million years ago have been found. Although the remains are scarce, they are believed to be from a small member of the deer family.

There is a possibility that during the late Tertiary a land bridge connected Iceland with either Greenland or even via the Iceland-Faeroes Ridge to the British Isles, which at the time was part of continental Europe. Subsidence and the erosion of lava beds has since meant the severing of this link.

The climate during the period was warm and fairly humid, and the presence of index species such as walnut and holly suggests that the mean temperature of the coldest month was above freezing point. Precipitation appears to have been considerable. This combined with the warm climate was conducive to the intensive chemical weathering that broke down much of the areas contemporary lava flows. As stated earlier, the vegetation at the time was very similar to that of present-day eastern USA, from this we can conclude that the climate in Iceland was very similar.

Quaternary Period (1.64 million years to present)

During the Quaternary period the world’s climate underwent a dramatic change in regime, with stadial (glacial) alternating with interstadial (interglacial) conditions. Under stadial conditions much of Iceland was covered by ice sheets, with nunataks, particularly in the north of the country, remaining ice free. During interstadial periods lava flows formed which were quite similar to those of the Tertiary, but in stadial periods the lava accumulation was quite different and Móberg hyaloclastite volcanic structures were built up by subglacial eruptions. The red sediments, which are typical of the Tertiary Basalt Formation, disappeared and were replaced by glacial tillites and yellow or brown hardened silt and sandstones. The fossil record indicates that radical vegetational changes occurred immediately at the start of the Pleistocene (1.65ma to 10,000ya). The warm loving plants of the Tertiary became extinct and did not return, Iceland of course being an island.

All traces of glaciation which can be seen on the present land surface date from the last glacial stage, known in Iceland as the Weichselian, which began 70,000 or 120,000 years ago and ended some 10,000 years ago. During this period almost the entire country was covered by ice. Ice sheets covered the greater part of the country and ice flowed in all directions from the ice divide in the south central highlands, of which the present day Skaftafell was a part. At its maximum the Icelandic ice sheet exceeded 1,500m in thickness and in places its limits stretched as much as 130km from the present shoreline.

Around 18,000 years ago the worlds climate became milder and the colossal ice sheets that had encroached on much of the Icelandic region began to retreat. While the ice sheet was retreating at the end of the glaciation, there were localized, short lived, minor ice centers and divides in the mountainous areas at the edge of the ice sheet. Ice flow from these areas has resulted in an irregular distribution of end moraines and in places striae which cut across older systems of striae. Good examples of this can be found throughout the Skaftafell and Öræfi.

By around 12,000 years ago the ice sheet had retreated to within the present day coastline. Around this time climatic conditions once again became suddenly colder, and once again the ice sheet grew and the glaciers advanced. Around 10,000 years ago the climate warmed rapidly, and the ice retreated quickly, with the Tugnàröræfi region (where the ice had been thickest) completely ice free by 8,000 years ago.

Sea level varied greatly during the Pleistocene, both as a result of eustatic (global) and relative (local) factors. At the maximum of the last stadial period the eustatic sea level was about 100 to 150m lower than that of today, much of the water being bound up by glaciers. During this time the Icelandic Ice sheet, like all large masses of ice, exerted enormous pressure on the crust beneath it forcing it to depress, thus relative sea level was somewhat higher than this estimate. For much of the Late Glacial (12,000 – 10,000 years ago) sea level rise exceeded the crusts ability to rebound following the removal of ice, and much of the coastal shelf and lowlands became flooded. Relative sea level varies throughout the country as different pieces of crust responded at different rates, but generally it was between 60 and 30 m above that of today. Examples of this former coastline can be seen along the drive from Reykjavik to Skaftafell with fossil sea cliffs clearly distinguishable, even though the present shoreline is several miles away to the south. A beautiful example can be seen at Skógar where the waterfall Skógarfoss descends 67m down a former sea cliff onto what is now a lush and fertile coastal plane. It is likely that the southern hills of Skaftafell were also once sea cliffs, which would have been separated by the park’s glaciers flowing into the sea.

By 8,000 years ago isostatic (crustal) uplift had become very rapid and overtaken the rate of eustatic sea level rise. In the Skaftafell region this meant that relative sea level was around 15 m below that of present day levels. Sea levels didn’t reach levels similar to the present days until around 3,000 years ago, after the fast majority of Pleistocene ice had melted away, the Laurentide (North American) Ice Sheet for example, didn’t completely disappear until around 5,000 years ago.

How Iceland’s current vegetation came to colonise the island has been the subject of considerable debate for many years. Up until the 1940’s it was generally believed that during the last ice age the whole of the country was covered by a massive ice sheet, to the extent that only nunataks appeared above the ice, and all life was completely wiped out (tabularasa theory). According to this theory flora first became established when the ice started to melt away, and soil began to accumulate. This theory has become unpopular, and it is now thought that around half of Iceland’s 450 species of higher plants managed to survive in localised ice-free areas, and then re-colonised the land once the ice had disappeared. It is thought that at least 90 species were introduced by man, and others by a variety means such as ocean currents, wind, birds and even icebergs.

The first species to become widespread were at the end of the Late Glacial and beginning of the Holocene (10,000 years ago) were pioneer communities largely compromising of lichens, mosses, sedges and grasses. By around 9,000 years ago the climate had become very warm and dry, and willow and birch covered much of the island. From 7,000 to 8,000 years ago precipitation increased so that the peat bogs became wetter and the woods were forced onto dryer ground. During this period Sphagnum moss is almost entirely absent indicating that although the climate was wet, it was still very mild. Between 2,500 and 5,000 years ago precipitation decreased and the birch forests reclaimed the land taken from them by the peat bogs. During this period, the climate in Iceland was better than at any other point during the Holocene. Temperatures were probably 2-3°C higher than at present, the summers warmer, and the winters shorter and milder. Vegetation covered around ¾ of the country and the treeline reached at least 600m and covered much of Skaftafell’s lower slopes. Glaciers were virtually non-existent with ice confined to only the highest tops, such as Eyjafjallajökull, Snæfell, Öræfajökull and the Vatnajökull summits.

The Holocene’s warm period, known as the Climatic Optimim , ended around 2,500 years ago, when temperatures suddenly fell and percipitation once again increased. Since then climate has been either similar to that of today or, as was up untill the end of the 19th century, worse. The bogs once again spread into the wetter areas and the largely birch forests once again retreated. The large ice caps, such as Vatnajökull, which now domianate the landscape began to form, and gradually increased in size, reaching their maximim at the end of the 19th century. By the time the first settelers aricved in the 9th century, the landscape has changed considerably. Gone were the sweeping birch forests that had once covered the land in a rolling sea of greenery, mostly replaced by bog, mire and grassland type vegetation. Settlement took off in the early 10th century and within the space of some 60 years was more or less complete. The most fertile land was covered by the remaining woodland, and the settlers soon set about clearing them. The best timber was used for building houses, while much of the rest was used to make utensils, tools weapons etc or was burnt as charcoal. Intrensive grazing exentuated the problem, and the bare treeless country that we see today was created. At present only 1% of the country is covered by woodland and shrubs.

History

Apart from the numerous volcanic eruptions that occasionally afflicted the area, and on one occasion caused its complete abandonment (see above), essentially not a lot happened of historical significance in Skaftafell, at least not in terms of culture or politics, and is best described with reference to Iceland as a whole. The settlement of Iceland is a somewhat contentious issue and it is unclear whether or not the Vikings were the first people happen across the island. The Íslendingabók of Ari Thorgilsson claims that the Norse settlers encountered Irish monks when they first arrived, however there is no actual evidence to support this. In any case the first people to arrive in, and eventually settle in Skaftafell were probably Norse so I’ll skip over discussing the Irish, or anyone else who is thought to have lived on the Ireland, and start at 860 AD with the arrival of the Norse.

An engraving from the book Description de l'univers by the French geographer Alain Manesson Mallet (1683)

According to the Landnámbók the first Norseman to rest his feet on Icelandic soil was a Viking by the name of Naddoddr, who stayed for only a short time, but gave the country a name: Snæland (Land of Snow). He was followed by the Swede Garðar Svavarsson, who was the first man to stay over the winter. His stay occurred by accident when, at some time around 860 A.D, a storm pushed his ship far to the north until he reached the eastern coast of Iceland. He landed on a beach just to the east of Öræfajökull, where he stopped for a short while before sailing first westward along the coast, and then north, completing the first circumnavigation of the island. He departed the following summer, never to return, but not before giving the island a new name: Garðarshólmur (literally, Garðar's Island). The second Norseman to winter in Iceland was named Flóki Vilgerðarson, but the precise year of his arrival is not clear. Unfortunately a harsh winter caused all of Flóki's cattle to die, and he cursed this cold country, and when he spotted a drift ice in the fjord he decided to name it Ísland (Iceland). Despite difficulties in finding food, he and his men stayed another year, this time in Borgarfjörður, but they finally headed back to Norway the following summer. Flóki would return much later and settle in what is now known as Flókadalur. The first Norseman to establish a permanent settlement would be Ingólfur Arnarson, had instigated a blood feud in his homeland, Norway. He and his foster-brother Hjörleifur first went on an exploratory expedition to Iceland, and stayed over winter in what is now Álftafjörður. A few years later, they returned to settle the land with their men. When they approached the island, Ingólfur cast his high seat pillars overboard and swore that he would settle where they drifted to shore. He then sent his slaves Vífill and Karli to search for the pillars, Ingólfur's slaves found the pillars by Arnarhvol, and when summer came, he built a farmstead that would eventually become Reykjavík.

Ingólfur arrival is significant as it marks the beginning of the Age of Settlement in Iceland. Within 60 years all the productive land had been taken, the Landnámbók mentions as many as 1,500 farmsteads and names more than 3,500 people. It is estimated that during the Age of Settlement some 15,000 to 20,000 people made Iceland their home.

Skaftafell became on of the original farms occupying a fertile plain, enriched by the tephra from Öræfajökull. During the Middle Ages in became a large manor farm and local assembly site. The church acquired the farm quite early on in the period and it remained in ecclesiastical hands for many years. In 1271 after a long and exhausting civil war, Iceland had become a part of the Kingdom of Norway, and later on in 1397 when Norway joined Denmark in the Kalmar Union, the island became part of Denmark. The Reformation was introduced in Denmark in 1536 and no small incentive for independence from Rome involved seizure of Church lands by the King. In 1551 Christian III brought about the Reformation of the Church in Iceland, which resulted in Danish control over its property, and the confiscation of its great wealth. Skaftafell thus fell into the hands of the Danish king, and became a royal estate. The farm was located at a spot called Gömlutún (which means Old Hay Field), at the foot of the hills just to the west of the present campsite, where its ruins can still be seen today. Between the years 1830 and 1850 the tephra and glacial outwash of Skeiðarásandur encroached on the farmland, covering the fields in sand. The farm was forced to relocate 100m higher up the mountainside where it remained until 1964 when the Icelandic government acquired the land and designated the area as a national park.

For those with an interest in the history of the area there is an old farmhouse located inside the park just to the north of the campsite that is open to visitors. Sel consists of a couple of small timber buildings, attached side by side and with traditional turf roofs. Although the interiors are quite bare, housing only a few old pieces of furniture and farm tools, the site is well worth a visit, particularly as it is always open, and as an added bonus, free.

Climate

There is a saying in Iceland that goes something like “If you don’t like the weather right now, wait another five minutes”, this might give you an idea of what the climate is like there. It is quite possible for one to experience all four seasons over the space of one day, sunny and mild temperatures; windy, cool temperatures and rain; snow and temperatures below zero degrees C. When this happens, which to be fair it rarely does, it is an expression of Iceland’s location on the transitional border between Arctic and temperate seas, and between the cold air masses of the Arctic and the warm air masses of lower latitudes.

Being an island, Iceland experiences a maritime climate. The country is located at 63-67°N and 18-23°W, but like much of Europe has considerably milder climate than its location northerly location might imply. This is thanks to a branch of the Gulf Stream, known as the Irminger Current, that flows along the southern and the islands western coast greatly moderating the climate. In the north the cold East Greenland Current flows west of Iceland, but a branch of that current, the East Icelandic Current, approaches Iceland’s northeast and eastern coasts. This is reflected in the variability of coastal sea surface temperatures around Iceland. During the coldest months (January-March) they are generally close to +2°C. Sea temperatures rise to over +10°C in the south and west coasts during the summer, slightly over +8°C in the north, but are coolest at the east coast where summer sea temperatures remain below +8°C.

Annual mean temperatures along the coasts of southern and southwestern Iceland reach 4-6°C, but are lower in other parts of the island. The average temperature of the warmest month, July, exceeds 10°C in the southern and western lowlands, but is below that in other parts of the country. This means that the larger part of Iceland belongs to the arctic climate zone. The warmest summer days around Iceland can reach 20-25°C, with the absolutely highest temperatures recorded at around +30°C.

Winters in Iceland, are generally very mild for its northerly latitude. The coastal lowlands have mean January temperatures close to 0°C, and only in the central highlands do temperatures stay below -10°C. The lowest winter temperatures are found in the north and in the highlands, and are generally in the range -25 to -30°C, with the lowest temperature ever recorded reaching -39.7°C.

Vatnajökull (Photo by Vid Pogachnik)

Vatnajökull (Photo by Vid Pogachnik)The dominant wind directions are from easterly directions, E, NE-SE, and reflect the passage of atmospheric low-pressure cyclones on paths just south of Iceland. Westerly and northwesterly winds are infrequent. The pattern of precipitation reflects this passage of cyclones, which exposes the south coast, particularly the Öræfi region, to heavy precipitation.

Regionally and locally both wind directions and wind speeds are highly influenced by local topography and altitude. Generally, wind speeds are higher in the highlands than the coastal lowlands, but local topography can canalize winds and cause very high winds in some lowland valleys. The frequency of storms is highest during the autumn and winter months. Storm days per year, with average wind speeds exceeding 18 m/second, are generally 10-20 in the lowlands, but at places >50 in the highlands and at exposed outer coastal areas. The large ice caps, Vatnajökull in particular, can generate strong catabatic winds.

An interesting affect of Iceland’s numerous large areas of un-vegetated land is its dust storms. Strong (>15-20 m/second), dry winds coming off the interior or the large ice caps and onto the large proglacial sandur areas and the arid highlands can generate quite large, heavy dust storms. In the Skaftafell area this can be quiet common, from winds blowing over Skeiðarársandur in the west. The dust storms are very effective in eroding and transporting soil materials, and it has been calculated that more than 10 tons of material can be in motion across every transect meter per hour. In the arid highlands north of the Vatnajökull ice cap, where vegetation cover is sparse and the soils heavily affected by volcanic tephra fallouts, dust storms are very frequent in the summer and early autumn.

Thunderstorms are very rare in Iceland, but do occasionally (less than 5 days per year) occur in the southern part of the country in late summertime when warm air is deflected to northern latitudes from warm air masses over Europe. Thunderstorms can also occur in connection with deep lows approaching from the southwest in winter, when cold air is drawn off Canada and warms rapidly over the ocean, forming thunderclouds. Usually, lightning is observed in connection with ash plumes from volcanic eruptions.

So when visiting Iceland and the Skaftafell National Park, expect fairly good weather, but prepare for spells of bad weather. Summers are generally fairly mild and calm, but occasionally a deep low-pressure cyclone can bring in with buckets of rain and heavy storms. As with any mountain region weather in the highlands can be very unstable and unpredictable, so be sure to pack sunglasses and T-shirts, as well as raingear, warm clothing and windbreakers and all other equipment essential to your expedition… but you already knew that right?

A more focused section on the area’s mountain weather is posted just down the page… here!

Mountain Fun

There’s plenty to be done here, from easy valley hikes to truly technical alpine routes to ski mountaineering. Guiding services and weather forecasts are available from the park’s visitor’s center, and the official acts as a good base camp for mountain expeditions.

The following information is provided by Haraldur Guðmundsson at www.edinburghjmcs.org.uk

Hiking and Scrambling

Most visitors to the park won’t climb the higher mountains but will be there for the hiking. The Skaftafellsheiði region of the park is very popular and has numerous paths and trails that cross its plateau and ascend the slopes of Kristinartindar. The area is exceptionally attractive, home to one of Icelands few mature forests, and offers panoramic views of the park and coastal plain. The waterfall Svartifoss is located in on the southern part of the area, and is a top spot for a photograph.

The most popular hiking summit is Kristinartindar, which is reached via Skaftafellsheiði. The paths are pretty good and there’s some rather nice exposure to be had on the upper reaches of the mountain. The only downside is its popularity, but don’t let this put you off, it’s still much quieter than the most popular mountains in Europe or the USA.

For anyone who wants to get away from the crowds there is a trail that does a circuit of the Morsárdalur and Kjós valleys, visiting the terminus of Morsárjökull. Although the route doesn’t take you up any mountains it’s a pretty good option if the weather poor and the option of climbing to a summit unapealing, or just a bad idea.

Mountaineering

The history of mountaineering in Iceland is not a long one, and it was not until the 1930s that people wandered off to the hills with any purposes other than sheep gathering. Until then, mountaineers were not considered anything more than peculiar individuals with an unhealthy desire for discomfort. Around 1940 a group of enthusiastic hikers and mountaineers formed a club, organising trips and building huts and bothies. Unfortunately this club became inactive around 1955 and interest in mountaineering slackened. It wasn’t until 1977, that climbers who had experienced the Alps realized the importance of the role of the Alpine/Mountaineering clubs, and sat down and founded the Icelandic Alpine Club. Since then it has been the backbone of the rapid development of the Icelandic climbing scene.

In 1985 the mountaineers of Iceland had their eyes opened to the possible alpine routes available to them thanks to a visit from the British mountaineer Doug Scott. He and three local climbers did a route called Scotts-leið, which Scott graded as TD+, so far unrepeated. After his visit a couple of routes were established in the Skaftafell and Öræfi areas. These routes are ~1500m and most are graded TD+ or harder.

Rock Climbing

The quality of the rock is in Iceland is generally quite poor; so do not expect anything near British, American or European standards. However, there are five crags which climbers visit during the summer months. The season ranges from mid May to mid September, and the best time to go climbing is in mid July. Iceland uses the American Yosemite grading system and all the routes are graded according to this system. The largest climbing area in the country is Hnappavellir and is located just 20km east of Skaftafell. The rocks, which are old sea cliffs, vary between 10-25m in height and were discovered accidentally in 1990. At present there are some 90 bolted routes, all single pitch, and are graded from 5.5 to 5.13d. The number of routes explored to date has probably reached 100, many of high quality.

If visiting the crags be aware that the area belongs to the people at Hnappavellir who have kindly allowed climbers to climb there and is closed to the general public. Take good care of the area, only camp in the marked camping area, and use the toilet provided.

Ice climbing

Ice climbing is made favorable in Iceland thanks to the porous rock and the variable temperatures that tease the freezing point. The combination of the groundwater’s easy access out of the rock and the temperature swings, often creates soft and very enjoyable ice to climb. In Iceland the climbs are mostly pure waterfalls; however the number of mixed routes is increase year by year, a great deal of these are in the Skaftafell region.

The climbing season stretches from mid October through mid May, with the most reliable period falling between December and March.

Though local climbers may complain if there has been a thaw for a couple of weeks, there is always ice – you may just have to climb higher up the mountain to get to the best ice. In Skaftafell there is always the glacier ice.

The grading system was originally borrowed from the Scottish winter grades (Roman numerals), but has now evolved into a unique system in its own right. The grades are called “P”-grades, named after Páll Sveinsson, one of Iceland’s most influential climbers over the last 25 years. Prefixing the P began as a joke, as Páll used to stretch the Scottish grades until there was little that connected them to the Scottish winter grades. For comparison, P4 is roughly Scottish Grade V (5+). Some younger climbers have started using Jeff Lowe’s American grades AI and WI, for the sake of easier comparisons with foreign climbs. The M-grade has been used for the mixed climbs.

Every year the Icelandic Alpine club holds an ice climbing festival during a weekend in the latter part of February. All the best Icelandic ice climbers can be seen in action over this weekend and the festival is usually held somewhere far away from Reykjavík. If you’re planning to visit the country to ice climb, this would be a good weekend to do it. There are many unclimbed routes, especially away from the Reykjavík area. If you think you have climbed a new route, send the information to info@outdoors.is. You should include the name of the route, its grade, a detailed description of it and accurate location. We will file this information and also get it publish in the annual Icelandic Alpine Club journal.

Just next door to Skaftafell is the Öræfasveit ice climbing region, which contains the most varied choice of ice climbing routes in Iceland. The region actually consists of a number of smaller areas located very close to one another. It’s not long since ice climbing began in Öræfasveit and only a fraction of the routes have been climbed. Einar Sigurðsson, a local mountain guide in Öræfi, has done most of the exploration in the area, and has also completed the majority of the first ascents. With difficulties ranging from the easiest grades up to P5 and M6, and this is also the main alpine venue, Einar has the best information about unclimbed lines – and there are a couple of good ones just waiting to be nabbed, so interested climbers should contact him.

To obtain inforamtion regarding the ice conditions contact From Coast To Mountains Travel mountain guides.

Off-piste Mountain Skiing

Ten years ago everyone in Iceland used mountain skis, today telemark is the thing to know, and in recent years snowboarding has also gained popularity. The best time of year for skiing off-piste is from mid-February to June.

Owing to the height of the region’s mountains Skaftafell offers some of the best skiing in Iceland. On Öræfajökull you can ski down a slope of 2000m (6500 ft) from top to bottom. Luckily this is Iceland and there are no trees to worry about, all you have to do is just down and go, providing there’s enough snow of course. In many places it’s possible to drive up to the snow line or higher in specially equipped jeeps, they’re pretty expensive to higher though. There are many great skiing opportunities on the glaciers, although because of crevasses such trips can be dangerous. Those with little experience of crevasse navigation and rescue should avoid such areas. If possible it’s always better to persuade someone who knows the glacier to come along with you and guides can be hired at Parks visitors centre.

Hard wind-packed snow or firn is common, and powder snow, unfortunately, is much less common, of course, there’s a lot of seasonal change, and good snow conditions do occur. Because of the packed snow, it is usually easy to accent the mountains by using skins under your skis. The weather tends to be a lot more stable in the later part of the skiing season and as a rule of thumb, before Easter it’s wise only to ski on the smaller mountains closer to settlements, and after Easter is the time to travel further afield and ski the larger mountains such as those in Skaftafell. Pay heed to the weather forecast if you’re planning to ski. It is often a good idea to choose two mountains some distance from each other and then let the weather decide which you go for. The trick with this is not to let the forecast decide until the day before at the earliest. If you’re going on the weekend, be flexible about which day you go and let the forecast determine it.

Avalanches are a real hazard in the mountains in Iceland and it’s recommended that you take and know how to use an avalanche beeper. A light shovel should always be kept close at hand and of course you should have a map, compass and GPS reciever.

In the National Park, Virkisjökull, an outlet glacier that flows between Svínafell and Sandfell, is one of two most popular routes to Hvannadalshnúkur. The route is varied and the view is superb. To do this route you need some experience in glacier travelling. If you’re unsure, think about taking a guide along. It’s also possible to ski down Virkisjökull between March and May, although you can walk the route in June and sometimes July when it is becoming risky to ski.

Ski Touring

The glaciers and highlands in Iceland offer endless fantastic opportunities for both long and short skiing trips. These areas intrigue and excite everyone who travel on them, which is why cross-country skiing is so popular in Iceland. The season generally lasts from March to July. In the early part of the season the lower areas tend to be better, with the glaciers becoming more popular later in the season.

A good map, compass and GPS are all an absolute necessity for travelling on glaciers and in the highlands, but remember the instruments themselves are not enough; skill and experience should never be underestimated. The best maps to use are those with a dense grid, specially prepared for use with GPS instruments.

Snowdrifts are very common so campers should be wary of placing tents in depressions that look prone to excessive accumulation, and it can take no time at all for a tent to be covered by a drift. It’s common practice to build a snow wall a short distance from the tent to help protect it from the strong, gusty winds. Alternativly there are many huts in the highlands, and for winter or spring trips, it’s recommended that you plan your route so that you can spend the night in one of these huts. If something does go wrong, it’s good to know that the next hut is only a short distance away.

Some companies offer guided cross-country skiing trips including Icelandic Mountain Guides, From Coast To Mountains Travel, Ferðafélag Íslands and Útivist.

Practical Information

Mountain Conditions

An up-to-date weather forcast can be obtained by calling (+354) 902 0600 which provides an answearing machine service for the Icelandic Meteorological Office. An online English forcast can be found at: www.vedur.is/english/.

If mountaineers and climbers have to call for assistance, it’s frequently as a result of the weather. Although the following table is not scientifically produced, it does give some idea of the worst to expect. If you’re planning a trip lasting several days in an area where you cannot reach shelter, you must be prepared to deal with these conditions:

If mountaineers and climbers have to call for assistance, it’s frequently as a result of the weather. Although the following table is not scientifically produced, it does give some idea of the worst to expect. If you’re planning a trip lasting several days in an area where you cannot reach shelter, you must be prepared to deal with these conditions:

| Summer travel | Winter travel | |

|---|---|---|

| Lowlands | 2 ºC (35 ºF), 15 m/s (30 mph) winds, rain or sleet | -10 ºC (15 ºF), 25 m/s (56 mph) winds, snow |

| Highlands | -2 ºC (35 ºF), 20 m/s (45 mph) winds, sleet or snow | -15 ºC (5 ºF), 35 m/s (78 mph) winds, snow |

| High mountains and glaciers | -10 ºC (15 ºF), 25 m/s (56 mph) winds, snow | -20 ºC (-4 ºF), 45 m/s (100 mph) winds, snow |

When packing, bare in mind that although the temperatures are not unbearably cold, the wind chill factor tends to make up for it. Lots of precipitation, strong winds and temperatures of around 0°C (32 °F) can be a dangerous combination for the unprepared mountaineer. Even well designed, waterproof clothing can leave you unprotected, and you will quickly become cold if you stop.

Snow avalanches are common in the winter, although you don’t have to worry about them in the summer. The strong winds cause the snow to move around a lot, so avalanche beepers, snow shovels and knowledge of how to use them are all essential for the winter traveller.

Mountain Rescue

There’s no need to obtain permission or any special insurance for mountaineering in Iceland. As yet, nobody has been charged for being rescued, although every so often it is talked about, although if you’re planning a potentially risky trip, it would be wise to be aware of insurance procedures there.

The emergency number in Iceland is 112. In Iceland, GSM mobile phones (900MHz) only work in populated areas or by the main roads, NMT-450 (Nordic automatic Mobile Telephone system) mobile phones offer much better coverage , and can be rented from The Icelandic Mountain Guides and Ultima Thule. It is also possible to rent satellite phones for the Irridium system from Siminn.

The Icelandic Coast Guard takes care of all serious air and sea rescues. Often bad weather conditions prevents helicopter flights, when this happens the police and/or the Mountain rescue teams are called out, depending on whether the incident has occurred in the lowlands or the highlands.

The rescue teams are groups of volunteers trained in rescue techniques, and the time it takes for them to reach the scene of an incident depends on the situation and the conditions. In general, the teams do their job incredibly well, especially since the members are not paid professionals. The rescue team association, provides information for travellers and can be reached on (+354) 561 7111.

Getting There

Skaftafell is around 330km west of Reykjavík, wich is a drive of around 4-5 hours; and is around 1 hour from the nea Höfn í Hornafjorður the nearest town. The Road 1, the main ring road that circles the entire country passes along the southern boundary of the Park, and is the only road that goes anywhere near the area. There are no roads in the National Park except for the tracks leading up to the farms. Parking space is available near the campsite, and trails through the national park start at the visitor center. Visitors are free to go anywhere in the national park but are advised to follow the marked trails. The Nordic Adventure Travel Company and Flybus, who run buses all over Iceland, offer a number of services to the National Park, although they can be infrequent and are non-existent in winter.

Be aware that all the highland roads are closed to ordinary cars in the winter and spring. Some companies offer tours in specially adapted jeeps that can be driven on snow and the service is becoming increasingly popular with skiiers, using the service to get close to the trailhead if their trek is in one of the more remote areas. For those who have not tried it before, these jeep tours are also great fun.

Atlantsflug runs aircraft flights in south-east Iceland from their own private airport located at "Skaftafell National Airport" located just to the south of the prak boundary. They offer flights to various locations around the Vatnajökull Glacier and into the highlands of Iceland, to locations like Landmannalaugar, Langisjór, Laki and Lakagigar. All their standard tours are listed on their website, and all other requests are on a quotation basis.

Please note that there is no towns or villages in Öræfi. There are only farms, and the only shop open all year round is the Shell filling station in Freysnes; so make sure that you have enough supplies for your trip before you travel, because if you get cut short it’s a long drive to the nearest supermarket. In summer there is a small coffee shop, which sells some supplies, open at the National Parks Visitors Centre and at the glacial lagoon Jökulsárlón.

Red Tape

There are a few considerations and restrictions that must be adhered to when visiting or camping in the National Park. Campers must avoid making noise on the campsite between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 7.00 a.m. The vegetation on the campsite must be cared for at all times, and don’t pour hot water on the ground or scorch vegetation with cooking equipment. Damage to vegetation, such as breaking branches or uprooting plants, is prohibited, as is disturbing animal life, tampering with basalt and other geological formations or building cairns. Littering and burying rubbish is also prohibited in the National Park, obviously.

Camping and Accommodation

The Park Authorities provide an official campsite with separate areas for tents and motor caravans. All visitors are allowed to put up tents or sleep in caravans and cars for a reasonable fee. Camping or sleeping in vehicles outside the campsite is prohibited without special permission from the park superintendent. The only problem with the official campsite is that the drainage is very poor, and when it rains, which it does a lot in Iceland, it tends to get very waterlogged.

A good alternative to the official campsite is the Svínafell Campsite, located just to the east of the Park, which is on a slight slope and has no problem with drainage. The only problem here is that it’s a little exposed to the wind, however if you have a good, sturdy tent then this shouldn’t bother you. The campsite has excellent cooking and shower facilities, and if that doesn’t grab you it also has its own heated outdoor swimming pool and hot tubs. If camping isn’t your thing or the weather is so atrocious that camping just isn’t an option, the site also has 6 small cabins each able to accommodate 4 persons, as well as a bunkhouse that has space for 8 people.

The area also has limited hotel and guesthouse accommodation at Hotel Skaftafell, located 5km east of the Park, the Frost and Fire Guest House in Höfn, and the Litla Hof Guesthouse around 20km to the east, near Höfn.

A Brief Guide to Icelandic

I would guess that most people who read this article will not be from Iceland, so for their benefit I though a short section on the Icelandic language might be helpful. Icelandic is directly related to Old Norse and people with knowledge of a Scandinavian language will therefore have a head start. For the rest of us the language might seem intimidating with words containing extra unfamiliar letter, words that appear to be no more than a random collection of vowels, and worst of all both. This guide is unluckily to have you speaking and pronouncing Icelandic words with a happy fluidity, however it might help with guesswork, especially when attempting to find your way around the country.

Firstly it would help to have some knowledge of the building block of the language, its alphabet. The letters C (se), Q (kú) and W (tvöfalt vaff) are also used but only in foreign loanwords. The letter Z (seta) is no longer used in Icelandic, except in the newspaper Morgunblaðið.

| A a | Á á | B b | D d | Ð ð | E e | É é | F f | G g | H h | I i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Í í | J j | K k | L l | M m | N n | O o | Ó ó | P p | R r | S s |

| T t | U u | Ú ú | V v | X x | Y y | Ý ý | Þ þ | Æ æ | Ö ö | |

As you can see there are two unfamiliar letters here. The first is Ð/ð, pronounced as a hard th, as in then (e.g. Skeiðarásandur). The second Þ/þ (often replaced by the in guidebooks), is pronounced as a soft, aspirated the, as in thistle (e.g. Þingvellir). There are also numerous other differences in pronunciation between the English and Icelandic alphabets. The letter j is pronounced as a y (e.g. jökulhlaps). When f is found before an i or n it is pronounced as a p (e.g. Hafnarfjörður). The letter h takes on a k-sound when in front of an l or n (e.g. Hlemmur). When r is before l or n it takes on an extra d sound (e.g. Perlan). The double ll sound rather like the Welsh equivalent, a soft kl sound made somewhere in the back of the mouth (e.g. Hengill). If you can’t quite get your head around all of this, then it might come as a relief to know that English is spoken widely throughout Iceland, however a few words of Icelandic will go a long way in helping break down barriers.

The following table contains some useful phrases that you’ll now hopefully be able to pronounce.

| English | Íslenska (Icelandic) |

|---|---|

| Hello | Halló, Góðan dag(inn) Sæll (>m) Sæl (>f) |

| Welcome | Velkomin(n) |

| How are you? | Hvað segir þú? Hvernig hefur þú það? |

| I'm fine. | Allt gott, Allt fínt, Allt ágætt ,Bara fínt |

| What's your name? | Hvað heitir þú? |

| My name is ... | Ég heiti ... |

| Where are you from? | Hvaðan ertu? Hvaðan kemur þú? |

| I'm from ... | Ég er frá ... |

| Pleased to meet you | Gaman að kynnast þér / Gaman að hitta þig |

| Good morning | Góðan daginn |

| Good afternoon | Góðan dag |

| Good evening | Góða kvöldið |

| Good night | Góða nótt |

| Goodbye | Vertu blessaður (masculine) Vertu blessuð (femenine) Bless á meðan, Bless bless (informal) |

| See you later | Við sjáumst, Sjáumst síðar |

| Good luck! | Gangi þér vel! |

| Cheers! | Skál! |

| Have a nice day | Hafðu það gott |

| I don't understand | Ég skil það ekki |

| Please say that again | Gætirðu sagt þetta aftur? Gætirðu endurtekið þetta? |

| Please speak more slowly | Gætirðu talað hægar? Viltu tala svolítið hægar? |

| Do you speak Icelandic? | Talar þú íslensku? |

| Yes, a little | Já, smávegis |

| Excuse me | Afsakið! Fyrirgefðu! |

| Sorry | Því miður / Fyrirgefðu / Mér þykir það leitt (I'm sorry) |

| Thank you | takk, takk fyrir þakka þér fyrir, kærar þakkir |

| You're welcome | það var ekkert |

| Where's the toilet? | Hvar er klósettið? |

| Will you dance with me? | Viltu dansa við mig? |

| I love you | Ég elska þig |

| How do you say ... in Icelandic? | Hvernig segir maður ... á íslensku? |

| Leave me alone! | Láttu mig í friði! |

| Help! | Hjálp! |

| Call the police! | Náið í lögregluna! |

Maps

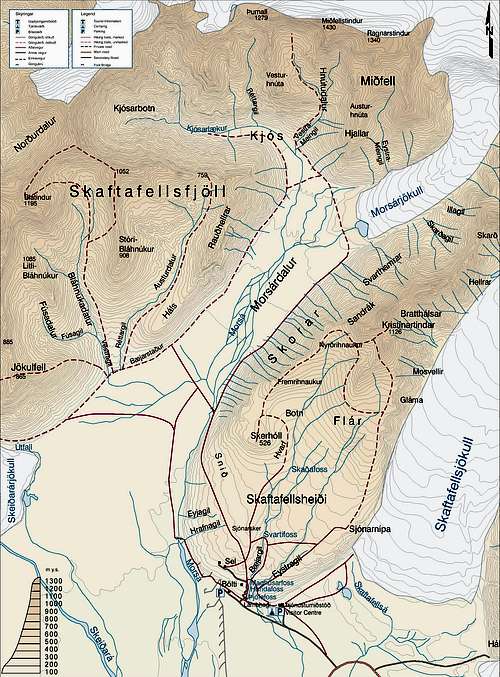

One thing to bear in mind when buying maps in Iceland, is that they aren’t that good. The map of Skaftafell is no exception although it is slightly better than several of the other maps in its series. The map of Skaftafell comes in the form of a double sided sheet, one with a map to the scale of 1:100,000, the other with a map of 1:25,000. Ironically the 1:100,000 map proves to be the better of the two, and although the scale isn’t great for mountain navigation, and there is a complete absence of gridlines, the actual survey itself is quite good, although it suffers from being a little out of date (1986). The 1:25,000 map is truly dreadful, suffering from all the problems, bar scale, of the 1:100,000 map. The main problem with it is that the cartography has been simplified to such a level that the map bears little resemblance to what is on the ground. Contour lines have been straightened and rounded, paths and trails are represented as straight lines, and worst of all there is a complete absence of rock features, a fact that can make something that is quite challenging in reality look like a walk in the park when viewed on paper. Of course there’s not much you can do about this as there are no other maps to choose from, so it’s best just to buy the map but while using it, be very aware of its failings.

Navigation

1:100 000 and 1:25 000 Skaftafell

Road

Ferðakort 2 - 1:250 000 - Vesturland og Suðurland

Ferðakort 3 - 1:250 000 - Norðaustur- og Austurland

Guidebooks

Scandinavian Europe Travel Guide

External Links

General

www.iceland.org - website for the Icelandic Foreign Service

www.iceland.is - official Icelandic tourist site

www.visiticeland.com - a travel website full of useful information and links

Guiding Services

www.mountainguide.is - Icelandic Mountain Guides

www.hofsnes.com - From Coast To Mountains Travel

www.fi.is - Icelandic guiding company, Ferðafélag Íslands

www.utivist.is - Útivist Mountain Guides

Accommodation

www.simnet.is - Homepage of a neaby campsite

www.hotelskaftafell.is - one of Skaftafell's few hotels

www.frostandfire.is - link to a nearby bunkouse

www.farmholidays.is - link to a B&B in Öræfi

Travel

www.nat.is - bus routes

www.bsi.is - official website of Icelandic bus company BSI

www.atf.is - Atlantsflug internal air travel company

www.icelandair.com/en-gb/ - Book a flight with Iceland Air…

www.airiceland.is - or with Air Iceland

Geology

www.volcano.si.edu - Volcanoes!

www2.norvol.hi.is - official website of the Nordic Volcanological Centre

www.iceland-nh.net - website about Iceland’s natural history

Maps and Guidebooks

www.lmi.is - Iceland’s official mapping company

www.omnimap.com - buy Icelandic Maps!

shop.lonelyplanet.com - buy general travel guides from Lonely Planet

www.newhollandpublishers.com - some general travel guides from Globetrotter

Icelandic

www.ismal.hi.is - Íslensk málstöð (Icelandic Language Institute)

www.icelandic.hi.is - The University of Iceland's Free Course in Modern Icelandic Language and Culture

www.mentalcode.com - online Icelandic study guide featuring interactive exercises for vocabulary and grammar

www.samkoma.com - Icelandic Grammar Notebook

www.hafronska.org - Háfrónska málhreyfingin (High Icelandic language movement) - an organisation that promotes the 'High Icelandic language' (háfrónska), an ultrapurist form of Modern Icelandic

www.hugtakasafn.utn.stjr.is - online Icelandic dictionary

and finally...

It's not big, it's not clever, but it made me smile... sorry.