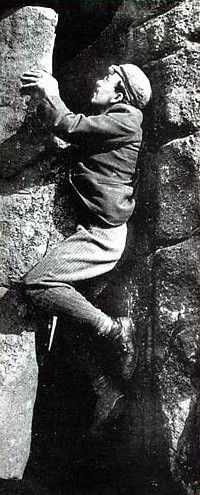

While the Alps may have become something of an obsession for Jones, he did not turn his back on his own country, and while summers, and sometimes winters, were spent among Europe’s greater ranges, the majority of his time was spent on his home crags. On Easter 1890 had paid his first visit to Wasdale Head in the Lake District, which was at the time the centre of English climbing. 1890 appears to be a pivotal year for Jones as it marks a change in his focus from the crags of Wales to those of Cumbria. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that his father died in the same year, and his connection to Barmouth and the surrounding area weakened. At Wasdale he was by chance to meet W.M. Crooke, who Jones, in the first paragraph of his book Rock Climbing in the English Lake District, was to thank for introducing him to Lakeland Climbing. Later, Crooke described this first encounter:  | | Climbers on the East side of Pillar Rock, the scene of Jones' first Lakeland climb. | | Photo: Abraham Bros. |

"Having broken away from the party with whom I had been spending most of my holiday in Borrowdale, I made my way to Wastdale Head Inn. I picked up a chance acquaintance with two young fellows in the inn, and we agreed to go together to climb the Pillar Rock with the aid of a ' Prior's Guide ' which I had in my pocket.

When we commenced the ascent, which proved very easy - I believe we went up the easiest way - the dark, slim young fellow somehow naturally assumed the lead. Before we started he had discovered that I had been to Switzerland and had done some climbs there, so he was very modest about his own powers. A few seconds on the rocks dissipated all doubt. With great confidence and speed, climbing cleanly and safely, he soon showed he was no ordinary climber. I had been out with some very tolerable Swiss guides, but never before with a man to whom rock-climbing seemed so natural and easy. My curiosity was excited. He could not be one of the great climbers, for he had never been out of the British Islands, but he could climb.

On the top we found a small, rusty tin box, in which were a number of visiting cards... One of us produced a card, on which the other two wrote their names. The dark young fellow signed his name ' O. G. Jones.' I wonder if that card is there still."

"It [climbing]satisfies many needs; the love of the beautiful in nature; the desire to exert oneself physically, which with strong men is a passionate craving that must find satisfaction somehow or other; the joy of conquest without any woe to the conquered; the prospect of continual increase in one's skill, and the hope that this skill may partially neutralize the failing in strength that comes with advancing age or ill-health”.

The next key event in Jones’ career came six years later when he made an unexpected call on a small photography shop in Keswick and introduced himself to brothers George and Ashley Abraham. Unbeknownst to the brothers, several years earlier Jones had come across one of their photographs of Napes Needle in a London shop window and it had been this moment that had inspired him to take up the sport. By now Jones was an experienced climber of some distinction. Cool of head and bold in movement, he was from the gymnastic school of climbing, able to rely on his considerable strength to push him through any encountered difficulty; this combined with his natural balance and sure footedness made him a formidable presence on the crag. It’s not for nothing that he was known amongst his friends as ‘The Gymnast’. George Abraham even claimed that "One Christmastime an ice axe was arranged as a horizontal bar . . . He [Jones] grasped the bar with three fingers of his left hand, lifted me with his right arm, and by sheer force of muscular strength raised his chin to the level of the bar three times". What’s more, his genial personality had made him extremely popular with his contemporaries; he climbed with a great number of partners regardless of their previous experience and all were said to be comfortable in his presence and to have been given confidence by his lead; the Abraham brothers for example appear to have almost idolised their friend and Jones’ partnership with the two photographers, along with his skilful self-promotion, was to have a huge influence in popularising the sport.

With the two photographers alongside he undertook an exploration of some of the most formidable crags in the Lake District, and in doing so gained a great number of first ascents to his name. For the Abraham brothers, the finest of these were Scafell Pinnacle, from the second pitch in Deep Ghyll, and Walker's Gully on Pillar Rock, both of which had long been thought to be unclimbable. Today the former is given a grade of Hard Severe, while the latter receives a grade of Mild Very Severe 4c. Technically Walker's Gully was Jones' hardest climb, which he claimed in the unseasonably mild January of 1899.  | | How do you spend your Christmas'? Jones and co. on the first winter ascent of Napes Needle, 25th December 1896. | | Photo: Abraham Bros. |

While Jones may be best known for his work on rock, his achievements on snow and ice should not be underestimated either. It’s unfortunate that traditionally winter first ascents were never recorded in Wales, so what he accomplished there remains to be a relative unknown. In the Lake District however, first ascents were recorded systematically and so we have a good idea of what was going on there at the time. Many of his winter routes it seems were simply repeats of rock routes, which owing to the season were garnished with a dusting of snow. For example, on the 25th of December 1896 he and several others recorded the first winter ascent of Napes Needle. These were not a winter climb in the true sense, since they did not require the specialist skills of the winter climber (such as they were in those early days), but there is no doubt that the addition of snow and ice would have made for a more challenging climb.

Jones did more than just climb old rock routes though and Christmas holidays were often spent in the pursuit of true winter ascents. Of these, Oblique Chimney on Great Gable and Moss Gill on Scafell Pike stand out as being the most impressive. In purely technical terms, Oblique Chimney, which is given a modern grade of IV, 5, was almost certainly one of the two most difficult winter climbs undertaken in the Lake District prior to the Great War. In Rock Climbing in the English Lake District, Jones wrote that "the smooth walls of the gully were black and shiny with ice", but this of course failed to deter him and he set about the challenge with characteristic gusto, emerging victorious an hour later. While Jones revelled in his triumph, his partner Leo Amery was feeling slightly less enthusiastic, he later wrote: "I remember being able to look down between my legs into what seemed a bottomless abyss of writhing snow. It had been snowing all day and by the time we had overcome the chimney and were nearing the top of the mountain it was not only blowing a blizzard, but it was dark into the bargain". This was on January 3rd 1893. Six days later Jones climbed Moss Gill, which while being less technically demanding (it is given a grade of IV, 4), is probably an even greater achievement for Jones ascended it solo. This is even more impressive in light of the fact he did so despite the encumbrance of a clinometer and a couple of broken ribs sustained by a fall from the Collie Step (luckily saved from worse thanks to the backrope he had fixed through a chockstone).

Though his climbing was now largely concerned with the crags and buttresses of the Lake District, he still made regular visits to Snowdonia, introducing many friends to the area, climbing almost all of the established routes and putting up many of his own. Here his Welsh roots shone through; he would humorously refer to himself as ‘The Only Genuine Jones’ and playfully chide his English companions over their mispronunciation of Welsh names. While he may be better known for his Lakeland climbs, today his most repeated line is probably the Ordinary Route on the Milestone Buttress of Tryfan, which he recorded in 1899. Today it's given the modern grade of Difficult. The Abraham brothers were to accompany him on trips to Wales in 1896, 1897 and twice in 1899 where he was to be their ‘local guide’. It is fortunate that he did so, because as events were to turn out, the brothers were to become key figures in the development of Welsh climbing. |

Comments

Post a Comment