Foreword

![Post Injury Agony]() Agony immediately post injury.

Agony immediately post injury. |

Sunday, October 21, at about 12.15pm. The group is climbing steep but routine terrain. Without warning, without a slip or a misstep, pain like a knife blade in my left knee and I collapse in agony on the ground.

This had happened to me before so I knew immediately what was wrong. I’d torn my medial meniscus. I couldn’t walk; I could barely even stand. Based on previous experience I knew I was going to need surgery.

Just another case of Murphy’s law? Rather more than that I’m afraid. This particular dose of

merde had chosen to make itself manifest at 4,300 metres halfway up to one of the most remote passes in the Himalaya, almost five days travel from the nearest village over some 5,500 metres of total ascent. There was no running away from the fact that this was a serious situation.

If we thought, however, that this was the limit of the day’s bad news, we were soon to be proven horribly wrong.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me take you back to the beginning and tell you the whole story properly.

Introduction

My old university friend Tony regularly organizes trips in Nepal that try to stay as far from the tourist routes as possible. The principal objective of his latest trip was Thorong Ri, a 6,000+ metres peak above the high pass, the Thorong La, on the Annapurna circuit. Not for us though the standard approaches from Jomosom or Besisahar. Oh, no, we’re much tougher than that. We would start from the tropical village of Khadarjung and make our way northeast over seldom traveled cowherd tracks or old trade routes which run roughly parallel, and to the south of the massifs of which Machhapuchhare and Lamjung Himal are the principal summits. Roughly a week’s travel, gradually gaining altitude, would get us to the valley of the Miyardi Khola from where we would access the Namun Bhanjyang. The Namun is a high (5,560 metres) and difficult pass formerly used for migration and trade between Tibet and the Gurung (Ghurka) Nepalis of the region but now virtually unused by anyone other than the occasional trekking party. Once across the Namun, a long 1-2 day descent would put us on the tourist path at Timang and it would all be plain sailing from there.

![The Namun Bhanjyang]() The Namun Bhanjyang.

The Namun Bhanjyang.

Whichever way you look at it, it all looked like a damned good trip to me. So I duly signed up along with Alan, John, Rob and Taylor from the London Mountaineering Club, Mark from Midland, Michigan and, of course, our leader Tony.

A local Kathmandu company,

High Country Trekking, organised all the permits, transfers, porter hire etc. We had 20 or so porters led by Chandra, a kitchen staff of 5 headed by Birkha Tamang our cook, Krishna Tamang our trekking guide and, last but by no means least, Taschi and Phanden our climbing Sherpas. Phanden, as Sirdar, ran the whole thing. Like all good leaders, he did so by dint of experience – both he and Taschi are three-time Everest summiters – and by example, as we would find out.

Victoria to Kathmandu

It’s a long convoluted way from Vancouver Island to Nepal. I left home on the evening of October 7th and after the obligatory overnight in Bangkok didn’t reach Kathmandu until the 10th.

No rest for the wicked though. My wife is her own one-woman NGO as far as Nepal is concerned. Word of the arrival of her proxy had preceded me and a succession of visitors soon began to arrive at my hotel, all enquiring after the whereabouts and health of “Gwen didi”. She sends clothes and equipment here, she sponsors kids in vocational school in Kathmandu, she has a special interest in

the school in Thamo (between Namche and Thame) that has been already described on SP and the list keeps growing. This time even before MY trip started, I had to organize the transport of new shoes for the Thamo school English teacher and wart treatment for the kids there, as well as meet the headmaster of the vocational school in Kathmandu (and pay the kids annual fees). All this is accompanied by endless cups of tea and other obligatory social niceties, so it was quite a relief when the rest of the group arrived on the 13th and we could actually go trekking.

Rain and Leeches

![Porters Packing]() Porters packing

Porters packing![Start Valley]() Start valley

Start valley![Approaching Ghalageon]() Ghalageon

Ghalageon![Jukka !!]() Leeches!!

Leeches!!![Descending to Parje]() Descending to Parje

Descending to Parje![Descending to Parje]() After the storm

After the storm

On October 15th we took an early flight to Pokhara and, after breakfast there and a stroll around town, were soon off to the start of our route only a half hours drive up the valley of the Seti Khola to somewhere in the neighborhood of the village of Khadarjung at an altitude of about 1,100 metres.

Because of Yeti Airlines’ restriction on baggage weight, our luggage had gone from Kathmandu to Pokhara by bus a couple of days earlier and there were our porters busy lashing it all together into the mountainous loads that they are accustomed to carry. For those of us who have seen this before, it’s still a humbling experience to see these guys carry the tremendous weights that they do. The “Himalayan virgins” in the group just stood aghast with expressions somewhere between awe and guilt.

Our afternoon was a pleasant stroll in warm sunshine along well-trodden paths up the east side of the valley of the Sardi Kola to the village of Ghalageon where the enterprising locals greeted us with beer and Pringles.

At these low altitudes and with lots of cows and other targets around, it didn’t take long for the genus

Haemopis to make its appearance. The Himalayan variety of leech – or “jukka” - in these regions isn’t as bad as other places I’ve seen them – in the rainforest of New South Wales for instance – but they’re bad enough. An idyllic first night campsite was soon ringing to yells and shrieks as the little buggers began to crawl over boots and up legs. Dinner in the mess tent was punctuated by constant boot checks – yes there they were – and a competition to see who’d get the most bites. Mark won it hands down on this and every night after. I’d learnt in Australia that the thing to do is to spray your inner socks liberally with deet. I’d brought my own supply with me and it worked a treat. Not a single bite. Taylor bought some locally under the absolutely marvellous trade name “Wack Off” and it worked similarly well for her. Poor Mark tried both and got bitten anyway.

A peaceful night was interrupted about 2am, when everything lit up like it was noon and the first crash of thunder woke me up with a start. The heavens soon opened and the rain came pouring down. If you’re going to tackle the jungles of the lower slopes of the Himalaya and if you want to maximize the “jukka experience” in the process, then you might as well do it in a downpour. I got my gear re-organised for a wet weather day and went back to sleep.

It was leech Nirvana as we packed up the wet tents and left at about eight the next morning in pouring rain. Initial sniggers at Rob’s and my umbrellas were soon muted as the steady rain began to find chinks in everyone’s gortex armour. Starting at 1,850 metres we made our way mostly east up cowherd tracks through the jungle to a high point of 2,650 metres before beginning a long descent towards Parje, Siklis and the valley of the Madi Kola. This was mostly a head-down plod watching the scores of jukka waving about trying to find an attach point. In fact, we needn’t have worried. They were just using most of us for practice before leaping aboard Mark across huge distances. At about 12.30 a cowherd shelter provided somewhere dry for one of Birkha’s splendid hot lunches and enabled the porters to catch up. They’d had a hard time of it that morning in steep, slippery conditions and, of course, so early in the trek, load weights were at their maximum.

It was a lot of map distance and a long 635 metres descent to Parje that afternoon. At least the sun came out late in the day and provided us with the first views of Lamjung Himal dominating, as it would for the next 3 or 4 days, the skyline to the northeast. We arrived in Parje by headlight at 6.45pm. Phanden then collected all of our lights and went back to help the porters down. As soon as the western members were safe, his thoughts turned immediately to his crew. The last porter only came in at about 9pm. It had been a long, tough day and we weren’t even into the mountains proper yet.

From The Tropics to The Alpine

![Lamjung Himal from Siklis]() Lamjung Himal from Siklis

Lamjung Himal from Siklis

Idyllic conditions greeted us the next morning. Sunny with the night chill already beginning to recede as early as 6am and with Lamjung towering above our camp.

We bade Parje farewell at about 8 and, after a stop for photos in Siklis, the main Gurung village in the region, we began the 650 metres descent to the river crossing at the confluence of the Madi and Gnach Kholas, followed by the 950 metres climb up the ridge between the two rivers to the only viable campsite en route.

![The Gnach Khola Gorge]() The Gnach Khola gorge

The Gnach Khola gorge![Crossing the Gnach Khola]() Crossing the Gnach Khola

Crossing the Gnach Khola

On the way down to Parje the previous evening, we’d noted that all the villages in view were obviously supplied with electricity. The source for this is a hydroelectric generating station on the Gnach Khola. It’s a simple but interesting affair and obviously does an excellent job for the valley. A rickety bridge gave access to the station and our onward route. At the level of the river, we were only marginally above our starting altitude and in a steamy and tropical environment.

The afternoon was a bit toilsome as we laboured up the ridge in the sun but we eventually emerged onto what was quite clearly a cow pasture at about 2,400 metres at just after 4pm. John immediately named the place “Cowpat Camp”. Once again the porters had some trouble with the route and, once again, the last ones came in by headlamp.

Every western member on the expedition had a duty over and above simply being out there and walking. Mine was first aid officer. I’d already patched up several members’ cuts, scrapes (including my own) and leech bites but now I received my first porter “patient”. The poor lad had severely swollen tendons above the knee and was in obvious discomfort. I dosed him liberally with “vitamin I”, fitted him out with a tensor bandage and thought it 95% sure that he’d be going down in the morning. Which is precisely what transpired.

“Cowpat” didn’t have an awful lot to recommend it. But what it did have were glimpses of Machhapuchhare and Lamjung framed in the trees on the edge of the pasture where the ridge dropped off. That evening we were treated to both in excellent alpenglow light. Even at this distance we could hear the boom of avalanches peeling off the south aspect of Lamjung.

![Machhapuchhare]() Machhapuchhare

Machhapuchhare | ![Lamjung Himal in Alpenglow]() Lamjung Himal in alpenglow

Lamjung Himal in alpenglow |

Once the sun went down, it got damp and cold very quickly and, after dinner, we were soon in bed. Jukka activity was now noticeably muted compared to yesterday.

![Forested Ridge]() Climbing the ridge

Climbing the ridge![Forested Ridge]() Break in the trees

Break in the trees

We had at this juncture been joined on the route by two Indian gentlemen and their crew. They were also aiming to cross the Namun but to return directly to Besisahar from the other side. They seemed rather miffed that we were there, declined to speak to us very much and rather pointedly pitched their camps as far away from us as they could. They were also moving

very slowly.

Onwards and upwards from Cowpat the route ran always northeast from semi-tropical to high bamboo forest and eventually to rhododendron forest. The only place to go was up the ridge and the next possible flat place to camp with water was on a high summer grazing pasture 1,200 metres above us. In fact this was the

only water available anywhere that day. If you didn’t carry it from Cowpat, you didn’t get to drink. However, map distance was relatively short and, after an 8am start and a good break for lunch, we arrived tired but not exhausted shortly after 2pm with the porters thankfully not far behind. For the first time in 4 days, the tents went up before dark and had a reasonable chance to dry. We had an afternoon to relax, dry what gear we could and generally re-fuel after 4 long days. The terrain was now open and decidedly sub-alpine. Lamjung Himal was hidden by the continuation of the ridge above us but the continuous thunder of avalanches let us all know it was there.

The sun went behind the ridge about five and the mercury promptly fell out of the bottom of the thermometer. By 5.30 my damp tent was covered in a layer of ice and out came the down jacket. Balmy climes were now behind us. As I knew from experience, when the sun was gone, it was going to be unrelentingly cold. Birkha outdid himself with an excellent Chowmein for supper and I retired to my frigid nylon palace by 8.

![Enlarge]() Approximately 200° panorama from Machhapuchhare to Lamjung Himal Approximately 200° panorama from Machhapuchhare to Lamjung Himal |

![<i>En Route</i> to Camp 5]() En route to camp 5

En route to camp 5![Porters <i>en route</i> to Camp 5]() Porters taking a break

Porters taking a break

Compensation for a cold night arrived the next morning with the sun but mainly after re-attaining the ridge just a few minutes above camp. A spectacular and uninterrupted panorama from Machhapuchhare to Lamjung Himal and everything in between. We had this visual feast constantly in view as we contoured the grassy ridge east for a couple of hours before turning northeast once more and into a high valley which looked from this aspect like a cul-de-sac. Gradually gaining height on the west side of this valley we could eventually make out an exit on the right (northeast) side. Our route took us almost to the back of the valley and we pitched camp on snow by a small lake at 4,000 metres. After a sunny morning, it had now become quite cold and began to snow lightly.

Just down the valley from the lake was the inevitable herdsman’s hut and quite close to it the remains of a snowman. We paid this little mind at the time but later began to think of the snowman as a vital clue in what transpired later.

![Approaching Camp 5]() Approaching camp 5. The "snowman" can be seen as a white dot just to left of centre.

Approaching camp 5. The "snowman" can be seen as a white dot just to left of centre.The Death March

![View back to Lake Camp]() View back to Lake Camp

View back to Lake Camp![The Unnamed Pass]() The unnamed pass

The unnamed pass![Approaching the Unnamed Pass]() Approaching the unnamed pass

Approaching the unnamed pass![On the Unnamed Pass]() On the unnamed pass

On the unnamed pass![The Long Traverse]() The long traverse

The long traverse![Porters descending to the Miyardi Khola]() Porters descending

Porters descending

I don’t know which member of the expedition came up with this name but it certainly described the day accurately and was almost prescient in terms of what came later.

Our objective for the day was the Namun La base camp in the valley of the Miyardi Khola at about 4,000 metres – almost exactly the level we started. In between, however, was an un-named 4,500 metres pass that connected the valleys. There would be no water on the route other than what we carried from camp or obtained by melting snow.

We left the lake camp at 7.45 in cold, clear conditions and were soon climbing snow slopes towards an obvious shoulder that led out of our present valley.

Surprisingly, although by now we had reached a fairly remote spot, why was the trail, such as it was, strewn everywhere with paper garbage? And some of it looking remarkably fresh. To be sure there were still cowherd huts and other structures at almost every open spot but we’re still talking just a handful of folk ever coming this way.

By 10 am we had the pass in sight and were traversing a shallow bowl in blistering sun. Insufficient fluid intake and unaccustomed altitude had most of us in various degrees of pain during this phase.

By 1.15 we had summited the pass. Our efforts were rewarded by cloud, mist and light snow. Views back or ahead were now severely limited.

The day earned its name, however, by what followed. A long, long traverse at 4,500 metres, around the shoulder of the mountain to the head of the pass that gave access to the Miyardi Khola. By the time we had our objective in view it was getting on for 5 pm and the snow slopes down to the river had already turned icy and dangerous.

Everyone carefully inched their way down, heel-booting in and helping the porters whenever and wherever we could. Always leading by example, Phanden even took a porter-load from one kid who was having particular problems. As it was, we didn’t get down to flat terrain until almost 6 and the last porters over an hour later. Once again we surrendered our headlights as Phanden, Taschi, Chandra and Krishna brought the porters safely into camp.

Compensation for dehydration and tiredness was all around. The usual afternoon cloud had cleared during the descent from the pass and before it got dark we were treated to stupendous views of Manaslu and Peak 29 to the east and the Namun La across the river to our north. It looked difficult but not impossible. I did wonder, however, how we were going to get the porters over it.

![Approaching the Miyardi Khola Valley]() Approaching the Miyardi Khola valley in fading light

Approaching the Miyardi Khola valley in fading lightInjury, Tragedy and Crisis

After the long day yesterday, we got up an hour later at 7 after the sun was on the tents. It was such a fine morning that we had breakfast in the sun outside the mess tent feasting on the views of Manaslu. We were camped at an interesting and historical spot. This was where Tibetans and Gurungs would meet to trade when the former came over the Namun with their salt and other goods. There was a stone hut there but this probably dated from more modern times.

![Camp at The Old Trading Area]() Camp 6 at the old trading area

Camp 6 at the old trading area

Such a perfect start to what ended as anything other than a perfect day.

![View west from Camp 6]() West from camp 6

West from camp 6![The Miyardi Khola Gorge]() The Miyardi Khola gorge

The Miyardi Khola gorge![Crossing the Miyardi Khola]() Crossing the Miyardi Khola

Crossing the Miyardi Khola![The Key to The Namun La]() The key to the Namun La

The key to the Namun La![View South Approaching the Namun La]() View back to the Miyardi Khola

View back to the Miyardi Khola![Initial Retreat]() Initial retreat

Initial retreat![Injury Site]() Injury site

Injury site The first hint of problems on the horizon was Hari Tamang, one of the younger porters. Phanden brought him to me with “sore ankles”. “Sore” turned out to be a ring of suppurating sores encircling his lower legs and causing him considerable pain. I’d never seen anything like it before. My first thought was some kind of parasitical infection picked up during the lower marches. Antibiotics administered by a westerner were not an option – we couldn’t risk an allergic reaction. So I cleaned the area with disinfected water, treated it with iodine and isolated it with breathable dressings. I was not at all convinced that this would achieve anything. This guy needed to be evacuated. The quickest way out, however, lay over the pass ahead of us.

We moved off from camp at 9.15, initially west before turning north down the steep, eroded sides of the Miyardi Khola. The river at this point is braided and each branch is fast flowing but we were soon across with minimum difficulty and continued north directly towards the sheer cliffs that guard the Namun. As we got closer the route up revealed itself as a steep but eminently do-able ramp right under the cliffs. After a brief break at the bottom of the ramp, we headed up at about noon. The kitchen staff had gone on ahead and the porters were strung out behind us.

Fifteen minutes up-slope and for no apparent reason, my knee collapsed. I was in agony. I could bear no weight whatsoever. I was, in short, helpless. The crisis was upon us.

Tony’s reaction was immediate and effective. Stop all movement on the mountain. Send someone up to bring the kitchen staff down. Get me down to somewhere horizontal. Set up a camp. In general, consolidate our position and ensure everyone’s safety.

This was all relatively easily achieved except for moving me. However, even this was accomplished after an excruciating 15 minutes being piggy-backed down steep snow by Phanden and Taschi in turn. Somehow we found room for all the tents on various degrees of slope and took stock.

We were at least 5 days away from the nearest village.

The Indian group had already turned back and it was unlikely in the extreme that anyone else would come this way.

We were not carrying a satellite phone but Phanden had a cellular phone that he had been able to use from the lake camp 2 days before.

We had 5 days supply of food left. Easily enough to cross the Namun and pick up supplies on the other side, as originally planned, but barely enough to reverse our outward route.

It was decided that Phanden would leave immediately for the summit of the Namun and determine if he could get cellular service from there. If so he would summon a helicopter to evacuate me as well as Hari. If only things had been that simple....

We watched Phanden climb up towards the cloud but then stop for a long conversation with Birkha who was on the way down. The reason for this became apparent as soon as Birkha reached us. The kitchen staff hadn’t in fact received the instructions to come down. They’d turned round of their own volition. The rainstorm we had endured 5 days ago had fallen on the Namun as impassable levels of snow. But there was worse – much worse. There was a body on the route! A recent death. Birkha was far too upset to be that rational, so we just prayed that he was mistaken.

When Phanden returned several hours later, however, we had to accept the truth. Someone – a Nepali – had died just a few hundred metres above us. He was “buried” under stones. Another group had preceded us, had been caught in desperate conditions and one member had succumbed to the elements. Suddenly the fresh garbage on the trail and the snowman below lake camp began to take on extra significance.

As devastated as we were by this discovery, we forced ourselves to focus on the fact that we had a crisis of our own to manage. There was no prospect of crossing the pass. Neither had Phanden had been able to get a signal from the highest point he was able to reach. He was confident, however, that travelling light and fast, he could go down as far as the lake camp, make the call for a helicopter and return to where we were in a day. There really wasn’t any option.

Marooned

Phanden had already left before any of us were awake the next day. My knee was excruciatingly painful. All I could do was lie in my tent or suffer the humiliation of having to be carried to the latrine or anywhere else for that matter.

I was also desperately worried about Hari. I was no longer able to get out to look after him and his sores needed re-dressing. Fortunately, Mark volunteered to take over my duties in this respect even though he’d had no formal first-aid training. So they both came to my tent and I showed Mark what to do and explained the necessity of breathable dressings. Between us, we would manage Hari’s and others’ injuries this way for the rest of the expedition.

![Hari s Ailment]() Hari's ailment

Hari's ailment

After breakfast the whole group, along with Krishna and Taschi went off to prospect for a landing site for a helicopter. They duly returned with the good news that they’d found, marked and cleared a site but that it was 200 vertical metres below and that I’d have to be carried down there.

This time, the Sherpas rigged up a sling on the same kind of tump-line that they use to carry loads and hauled me down there with the minimum of fuss and without any discomfort. Krishna took the last shift and while he was still carrying me I noticed that he had a bootlace undone – so rather than have him trip, I told him about it. With me on his back he just bent over and did it up. Krishna is about five foot four or five tall and all of 110 lbs!!

Again we set up camp wherever we could find flat spots close to the landing platform. Phanden returned just before dark. He’d contacted Ang Rita, the owner of High Country and the helicopter would arrive at 7 in the morning. He’d even spoken to the pilot. The nightmare was nearly over. The group began to make alternate plans for the remaining time following my evacuation and we all went to bed, if not happy, then content at least that we’d managed a potentially bad situation as well as possible.

With the pressure off, or at least reduced, thoughts again turned to the body on the pass and speculation as to what had happened was soon rife. Then, as now, we came up with no answers.

The morning dawned cold and clear. I was up at 5 to begin the slow business of packing my gear and had already crawled and hopped out to the mess tent by the time Krishna appeared at 6 with morning tea. Seven o’clock soon came around. Goodbyes were said, last photos were taken, my gear stood ready and we waited. And waited. And waited. By 11am the usual clouds rolled in, visibility went to near zero and it was obvious that rescue was not, after all, at hand. We made relative light of it – poor flying conditions from Kathmandu of course. Ang Rita will be moving heaven and earth by now. They’ll definitely come tomorrow. But I could see Tony and Phanden in deep conversation.

Here was the quandary. What if suitable flying conditions never came about? Every day spent waiting was one more day of food consumed. At some point there would have to be snowstorm. Hadn’t there been a deadly one already? Every day spent waiting in clear weather was one day closer to a storm. What if we had to get out by ourselves? We would already have to ration food if we had to go all the way back to Siklis. Phanden was all for starting on this the next day but Tony counseled patience. In the end it was agreed that we would wait where we were for the helicopter and that if none appeared in the morning, we would make the short trip across the Miyardi Khola to our previous camp at the old trading area and wait one more night there.

Already, however, thoughts were turning to the hard fact they we might simply have to manage the situation without outside help. Plans were already afoot, therefore, to devise the most feasible escape route. Yes, we could simply reverse the outward route as far as Siklis and re-supply there. But Chandra was confident that a route was possible along the high ground that ran east above and to the south of the Miyardi Khola and then south along high ridges before a descent of some 3,000 metres would become possible to the tourist path in the neighbourhood of Syange. He thought this would take us 2 days to cover. It was decided that in addition to the group moving across the river, Chandra, two porters and Krishna would go ahead and explore Chandra’s escape option. We would need at least one place to camp en route. If they found something Krishna would return from there while Chandra and the porters would push on if they thought that the route continued to be viable. Once down to the tourist path, Chandra would seek help while the porters came back with the extra food we needed.

Food and medical supplies were running very low. We knew we were pushing our luck with the weather. The pressure was back on in full force. The option of a two versus five day escape plan was an easy sell for all of us.

Morning again dawned clear and, again, no helicopter appeared. Dismay was evident on everyone’s faces. Mark and I re-dressed Hari’s sores. They were visibly worse. This was a battle we were slowly losing. Any worse and we might have to risk giving him antibiotics. By now Mark had effectively adopted Hari and his concern was palpable.

![Retreat across the Miyardi Khola]() Retreat across the Miyardi Khola.

Retreat across the Miyardi Khola.![Morning View West from Camp 6]() Morning view east from camp 6

Morning view east from camp 6

By 9 am we’d packed up and were ready to move. Carrying me was now a serious prospect. This phase would be short but the ground down to and across the river was serious. Three porters – Jitman Tamang, Lama Tamang and Ningma Sherpa - volunteered to carry me and Phanden, Taschi and Krishna would also share the task. Any fears I had that they wouldn’t be able to take my weight or might drop me on tricky ground were allayed within minutes. I could feel the heart of whoever was carrying me almost beating out of his chest – and yet their main concern was, was I comfortable enough? Was I OK? Did I need anything? What selflessness, what courage, what strength. I was deeply and unalterably humbled. And, although I didn’t yet know it, I hadn’t seen the half of it to this point. One thing I did know though. If it became necessary, these guys REALLY could carry me out of there.

Camp at the old trading area with all that flat ground felt positively luxurious. A small bluff above camp provided some rock climbing diversion to help pass the time. But it was a cold, cloudy afternoon and I soon crept into my tent thinking anxiously about the crucial days ahead.

Krishna returned about 4pm. The route was viable as far as he had gone and looked to continue beyond there. Chandra and the porters had gone on from the point where they had found open ground and water. The gist of Krishna’s comments was that the first two hours were on snow and then the route mellowed out.

![Double Lenticular over Manaslu]() Double lenticular cloud over Manaslu

Double lenticular cloud over Manaslu | ![Merged Lenticular over Manaslu]() Merged lenticular cloud over Manaslu

Merged lenticular cloud over Manaslu |

Another crystal clear morning dawned with stunning views of lenticular clouds forming around the summits of Manaslu and Peak 29. But no helicopter. By 8.30am we were packed and ready to go. Lama walked up to me twirling the carrying sling round his head. “Lama helicopter” he said. We dissolved in laughter.

At 8.40 we walked out of camp and committed to Chandra’s route.

The Escape Route

The path made by Krishna

et al the previous day led east from camp. A pleasant stroll at first by a lake and up a mellow rise. The carrying crew were laughing and joking and hardly changing over at all. It was also quite obvious that this was a major route. In the few spots where the snow had melted a beaten path was evident.

Once over the first rise, however, and things changed rapidly. The route continued up steeply and the river gorge below began to offer some considerable exposure. The “helicopter boys” now had to change frequently as the grade steepened and the laughing and joking became considerably muted. It stopped completely when we topped out on this section and looked ahead. Before us was a steep snow filled cirque around which we would have to traverse to reach the ridge crest ahead. I avoided looking at my companions but I could already feel the thoughts forming. “How the hell are we going to do this”? Honestly said, it looked hard enough just to walk around, never mind carrying 160lb on your back.

![The Escape Crux]() The escape crux

The escape crux![Leaving Camp 6]() Beginning the escape

Beginning the escape![Start of The Crux]() Start of the crux

Start of the crux![Crux of The Escape Route]() The crux of the escape

The crux of the escape![Escape Crux]() Almost there

Almost there![Across The High Ridge]() Along the high ridge

Along the high ridge![Mid Point on The High Ridge]() Mid point of the high ridge

Mid point of the high ridge

Phanden and Taschi assumed the duties on this section. One carried and one cleared and cut steps in the snow and ice. I just tried not to look. They inched along one step at a time, were over the difficult section in about 10 minutes and grunted up to the high point at about 4,300 metres 10 minutes after that. At no time did I feel unsafe. The guys made not a single slip and, once again, were more concerned about me than about themselves. Once on safe ground Phanden and I shook hands silently. Phanden, because he was out of breath. Me, because I couldn’t trust myself to speak. It was an emotional, draining experience.

We were no more than 2 minutes below this high point when everyone heard the sound of a distant helicopter. Certainly below us but no one could tell from which direction. No matter. It never materialized and could probably not have extracted anyone from this spot if it had. We went on.

Guided by Krishna, we were off snow an hour later and found ourselves on the expected high ridge in heavy cloud. It was at this point that the pain involved in being carried really began to make itself felt. Think about it. This is exactly what they did to people when they tortured them on the rack. Limbs and joints stretched beyond normal limits hour after hour, my ribs crushed against the carrier’s back. It was excruciating. But what could I do? Leave me here? Walk? Or suck it up? I sucked it up.

Everything faded to a pain induced blur as we traversed endlessly over the high ridge. The carrying crew changed regularly every 10 or so minutes and I began to look forward to this more than I’ve ever looked forward to anything in my life. Occasionally we would have an extended break but it was never long enough. After a while I even developed carrying preferences. I fitted nicely into the contours of Jitman’s or Nigma’s backs but was a bit too small for Lama’s. How selfish I thought. Here I am thinking this way while these guys are giving everything they’ve got for me. This is all my doing, not theirs. Berating myself, I slipped back into semi consciousness as the awful journey went on.

After what seemed like hours – and, in fact, was as long as it seemed – it became obvious to even my addled brain that we were descending steeply. This brought new pain both to my tortured back and to the porters’ knees and legs, particularly Lama’s, as they sometimes literally fought for secure footing. Compensation was at hand, however, as the first trees and then the sight of the first villages, far, far below came into sight.

We came down over 700 vertical metres from the high ridge and suddenly came across something man-made. A wooden frame and evidence of cultivation. Spirits soared. Another hour and there below us was the camp Krishna had found the previous day. Down again. Soon be there. But not soon enough. I’d had enough and begged the guys to put me down. They were reluctant but let me hobble a bit, supporting me on both sides. By this means, I hopped into camp 20 minutes or so later to find Birkha waiting with a chair and a cup of tea and Krishna and Phanden having just finished putting up my tent. Once again I couldn’t trust myself to speak and just grasped hands all round in silent gratitude. It was 4pm.

Krishna had chosen well. Our camp was on a spacious summer pasture with good water. After over a week above 4,000 metres, we were now at 3,300 and surrounded by big, ancient trees. It felt wonderful.

An hour later and it got even better. Into camp walked Chandra’s two porters with food, the obvious deduction that the route ahead “went” and, of course, news.

Chandra had reached Bhulbhule and successfully contacted Ang Rita from there. Ang Rita was in Siklis and a helicopter was standing by in Pokhara. Ang Rita had even sent three porters up over our route from Siklis with food. The villagers in Bhulbhule knew all about the body on the Namun and, in fact, there were rumours that there were

three bodies up there. This didn’t bear thinking about but at the very least, rescue would appear to be at hand. The helicopter boys as well as Phanden, Taschi and Krishna had worked miracles today but I'm sure there was a profound look of relief on all six faces when we received this news.

Rescue

![Final Camp]() Rescue camp

Rescue camp![Rescue!!]() Rescue at hand

Rescue at hand

Morning revealed just how idyllic our camp was. A short walk/hop to the edge of the ridge and the mountainside dropped off precipitously to the valley 2,000 metres below. Looking north we could make out our route of the previous day. We had contoured the west side of Sundar. In fact with a summit altitude of 4,330 metres we must have been almost on top!

Morning also brought a helicopter!! Although we knew that it MUST come today, I think we were all quite surprised when it actually roared over the edge of the ridge. After one exploratory pass to pick out a landing site, the pilot set the machine down gently and out jumped a smiling Chandra to a hero’s welcome. Everyone rushed around to get my gear together – but wait – the pilot’s switched off. He wants a cup of coffee! And with that I knew I was as good as back in civilisation.

Hari and I were eventually loaded on board and at 8.45 we took off. Ten minutes later we were in Bhulbhule and there was Ang Rita. If I thought the emotional aspect of the experience was over, I couldn’t have been more wrong. The whole village had turned out. I didn’t flatter myself to think that this was on my behalf. More about the novelty of the helicopter I would have thought. But no; here came everyone with garlands of marigolds for Hari and me, given in gratitude for our deliverance from the mountains. It was silent grasping of hands time again as I struggled to keep my emotions in check.

![Porters and The Helicopter]() Everybody happy

Everybody happy | ![Approaching Bhulbhule]() Approaching Bhulbhule

Approaching Bhulbhule | ![Reception in Bhulbhule]() Reception in Bhulbhule

Reception in Bhulbhule | ![Bhulbhule]() Is that for me?

Is that for me? |

After refueling we took off again at 9 am and landed in Kathmandu at 9.30. By 10 am we were being seen by a doctor in the Canadian clinic there and by 10.30 were all through. Hari had been diagnosed with impetigo, liberally dosed with antibiotics and his sores cleaned and dressed (all paid for by Mark). A week later and they were almost completely healed. I was fitted with a (useless) knee brace. By 6.30 that evening I’d had an MRI done and was diagnosed. Surprise, surprise; they said I had torn my medial meniscus.

Aftermath

Four days later I flew back to Pokhara to re-join the group. It was obvious even before the helicopter finally arrived that all this was adrenaline enough for one trip. Everyone had already resolved to head out to Besisahar once Hari and I had been evacuated.

They had managed to descend all the way from our last camp to the Annapurna circuit in a single day and walked out in 2 days from there. The universal opinion was that it would have taken 2 or 3 days to carry me down what turned out to be a steep and dangerous route IF an accident hadn’t happened on the way. Ultimately, the appearance of a helicopter had been in the nick of time.

The porters who had been sent up from Siklis had been contacted and had already returned safely.

The next day Taylor and Mark left early. Taylor home to her new son in London and Mark to visit Hari and his family in their village. The rest of us enjoyed the delicious boredom of Pokhara before the long journey home. By this time I could hobble tolerably well but needed as much time as possible before the prospect of 24 hours on an aeroplane.

It’s now just over a month since this incredible experience. I’ve already had successful surgery - many thanks to Dr Mike Gilbart and his staff at the Cambie St Clinic in Vancouver - and am well on the way to a return to the hills next spring, if not before.

![The Helicopter Boys]() The Helicopter Boys

The Helicopter Boys | ![Helicopter Party]() Helicopter Party

Helicopter Party |

All in all, I think I got off pretty lightly.

Epilogue

The enforced idleness of recovery has given me tons of time for considered reflection. How do I feel about it now? At first I was angry. I’d trained hard for this all summer. My gear was the best. I was fit, warm and comfortable. I never got sick nor had any serious altitude problems other than the occasional mild headache. My bloody body just let me down and I was pissed at this clear indication of my mortality.

Later, I took a less jaundiced view. I had been privileged to experience something that we’ve long ago lost in the west. Genuine selflessness, real concern for another human being in distress, willingness to help no matter what the consequences and without thought of reward or what it cost in personal effort. We have much to learn from “primitive” societies such as Nepal – or should I say re-learn. I for one intend to try.

What of the body on the Namun Bhanjyang? At the time of writing we’re no nearer to finding out the truth. In spite of the rumours in Bhulbhule, we’re all convinced there really was only one up there. Of more than this we can’t be sure. Various stories are circulating. One has a party of seventeen hiring porters in Siklis and failing to cross the pass. Another has a group of seven approaching from the north and crossing the Namun before getting into trouble. Personally I don’t buy this. Only the most heartless of westerners would build a snowman

after losing a porter to hypothermia. Most likely whoever was involved approached and retreated the same way we did. Otherwise – and assuming they were caught in the same storm we were in Ghalageon - we would have met them coming down. We’re still searching and will continue to search for answers. Anyone who reads this and knows anything is urged to contact me.

Route Map

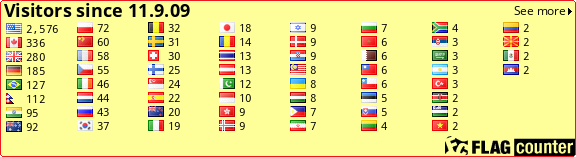

The southeast sector of the Annapurna Wilderness showing the area north of a line roughly between Pokhara and Besi Sahar. Visitor Statistics

Just for my interest - but feel free to have a look.

Comments

Post a Comment