Previously in Four months in Peru: Huascarán: One for two, struggling with clouds and a learning experience.

Uruashraju? What's that?

If you want to pronounce its name, sneeze. Quite likely you're going to be pretty close. The mountain I'm talking about is Nevado Uruashraju, a 5722m high snow peak in the south of the Cordillera Blanca. I would be surprised if you ever heard about it: it does not reach the magic 6000m mark and, although not truly difficult, it's still harder than the usual acclimatization peaks, ruling it out for most climbers. As a result, it is rarely climbed at all. I had not expected to go there either, and surely I never would, had I not encountered Pierre.

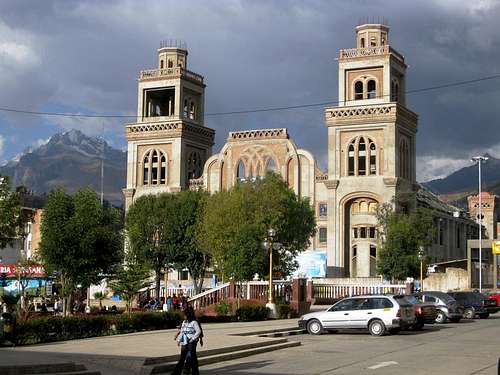

![Huaraz]() Huaraz, with the Cordillera Blanca in the background

Huaraz, with the Cordillera Blanca in the background![Jatunmontepuncu summit view]() On top of Huapi, a few weeks earlier.

On top of Huapi, a few weeks earlier.

Click here for the trip report.While I visited Peru, I regularly popped into the offices of various local agencies everywhere. Why? Well, to ask for up to date information, look for interesting climbs to join, and simply out of curiosity. And on one such occasion a couple of weeks ago, in an agency in Huaraz, Pierre just happened to walk in while I was talking with someone, on a quest for information about

Huapi.

When we first met, we both already had plans for the near future, but we kept in touch, and, finally, a few weeks later we had a matching gap in our busy schedules.

Pierre was an experienced French mountaineer, on his seventh visit to the area, so he knew it quite well. Not surprisingly, he had already climbed many of the well known routes, which explained why he was keen to have a go at a less frequented one. I, on the other hand, had never been to Peru before. Sure, I was on a very long trip, but still, in the five weeks I had spent so far in the Cordillera Blanca, I had only explored a fraction of the possibilities, and mostly the more popular ones because it was easier to find partners for those. But I was game to try any interesting route, as long I thought it was within my capabilities. So, when Pierre proposed to climb Nevado Uruashraju, I was happy to get on board.

We didn't have much information about the mountain. We had the 1:100 000 scale Cordillera Blanca Sur map, and Biggar

[1] devotes a page to it, rating it AD, with a few lines of text and a small photo sketching the route. That was it. But that didn't faze us: Solving potential problems on the route is all part of the fun of mountaineering, right? We figured we should be fine. While I had only climbed a couple of harder routes than this, I had climbed regularly at this level, sometimes even solo. And Pierre was very experienced and had climbed much harder routes, beyond anything I ever expect to do.

We asked around in Huaraz, but that didn't help much either. Uruashraju proved to be a relatively unknown, almost forgotten peak. Finally, the best advice came from Eduard, a retired mountain guide and owner of Edwards Inn in Huaraz, where I was staying. He had climbed the mountain some years ago. He thought it was a nice one, told us to be mindful of crevasses on the high glacier plateau, and wished us luck.

Getting to base camp

Through one of the agencies in town, we had arranged for a taxi to the trailhead and an

arriero (mule driver) for the hike to base camp, at the end of Quebrada Rurec. Around eight in the morning we were on our way.

The main road in the valley to the south of Huaraz was excellent, but after the turnoff to Olleros it was a different matter. There were road works going on, so we had to follow a detour. Higher up, past the last permanently inhabited dwellings, and on a dirt track by now, our Toyota occasionally struggled with the poor road, but eventually we reached the trailhead. It didn't look special and the road didn't even end there, but since that's where we met our arriero, that was it. It didn't take long to load up our gear and get walking along the now quickly deteriorating track to the entrance of the valley. The car couldn't have gone much further than where it had dropped us.

![A sign of optimism or a waste of money?]() The blue building

The blue buildingA strange building stood there. It was just a stone shell, without windows or any interior fixtures, and it looked abandoned. It wasn't run down though, and the still bright blue paint was proof that it couldn't be more than a few years old, if that. Yet there was no sign of any activity, to finish it. The way it looked reminded me of a school, but the location would be absurd for that: high above all the villages, at the entrance of a valley without anybody living nearby.

When I asked about it later, I learned that it was meant to become a lodge. The local communities had built it, hoping to attract more tourists to their region. I can see the logic: it's a beautiful area for hiking or horse riding, and besides Uruashraju, there are a lot more mountains to explore, some easier, some harder. But the only 6000-er in the area is Huantsán, one of the most difficult high peaks in the Cordillera Blanca, well beyond the capabilities of an amateur – and the ‘normal' route, if you can say that about such a difficult one, doesn't even start nearby. So, while I see some potential, it remains to be seen if the tourists will come – assuming it ever gets finished.

![Looking up Quebrada Rurec]() A view deep into Quebrada Rurec, not far from the entrance

A view deep into Quebrada Rurec, not far from the entranceAlmost a French lunch

Two hours later, well into the valley by now, we stopped for lunch. Fortunately, Pierre had had the foresight to keep bread and cheese in his day pack. The only thing missing was the wine, or we would have had a French lunch! I had been less careful and had handed my food to our arriero to carry, not expecting that he would soon lag behind. It took him 15 minutes to catch up.

It was a nice spot actually. The valley was broad and green at that point, and a small herd of cows were grazing on the grass. The hiking trail was on the side, where the walls were steep, and our lunch spot had some trees and rocks to provide shelter in case of rain – which looked like a distinct possibility at the time.

Our arriero then surprised us by announcing that, further along the track, there would be a gate for which he didn't have the key! Someone down in the valley did, and for some reason he had not wanted to hand it over to the arriero. He had asked the key holder to come join us and open the gate, but didn't know if he would. It was a confusing explanation. Unsure of what this all would mean, we continued.

![Steep walls]() The steep walls of Quebrada Rurec, some rising for more than a 1000 meters. I'm not into that, but it looked like there were excellent opportunities for big wall rock climbers.

The steep walls of Quebrada Rurec, some rising for more than a 1000 meters. I'm not into that, but it looked like there were excellent opportunities for big wall rock climbers.No barbarians at this gate

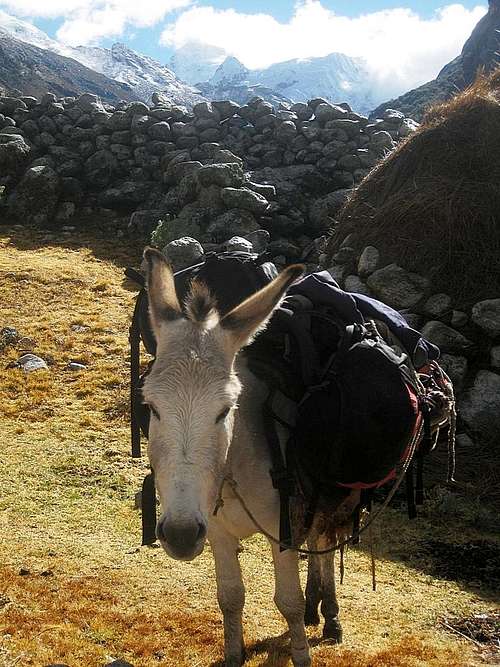

![One of our mules at the wall]() One of our mules at the wall of boulders

One of our mules at the wall of bouldersSure enough, half an hour later we arrived at a solid iron gate. It was locked of course, and there was nobody waiting for us with the key. On either side were big stone walls, spanning almost the whole width of the valley floor – obviously, the gate was erected at a place where the valley was at its narrowest. The only gap in the wall was on the far right, where the river was coming down the valley, with steep rocks on the other side.

The arriero offered to carry our stuff himself, but that was quite ridiculous. I estimate it must have been 50 kilos, if not more. I didn't relish the idea to carry it myself either. If we had intended that, we could have done so from the trailhead.

I wasn't happy, to put it mildly, and I didn't hide it. It wasn't about the prospect of being forced to carry more than planned by ourselves. If some unforeseen event necessitates that, I'll accept it and be flexible. No, it was because we were told about this so late. I felt that the agency should have known and taken care of this, or at least given us the heads up if they couldn't. And, likewise, the arriero should not have told us shortly before arriving at the gate, but at the trailhead. Who knows, maybe we could still have solved the problem there. A phone call to the agency might have told us how and where to get the key. By telling us too late, we didn't have that option anymore.

We studied the gate.

We studied the walls.

We studied the river.

We reckoned we could force the lock of the gate, but there was no way we could get it open without irreparable damage, and we didn't want that. Perhaps if I had taken that burglary 101 class...

The wall we could easily climb ourselves, but mules can't scramble.

The river was too wild to enter.

![Ancient stone work at Machu Picchu]() Ancient stone work at Machu Picchu. It might be frowned upon if we tore down part of this wall.

Ancient stone work at Machu Picchu. It might be frowned upon if we tore down part of this wall.And so we studied the walls more closely. It wasn't masonry, mostly just stacked boulders. Sure, it was sturdy, but a far cry from the fine Inca workmanship that some other parts of Peru are famous for. Pierre and I were looking for weak spots, for a place where it wouldn't be too much work to take down enough it to let the animals through – and repair the damage afterwards; we're no barbarians! The arriero seemed apprehensive at first, but came around to the idea. By the time we had found a reasonable spot and were seriously considering it, our arriero had himself selected a different place, near the river. We followed his suggestion. By the time we had taken down the top half of the wall, he was satisfied we could pass, and with a little persuasion we managed to cajole the mules across.

Until then, he had been riding a horse instead – the first arriero I ever encountered that did that – but now he left it behind. I suppose it was too valuable to risk injury while crossing over the rough lower half of the wall. Mules are a hardier breed.

He said he would go back later to get the key, but frankly, I didn't think it really mattered anymore. We had managed this time around, we would manage again on our way back. Besides, I kind of expected that, near the end of our short expedition, we might have enough time to start the hike out from base camp, and spend the last night near the gate. That would make the final day a short one, giving us plenty of time to get over the wall again. Little did I know yet what that penultimate day would have in store for us...

For some reason, my legs felt like jelly after the delay. I was going a lot slower than before and decided to stick with the mules. In hindsight, an observation about me by Pierre a few days later gave me a clue: although I ate something, I did not drink much. That might have been the cause. Anyway, Pierre was faster and we soon lost sight of him.

Terrain map of Lake Tararhua and the surrounding area. The green paddle points to the small side valley where we located our base camp. The lateral moraine is east of it, between our camp and the lake.

Uruashraju is to the southwest, on the other side of the lake, with the 5600m contour around the summit. In fact, even if you zoom in one more step, no 5700m contour appears. It's a steep summit, and the quality, or, more precisely, the resolution of the underlying digital elevation model just isn't good enough to capture that the summit is well above 5700m. But while the details are missing, you can get a good impression of the overall steepness.

Where is Pierre?

As we neared the head of the valley, the gently rising valley floor gave way to somewhat steeper ground. From the map, I knew lake Tarahua would be up there, on the right hand side of the valley. All we could see though was a big moraine wall blocking it. We went up a zig zag path on its left. It led to a narrower sheltered valley, flanked by steep walls on the left and a lateral moraine on the right. The center was a nice flat grassy meadow, with a couple of tiny streams running through. The arriero asked where I would like to camp. Although I had expected to camp by the lake, this was a beautiful place, and good for the mules too. Two days later we would find out there was a price to pay... But now I'm getting ahead of myself.

Pierre was nowhere to be seen. I walked up the lateral moraine to look for him, thinking he had gone to the lake. On the crest I saw it stretching far down below me, but no Pierre. I blew my emergency whistle to try and draw his attention, but to no avail. Our arriero was shouting too. It must have worked, for eventually I saw Pierre arriving with him.

Our arriero left his mules, then headed back down the valley to try and get the key. With some effort, Pierre managed to persuade him that he would not have to return tomorrow already. Since we would be in high camp anyway, one day later would be fine. But we didn't manage to convince him to first camp for the night and leave tomorrow morning. And so he headed down shortly before nightfall. Probably he would be back at the gate, and, more importantly perhaps, with his horse in just an hour or so. Still, it would be dark by then.

I was finding myself paying increasingly more attention to all the different stoves that my various partners brought, because I had learned that I needed to buy a better one myself. We cooked dinner, using mostly Pierre's. It was a loud and fast MSR, but without a simmer option, only full blast. My own, a Trangia, was almost the total opposite, being quiet and slow but versatile. By now I had learned it was a poor choice for high altitude cooking. But if you ever want to cook

boeuf bourguignon while camping, it's perfect!

![Huantsán and Rurec]() Nevados Huantsán and Rurec form the massive backdrop at the end of the valley

Nevados Huantsán and Rurec form the massive backdrop at the end of the valleyA bungled start

![Uruashraju from the NW, early in the morning]() Uruashraju from base camp, after the clouds disappeared like magic

Uruashraju from base camp, after the clouds disappeared like magicEarly in the morning, the weather wasn't particularly inviting. Even though it was still dark, we could see that the cloud level was low. Not fazed by that, we still got up at 4:30 and went about our business. A little more than an hour later we had eaten breakfast and packed, and all we had left to do before we could leave was to take down the tent. But we didn't. The clouds were still not looking good. Instead, we unpacked our sleeping bags and laid down in our tent to rest some more.

![Clouds swirling around Nevado Rurec]() Clouds swirling around Rurec, seen from were we got on the glacier, not far from to its south face

Clouds swirling around Rurec, seen from were we got on the glacier, not far from to its south faceFortunately, when the sun rose, it soon started to work its magic and surprisingly quickly the clouds started to dissolve. An hour later, it looked much better and we decided to go up after all.

![The edge of the glacier]() The edge of the glacier

The edge of the glacierAt first, the route was obvious and the terrain easy. Pierre soon proved to be much faster than me and went ahead. A while later I found him waiting at a cairn, wondering why I took so long. I knew I was slow today, but couldn't say why. Shortly after the cairn, the terrain was less open and a bit steeper, although nothing serious yet. Occasionally I used a hand, more for convenience than out of necessity. There were cairns all over the place, until we reached the edge of the glacier

[2].

As we unpacked our glacier gear, Pierre discovered he had made an unfortunate mistake at our second start: He had left his food at base camp! It must have happened when we took out our sleeping bags, because he knew it was in his pack when we were about to leave for the first time. It must have gone wrong while packing for second time.

![Nevado Rurec from the south]() Rurec from Uruashraju high camp. If you look closely, you can just see the summit of Huantsán sticking out, right in the middle!

Rurec from Uruashraju high camp. If you look closely, you can just see the summit of Huantsán sticking out, right in the middle!Pierre proposed to camp right there, at the edge of the glacier, so he could make the return trip to base camp and get his food. I didn't think it was necessary, as I believed that I might have just enough food with me for the both of us. I reckoned that Pierre only ate half as much as me anyway and while I might have a bit less to eat, that would be manageable for a day. Besides, I had serious doubts about our chances of reaching the summit tomorrow from there. If eating a bit less was the price to pay, so be it. We decided to continue.

[3]

As soon as we were on the glacier, my legs felt better. We roped up, with Pierre in the lead. Gone was the sluggish feeling I had experienced earlier in the morning and we made good progress ascending the white expanse. Step by step we gained ground on the gentle gradient.

The route doesn't go straight, but curves around a crevasse field. In a good rhythm, we gradually got higher during our wide turn. Eventually, past the crevasses, the glacier flattened out and we reached a ridge. A smaller glacier basin spread out in front of us to the south, and on the other side a high mixed ridge – mostly snow but rocky higher up – stood between us and our objective. It was the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte, the first serious obstacle on the route.

![Cashan from the east]() Nevado Cashan from high camp

Nevado Cashan from high camp

We descended into the basin and didn't waste any time crossing it. Near the base of the mixed ridge there was a bit of a hollow. It was a naturally sheltered place, partially enclosed as it was by the west as well as the northeast ridge of Uruashraju Norte. We couldn't see Uruashraju itself, as the west ridge was in the way, but in other directions, the views were breathtaking, especially of Rurec and Huantsán.

![Uruashraju high camp]() Uruashraju high camp, with the north ridge of Uruashraju Norte in the back and the west ridge to the right

Uruashraju high camp, with the north ridge of Uruashraju Norte in the back and the west ridge to the rightTo the south, the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte blocks our view of Uruashraju itself.Originally, our plan had been to go over the ridge today and camp on the other side. However, with such a fine place, and still not too far from base camp for Pierre to make that food run after all, we decided to camp right there and then.

As Pierre headed down, I started on an early dinner. As I laid out my food, I was surprised to see it wasn't quite as much as I had thought. Without rationing, it would have sufficed until breakfast tomorrow, but probably not much more. There would be little left for snacks and lunch on summit day, and nothing to eat when we would get to high camp. Anyway, since Pierre was getting more food, we would have more than enough, and I could eat to my heart's content.

After cooking, I melted snow until all our water bottles were filled. I made a small protective wall of snow and ice between our tent and the west ridge, just in case some rocks or blocks of ice would decide to come tumbling down our way. Pierre wasn't back yet, so I started exploring the way up the ridge. I figured we could tackle it straight up if we wanted to, which was rather steep and icy, but it was easier to go a bit further west, where the slope was gentler and the glacier was covered with snow instead of ice. Only higher up, below the crest, would it get rocky. But I wasn't even close to that point yet when I saw Pierre entering our small glacier basin again. He had been fast!

After he had eaten as well, we called it an early night.

Terrain map showing the location of our high camp.

Summit day!

Off by the crack of dawn

There would be no alpine start this time. We wanted daylight, so we could see where we were going, especially to see where to descend again on the other side of the ridge once we got on it. We planned to start half past five, which was somewhat before sunrise, but we expected to see something soon enough. We were walking by the crack of dawn, even before the sun was up. It was 5:48. Not bad.

The ridge was higher than it looked. We had to ascend 200m, mostly on the glacier, before we reached the crest. It was not difficult, it just took a bit of time. However, the other side was a much steeper rock slope. No way we would go down there! And so, instead of crossing over the ridge and going down the other side right there, we turned left and ascended along the crest, looking for a way to descend on the other side. It was fun, actually. The ridge was small and rocky, with the odd bit of snow. It didn't rise steeply, but we did need our hands (I estimate the grade to be UIAA II).

| Great views from the top of the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte |

![Uruashraju]() Nevado Uruashraju beckons Nevado Uruashraju beckons | ![The ridge]() View down the ridge View down the ridge | ![Huantsán]() Nevado Huantsán Nevado Huantsán | ![Nevado Huantsán]() Imminent sunrise Imminent sunrise |

![Pierre standing on the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte]() Pierre on the ridge

Pierre on the ridgeWe passed the first steep snow field on the side on our right, but the second one looked promising. It went all the way down and was no more than about 45º steep. The snow was very loose powder. Fine to descend, but I realized it wouldn't be much fun to get back up there again on our return. But we could worry about that later.

As I was climbing down, I approached a small bergschrund. I traversed a bit to the right until I thought I was well beside it before going down any further. Suddenly my legs gave way. My feet had nothing under them, I was hanging on my two ice tools. Pierre held the rope taut as well. I wasn't scared, I trusted my tools and Pierre. If anything, I was surprised how quickly it had happened, and somewhat annoyed at myself for misjudging how far the bergschrund continued below the snow.

I swung my legs over the edge, and got out. Pierre followed me down cautiously. It was not quite as steep from there and we could walk down. Soon we reached the plateau west of the mountain. It wasn't even a 100m below the crest of the ridge. Good, that meant we wouldn't have to climb far on our return.

![The ice fall on the NW face of Uruashraju]() The maze of seracs and crevasses on the northwest face

The maze of seracs and crevasses on the northwest face![A beautiful ramp on Uruashraju]() At the base of the beautiful ramp

At the base of the beautiful rampBoth on the ridge and during our descent to the plateau, we had been studying the slopes of the mountain before us, looking for a way up. The plateau itself was easy, but the steep NW face directly ahead of us was a maze of seracs and crevasses. Far too dangerous, it had to be further right.

And, as if it was made for us, there was a very inviting looking steep but smooth ramp to get us started. The ramp would lead to a ridge, and then an area where, even from a distance, we had seen some big crevasses. A little bit higher still, the mountain looked smoother again, with no obvious dangers between us and the summit. That didn't mean there would not be any, but first we would have to find a way past the big crevasses, or it wouldn't matter one way or the other.

Unlike the powder we had encountered before, the snow on the ramp was hard, providing excellent purchase for our crampons and tools. As we got higher, we reached the crest of the ramp. It was in fact a ridge protruding from the face, and a knife edge one at that! We stayed just below the ridge and continued towards the face itself, and the area where we had seen the crevasses. At that point, our luck changed. We started out on the ramp in bright sun shine, but now that we had reached a tricky spot, the clouds moved in. Visibility had dropped dramatically, to less than 50 meters.

![Poor visibility - continue or turn back?]() Poor visibility - continue or turn back?

Poor visibility - continue or turn back?

Still, there was just one obvious possibility to continue (and one more doubtful looking one). It started by going down a bit, then went across a dubious looking snow bridge.

We discussed our options. Pierre wondered if there would be a point to continue, and, if we did, he had some concern about the descent, especially if visibility would get even worse. I was more optimistic about it, and so I said, pointing to the obvious possibility, "Let's go up this little slope and see what's further on".

That little slope was a steepish traverse (40º), with a big crevasse waiting for us at the bottom should we fall. Slipping was not an option here! But as it was not as steep as the ramp, we were confident that we wouldn't, and while we didn't unrope, we didn't bother to belay either.

Past the traverse, a few dozen meters further, there was again only one obvious way to go on: a snowy ridge. It wasn't wide, but there was some leeway on the left before we would disappear in another crevasse fall in the ‘schrund, and on the right was a descending slope, gently at first, but getting steeper soon, leading to yet another gaping hole. We followed the ridge.

![Pierre belaying me on a steep section]() Pierre belaying me on the crux

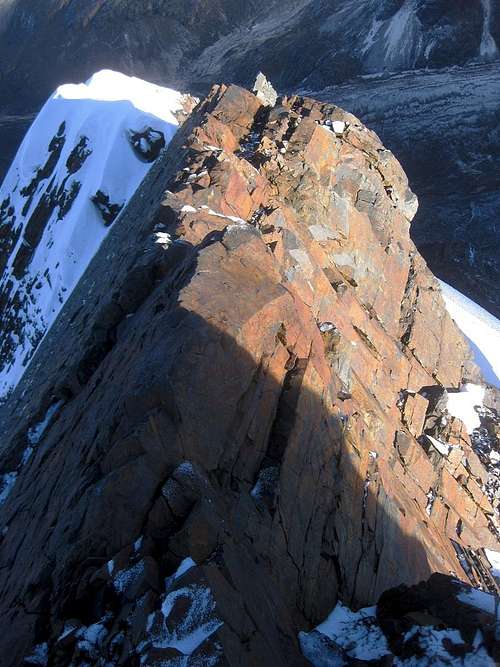

Pierre belaying me on the cruxA few minutes later, we already reached the end of it: Ahead of us was a snow bridge over the crevasse that had been on our left, and across it was a 60º slope. I belayed, Pierre crossed and started going up a short stretch. It was hard and even a bit icy now. Above the the steepest bit, he placed an ice screw to belay me as I followed.

By now, visibility had improved somewhat, and we could see that we could climb quite a long way without any obvious obstacles. The gradient was no more than 60º, mostly less, and the route was in excellent condition: a few centimeters of hard snow on top of ice, making the steepness easier to handle. I could simply place my crampons and tools without having to swing and waste energy.

Higher up, on a flatter section, we crossed one more dangerous looking crevasse. For good measure, we belayed each other again.

Earlier on, Pierre had estimated that we should be on the summit by 11, or turn around if we were not. I had accepted that. Eventually the clock reached 11 – and we were not on the summit. Visibility had dropped somewhat again, so we couldn't see far. However, my altimeter pointed to 5705m – if that was correct, we were almost there! We agreed to continue a little further. If we wouldn't be on the summit very soon, we would call it.

We were on a ridge. It wasn't wide, but it wasn't a knife edge either. It went up very gradually now. Eventually, it didn't rise at all anymore, and then started to go down. We stopped. Is this the true summit? The elevation was right, but in the clouds, we couldn't tell. In all directions, we could only go down, but it still could be just a false summit. There might still be a higher one nearby.

![Pierre and me (with a three month beard) in a whiteout on top of Uruashraju (5722m)]() Pierre and me, with the three month beard, on the summit without a view

Pierre and me, with the three month beard, on the summit without a view

We sat down. One way or another, this was the highest point for us today. There was no wind, and it didn't feel cold. We had a rest. Ate something. Occasionally, visibility improved a little bit, and when it did, there wasn't anything higher appearing around us. At one point we could see far way down the long south ridge, the very last part of which we had ascended. It seemed that we were indeed on the summit!

![Descending Uruashraju]() Descending the crux

Descending the cruxGoing down

The descent took longer than I had expected. We belayed each other again at the crevasse high up, down climbed large sections, and rappelled the steepest part, leaving an ice screw. Carefully we went down the ramp again to finally reach the easier ground of the plateau. Once we crossed it, we were once more at the bottom of the powdery snow slope, which we were not looking forward to. To its right was a mixed couloir, with a dihedral. Would that perhaps be easier? It was impossible to tell. We couldn't see if there were enough irregularities to aid the climbing, so we reluctantly started up the snow instead. It was hard work, as we had expected, sinking away all the time, but slowly we made progress. At the ‘schrund, we belayed each other. Eventually we made it to the top of the ridge again. I was pretty tired, but happy to be up there, since it was only down from there – well, for the next few hours anyway.

During our descent, the clouds had gradually dissolved. Looking back, we could quite clearly see almost our whole route, as well as the summit. Such a pity that it was in clouds precisely during the short period we had been up there...

![Back on the ridge of Uruashraju Norte]() Back on the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte

Back on the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte

Instead of descending on the ridge for a while, we looked for a more direct way back down to our tent. There were several promising alternatives, but we could only see the top part from the ridge. We chose one and started down on the mostly rocky terrain. It almost got us back to the less steep slopes of the glacier below the rocks. With some 10 to 15 meters to go, we reached an exposed section. With crampons, I wasn't confident I could get down there safely. Instead of taking them off, we rappelled.

Shortly before 4 o'clock we were back at our tent. We had taken almost as much time on the descent as on the way up. Tiredness, and especially crossing that last ridge again, had taken its toll and slowed us down.

Since it was already late, there was no time to cook something or even melt snow if we wanted to get off the mountain the same day. We had about 2½ hours of light before it would be totally dark again. Ideally we would be back in base camp by then, but at least off the glacier. Half an hour later, we had packed up everything and were on the move again. Fortunately, it was mostly downhill now, and we made good time. By five o'clock we said goodbye to the glacier.

Since Pierre had more energy left than me, I suggested that he would descend at his own pace. I would follow a bit slower. In hindsight, that turned out to be a mistake. Not a big one, mind you, but a mistake nonetheless. Remember that, at the end of the day, there is a moraine to cross? On his food run, yesterday, he had actually found a trail up that moraine. He explained to me where to find it – but when I got to where I expected the big cairn marking the start, I didn't see it. And so I worked my way up some 100m off trail on rough terrain, while I was already running on vapor.

I kept plodding away, but it seemed to take forever. I wasn't worried, I knew I would get there eventually. The sun disappeared, but I hardly noticed. Slowly but surely I gained ground, and eventually reached the crest.

It was fully dark by now, but route finding wasn't a problem. I knew the area well enough. I figured that I was just a little higher than base camp, so once I had crossed the moraine, I headed down the small valley. The slope was gentle, almost flat even, with some low brushes to go around, but generally easy going. Before long I saw lights in the distance – and at the same time Pierre saw my headlight. He wondered why I was so late? Well, that's what you get for scrambling up a moraine off trail at the end of a long day!

The experience also taught me that camping by the lake would have been better – for humans, that, is, because there wouldn't have been anything to eat for the mules. They would have had to stay further down in the valley.

![Uruashraju route sketch]() From base camp (H) to the summit, with high camp (H) in between. I didn't carry a GPS, so I've drawn it afterwards, based on my notes, photos and memory. I believe it's reasonably accurate.

From base camp (H) to the summit, with high camp (H) in between. I didn't carry a GPS, so I've drawn it afterwards, based on my notes, photos and memory. I believe it's reasonably accurate.![Uruashraju Norte with the west ridge in front]() The razor sharp west ridge of Uruashraju Norte, seen from near Laguna Tararhua on the day after. High camp was on the left and we had to get over this ridge. It was easier than this photo suggests, but in a few years, when that snow high up on the right hand side will be gone, it might be a different matter.

The razor sharp west ridge of Uruashraju Norte, seen from near Laguna Tararhua on the day after. High camp was on the left and we had to get over this ridge. It was easier than this photo suggests, but in a few years, when that snow high up on the right hand side will be gone, it might be a different matter.![Uruashraju NW face, with route outline]() We are on the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte, looking at our objective.

We are on the west ridge of Uruashraju Norte, looking at our objective.

Upon seeing this face, I didn't immediately see how we could get up there. The direct approach is clearly too dangerous, with all those seracs, and too steep as well. The mixed rock and snow ridge on the left also looks well beyond my capabilities. So, we descended to the basin, and when we got closer to the mountain, the ramp on the right turned out to be not quite as steep as it appeared from a distance. The crux would come higher up, at what appears to be about half way up from here.

Much later, when I wanted to reconstruct the route, the satellite views were a massive help: if you know where to look, the ramp could clearly be seen from space, and it's so striking, there simply is nothing else like it. Obviously, in future years the glacier will change, and there is no guarantee that the ramp will still be there.Back to civilization

![A snow covered lupine in Quebrada Rurec]() A snow covered lupine

A snow covered lupine![Our mules in Quebrada Rurec]() Our mules didn't seem to mind the snow

Our mules didn't seem to mind the snowWe didn't plan to get up early, but still woke up spontaneously before six and were walking out by eight. During the night, a fresh sprinkling of snow had dusted the valley, and the sun made it sparkle.

Going downhill it was easy to keep a pretty good pace. Including a break at the gate – although the arriero had the key this time so we didn't have to do any (de)construction work, it was simply a nice and convenient place for it – we covered the 16km to the trailhead in 3½ hours. Our taxi arrived ten minutes later, and quickly we were off to the high life in Huaraz, to enjoy good food and a bit of rest and relaxation in preparation for the next adventure. But that's another story.

The story continues here: Urus Central: To boldly err where no man has erred before

![Uruashraju, with the sun illuminating the route.]() The morning after our climb the weather was excellent. From near our basecamp we could clearly see the final part of our route: up that brightly lit ramp, followed by a short traverse in the shadow to the right and then directly to up the steep slopes, until almost to the top. The final bit is a short and easy ridge to the left - but watch out for those cornices. It actually looks a lot harder from here!

The morning after our climb the weather was excellent. From near our basecamp we could clearly see the final part of our route: up that brightly lit ramp, followed by a short traverse in the shadow to the right and then directly to up the steep slopes, until almost to the top. The final bit is a short and easy ridge to the left - but watch out for those cornices. It actually looks a lot harder from here!Notes

[1] John Biggar: The Andes - A guide for climbers, 3rd edition, 2005. ISBN 0953608727.

[2] The cairns don't mean that Uruashraju is climbed often. There are other, much easier peaks in the area, notably the row of minor summits on the south ridge of Rurec.

[3] If the weather is good or if you are fast, you can climb Uruashraju from the edge of the glacier. In addition, it would be easy to hike out of the valley from there on the day after.

But if we had camped there that day, I don't think we would have made it. As it was, the clouds descended upon us when we were well on our way to the summit, and although we couldn't see far, we were fortunate enough that there really was just one logical way to go, which also proved to be the right one. Had we still been on the plateau before the steep ramp when the clouds descended, I believe we would have turned back.

Comments

Post a Comment