|

|

Area/Range |

|---|---|

|

|

37.69167°N / 119.30833°W |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Trad Climbing, Sport Climbing, Toprope, Bouldering, Ice Climbing, Aid Climbing, Big Wall, Mixed, Scrambling, Canyoneering |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

14494 ft / 4418 m |

|

|

Overview

The Sierra Nevada is the mountain range in California. There are many other beautiful ranges in the state, but none come close to the awesome grandeur of the Sierra Nevada. Home to native Americans, a forbidding barrier to early immigrants, El Dorado to gold seekers, year-round playground in modern times - the range has been all this and much more. John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club, was the first visitor to extol the aesthetic qualities of these mountains, dubbing them the Range of Light. This name, signifying the unique combination of sunny weather, high mountaintops, and colorful alpine meadows found together in this range is still the best short description ever penned for it. Today, the Sierra Nevada sees tens of millions of visitors each year. While sightseeing is undoubtedly the most popular pasttime, many visitors come to enjoy a variety of other recreational activities including skiing, camping, boating, fishing, off-roading, and our favorites - hiking and climbing. Two national parks and 20 Wilderness areas protect the most pristine portions of the range from human development. These allow visitors to enjoy the mountains in much the same fashion as John Muir did some 140 years ago - untrammelled lands, fresh air, clean water, breathtaking scenery.

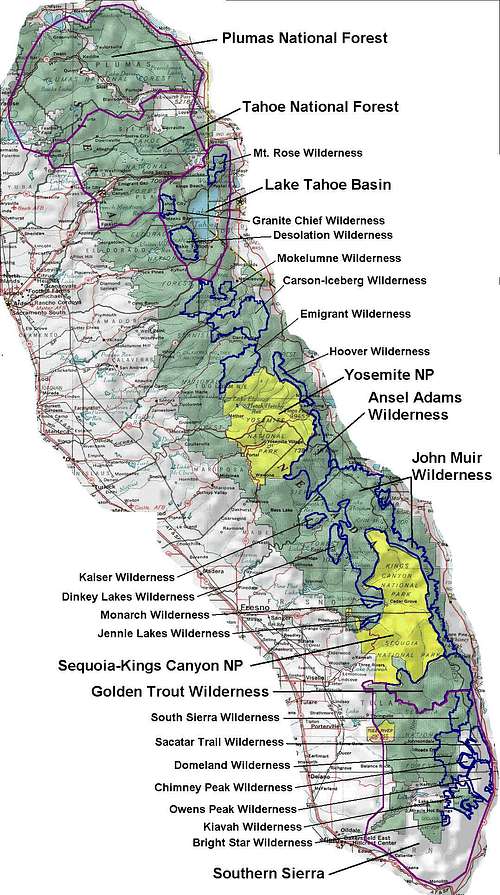

The Sierra Nevada is the mountain range in California. There are many other beautiful ranges in the state, but none come close to the awesome grandeur of the Sierra Nevada. Home to native Americans, a forbidding barrier to early immigrants, El Dorado to gold seekers, year-round playground in modern times - the range has been all this and much more. John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club, was the first visitor to extol the aesthetic qualities of these mountains, dubbing them the Range of Light. This name, signifying the unique combination of sunny weather, high mountaintops, and colorful alpine meadows found together in this range is still the best short description ever penned for it. Today, the Sierra Nevada sees tens of millions of visitors each year. While sightseeing is undoubtedly the most popular pasttime, many visitors come to enjoy a variety of other recreational activities including skiing, camping, boating, fishing, off-roading, and our favorites - hiking and climbing. Two national parks and 20 Wilderness areas protect the most pristine portions of the range from human development. These allow visitors to enjoy the mountains in much the same fashion as John Muir did some 140 years ago - untrammelled lands, fresh air, clean water, breathtaking scenery.The Sierra Nevada runs nearly 400 miles along the eastern edge of the state, varying in width from about 50 miles to 80 miles at its widest. The northern portion of the range is heavily forested with lower elevations - the significant peaks are few and just manage to poke up from the surrounding forests. Starting at the northern end of Lake Tahoe, the peaks begin to rise above 9,000ft and the drama of the Sierra begins to unfold. Ski resorts abound in the popular Lake Tahoe region. The more pristine mountain areas are encompassed within the Mt. Rose, Granite Chief, and Desolation Wildernesses. Between Lake Tahoe and Yosemite National Park the peaks rise higher still, up to about 11,000ft. Volcanic rock dominates this area, making for poor rock climbing opportunities, but scenic hiking and scrambling. Most of the high country in this area is protected within the Mokelumne, Carson-Iceberg, and Emigrant Wildernesses. Starting with the northern boundary of Yosemite NP and extending south to the Golden Trout Wilderness lie the highest peaks in the range, the finest rock climbing, and the most inspiring scenery. Called the High Sierra, this region makes up the heart of the range and its signature attractions - an almost limitless number of peaks and some of the best granite features found anywhere on the continent. Here the eastern escarpment of the range is dramatic, in places rising more than 10,000ft in a few short miles from the Owens Valley below. Many fine peaks above 12,000ft find their home here. Though most have seen some technical rock climbing routes established, the possibilities have even now only been touched on. Comprising the tail end of the range, the Southern Sierra extends to Tehachapi Pass and is a drier, lower elevation region. The peaks in this region are still challenging and the rock climbing opportunites superb. Visitors here are afforded more solitude than found in the more popular areas of the range.

Getting There

There are more than 35 million people that live within a four hours' drive of the Sierra Nevada. Thankfully, not all of them visit the range on a regular basis. But enough of them do that the good folks at CalTrans have seen fit to provide an ample number of ways to get there. This discussion is aimed to the non-residents who aren't already familiar with the road system here and could use an overview on how folks get from the population centers to the Sierra.

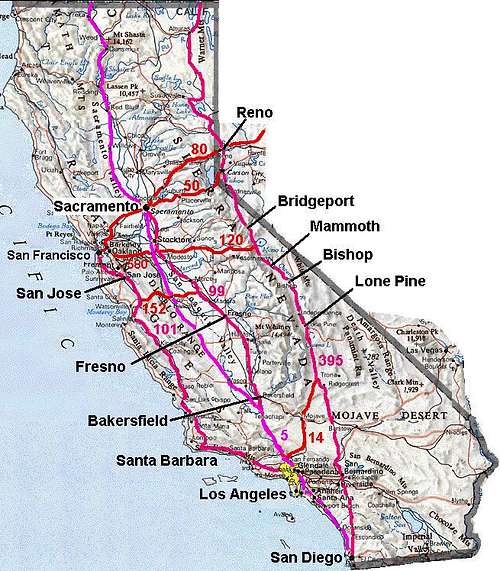

There are more than 35 million people that live within a four hours' drive of the Sierra Nevada. Thankfully, not all of them visit the range on a regular basis. But enough of them do that the good folks at CalTrans have seen fit to provide an ample number of ways to get there. This discussion is aimed to the non-residents who aren't already familiar with the road system here and could use an overview on how folks get from the population centers to the Sierra.The two largest metropolitan areas in the state are the Bay Area (San Francisco/Oakland/San Jose) and the Greater Los Angeles Area. The third largest population center is San Diego, but folks there mostly follow the route taken by those in the southern portions of the LA area. Folks in this southern area generally take US395 straight up to the eastern side of the range. There is a stoplight at Kramer Junction (with SR58) which can create significant traffic congestion at busy times. If coming from the San Fernando Valley or areas thereabouts, SR14 through Mojave and then US395 is the usual route to the east side. Lone Pine takes about 3-4hrs to reach from LA. If travelling to the west side, I5 to US99 is a straight shot north. If heading to the Lake Tahoe region, going up the west side is faster, but the east side is far more scenic. In either case, the drive to Tahoe is a long one, 7-8hrs by the west side, another hour or so on US395. In winter, the east side route is sometimes closed above Bridgeport during snow storms.

From the Bay Area, access is a bit more complicated. Easiest of all to reach is the Tahoe region, a relatively short drive (~3hrs) on I80/US50. I580 is usually used from the North Bay to reach US99 and places south of Lake Tahoe. From the South Bay, SR152 across Pacheco Pass is usually quicker. Both of these routes see high traffic on Friday (outbound) and Sunday (returning) evenings. If trying to reach the east side, the usual route is SR120 through Yosemite during the summer (~5hrs to Mammoth). When SR120 is closed for the winter, access to the east side is much longer, requiring a drive south to SR178 or SR58, or north across US50 or SR88 to US395 and then south. As this can take 8hrs or more, only the hardiest of weekend warriors will make this gruelling winter pilgrimage.

Most of the remaining population centers in the state are in cities along US99, having obvious access to the Sierra. The two most populated regions just outside the state are found in Las Vegas and Reno. The latter sits right on US395, while residents of Las Vegas will have a longer drive (~5hrs), crossing Death Valley via SR190.

Access

A wide variety of roads provide visitor access to the Sierra Nevada. US395, perhaps one of the most beautiful routes in the state, runs the entire length of the range on its eastern edge. US99, in far less dramatic fashion, does similarly on the western edge. In the north, SR36, SR70, and SR49 cross the range roughly west to east. SR89 bisects the range vertically from Lake Tahoe northward to Lassen Volcanic NP. In the Tahoe region, I80, US50, and SR88 cross the range from west to east. All of the above mentioned routes are open year-round, with occasional closures during heavy storms until plows are able to clear the roads. South of the Tahoe area, SR4 and SR108 provide access across the range via Ebbetts and Sonora Passes, but these are closed in the winter months. Plowing on SR4 is done only as far east as Lake Alpine near Mt. Reba, while SR 108 is plowed only to the town of Strawberry near Dodge Ridge. SR120 across Tioga Pass in Yosemite provides the only east-west crossing in the High Sierra region and is also closed in winter. In the Southern Sierra, SR178 heads across Walker Pass while SR58 goes across Tehachapi Pass, both kept open year-round though SR178 sometimes closes due to rockfall.

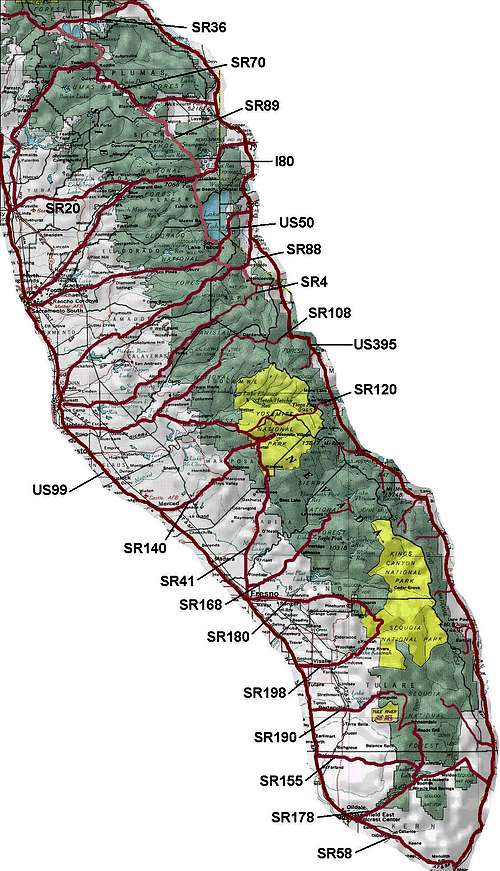

A wide variety of roads provide visitor access to the Sierra Nevada. US395, perhaps one of the most beautiful routes in the state, runs the entire length of the range on its eastern edge. US99, in far less dramatic fashion, does similarly on the western edge. In the north, SR36, SR70, and SR49 cross the range roughly west to east. SR89 bisects the range vertically from Lake Tahoe northward to Lassen Volcanic NP. In the Tahoe region, I80, US50, and SR88 cross the range from west to east. All of the above mentioned routes are open year-round, with occasional closures during heavy storms until plows are able to clear the roads. South of the Tahoe area, SR4 and SR108 provide access across the range via Ebbetts and Sonora Passes, but these are closed in the winter months. Plowing on SR4 is done only as far east as Lake Alpine near Mt. Reba, while SR 108 is plowed only to the town of Strawberry near Dodge Ridge. SR120 across Tioga Pass in Yosemite provides the only east-west crossing in the High Sierra region and is also closed in winter. In the Southern Sierra, SR178 heads across Walker Pass while SR58 goes across Tehachapi Pass, both kept open year-round though SR178 sometimes closes due to rockfall.In addition to the major roads listed above, a variety of other roads provide partial access to the range from both the west and east sides. On the west side, SR140 and SR41 provide access to Yosemite as far east as Yosemite Valley. SR168 provides access to Lake Thomas Edison and Florence Lake (between Yosemite and SEKI NPs), though in winter it is closed past Huntington Lake. SR180 and SR198 service western approaches to Sequoia-Kings Canyon NP (SR180 to Cedar Grove is closed in winter). SR190 and SR155 provide additional access to Southern Sierra from the west side. On the east side, there are many roads leading to trailheads on the steep escarpment, most of which are closed in winter.

More on Sierra Nevada Highways from sierranevadaphotos.com

Get current road conditions from CalTrans

Geology

The geology of the Sierra Range is complex, formed by a combination of volcanic activity, plate tectonics, and glacial erosion. In the days of the dinosaurs, the Sierra was coursed by a chain of volcanoes similar to the present day Cascade region. Much magma flowed out to the surface as lava through these intrusions, while even more solidified deep underground amidst immense pressures to form the characteristic gray-white granite that is ubiquitous to the range. Over time, erosion scoured off much of the weaker volcanic rock above the granite, revealing domes and the widespread granite batholith that extends the length of the range. Less than five million years ago the Sierra Nevada began to rise as the Pacific plate pushed under the North American plate. The subduction created a massive tilted fault along the eastern edge of the range, raising the Sierra and sinking the land to the east. This process is ongoing, raising the elevation of the range yet higher with each slippage of the fault which we experience as earthquakes in this region.

In geologically recent times, the Pleistocene Ice Age brought significant glaciation to the range. Rivers of ice carved out their former stream channels and created the sheer walls and hanging valleys found in Hetch-Hetchy, Yosemite Valley, and Kings Canyon. As they retreated, the glaciers clung tenaciously to the north facing slopes of the higher peaks, fracturing and forming the steep north faces found on many of them. The glaciers that remain in the Sierra are but the remnants of this colder clime. Doing very little mountain carving in this day and age, most Sierra glaciers sit quietly in the shadows of the north faces, biding their time until the next Ice Age emerges.

Learn more from the USGS and the Yosemite & SEKI NPS sites

In geologically recent times, the Pleistocene Ice Age brought significant glaciation to the range. Rivers of ice carved out their former stream channels and created the sheer walls and hanging valleys found in Hetch-Hetchy, Yosemite Valley, and Kings Canyon. As they retreated, the glaciers clung tenaciously to the north facing slopes of the higher peaks, fracturing and forming the steep north faces found on many of them. The glaciers that remain in the Sierra are but the remnants of this colder clime. Doing very little mountain carving in this day and age, most Sierra glaciers sit quietly in the shadows of the north faces, biding their time until the next Ice Age emerges.

Learn more from the USGS and the Yosemite & SEKI NPS sites