Part 0 - Cycling and Scrambling from Calgary to Vancouver

In A Nutshell

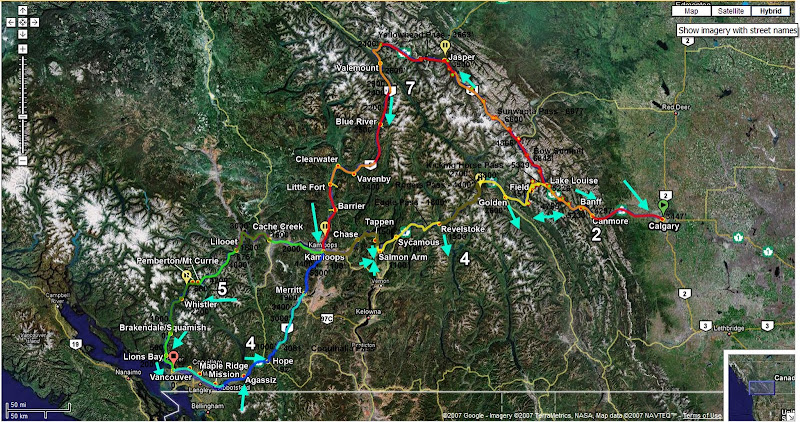

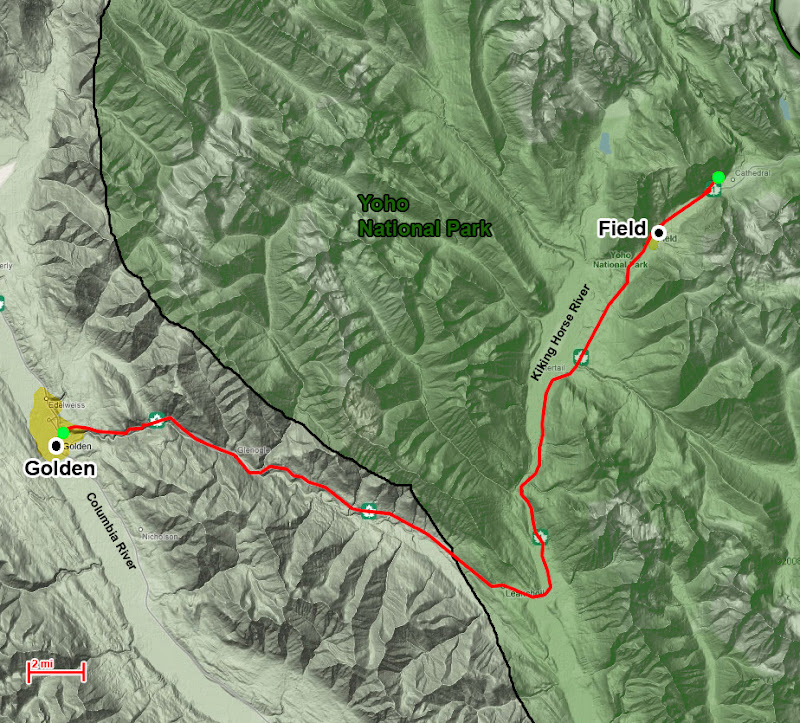

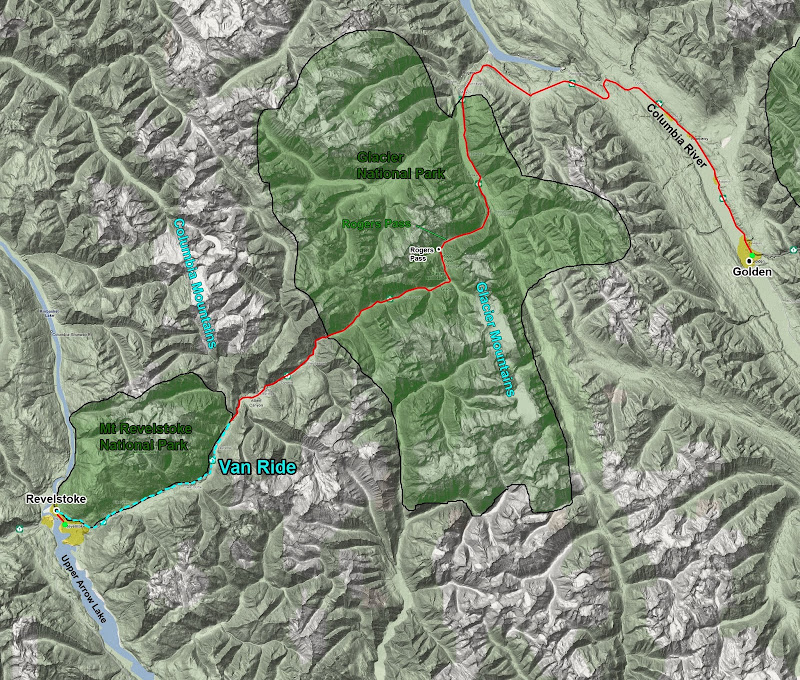

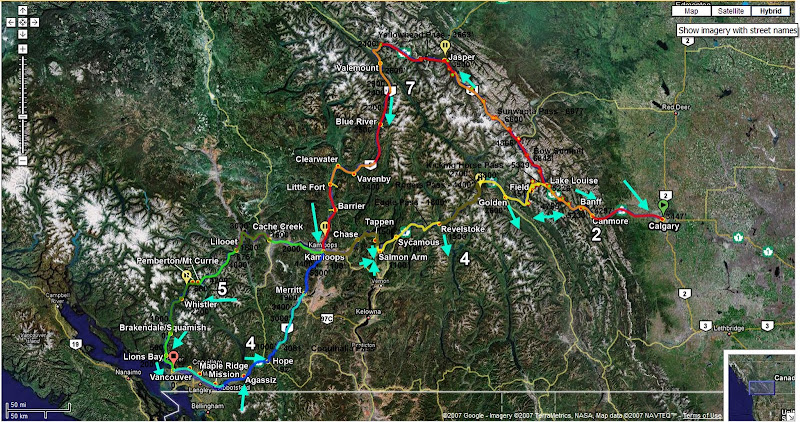

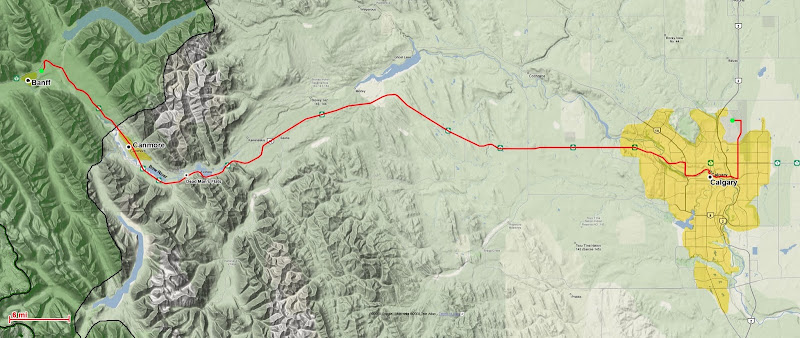

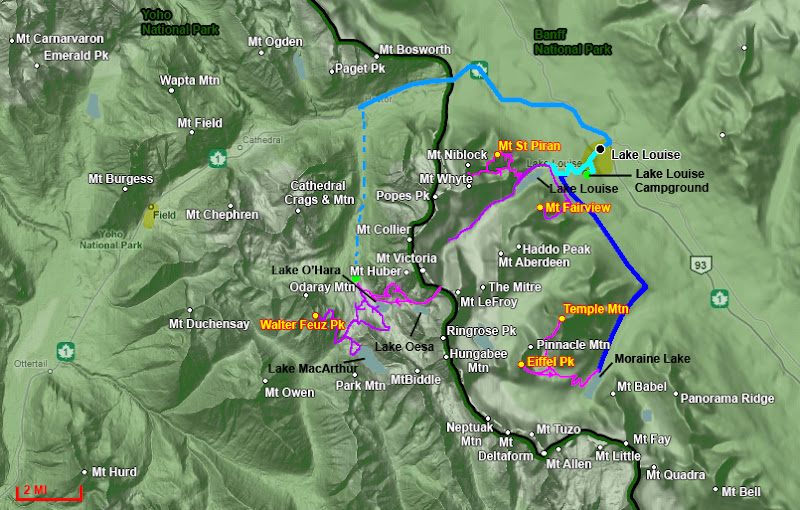

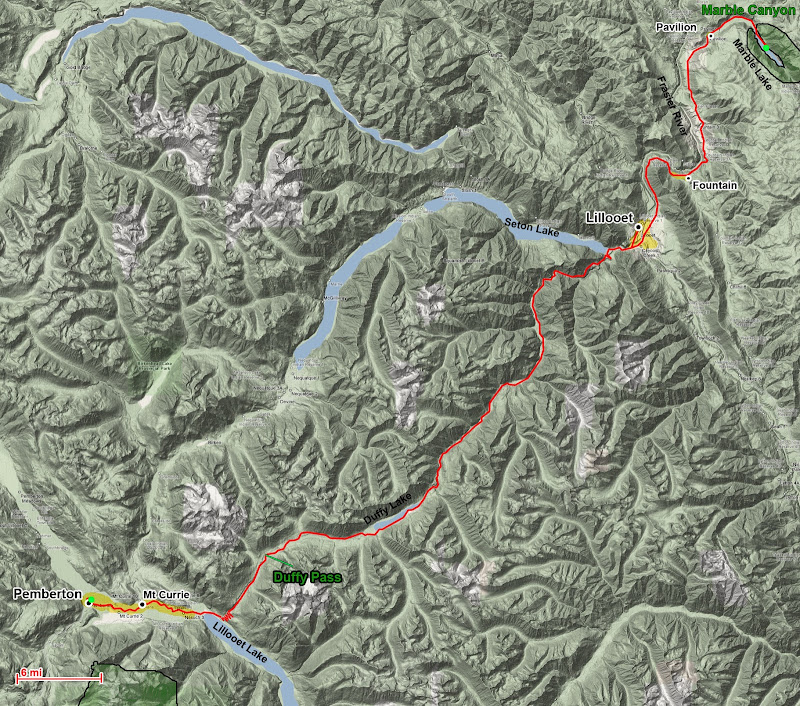

A rough map of the trip

A rough map of the trip

This trip report is very long, partly because it was a very long trip (23 days), partly because I covered a lot of ground (cycled 770 miles and climbed over 10 peaks), and also because I’ve decided not to just write the standard “went there, did that” format. The trip was as much an inward journey for me as an outward one, so I feel that ignoring details relevant to my motivations and self-reflection would miss out on a lot of the adventure.

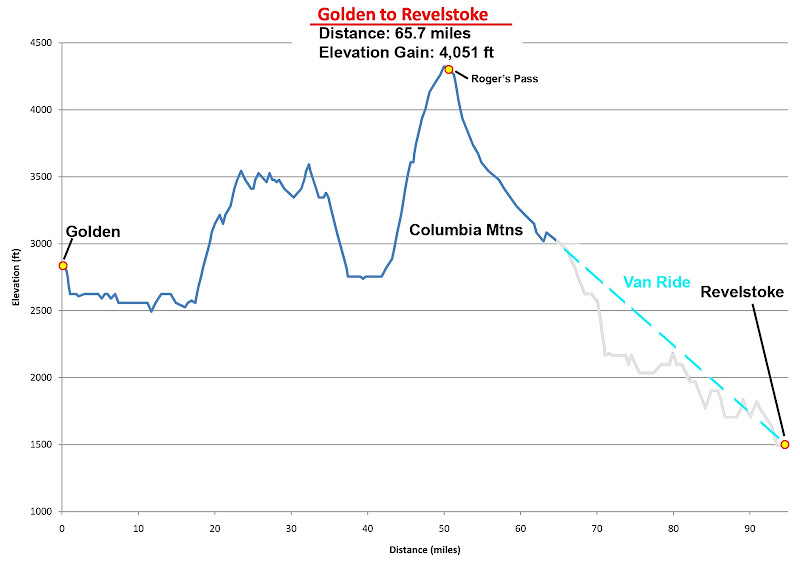

In a nutshell, from July 29th to August 17th I cycled solo across Western Canada, from Calgary, Alberta, to Vancouver, British Columbia via Banff, Kamloops, and Whistler. Along the way I hiked and climbed throughout the

Canadian Rockies and a small amount in the Coastal Range, summitting about 10 peaks. I cycled fully self-supported (apart from supply refills along the way) with camping gear and basic scrambling equipment, and this was to be my first ever multi-day cycling tour and first time ever combining cycling with scrambling on an approach. Although it was a very ambitious trip, in the end it was a wild success, and I had many interesting experiences along the way. For those that like stats, here they are:

Cycling (17 days)

- Distance: 767 miles (45 miles / day)

- Elevation Gain: ca. 41,000 ft (2,400 ft/day)

- Elevation Loss: ca. 42,900 ft (2,500 ft/day)

- Average Speed: 12 mph

- Weight Carried: ca. 82 lbs (nearly 90 lbs when maxed out on water capacity)

Hiking/Scrambling (8 days)

- Distance: 82 miles (10 miles/day)

- Elevation Gain: 36,010 ft (4,500 ft/day)

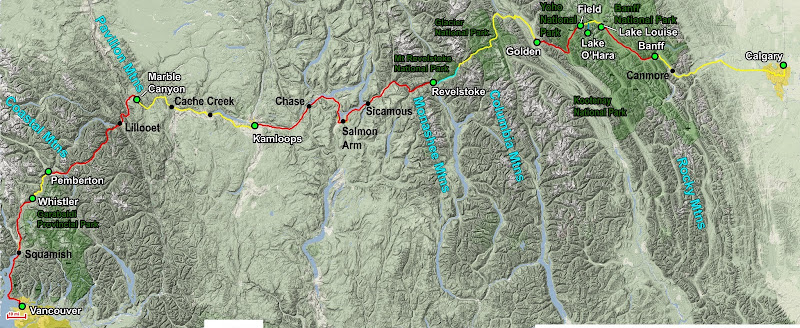

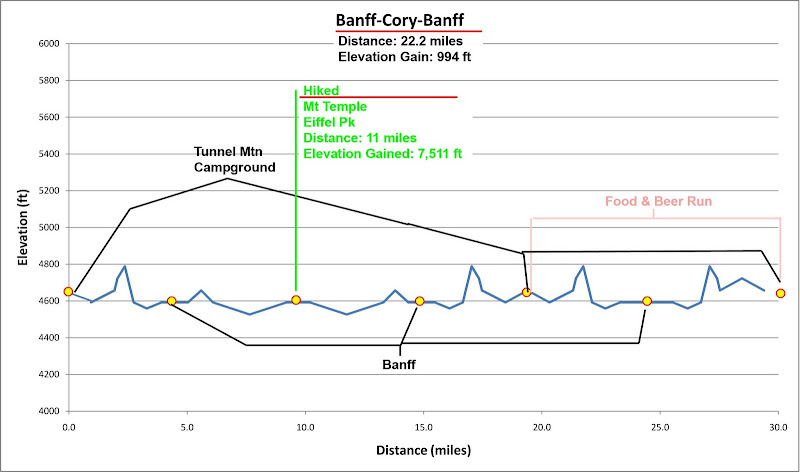

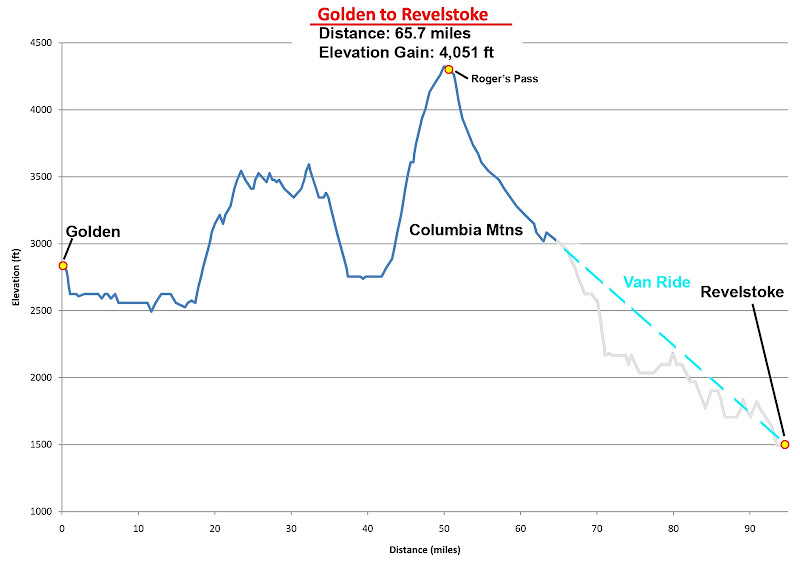

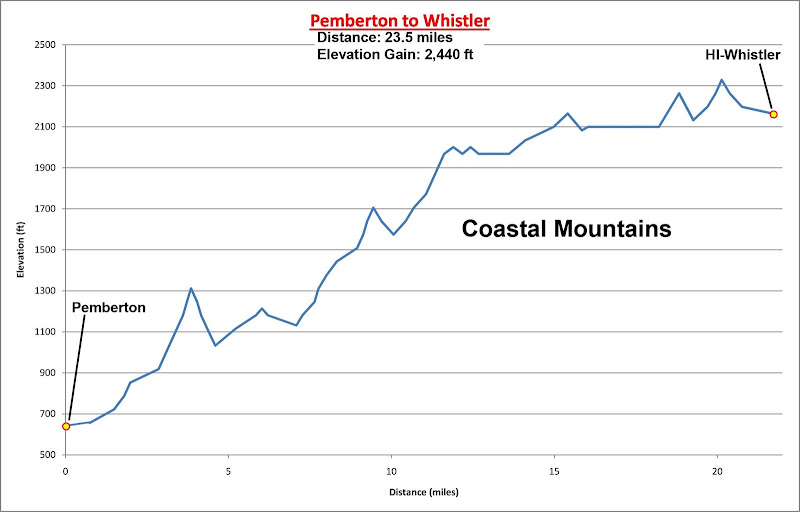

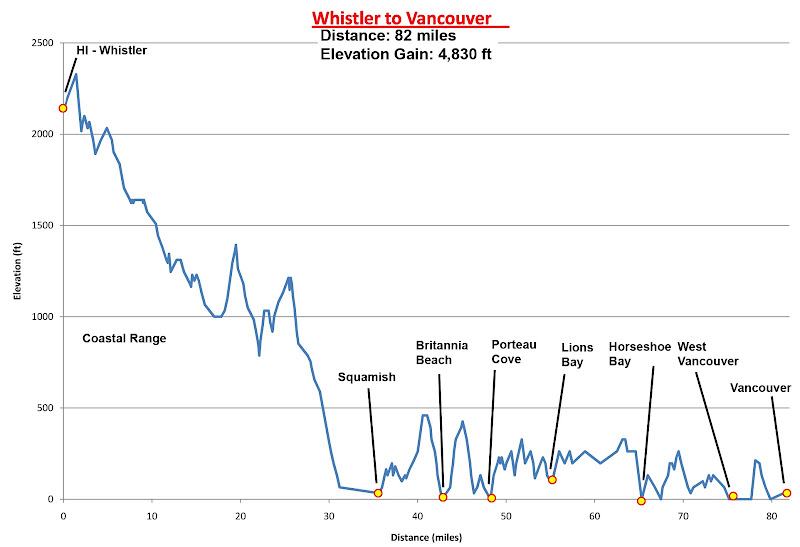

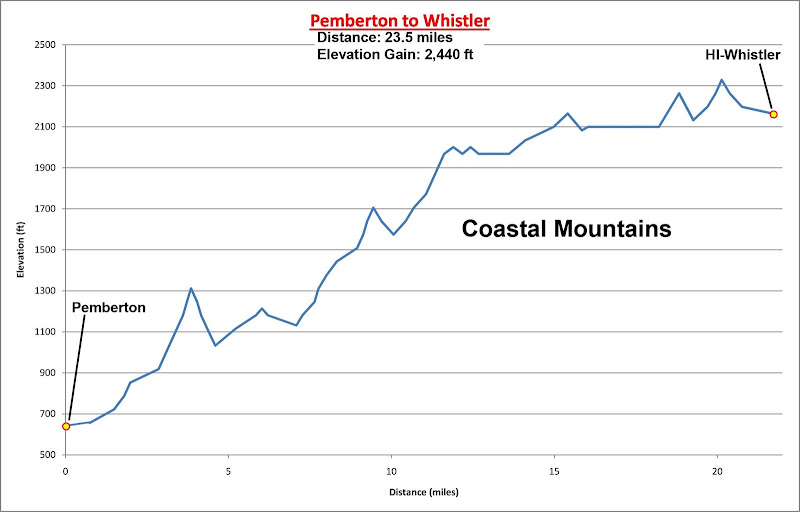

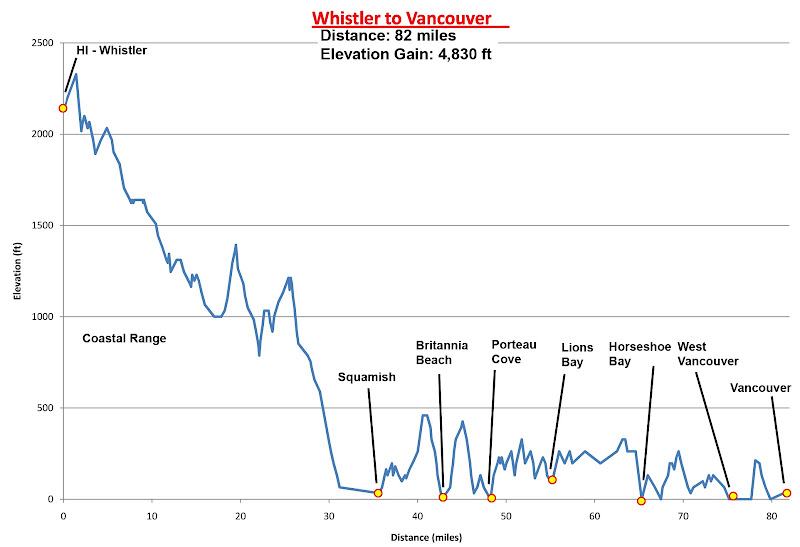

Diagrammed elevation profile of the trip

Diagrammed elevation profile of the trip

The Premise

The summer of 2008 was a pivotal summer for me. I was on the verge of completing my graduate studies in structural engineering, and I had just spent 6 months interning at a prestigious firm in New York City that worked on exactly the sort of projects that I had so ambitiously trained myself for over the past 5 years.

|

| Views from the office |

Although I loved New York City, the Shawagunks and the Adirondacks could barely begin to replace the outdoor lifestyle of the West that has become such a part of me. Despite being a dream job, I had turned down an offer to continue at the firm as a full employee, partly because I was insistent on finishing the optional extended portion of my degree and then contacting them, but also because I couldn’t decide what to do. I have always had a conflicting dichotomy of the love for big cities and the love for wilderness, and as my career track pulled me ever more strongly away from Nature, I have had a greater struggle between which passion to follow.

It was in this state that I began planning some summer excursions, partly with the idea that this might be the last time for many years that I would be able to get out in the mountains and deserts that I so loved. No summer job this year – it was to be my last hurrah before fully entering a full-time career, and I wanted to do a number of big trips that I had been dreaming to do for a while. Or perhaps the trips could help me be at ease with scaling down my career ambitions for the sake of the mountains. For June I would spend the month in Alaska, climbing Denali with a group of climbing friends on a self-led expedition. With this trip already set in stone, I decided to take the month of July “off” to “rest” and recover from Denali and get in good cycling shape for my next big summer objective: cycling across Western Canada.

Cycling has always been very therapeutic for me, both physical and emotional, so I guess part of the idea of this trip was to be a symbolic therapy for my current angst about my future.

The Trip

![Valley of the 6 Glaciers]() Valley of the 6 Glaciers (Banff National Park)

Valley of the 6 Glaciers (Banff National Park)

I first got the idea of doing a cycling trip in the Banff/Jasper area in 1999 when I took a road trip through the area with my father. At the time I was barely getting into climbing peaks, and on the trip we didn’t venture far from the car as I was still recuperating from a major reconstructive knee surgery. The region left a strong impression on me – some details in particular were the great combination of extremely rugged roadside beauty and surprisingly mild road grades through the mountains, perfect conditions for a great cycle touring route. Ever since that trip, I had casually toyed with the idea of someday cycling through there, maybe ambitiously, as a loop from Calgary.

The trip in the early planning stages. working out day divisions and noting prevailing wind directions as I was debating West-to-East vs. East-to-West

The trip in the early planning stages. working out day divisions and noting prevailing wind directions as I was debating West-to-East vs. East-to-West

Over the years as I have fallen in love with mountaineering, one major influence in my interests and ambitions in the mountains has been

Bob Burd and his

Sierra Challenges. Not only did they expand my awareness of what I could accomplish in single-day mega hikes, leading to my idea to day hike Gannett Peak, but in 2006 when I managed to do the full 10 days of the Challenge I learned a lot about multi-day ultra-endurance events and how to go about attempting them.

|

| Vancouver |

From this background, in 2008 when I decided to finally do a cycling tour in Banff, I got really ambitious. First, the trip wouldn’t just be about cycling in the area. I would also hike and scramble up peaks. I was confident that if I paced myself, I could go continuously for many days, and that the effort of doing day hikes in the Canadian Rockies wouldn’t tire me out too much for such a pace. Also, I theorized that hiking days could be “rest” days for my cycling days, and vice-versa, since the activities use slightly different muscles.

Then I just went off the deep end. I had always wanted to see Vancouver and had been learning more about Whistler and the Vancouver area, so I began to get interested in linking up my cycling trip from Calgary all the way to Vancouver. I had the time, so what the hell – if only cycled 50 miles a day, taking all day if I wanted to, I would have time to do this. And so the idea for my uber-ambitious mega-cycling-climbing trip was born.

Partners, Planning, and Preparation

Still, the idea was a little crazy since at the time 50 miles was my all-time cycling record for one day, on an unloaded bike, and it left me wasted for a few days after. Also, I wasn’t about to do this alone just yet. I had never solo-toured before (or done a cycling tour for that matter), and I had done very little soloing in the mountains.

For the partner problem, I knew just who to call – my friend Joel Wilson, who had joined me for the

Gannett Peak day hike sufferfest. He likes these sorts of trips, and he was very interested in the idea. Still, he had research to do that summer, but expected to be able to take at least a week off. So we tentatively planned for him to join me at the very least in the Banff area. This allowed the nice possibility of trying to climb Mt Assiniboine along the way, since we could afford to bring the weight of a rope and light rack on our bikes as Joel wouldn’t need to carry as much gear for the trip and wouldn’t be riding as far with it.

Sadly, in the end Joel couldn’t take enough time off to do the whole trip, and then he got a girlfriend, so I was left friendless for the trip. At this point I was enthusiastic enough about the trip that I decided just to go solo, but Mt Assiniboine would have to wait. And my newly purchased SPOT Personal Locator Beacon could be used to let family know on a regular basis whether I was making progress on my route, so at least someone could call in a rescue if I needed one.

I would fly to Calgary with my bike packed up in a box. Then I would assemble it at the airport and begin my ride. In Vancouver I would get another box to pack up my bike, and ride a Greyhound bus to Seattle to meet some friends and visit a prospective employer before shipping my bike back to Salt Lake City flying back to school in Berkeley via Los Angeles (for further job interviews). Busy month! Plus there was still the possibility of my friends in Seattle driving up to meet me in Whistler with extra climbing gear to tackle Mt Garabaldi.

![Mt Garabaldi]() Mt Garabaldi

Mt Garabaldi

For planning and preparations, I made good use of the month of July staying at home in Salt Lake City. The planning was a major hurdle in and of itself. I had absolutely no idea what I was really getting into, and I couldn’t find any information readily available for doing such a cycling tour, as far as where to stay, quality of roads, suggested routes, distances to be covered each day, where to restock on food and water, etc.

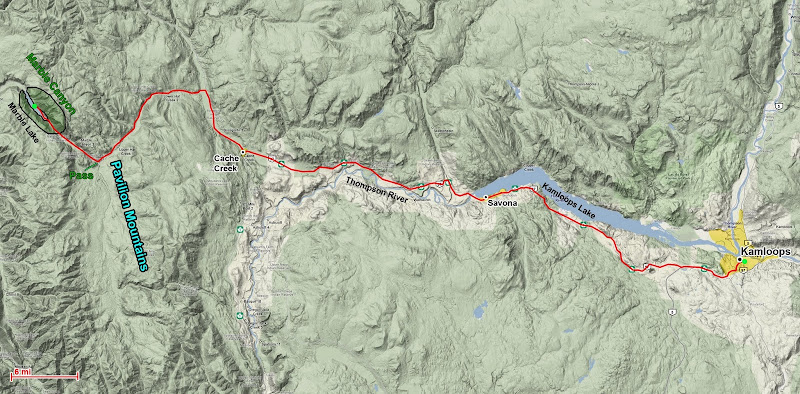

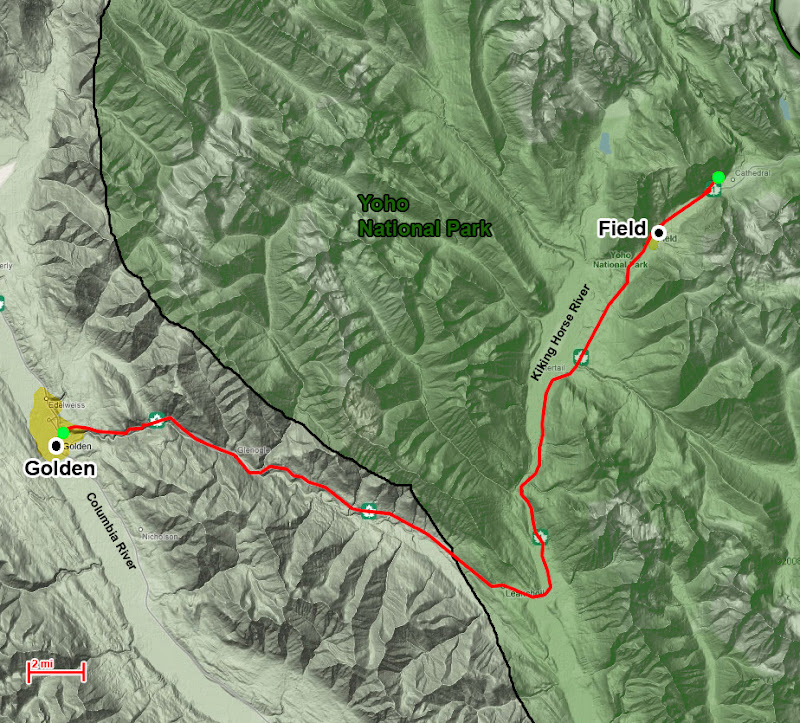

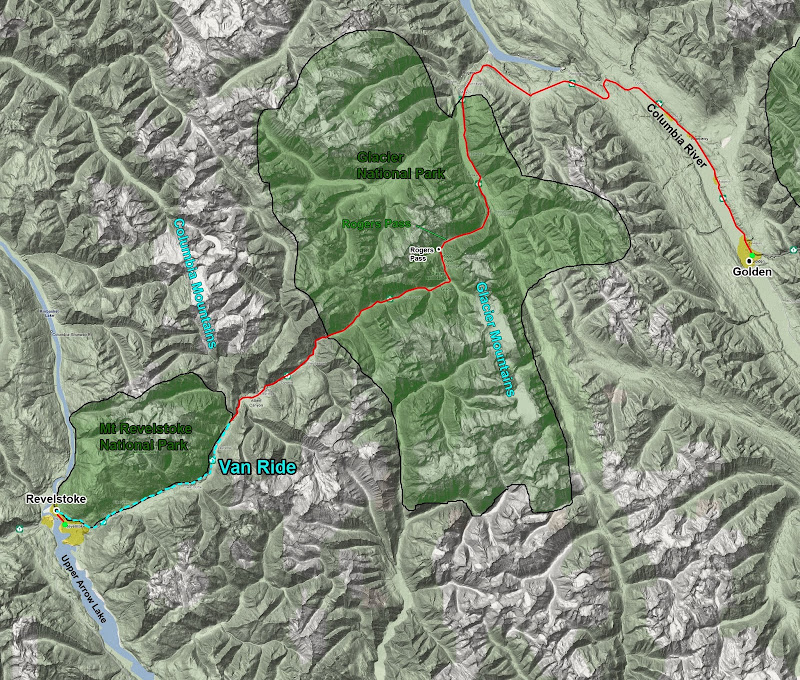

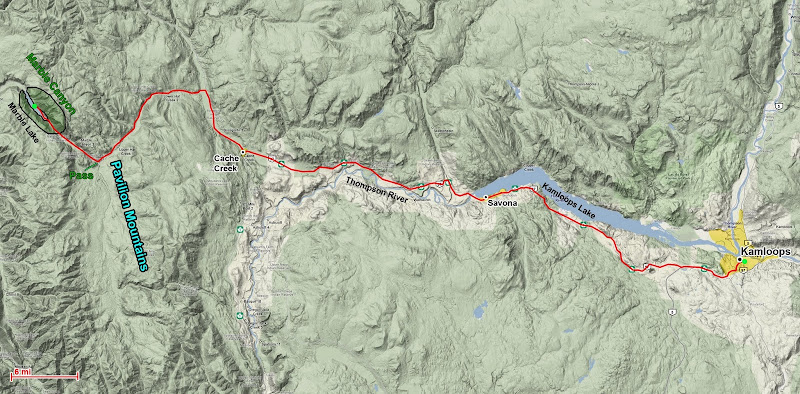

That and I needed to learn how to do a multi-day cycling tour. So I designed a custom trip from scratch based on internet searches, point of personal interest, and the joys of Google Maps and Google Earth. A few variations were planned, all of which passed handily through Kamloops, making a figure-8 centered on the town. I was very tempted with a northern route via Jasper and then down the backside of the Canadian Rockies. But then that was a major detour, and I would miss Yoho National Park, which I had yet to see. So I would take Canada Highway 1 from Calgary to Kamloops.

On the next leg, the more obvious route was to join Highway 5 and take it south and into the river valley that empties into Vancouver. This way is more well-traveled, but from what I read online, the there was a pass that was notorious for cycling tourists for its steepness and elevation gain from either side; plus, the idea of cycling through endless flat land and suburbs to get to Vancouver seemed less appealing to me.

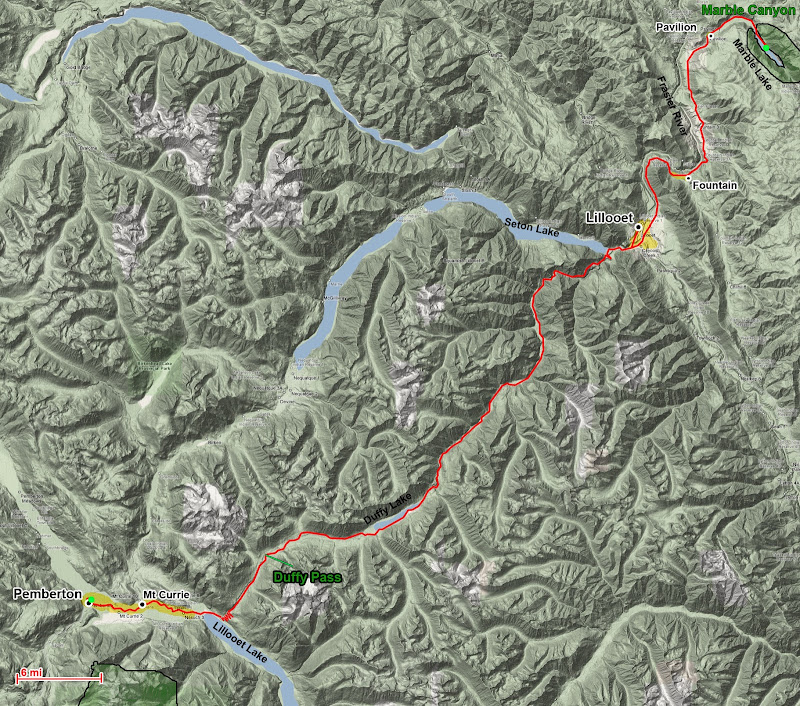

By looking closely at maps, I picked together a northern route that took me to Cache Creek, over the Pavilion Range to Lillooete, and then over the Coastal Range in 2 hurdles, one from Lillooet to Pemberton, and then another main climb from Pemberton to Whistler. From there it was (mostly) downhill to Vancouver on the vividly-named Sea-to-Sky Highway. The idea of descending from the mountains to the ocean, cycling along a highway like California’s Highway 1, sandwiched between the mountains and the sea seemed too great to pass up. Plus, this route brought me in to Vancouver from the north, allowing me to get downtown with a minimum of cycling within the city.

![Howe Sound]() View along the Sea to Sky Highway

View along the Sea to Sky Highway

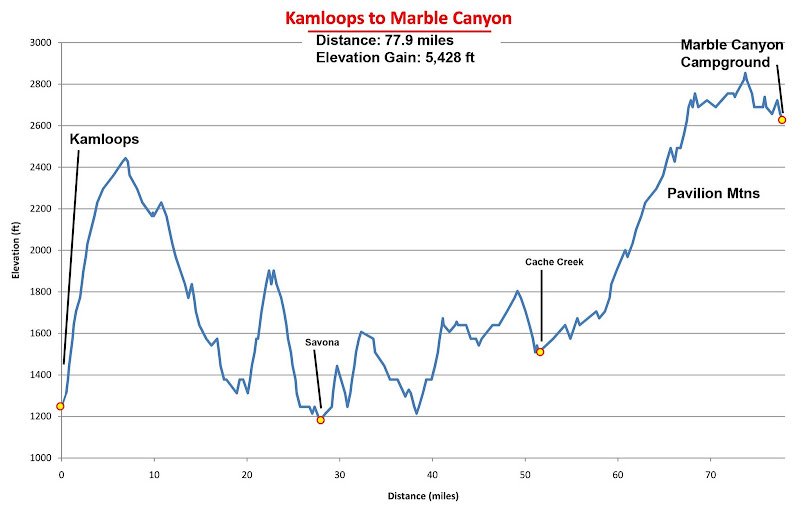

There was a big problem with the alternate route, though. Upon closer inspection, the stretch from Lillooet to Pemberton seemed to fade away. Topographic maps showed a nice valley linking the two towns, but this was filled with a reservoir and I could only find railroad tracks alongside the water. There was a road (that as far as I could tell from satellite photos was paved) that cut across the arc that the valley carved through the mountains, but this shortcut had a significant climb up and over the mountains. In addition to climbing over 3,000 ft in one push, I found the first 1,500 ft to be very steep – grades as steep as 10% and nothing less than 5%. This would not be pretty with a fully loaded touring bike at the end of a major cycling tour. I had no idea if I could even peddle up such a consistently steep grade with so much weight on my bike. Still, the picturesque descent on the Sea-to-Sky Highway ending with a sudden and dramatic entrance into Vancouver (similar to entering San Francisco via the Golden Gate Bridge) seemed too romantic of an idea to pass up. So it was settled.

My dad insisted that I was going backwards on the route, since it was against the prevailing wind, but I was set on having Vancouver as the endpoint. It seemed more rewarding and a much nicer way to end the trip by arriving someplace new. Also, research into typical wind weather data for August in the towns I was riding through showed that the winds were primarily directed by the mountains and not the prevailing current. Regardless which way I traveled, I would have headwind about half the time, tail wind the other half, and some cross-wind here and there.

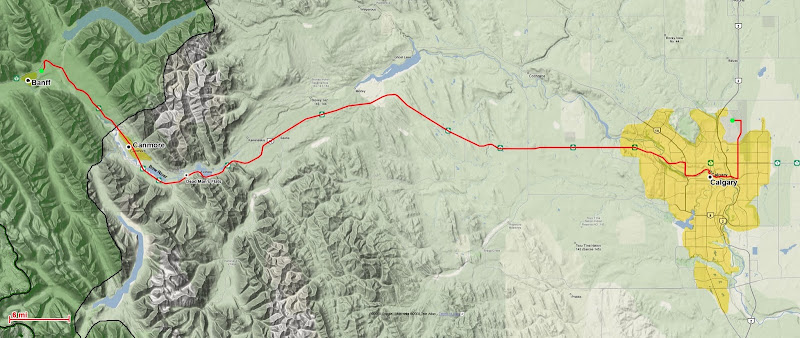

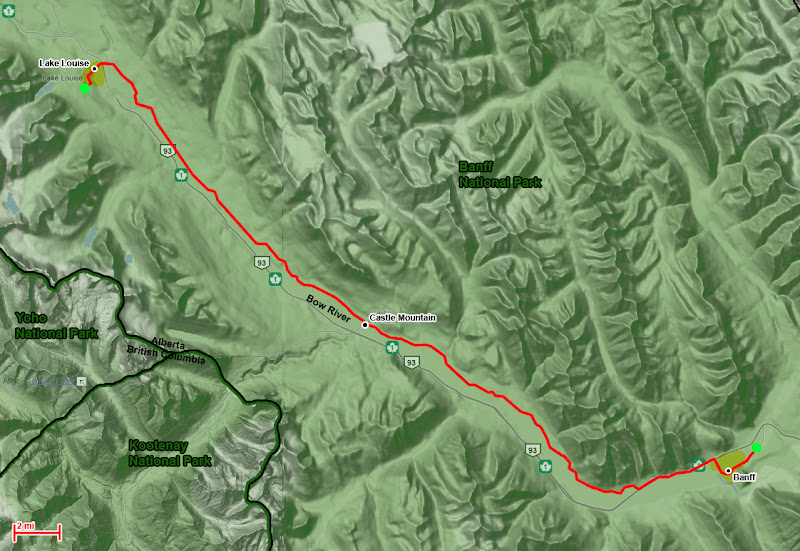

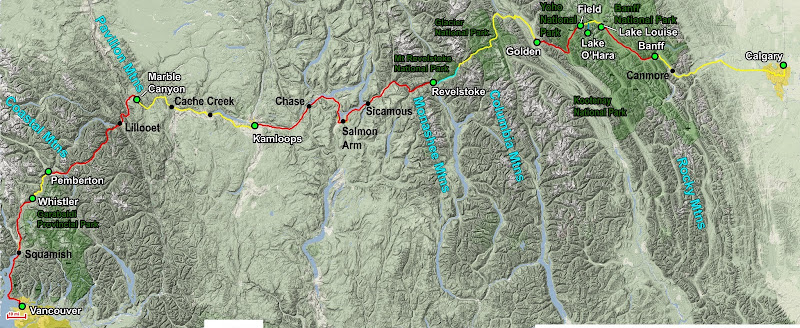

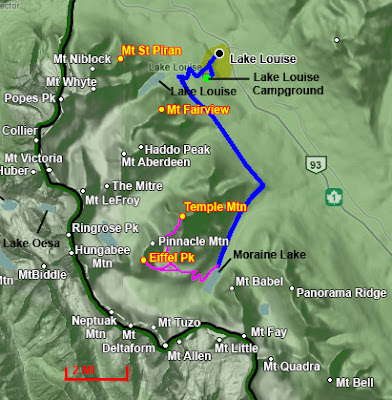

A detailed map of the route (actual, not planned)

A detailed map of the route (actual, not planned)

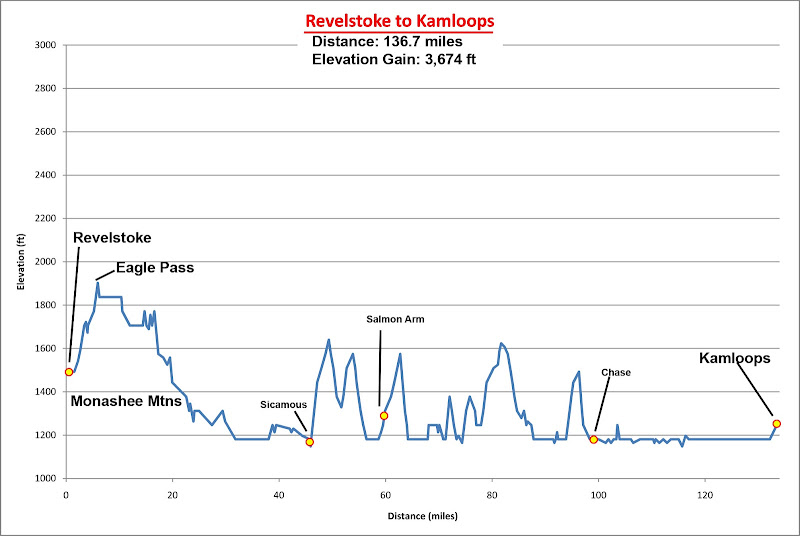

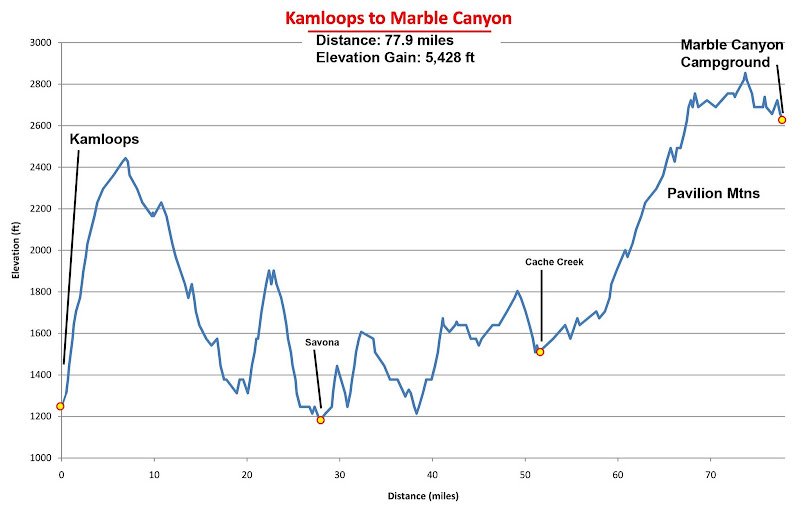

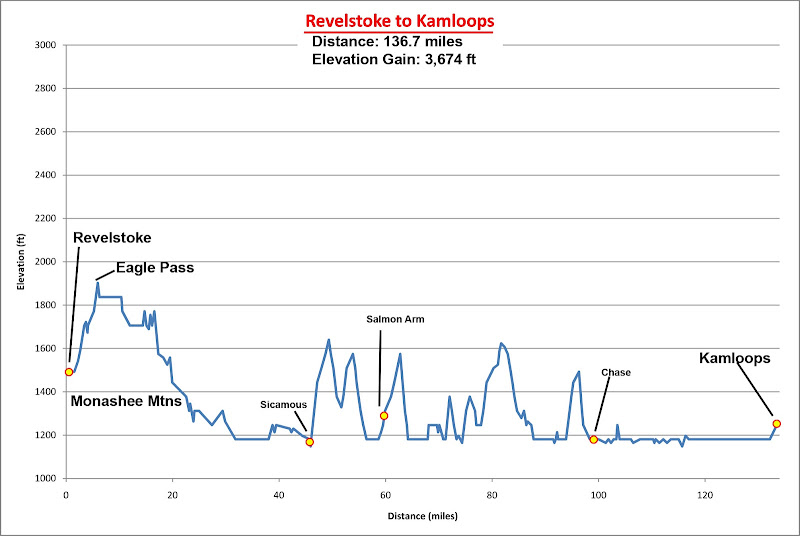

With the route known, I then digitized the route (nerdy, I know, but helpful). Not only could I plan were I should stop based on distance and elevation gain, but I could have a breakdown printed out with me to know how much distance and elevation gain between various points, which proved very helpful in the trip when I had to deviate from my planned stops (which happened a lot!) and I wanted to make informed decisions. Because there were a lot of ways in which I could break up the route, by having the map digitized on a spread sheet, I could intelligently plan stops so that I could start small with elevation gain and distance, and gradually ramp it up.

As far as climbing, I spent hours poring over guidebooks and Google Earth piecing together potential peaks. Eventually I drew up a list of possible outings (more than I could do, but then allowing for a nice variety of options). One logistic to work out was how I would get to the peaks without a car, so finding routes with reasonable cycling approaches was key. I could cycle out from a “base camp”, climb a peak, and then head back. On peaks further out, but along my route, I could cycle over, climb the peak, and continue on to that night’s destination. The second concern was what I would do with the gear and food on my bike, being left unattended in Bear country.

Light camo- netting would protect my bike from theft (after it was stashed in the bushes, plus the netting could make ‘questionable’ roadside camping easier), but were there any bear boxes at the trailheads, or would I have to bring a bear canister? A call to the ranger office in Banff answered that question – no bear boxes, and the Canadians don’t trust bear canisters. My only option would be to hang food. I was also informed that I didn’t need to make campsite reservations as I should be able to find a site coming in on a bicycle and it being a slow year. When the ranger inquired as to my overall plans and I told him, he warned me that the stretch from around Kamloops all the way to the Coastal Range was a desert that could reach 100

o F during August. I had seen the barren areas on satellite photos, but just assumed it was barren and cool highlands – I hadn’t even considered that rain-drenched British Columbia would have a desert! I would have to get across that section of my route fast – and carry a lot of water.

In order to prep myself for the trip while trying to recover from Denali, I tried to cycle at least every other day, if not every day, for the entire month – and when I went out I aimed to punish myself. The emphasis would be hills galore, and as fast as I could take them. Of course I would also make sure my rides were initially at least 20 miles and then gradually increase the distance to 50 miles or so. The 10-mile 2,000 ft climb in Millcreek Canyon got routine and loops from my house in Holladay to Brighton and Alta ski resorts became reasonable outings.

Packing went less straightforward. By the time I had amassed all of the gear I thought I needed, it weighed over 90 lbs. After some thoughtful sorting and inventorying to see where the weight was, I managed to trim it down to 82 lbs – still not a very good number, but it was the best I could do with the unknowns. Spread-sheeting everything, as nerdy as it seemed at the time, was very helpful, since I could make sure the weight was balanced well between my 4 panniers and rear bag. Also, bringing a printout list with me made repacking every day very easy, since everything was packed so tightly and needed to stay balanced throughout the trip.

In the end I decided to go without a trailer (harder to control on down hills, and required more parts to bring for repairs) in favor of front panniers (messes with steering a tad, but otherwise lighter and simpler for airline travel), and going by what apparently is a North American preference of 70% weight on the rear and 30% weight on the front. Also, I chose my mountain bike, outfitted with slicks, over my lighter and faster road bike. The name of the game on this ride would be comfort, and I needed as low of a gear as possible for the ‘death pass’ near Lillooete.

Day 0 - Test Run

Planning and packing took much longer than expected, and my procrastination for actually loading up my bike and riding with it stretched until the day before my flight to Calgary. I planned to load it up exactly as I would ride, including wearing my climbing daypack carrying a full camelback of water, and then cycle from my house to the top of Immigration Canyon and back.This would give me a nice continuous 1,500 ft climb on grades similar to anything I expected to experience on the route except for the ‘death pass’.

The first run didn’t go so well, as it was very difficult controlling the bicycle, with extremely bad fluttering in the rear, especially whenever I turned. Moving weight lower solved this problem, and I was on my way.

Overall the ride was fine once I got used to the sluggish handling and riding slower. I knew I would need to practice self-discipline in focusing on perceived effort and not speed as my pace metric for the trip so that I wouldn’t burn myself out. The riding wasn’t too bad with the weight on my bike as long as I didn’t try to go fast, and to my surprise, I made the climb without it being that bad. In fact, I still managed to pass some cyclists on the climb.

Everything went fine until I got home. I hit the driveway a little fast, which has a sudden uphill slope from the road, and this dynamic shock caused my rear pannier rack to shear off the mounting screws. All I felt was a bump, and then there was a sudden snap as it felt like I just started tugging a block of concrete, stopping me cold. I went out for some last minute errands, including getting some stronger metal grade screws, and extra screws and other supplies.

Because the screw sheared off, half of the screw was still wound into the threads on my bike frame, and only after drilling a griping hole to unscrew this segment with some special tools was the bike mechanic able to free the hole for the replacement screw. There was no way I would be able to carry the tools needed to fix such a breakdown if this happened again on route, so if the screws sheared off while on my ride, I would have no way to remount the rack. I would have to be very careful on my trip to avoid this type of breakdown, especially since hitting holes and bumps at speed would be unavoidable on the trip. I made a note to always check the mounting screws before and after each ride and retighten them if they came loose to avoid subjecting them to an extra dynamic shock from any bumps.

As much as I had hoped to be better prepared, I was out of time, and things seemed to barely be ready enough to go through with the trip. So I set off.

Top & Table of Contents

-

Part 0 - Cycling and Scrambling from Calgary to Vancouver

-

Part I - Calgary through the Canadian Rockies

-

Part II - Lake Louise & Lake O'Hara Areas

-

Part III - Mishaps in the Middle Ranges

-

Part IV - British Columbia's Desert?!

-

Part V - Crossing the Coastal Range to Vancouver

-

Epilogue

-

Images

Part I - Calgary through the Canadian Rockies

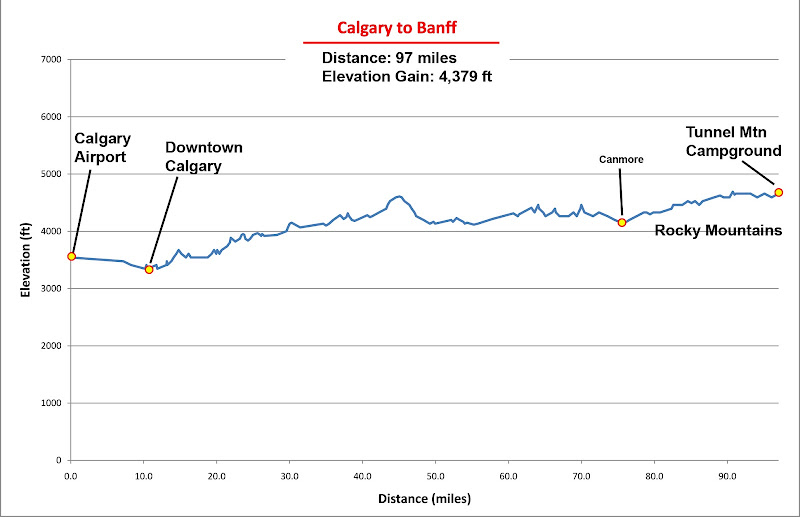

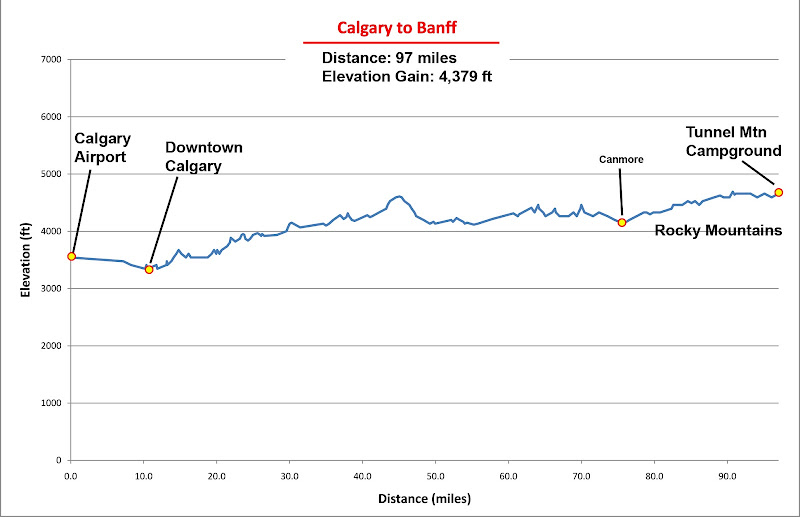

Day 1 – Starting Out - Calgary to Banff

By Bike:

By Bike:

Distance: 97 miles

Elevation Gain: 4,380 ft

My plan for the day was to take a red-eye flight from Salt Lake City to Calgary, so that I would arrive early in the day, giving me a full day to ride. My objective was to cycle some 65 miles or so to some campgrounds just short of Canmore. The idea was better in theory than in practice - a whining infant on the flight helped give me a 24-hour sleep deficit before starting my ride.

I touched down sometime around 5:30 am. I had carried two of my panniers, full, onto the airplane, and everything else was neatly packed inside my bike box or my Andanista Wild Things mountaineering pack, which were picked up without incident at the baggage claim. With a roller cart fully loaded with the gigantic bike box and all my equipment, I faced the next crux in the day’s plans – customs:

Customs Officer: “So how long are you planning on spending in Canada?”

Me: “About a month”

Customs Officer (looking suspicious): “Reeeeally? And where will you be staying tonight and what will you be doing during your stay in Canada?”

Me: “I don’t know exactly where I’ll be staying tonight; hopefully somewhere in the Rocky Mountains.

I’m planning on cycling and hiking my way to Vancouver.”

Customs Officer (raising an eyebrow): “Uh huh . . . well . . . on you go (waving me through)”

So far so good.

Assembling my rig, however, was another matter. I set up shop on the loading/unloading curb of the terminal, unpacking all of my bags and bike frame from the box, and I spent the next hour and a half repacking things for the ride and assembling my bike. Pumping the mountain bike tires with a hand pump was very trying, and something I really hoped I’d only have to do this once. Assembling the front rack with my small, awkward multi-tools was also tedious. At least I was providing entertainment for the Pakistani taxi drivers that had begun to gather around my scene, taking an interest in the mess. Naturally, they all thought I was crazy.

Starting out from Calgary International Airport

Starting out from Calgary International Airport

By 7:30 I was set up and cycling my way out of the airport terminal and on the frontage road towards Calgary. The morning was amazingly clear, and it was surreal and somewhat intimidating to see downtown Calgary in the distance, and the Rocky Mountains, still further away, rising high above the Great Plains. I felt more than a little intimidated. This was my first trip to a foreign country completely alone with no one waiting for me (as foreign as Canada is), and the plans for my first day seemed huge. Biking all the way across Calgary as just a warm up seemed a large task. I felt a tad vulnerable and exposed. Could I really make it all the way to Canmore? What was I getting myself into? Well, I was finally committed, and this added to the suspense.

Once I got into a good cycling rhythm, I forgot about my worries and began enjoying the experience. I was gradually getting used to handling my bike with its heavy load, which was a good thing since I was about to experience my next challenge - Canada’s ambiguous freeway system. My understanding (Canadians, please correct me if I’m wrong) is that many of the freeways in Canada are distinctly different than U.S. freeways in that they aren’t limited access. Basically, large boulevards eventually had overpasses, underpasses, and onramps built onto them, and most of these routes still allowed pedestrians and cyclists. Plus, there wasn’t much of a good alternative route left once these boulevards had been converted.

Approaching downtown Calgary, with my route in the foreground

Approaching downtown Calgary, with my route in the foreground

So with the high rise buildings of Calgary looming large, I found my way onto the “freeway”, hugging the right shoulder as much as I could. I could really feel the wind from passing vehicles, not only from their size, velocity, and proximity, but also because with all of my gear, my bike had a lot more surface area to catch the side wind. As I approached the river crossing on my route through the downtown, it appeared I had no option but to go up the highway bridge that arced over the water. This felt sooo wrong, both because the shoulder got a lot smaller (although I still was able to stay out of the traffic lanes), and also the feeling of cycling on a narrow overpass felt like it should be illegal (anywhere in the U.S. it sure would be). I sprinted on this part to get it over with as fast as possible, and soon I was spit out onto the downtown streets and onto the riverside promenade.

Calgary Riverside Promenade

Calgary Riverside Promenade

The promenade offered both a very nice way to see some scenic parts of Calgary and a clear through-way through much of the city with no cars to contend with – only early morning joggers and skaters. My getup was very suspicious in this urban environment, and at one photo stop a cute woman in her late 20s, probably on her way to work, approached me to ask what I was up to:

Woman: “So where are you cycling to today?”

Me: “The Canadian Rockies, on my way to Vancouver.”

|

| Prairie Cycling |

In a response that became typical along my trip, she was at first surprised, next questioned my sanity, then took interest, and finally wished me a pleasant journey.

Eventually I crossed the river, cycled up my first mild hill (ugggh!), and found a Denny’s near the West end of town where I had a leisurely and ample breakfast. This brought up another problem as there weren’t many places to lock up a bike on my trip, and even if I could, locks would do nothing to protect all of my valuable and vital equipment that I had in my panniers. As would happen on many of my stops, the employees where nice enough to let me wheel my rig partway inside where it was out of site outside and where I could keep an eye on it.

Next I was on my way out of town, entering the next critical point of my journey – finally leaving the city and hitting the open road. I had expected this leg of the journey to be rather straightforward – just a lot of flat ground and perhaps some bad headwind. What I hadn’t counted on was how much the terrain could roll at just a low enough relief that I missed it on my topo-map survey. Although the hills were mild, the ride from Calgary to the mountains was anything but flat, but rather, it was an endless series of 80-100 ft hills.

Still, they weren’t so bad if I shifted to the correct gear, and on this trip I was to follow a new, more meditative strategy that I would tell myself: “Ignore your speed, only focus on the now, and pace yourself so that you can go all day. Sustainability is key here, not time. If you feel like you are working hard, ease up or lighten the gear. Eventually you will get to where you are going. And NEVER use the granny gear – if you really need to use it, then you don’t have a prayer making it over the ‘death pass’.”

Another surprise along the road was experiencing the effects of traffic on a touring rig – especially the effects of semi-trucks, small trucks, and RVs. On an unloaded bicycle on most roads, these are just intimidating nuisances, but when they are moving at high speeds, the turbulence they kick up really packs a punch, especially on a touring rig. First, a front wave of compressed air being driven forward by the vehicle hits you, knocking you forward and then away from the vehicle as it passes you. Then you enter the low-pressure suction zone behind this wave, which sucks you sideways towards the vehicle.

|

| My sweet rig |

Finally, there is the rear suction of the vehicle, which smacks you from behind again as the vehicle passes. This whole dance of wind forces plays out in about 0.5-1 seconds and with a touring rig it was strong enough to cause a crash. You have to counter lean and steer, while controlling the inertia of the touring rig as it inevitable just moving side to side. This was even the case when I was 5 or 6 feet away on the shoulder. Even passing RVs could cause a crash from a moment of carelessness.

Another unexpected hazard is the constant encounter with small cracks, holes, and debris on the shoulder. Such small hazards cannot be seen from far away and are invisible to cars. But they are large enough to cause a crash or a flat on a bicycle and you really can only see then a few seconds before impact, so you had to be ever alert of the road surface while riding. Between the road surface hazards, and vehicle hazards, cycling was not something that could be done carelessly. Constant attention had to be paid with lots of reacting. However, as the miles wore on in my trip, this attention and reaction became more automatic and part of the background, just as much of the hazard considerations are in climbing – sort of a semi-conscious attentiveness and reaction.

The miles reliably ticked by, and occasionally I would get glimpses of the Canadian Rockies getting ever closer – things were finally becoming real. I was making much better time than expected, and by early afternoon I was approaching Canmore. At the time of this trip I was ignorant of proper sports nutrition for ultra-endurance events, and since breakfast all I had eaten was 2 cliff Bars and a couple of GUs. Not only was I famished, but I began to hit the wall big time. I barely manage to crawl into a gas station a few miles short of Canmore, bought a lot of salty carbohydrate-loaded junkfood and Gatorade to clean out my palate and replenish my energy and pigged out in the back parking lot before falling asleep tangled in my bike in some shade behind the store.

They're getting closer! I think?

They're getting closer! I think? |  Mountain, just outside of Canmore

Mountain, just outside of Canmore |

Gap Peak

Gap Peak |  Nearing Canmore

Nearing Canmore |

About an hour later I awoke and, feeling much better, decided to forgo the closer campsites and push on into Canmore for an early dinner. After a nice filling dinner and conversation with a random U.S. expat that I met at the fast food joint, I saw that it was still only 6 pm, and that the Banff campground was only another 15 miles or so away – I could easily make it there by nightfall. The prospect was too tempting and I was feeling too good to stop early, so I merged what I had conservatively planned for 2 days and continued on towards Banff. On my way out of town I came across another solo touring cyclist who was just finishing a ride of his own from Vancouver to Calgary! After getting some valuable beta on road conditions and the pass he cycled over to Kamloops (he didn’t come via the dreaded ‘death pass’, but one that was still notorious), I continued on to

Banff National Park.

Mountains above Canmore

Mountains above Canmore

I made it to the turnoff from Canada Highway 1 as it started to get dark. After one last unexpected hill (painfully steep) to get up to the hilltop campground (and then another hill along the way), I made it into the campground about an hour before sunset. I felt really beat, but surprisingly fresh considering how much I had cycled. My previous distance record, set during my training rides in July, was 54 miles, unloaded. Today, my first day of the tour, I cycled 97 miles with around 80 lbs on my bike!

With no campsite reserved, and a desire to avoid the high price for a spot, I cruised the campground looking for some people willing to share a site. One benefit of touring solo is that it is much easier to do this if you’re alone. In no time I found a campsite that was being jointly shared by a number of solo and paired adventurers who were happy to have me as company. Technically there were too many people on the site, but we agreed I would sleep in my bivvy sack just over the hill crest and pack it up each morning so that it wasn’t obvious how many people were sleeping at the site. A couple of the people had just finished working for the summer and where cycling around Banff. Another guy had just finished his summer off in British Columbia, and hitchhiked out here on a whim to find work in Banff and explore the area before heading back to school in Ontario.

After getting settled, I got back onto my unburdened bicycle and continued cycling towards town. I was told there was a convenience store about 2 miles down the road, and I was desperate for tasty food and beer. At the store I met another touring cyclist who had just finished a ride down from Jasper. He showed me some video he recorded on his cameras of all of the bears he saw along the way. I hoped to see some wildlife, but hopefully not too much of that type!

After glorious beer, I came back to the campsite for a nice fire, more beer (my friends had invited more friends), and an early sleep in order to be rested f and up early the next day to climb Mt Rundle.

Day 2 – Rainbows in Banff - Rest Day

On Foot:

Destination: Tunnel Mtn

Distance: 8 miles

Elevation Gain: 1,020 ft

I awoke to cloudy skies and rain. Noooooo! It looked like Mt Rundle was out of the picture, since it is a good haul, and tempting fate with thunder or wet rock seemed like a bad idea. Today would be an unplanned rest day, and I guess I needed it.

|

| Rainy day in Banff |

Being lazy, I took a campground shuttle into town where I spent most of the day wandering around doing errands and getting to know the place. At one point I stopped in at the ranger station to get some info on a possible day hike. Right before I left on my trip, my dad strongly recommended that I try to find my way into an area in Yoho National Park called Lake O’Hara. The lake was 10 miles away from the highway, but the road was closed to cars and bikes. The only way to get there was to hike, or take a reserved shuttle. Reservations often needed to be made weeks in advance. Once up there, the only camping available was available only by reservation 6 months in advance, and it usually filled up 6 months in advance. This makes the area relatively inaccessible to most people, but my dad suggested that I still try to find a way to get in there.

Hiking 20 miles on dirt road just to get to and from the Lake seemed like a raw deal, so I was considering hiking over the continental divide on a 20-30 mile day hike, but which route? My dad was certain that you could hike up to the Abbot Mountain Hut from Lake Louise, but from what I could tell from topo maps and Google Earth, this looked very unlikely. The ranger I spoke with said this way was not advisable since the canyon headwall to gain Abbot Mountain Hut from the East was called “The Death Trap”, as it was about 60-degree alpine ice, heavily crevassed, corniced, and within range of the regular rock and snow slides pouring off of Mt Victoria. I had another route in mind via Moraine Lake, but according to the rangers, this also required travel on a glacier that I would not want to do solo.

However, I was in luck. While the ranger was trying to discourage me from attempting to day hike to Lake O’Hara solo, a reservation at the Lake O’Hara campground was canceled. The ranger came back to me with an offer to take the site, which I did without hesitation. Based on my plans, I wouldn’t be finished in Lake Louise by then, but I could always come back before continuing West. The rangers in Yoho would even be nice enough to take my bike up in their pickup truck, despite bicycles not being allowed up there. This was for my bike’s security, and as long as I wasn’t caught riding it, they were fine with it up there.

Just to make sure I understood how to store food properly for some of my en route peak bagging, I checked with the ranger on this. It turned out, after explaining my unique bicycle situation, that this ranger was the one I had spoken to on the phone a few weeks earlier when I was planning the trip! I guess he didn’t think I would actually go through with the trip when he said I could hang food, just out of sight of the trailhead, because all of a sudden he said I couldn’t do that. The only option would be to leave food at the campground lockers, forcing me to make my peakbagging plans solely on basing out of campgrounds.

The ranger repeated the warnings about British Columbia’s desert but was happy to see that I had since prepared for it. After hearing about the weight of my bike, he also was really concerned about me cycling over Roger’s Pass, the next major pass after the Continental Divide. I knew it would be a doozy, but still nothing compared to the ‘‘death pass’’ later on. After showing him my printout of the route profile to prove that I knew what I was getting into, he seemed content, we chatted a bit more, I asked again about trying to reserve a campsite in Lake Louise (he insisted that I would have no problem getting a site, so no need to bother), and then I took off to wander more.

As I walked through town, I found a very nice riverside trail system. The system links up with marshes to the north, and follows the river down to some waterfalls just south of town. Along the way are some nice informative signs about the area and nice views of the Banff Springs Hotel across the valley.

By the time I reached the end of the trail at the rapids, I was close enough to Tunnel Mountain that I decided to wander up it for some panoramic views. Tunnel Mountain wasn’t really a mountain in my opinion, since it is just a small hill that rises 700 out of the town of Banff. The trail was steep but very well maintained, and I saw several train runners on my way up.

Once I gained the summit ridge I began to catch glimpses of nearby Mt Rundle through breaks in the trees. I came across one of these views just as a magnificent rainbow had formed in the valley below, its complete spectrum of vibrant colors stretching from the left side of the valley clearly across, terminating at the base of Mt Rundle. It was surreal to see such a perfect rainbow from up high, and especially with such nice composition! I had just enough time to snap a couple of photos before it disappeared – despite seeing many people on the trail that day, I think I was the only one who ever saw the rainbow.

![2008-07-30 - 05 - Banff]() Rainbow by Mt Rundle, seen from Tunnel Mtn

Rainbow by Mt Rundle, seen from Tunnel Mtn

After a short nap on the summit, I descended to the road and walked back to the campground. I arrived shortly before sunset. Rain had been on and off that day, but nothing too bad. The rest day was rejuvenating for me and I felt ready to tackle the next day’s objectives, weather permitting: Climbing Mt Cory and Edith. I turned in early so that I could be up before sunrise for an early start for a very long day.

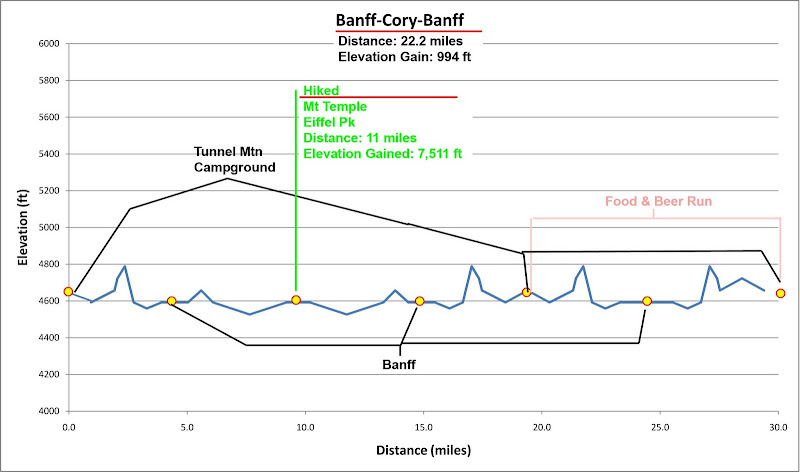

Day 3 – A Two’fer - Climbing Mt Cory & Mt Edith

By Bike

By Bike

Distance: 22.2 miles

Elevation Gain: 1,000 ft

On Foot

Destinations:

Mt Cory (9,191’),

Mt Edith (8,391’)

Distance: 10 miles

Elevation Gain: 7,500 ft

Today I was up before sunrise to get an early start on my first day of climbing in the Canadian Rockies on my cycling tour. For today, I had decided to climb Mt Cory. It was a fairly easy but scenic

scramble, and looked to be a good warm up for getting familiar with the area. Looking in Alan Kane’s “Scrambles in the Canadian Rockies,” he had a brief mention of being able to drop down to Cory Pass from the summit of Mt Cory, which sounded straightforward. This would put me only a hop, skip, slip, and a jump from the summit of Mt Edith, so I decided to tack that one on for the day too. If all went well, I would try to

traverse as many of Edith’s 3 summits as I could.

I packed up camp and locked all gear that I didn’t need for the climb in one of the spacious campsite bear lockers and stowed the rest of the cycling and scrambling gear for the day in two lightly packed panniers. As I started riding, I still felt a little sore from my first day, moving painfully slow on the hills.

![View from SW Ridge of Cory]() View from the beginning of Cory's S Ridge

View from the beginning of Cory's S RidgeStill, the air was crisp and fresh, views were spectacular, and the 10 miles to my “trailhead” went by fast. I write this in quotes because there is no trailhead for the south ridge route that I took. It is entirely cross-country and one starts from a roadside pullout on Canada Highway 1a. Due to the loop I planned to make with Edith, and figuring walking along the road would be nicer at the start of the day rather than the end.

I stopped riding where the road to the trailhead to Cory Pass intersected Highway 1a and found a place to hide my bicycle a short ways off in the trees. Walked by bike about 30 feet away from the road through some bushes, locked the wheels to the frame, and draped my handy camo-netting over the bike and gear. From the road it was completely invisible – my system seemed to be working out perfectly.

I walked along the road carefully looking for the landmarks described for the start of the route. One had to be careful to pick the right spot, as too soon will miss the ridge, and too late will put climbers on a number of the other sub-ridges that are dead-ends. About a mile in I easily found it by matching what I saw from the road to my Google Earth printout (hooray for landmarks!) and took on up the slopes on a nicely defined use-trail. The brush wasn’t too thick, and loose scree was only encountered in a few places as I climbed the headwall of the ridge, which rose very steeply from the valley. The transcontinental railroad and highway fell away below me very quickly, and I had clear panoramic views of the surrounding peaks after about an hour of fast hiking.

![Banff and Mt Rundle]() Mt Rundle and Banff

Mt Rundle and BanffJust before I gained the ridge I caught up with two lady scramblers who had parked at the turnout below. They quickly fell from site as I passed tree-line and gained the barren rocky ridge.

For such an easy route, it is still very worth doing as it is very scenic. The texture and color of the rock strata is very nice as it repeats itself in seemingly endless parallel rays. The upturned layers have also eroded into some very interesting rock formations and give the ridge an interesting architecture. The ridge often looks a tad harder than class 2, but slots in the cliffs parallel to the ridge keep providing ways to wind through.

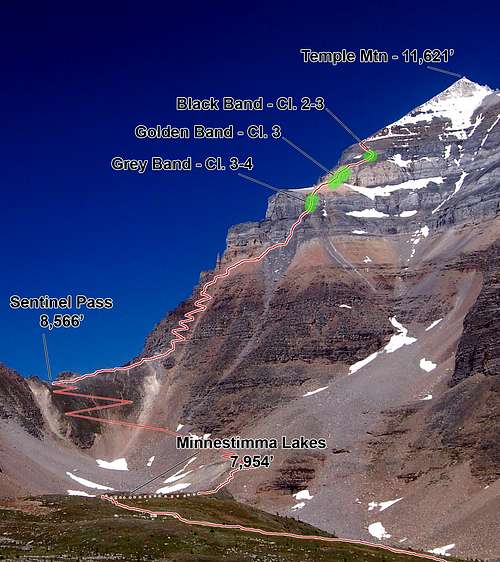

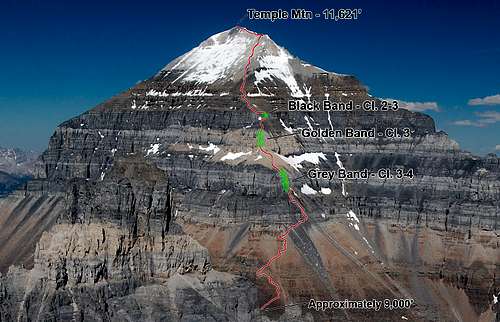

Being at a bend in the Bow Valley, the ridge also has a lot of prominence, providing stellar views of Cascade Peak, Mt Norquay, and the summits of Mt Edith to the east. To the south are nice views of Mt Rundle rising above Banff, and you can clearly see Mt Assiniboine. It is only an 11,000 ft peak, tiny by California standards, but it is so rugged, and the low valleys in the Canadian Rockies give special status to such peaks, as any 11,000 ft peak in this range has a huge prominence, often between 5,000-6,500 ft. To the north you could clearly see all of the summits above Highway 1 stretching as far north as Lake Louise, with the 11,000 ft Mount Temple being easy to spot.

| ![The South Ridge of Mt Cory]() Cory's S Ridge

Cory's S Ridge | ![South Ridge of Mt Cory]() Cory's S Ridge

Cory's S Ridge | ![Views from Mt Cory s S Ridge]() Cory's S Ridge

Cory's S Ridge | ![Mt Cory Summit View - NW]() Cory's S Ridge

Cory's S Ridge |

The route was going straightforward, but near the summit the ridge began to look more rugged and I was lured off the crest and onto a deceptively easier looking path on the east side of the slopes. This turned out not to be the way to go as I quickly found myself on my first bit of frighteningly loose and steep scree in the Canadian Rockies. Here the soil was hard-packed with rocks creating nice ball-bearings, and the slope seemed steep enough to really get going if you fell. I slowed down considerably as I nervously crawled through this section, gradually learning how to use my trekking poles to help move through such terrain.

I couldn’t get off the slopes as the way above got much steeper, so I pressed on, expecting to find a weakness back up to the ridge. Finally I found one, although it was a very thin class 3 scramble with very loose rock, with the nasty loose slopes beneath me, so I still climbed very cautiously back up to the ridge, topping out right on the West summit. Next I traverse to the East summit, which is a short ways away along a knife-edge ridge that is usually corniced. Today it wasn’t, but there was a very steep snow crest on it, and my ice axe was very helpful for safely ascending the face onto and across this traverse. I made the East summit just as the lady scramblers, who had stayed on the ridge and therefore didn’t waste time, were reaching the West summit.

The East summit was far more exposed than the equally high West summit, with drop-offs on 3 sides. How could one get to Cory Pass from here? The route down to Cory Pass was described as leaving from the East summit about 200 feet towards the summit saddle with the West summit, descending a chute to the pass, so I reversed my path back to the saddle and then began picking my way down the scree-covered slopes funneling into a chute below. The lady scramblers must have been wondering what I was up to here, as this turned out not to be a well-traveled route.

| ![Mt Cory Summit View - SE]() South East from Summit

South East from Summit | ![Mt Cory Summit View - NNW]() North West

North West | ![Mt Cory Summit View - N]() North

North | ![Mt Assiniboune from Mt Cory]() Assiniboine

Assiniboine |

It was very hard route finding down the slopes as there were many cliffs and slabby barriers in the way, and I had to be cautious not to get too close to those hazards, or boxed in where I would have to re-ascend the loose scree. As I knew I was a good ways West of Cory Pass, I kept expecting to see a break in the rocky ridge to the East where I could stop descending and traverse over. But no break appeared. I kept doing down, the terrain becoming steeper and route finding more complex as I went. This was not was I was expecting for the day, and the guidebook had made no mention of this. The only signs of life here was part of a deer skull melted out from some avalanche debris, and eventually I reached the bottom of the chute as it fanned out into the larger canyon for Cory Pass. At this point it was obvious that I had dropped far below Cory Pass. I saw the trail gradually ascending to it on the other side of the canyon, and it looked to be about 1,000 ft above me. Crap!

| ![Looking down the SE Face of Cory Peak]() The SE Face

The SE Face | ![the Southeast Face of Cory Peak]() Looking back up

Looking back up | ![Cool Strata]() Cool Strata

Cool Strata | ![The descent from Cory Peak to Cory Pass]() The 'little' detour

The 'little' detour |

In order to avoid losing any more elevation than I had to, I cut across a sliver of forest, taking care to not get into too thick of brush, since I was bushwacking alone in bear country far off the beaten track. I then ascended the main rocky was of the canyon and picked my way straight up a sandy ridge back up to the trail just below the pass. This added a hard extra 1,000 ft of gain for the day, which I was not expecting. Now the day was getting late and I had to hurry to summit Edith and make it down before dark, since I still had a 10-mile bike ride back that I didn’t want to do in the dark.

![The Sundance Range]() The Sundance Range from Cory Pass

The Sundance Range from Cory Pass

I could see why Cory Pass was a popular place to hike through. From the pass you have spectacular views of the Sundance Range and Valley, 40-Mile Creek, and rugged Mt Louis. Mt Edith’s highest and most northerly summit was only about 500 ft above the saddle, but time-wise it was much further away than I had expected. There was a nicely worn use-trail that cut up the ridge through the scree, approaching the exposed base of the summit block in a small alcove.

| ![Mt Edith North Summit Route]() Mt Edith Route

Mt Edith Route | ![Mt Edith Summit Traverse]() Mt Edith Traverse

Mt Edith Traverse | ![The summit block of Mt Edith]() Backside of the summit

Backside of the summit | ![Mt Louis and 40-Mile Creek from Mt Edith]() Mt Louis

Mt Louis |

There was one chimney in the alcove that looked doable for scrambling, except it was a 15-20 ft high off-width crack, and it didn’t look like the class 3 advertised for the summit. My guidebook said that the summit block crux was climbed via south-facing chimneys, so I picked my way down and around the summit block to the south side. Here the chimneys were flared, angled, and vertical to overhanging. They looked like hard 5.6-5.8 to me. Around the corner – well, there was no corner as there was only a very large cliff on the other side of the summit crest. I figured the guidebook had south-facing mixed up with north-facing and tentatively tried the first chimney that I found (which apparently is the right way).

The off-width chimney was just wide enough to wriggle into at the bottom, and then climb halfway embedded up the crack. My first attempt failed as I couldn’t do it with my pack on – too confining. I left my pack and (sadly) camera at the base and tried again, sweeping gravel off holds inside the crack and kicking out loose gravel and scree on footholds. The top transitioned into some nice stemming and then some crimpy face climbing to get out of the crack, followed by easy scrambling to a false summit.

The real summit is very exposed – one has to down climb off the steep backside of the false summit into a notch (crimpy and edgy class 3), and then up some steep slabs with some slightly more secure thin cracks to the high summit. This entire section has good exposure, fractured loose rock, and bad fall consequences, and as I was climbing solo out here, it took me a little while to work up the nerve, ignore my fear of heights, and sneak over to the summit and back.

On the descent I found rappel slings on the side where the guidebook said you should ascend – definitely not the way to go, but a good option for saving time for a traverse of the summits. At this point it was late enough in the day, I was moving slowly enough, and the loose rock had me nervous enough that I decided to forgo traversing to the other summits. Maybe it was because I was climbing completely alone, far away from any real security, that made me so tentative, or that I just haven’t been scrambling on loose rock in a while, but I was surprised at how loose the rock seemed to me here. It was worse than anything I had encountered in most of the Western ranges in the U.S., and seemed only slightly better than the rock in the Cascade Range!

Luckily, down climbing was easier and soon I was reunited with my pack and hustling down the trail, racing daylight. I turned on my I-Pod to some hustled down the trail, passing two backpackers heading up about halfway down to the valley. My feet were aching and I practically limped back to my bicycle. Today was a much longer and more tiring day than I had expected! Surprisingly, I felt much better being back on my bicycle, and I made it back to my campsite just after dark.

Exhausted, I was also famished and my touring food seemed inadequate and unappetizing at the time, so I asked my campmates about places to eat in town. They recommended a place, but warned me that the shuttle t town would stop running by the time I would be returning from dinner. So back on the bicycle I went, racing to town just in time to find to find all of the restaurants closing. My last hope was a bar, which surprisingly had good food and even better beer on tap. I thoroughly enjoyed my carb-loading beer fest, ate nearly 2 dinners, and once refreshed, biked back to camp and turned in around midnight. This was all right as the next day I had decided only to cycle the 40 miles to Lake Louise and forgo any plans to hike or scramble, so I could have a leisurely day.

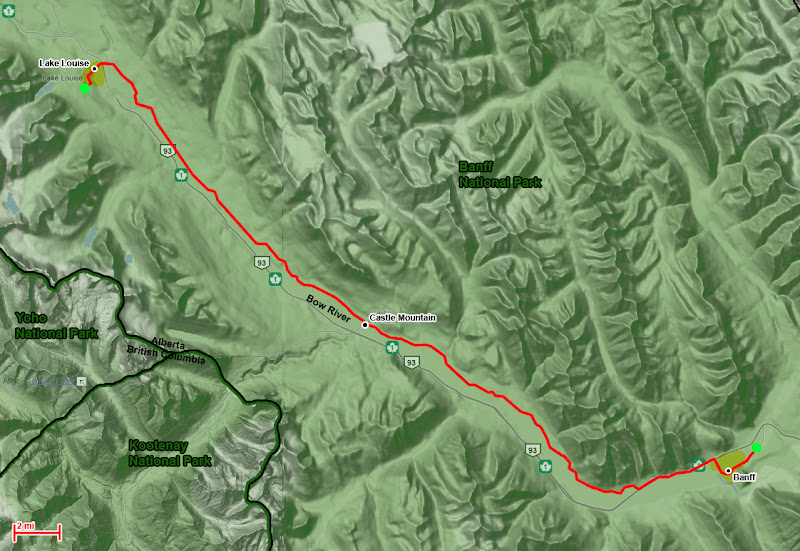

Day 4 – Moving on in Unsettled Weather - Banff to Lake Louise

By Bike

By Bike

Distance: 43.5 miles

Elevation Gain: 2,180 ft

Today was to be an easy day. I would pack up camp and set out again on my touring rig for a 40-mile ride to Lake Louise. Based on topos, the route looked really flat. Because I wanted to see some wildlife on my ride, and because I was getting tired of the noise and wind blasts along the main highway, I decided at the spur of the moment to ride on Canada’s Highway 1a, which paralleled the main highway but was much smaller and more heavily wooded.

When I woke up, it was apparent that the day wouldn’t be as straightforward as I had expected. The rains had returned, but today the sky looked much more threatening. I was determined not to get caught in a deluge on the way to Banff, since I would have very little protection from the rain and little reprieve to dry out and warm up as I had no vehicle, tent, or motel room to escape into. This could especially be a problem since it was still getting down to freezing at night.

Still, I only needed half a day of dry weather to make it, so I planned to sneak in my ride between bouts of bad weather. The Canadian at my campsite that was looking for work had found a job in town at an outdoor clothing store, and he was fine with me cycling into town and leaving my touring rig at his work while I got breakfast and waited out the weather. Then, if things looked better, I could pick up and go at a moment’s notice.

![Stormy weather near Lake Louise]() Uncertain weather

Uncertain weatherI spent the morning hanging out at a nice breakfast joint n town call Melissa’s Restaurant, recommended to me by the locals and buzzing with business. I had a nice chat with a lone man that was there for surgery (apparently Banff has some great surgeons drawn there for the outdoors) and was ready to go when a deluge started. So much for cycling! So I decided to hang around, reading and living off of coffee refills. Hanging out there, alone, in my unusual cycling clothes brought some attention. In addition to the lone man I talked with, I caught the attention of Jacquie, a pretty waitress that was serving me coffee. Gradually over the morning I told her about my trip, and also about my Denali climb (which another co-worker of hers took a great interest in). She was familiar with San Francisco after traveling there for some teaching seminars, was from Easter Canada, but spending her summers working in Banff and getting into the outdoors and vibrant art community there. When I finally decided to leave to avoid taking up too much space, she gave me her card to keep in touch. My, Canadians are friendly!

The rain had stopped and the sun was peeking out, but the clouds still didn’t look too friendly. I figured I’d wait an hour more and see how things were developing, so I hung out at a coffee shop across the street from where I left my bike. The weather stayed dry, the clouds were slowly getting better, and the road had dried out, at about 1pm I hopped on my bike and took off.

Oddly, the 7,500 ft day of hiking and scrambling the day before, while leaving my legs sore and tired for walking, didn’t do much to me for cycling. I felt refreshed from my traumatic first day and made good time. Occasionally the clouds would look more threatening, but I lucked out and never felt a drop of rain the entire day. Still, the day wasn’t without more surprises. One downside to taking the smaller side road to the main highway was that it followed the landscape more – lots of winding, which was nice, but there were also no road cuts.

The road would go pretty flat for a while then hit a ridge coming down from the mountains. Here the road would just angle slightly and climb straight up the steeply at 5-8% grades, dropping just as steeply down the backside as soon as the crest was reached. Similar to my ride across the plains, these hills were only about 200 vertical feet in height, just below the resolution of topo maps, but they were very intensive, psychologically demoralizing (since I descended as soon as I finished climbing) and added up to some 2,000 feet of elevation gain where I had expected only about 400 ft!

Near the end of my ride, these steep hills had taken their toll and I was tired, even though I had only been riding about half a day. I knew I was close to Lake Louise when I came across a lone cyclist that was doing a little foray out from town. The cyclist was having some problems with her cycling gears, so I welcomed the opportunity to stop and help out. After she was set on her way, I quickly made it into town and then over to the campsite.

Mt Temple seen from Highway 1a

Mt Temple seen from Highway 1a

As I approached the campsite entrance, things didn’t look good. The road was lined with signs saying the campground was full! Damn that ranger in Banff! Apparently this was a major holiday weekend in Canada, which the ranger hadn’t considered when he told me not to worry about making reservations. The station attendant said Castle Mountain still had space, to which I gave him a look, told him about the ranger in Banff, and also pointed out that I had just cycled from Banff in my fully loaded touring rig, the campground was 10 miles back the way I came, and that sunset was in about 30 minutes. Ergo, this information would be helpful to someone driving in a car, but not to me. Then the ranger took pity and gave me permission to just wander the campground and see if I could find someone who wouldn’t mind sharing a spot. He gave me some recommendations on where to look and let me on my way.

Searching was a bit stressful as I was in a hurry to find a place to bed down before nightfall, and I made rounds to every campsite in the area, and the few that looked promising had campers that weren’t interested in sharing. I made a 3rd final loop and saw a new camper who had just got back, who was old (but not too old), male, and alone, so perhaps would be open to sharing the cost for his site.

The man’s name was Andre, a Swiss who was taking a year off from work to travel through North and South America. He had bought a car for the trip, which he planned to sell in the U.S. as he didn’t want to be driving it down through Mexico and South America, where expected to end his trip sometime in June 2009. He was more than happy to have the company for the next couple of days and we got along great talking about the U.S., Canada, Switzerland, my latest travels and plans, as well as his. Andre was an active guy, running at least 10 km a day, even on his long driving days, and he had been seeing a lot of the area on his runs. Apparently Andre had already been through Kamloops, so upon hearing my plans asked:

“Why on earth would you go through Kamloops? There is nothing to see there and the few trees there are all brown!”

Brown trees? Come on, it can’t be that bad . . .

Top & Table of Contents

-

Part 0 - Cycling and Scrambling from Calgary to Vancouver

-

Part I - Calgary through the Canadian Rockies

-

Part II - Lake Louise & Lake O'Hara Areas

-

Part III - Mishaps in the Middle Ranges

-

Part IV - British Columbia's Desert?!

-

Part V - Crossing the Coastal Range to Vancouver

-

Epilogue

-

Images

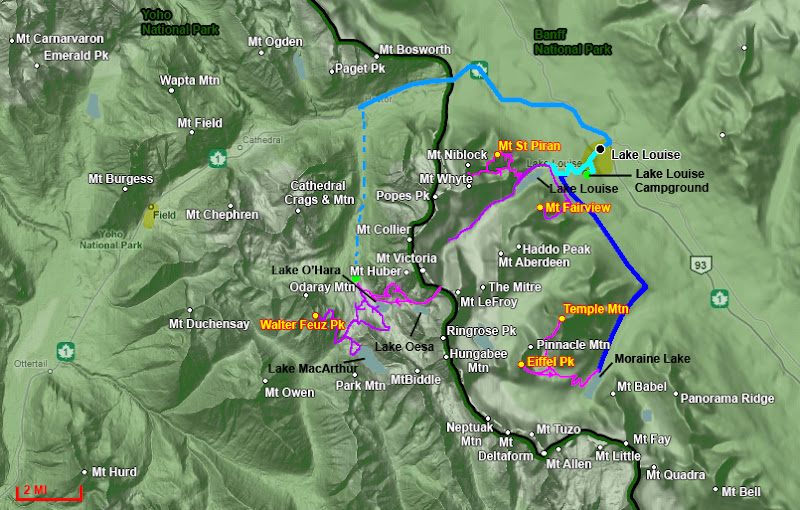

Part II - Lake Louise & Lake O'Hara Areas

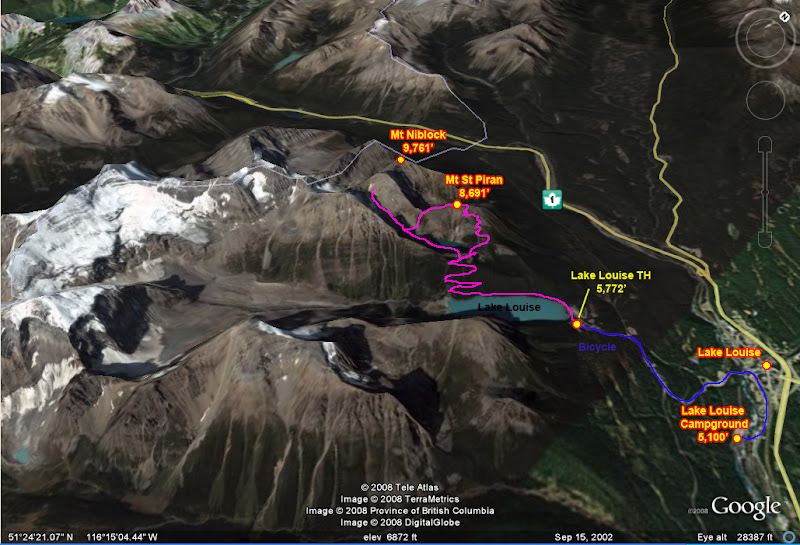

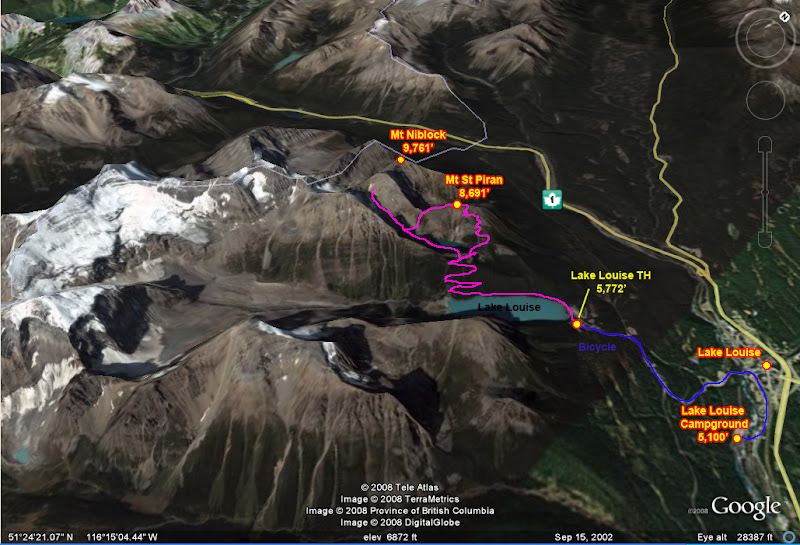

Day 5 – More Climbing - Climbing Mt St Piran and Mt Niblock

By Bike

Distance: 7.6 miles

Elevation Gain: 700 ft

On Foot

Destinations:

Mt St Piran (9,761’),

Mt Niblock (DNF)

Distance: 9.7 miles

Elevation Gain: 3,620 ft

Today I was ready for another double peak day. On the agenda today was to cycle the short but steep climb to

Lake Louise. From there I would ascend Mt St Piran via the

main trail, and then traverse over to the

main route of Mt Niblock to link up the peaks. Today promised more wonderful views, good weather, and much less distance and elevation gain than my first scrambling day.

![Mt Whyte, Niblock, & St Piran]() Mt Whyte, Niblock, & St Piran

Mt Whyte, Niblock, & St Piran | ![Mt Whyte, Niblock, & St Piran]() Mt Whyte, Niblock, & St Piran from the Lake Louise TH

Mt Whyte, Niblock, & St Piran from the Lake Louise TH |

I left camp at 9:20 am, making it to the Lake Louise trailhead a half-hour later. The climb to Lake Louise was pretty intensive 6% grade for 700 ft, but still not nearly as steep as the ‘death pass’ that I so feared. Before I knew it the climb was over and I was setting off on the trailhead at the Lake Louise circus grounds. The place was packed! After being mostly by myself for the past few days, only seeing people in town, seeing so many tourists on the trails here was – well – annoying. I locked up my bike and took off as fast as I could (on this day and others I opted to leave panniers back at the campground and ride to the trailhead with all of my gear already stowed in my backpack, which worked much better for leaving my bike).

The most difficult part of climbing Mt St Piran was passing all of the tourists on the trail. Luckily, they mostly faded away after the Tea Hut, and the smaller trail (more of a use-trail really) to the summit was easy to find if you were looking for it. I made the 3,000 ft ascent to the summit in 1:45 from the lake, and the trail made it feel effortless. From the summit I had such dramatic views of the surrounding peaks that I felt like I had cheated. The mountains were so rugged, rising nearly vertical from the many glaciers below, and yet you could be well on your way to the summit after only a couple of hours of hiking or scrambling!

![Mt Aberdeen]() Mt Aberdeen seen from Piran's trail

Mt Aberdeen seen from Piran's trail | ![Pissed Ground Squirrel]() Pissed Ground Squirrel

Pissed Ground Squirrel | ![Ice Avalanche on Mt Lefroy]() Ice Avalanche on Mt LeFroy

Ice Avalanche on Mt LeFroy |

After being harassed by an overly aggressive squirrel that threatened to leap on my face from a rock windscreen (really, squirrel, you don’t want to eat this GU packet!) and enjoying a spectacular ice avalanche off of a hanging glacier on Mt LeFroy (it sounded like a jet airplane passing overhead) I continued down the backside toward peak #2, Mt Nibock. It seemed I would wrap up this day very quickly.

The descent looked questionable, but with some carefully route finding, it stayed at a chill 2nd class, only becoming really steep where the slope became grassy. I dropped down into a lower cirque and traversed across and up to the first class 3 section of the route on Mt Niblock. The scrambling went through a weakness in the cliffs separating the upper cirque from the lower one through a weakness carved by a waterfall. From a distance it looks very technical, but the cliffs actually had numerous catwalks linked together with moderate (if at times wet and exposed) class 3 sections.

![Mt St Piran summit panorama]() Whyte & Niblock from Piran

Whyte & Niblock from Piran

The route was fairly complex but straightforward, and soon I was climbing the upper cirque. Here the loose rock changed from irritating to frightening as everything began to slide. Also, many of the rocks were only a thin layer on top of slabs, and as I wandered into the upper set of cliffs, I became concerned about slipping off over the escarpments as the scree slopes approached about 40 degrees in steepness. I made ample use of my ice-axe in the dirt, using a trekking pole on my downhill side for stability as I climbed this vertical dirt.

![The Agnes Lake Tea House]() Lake Agnes Tea House

Lake Agnes Tea HouseI was beginning to have serious reservations again about scrambling alone on such bad rock in mountains I was unfamiliar with when suddenly a number of large rocks came bouncing down the chute I was about to come up. Helmet or no, this gave me a good excuse to turn around and come down (I had taken about 2 hours to get to my highpoint here from Niblock, so not much was invested here). After descending a short ways, two climbers emerged from the chute, being the cause of the rockfall. Still not too encouraging, and I figured I might as well call it an easy day and descend with them for some company. Reversing the lower class 3 section was plenty easy technically, but because the route wandered so much in the cliffs, it was very easy to get lost since it was hard to see over the ledges.

The older man was Adrienne, a financial analyst from Edmonton and an avid mountaineer. He had led many outings for the Canadian Mountain Club, and on our descent he filled me in a lot about the club’s activities. He was leading Barry, a visiting Irishman, young guy, who was the boyfriend of a co-worker of Adrienne’s. They had summitted Niblock and said I wasn’t too far from it (doh!) but that the linkup to Whyte, which I had considered, had considerably more loose rock and exposure. In light of my nervousness with all of the cruddy rock, as we descended we bantered back and forth about mountaineering accidents and close calls in the mountains (which Adrienne, as a regular trip leader, had many in the Canadian Rockies to talk about).

I made it back into town early, so I used the time to stop by the bike shop to address some bike issues. My bike had started to make nasty crunching noises, and as it turned out, my chain had become stretched, which was fixed, and the teeth on the chain ring were dulling, which couldn’t be fixed. Also, my index shifters had been getting stuck in the clicked position, requiring me to push them back into place. This would require new parts which the shop didn’t have, so I’d just have to live with the irritation. I asked the shop to look over my bike to make sure nothing else was wrong, since this would be a convenient place to work out newly manifest issues, but all else seemed well (as would be apparent later, was they weren’t).

![Mt Temple from Lake Louise Campground]() Temple Mtn from the Lake Louise campground

Temple Mtn from the Lake Louise campgroundDay 6 – Valley of the 6 Glaciers - And Climbing Mt Fairview

By Bike

Distance: 9.3 miles

Elevation Gain: 738 ft

On Foot

Destinations: Valley of the 6 Glaciers,

Mt Fairview (9,002')

Distance: 16.2 miles

Elevation Gain: 4,780 ft

Today I must have recovered a bit more from my cycling, as the climb to Lake Louise felt much easier. Today I had two planned destinations for a moderate day out. First, I would hike up to the Valley of the 6 Glaciers, which I had learned had spectacular views, as well as front-row views to The Death Trap that my day had tried to direct me to for reaching the Abbot Mtn hut. Because I knew this area had lots of avalanche potential, I started out early in hopes of seeing some of the mountains come down with morning warming from the sun. Next I would

hike Mt Fairview, which was supposed to have excellent summit views.

The trail from Lake Louise to Valley of the 6 Glaciers is very well maintained and littered with people all the way to the Tea Hut at its main terminus (so it was good I got there early!). Beyond the tea hut the trail becomes fainter and follows a moraine crest all the way to the cliffs at the base of Mt Victoria’s gigantic hanging snowfields and glacier. Once again I felt as if I had cheated, since the hike was only a mild warm up, and at the end I was treated to one of the most picturesque views I’ve ever had in the mountains.

![Valley of the 6 Glaciers]() The "Death Trap"

The "Death Trap"![Avalanche in the Death Trap]() Avalance in the "Death Trap"

Avalance in the "Death Trap" | ![Mt LeFroy at Valley of the 6 Glaciers]() Mt LeFroy

Mt LeFroy | ![The Mitre]() The Mitre

The Mitre |

Because I had planned an easy day, I just hung out at the end of the trail and enjoyed the views, watching the occasional avalanche roar off Mt Victoria and into The Death Trap. After about an hour I realized I was feeling really beat. Being 6 days into my ride, I knew my body was still adapting to daily punishment with no breaks. Also, I had no idea how many calories I should be consuming each day, and I think I was under eating.

![Mt Aberdeen]() Mt Aberdeen from Mt Fairview

Mt Aberdeen from Mt FairviewI wandered back down for more lounging at the Tea Hut, where I treated myself to some coffee and chocolate cake from a nice second-story porch views of Mt Victoria and Mt LeFroy. At one point there was another icefall on Mt LeFroy that sounded like a jet engine. I never saw the slide, but I saw the snow plume and shockwave blow out from the cirque by the Mitre. Once again, sitting in the Tea Hut, I felt really spoiled at how easy it was to get here and how comfortably I was experiencing it – definitely more a European style to experiencing the mountains than American!

Still feeling beat I read a book for a while and spaced out, all but giving up on plans to climb Mt Fairview. Still, I didn’t want to admit defeat, and I decided I should head down and just see how I feel at the trailhead. If I hiked back fast enough, then I might have just enough time to run up the peak and make it back to the town for dinner before the restaurants closed.

![Mt Fairview seen from Lake Louise town]() Mt Fairview

Mt FairviewOnce I made it to the trailhead I inexplicably got a second wind and decided to see if I could make the 3,300 ft ascent in less than 1.5 hours. I blasted the Nine Inch Nails on my I-Pod and took off as fast as I could. The last 500 vertical feet of trail was very steep, requiring a lot of high-stepping. I guess whatever was in the Tea Hut’s chocolate cake finally hit me, because while the other hikers here were moving at a snail pace, starting and stopping, I felt lighter than air, jumping up the high-steps and half-jogging up the trail and making the summit somewhere between 1-1:20 from the trail head – ascending over 2,500 ft/hr, not bad! I’m not sure of the time more specifically then because I met some very hospitable Canadians with beer and other fun on the summit.

![Mt Victoria from Mt Fairview]() Mt Victoria

Mt Victoria![Marmot on Mt Fairview]() Marmot

Marmot | ![Mt Fairview Summit Looking NE]() NE View

NE View | ![Climbers finishing the east ridge on Mt Temple]() Climbers on Mt Temple's NE Ridge

Climbers on Mt Temple's NE Ridge |

The guidebooks were spot on when they said that this summit had one of the best views in Banff National Park, and one of the best views per effort expended. Fairview is an understated way to describe the summit. The views reminded me of those from Temple Crag in the California Palisades – the peak itself isn’t grand, but it gives you an elevated, front-row 360 panorama of all of the larger peaks in the area. Hanging out on the summit I was even able to see climbers topping out on Mount Temple’s classic

East Ridge.

From the summit I could also seem some storm clouds brewing, so I headed down in haste to avoid the imminent rain shower. It was too late, as the first drops began falling on me just as I reached my bicycle. By the time I began coasting downhill the rain picked up in ferocity and became a full on deluge. I had come prepared, for this, though, and had donned a waterproof jacket and pants shell. However, since I had never done much cycling in the rain, it didn’t occur to me that my feet would need special rain protection. Between the water spraying off the road and tires, and the speed at which I was colliding with the rain drops, within a matter of minutes my shoes became saturated with cold water. Although the descent to the valley was only about 10 minutes, my feet were already numb by the time I made it down and out of the worst of the rain.

Almost as suddenly as it had started, the thunderstorm stopped, allowing the last alpenglow of the day to cast its pink shine on Mt Temple. Although brief, the rainstorm was violent and had left me soaked and numb, revealing a serious deficiency in my cycling clothing.

Day 7 – Lake O’Hara Environs - Lake Louise to Lake O’Hara

By Bike

Distance: 10.3 miles

Elevation Gain: 420 ft

On Foot

Destinations: Walter Feuz Pk (9,348'), MacArthur Lake

Distance: 10.6 miles

Elevation Gain: 4,500 ft

Today was the day I was leaving Lake Louise to camp and hike in the Lake O'Hara area. I was still set on climbing Mt Temple, which I hadn’t gotten to yet, so I planned to return for that before continuing West. I gave my farewells to Andre, who was great enough to not let me pay him my share for the campsite, and then I set off very early to make sure I made it to the pickup point in time for the shuttle.

Lake O’Hara is in Yoho National Park, on the other side of the Continental Divide from Lake Louise. However, this was the most anti-climatic divide I have ever crossed. I had to gain an incredible 420 vertical feet over a vast 8 miles, so this would require all of my patience to not get bored. Along the way I saw some other touring cyclists heading the other way on the highway, coming from Jasper National Park (the only other touring cyclists I would actually see on the road on my trip, oddly enough.) The final few miles up to the pass were memorable for me as it was like riding some kind of stagecoach or galloping horse. About every 15 feet there was an expansion joint in the road, giving me a mild bump. The bumps were small and regular enough that it created a kind of “thump-thump . . . thump-thump . . . thump-thump . . .” that lasted all the way to the summit.

I rode very carefully on the final quarter mile to the pickup, as it was on a bumpy dirt road and I was terrified of breaking my rear rack. I made it to the stop with plenty of time to pack up my gear off of my bike and get it ready for transport. I met a number of other nice travelers there from all walks of life, and one person who offered me some great advice for returning. Although the campsite reservations often fill up 6 months in advance, it is common for cancellations to occur within a week of the reservation due to unforeseen events, so one can reasonably count on getting lucky looking for a spot less than a week before the scheduled time. Soon the bus arrived, and the ranger and truck that would take my bike up. I delivered the bike and some thank-you chocolates for the favor they were doing me (since bikes technically weren’t allowed up there) and we were off.

![Transcontinental Divide]() The extremely steep continental divide

The extremely steep continental divide | ![Wiwaxy Peak]() Wiwaxy Peak

Wiwaxy Peak | ![Mt Huber]() Mt Huber

Mt Huber | ![The Goodsirs from McArthur Pass]() Goodsirs

Goodsirs |

Once I made it to the campsite I quickly set up, ate lunch and took off. I would only have the last 3/4 of the day here, and another half day tomorrow before the shuttle took me back, and I wanted to make the most of my time in the area. The first place I headed to was McArthur Pass in order to get a view of the Goodsirs. In some earlier Google Earth reconnaissance for the trip I couldn’t help but notice these gigantic peaks towering over the area. A quick spot check revealed the north faces rise nearly vertical over 4,500 ft from the glaciers at the base to the summit! I could see from topo maps that I should have line of site to the peaks from the pass.

The pass provided stellar views of the peaks, but more was to come. The Highline Trail, which split off here, went higher up some mountain slopes, but through a protected area. The area was currently open to only 10 people each day, and there was still space for me, so I wandered up to get some higher views of the area. I neared some cliffs where the maps showed the trail ending, and seeing a use trail and cairns continuing, I continued climbing.

![SE Ridge of Walter Feuz Pk]() SE Ridge of Walter Feuz

SE Ridge of Walter Feuz

Atop the cliffs where a series of rock plateaus and talus piles, and I kept following the cairns higher. Finally I reached a high point at the base of a ridge spur coming off of the main peak and sat down to enjoy the views. I didn’t plan to go higher, since I had no guide for the area, no idea what peak this was or what routes were on it, and from here it looked like 3rd class scrambling with a vertical 200 ft headwall stopping the ridge. Ridgeline cornices also looked huge, and something I didn’t want to tangle with solo – but wait! In the opening between two cornices I saw some climbers pass. I could follow their tracks, and their scale showed that the cornices weren’t as large as though, and the summit not as high as though.

![The Goodsirs from Mt Walter Feuz]() Goodsirs from Walter Feuz

Goodsirs from Walter Feuz![Unknown Pks in Kootenay Ntl Park]() Peaks in Kootenay from summit

Peaks in Kootenay from summit | ![Ridgeline between Bosworth & Paget Pk]() Bosworth & Paget Pk Ridge

Bosworth & Paget Pk Ridge | ![The Goodsirs]() Goodsirs & Yoho

Goodsirs & Yoho | ![Ringrose Pk & Hungabee Mtn]() Ringrose & Hungabee Mtn

Ringrose & Hungabee Mtn |

Figuring they came up my way, I continued up towards the main ridge. Here I scrambled on the best rock I encountered in the Rockies. It was surprisingly solid rock on delightful third class on the spur. At the headwall, I found a series of ledges that zig-zagged across the face, keeping difficulties low, and before I knew it, after a short steep snow headwall, I was at the top. The backside was completely melted out except for the cornices, so the final bit was a breeze. I passed the climbers, now descending from the summit. They were a group being led by a guide from the Alpine Club of Canada (ACA), who were staying at some club cabins at Lake O’Hara. They told me the peak I climbed was called Walter Feuz (or Little Odaray, since it was a smaller summit on a massif with the higher and more technical Odaray Pk). Also, there was a peak across the way above Lake McArthur, Shaffer Ridge, and they pointed out to me that you could see climbers from another party of theirs scrambling up it. It apparently had good rock and reasonable route finding too, so I made a note to go for it after stopping by McArthur Lake.

![Mt Biddle & Lake McArthur]() McArthur Lake

McArthur Lake

The summit provided breathtaking panoramas of the Lake O’Hara area, and an unobstructed view of the Goodsirs. To the south, Mt Assiniboine still looked surprisingly close. As I descended, I was struck by how varied and unusual the rock was in the area. Unlike the rest of the Rockies encountered so far, this rock was much more solid. Also, a lot of it didn’t appear to be limestone.

![Mt Goat & Baby]() Mountain Goat & Baby

Mountain Goat & Baby