Preface

This essay is a continuation of my Theory of Alpinism, a work in progress. Much of the theory is focused on the individual - how and why we, as individuals, climb; what this essay will attempt to understand is why so often this profoundly individual exercise is partaken of collectively. There is a certain practical significance to this, even a non-climber could intuit that two linked by a rope is safer than one, but philosophically the issue is much deeper. In order to examine the ethical justifications and implications for roped climbing we must first examine the place of the individual in our cultural tradition.

Introduction to Individualism in Western Thought

[This section is liable to be a bit dense to those who have not studied philosophy, please bear with me, I promise will relate it back to roped climbing eventually]

The natural conclusion of the epistemological developments of modern philosophy was the supremacy of the individual. The problem of knowledge is roughly articulated as follows – there are two potential ways to have objective knowledge: empirical and rational, the world is either intuited by our minds or imprinted upon us by sensory experience. Neither is effective in a rigorous sense. In the case of the former, rationalism, we have no basis for any knowledge, no matter how purely rational (like our knowledge of being and essence), without sensory experience; in the case of the latter, empiricism, we do not know to what degree our sensory experience is shaped by our pre-established conceptions. Both objections can be reduced to the same dilemma, our brains make sense of the data our senses gather in a certain way, constructing the world we perceive and the chances of this subjective world correlating perfectly, or even closely, with the objective world, the world as it actually is, seems small.

What we are left with is what the Ancient Greeks called Skepticism, which followed from Socrates’ claim that because he did not know everything, everything he thought he knew could potentially be proven wrong by what he did not know, and therefore he knew nothing with any degree of certainty. While this is all true and reasonable on a certain level, very few accept this level of skepticism in practice; even if we cannot know the objective world, we act as though we can and in most cases our assertions are born up by their consequences. Therefore it is clear that although it seems like we cannot know anything, we must know many things.

Progress against this skepticism can be made in a variety of ways. In the 17th century, Rene Descartes made the famous claim that because, no matter how delusional we may be, we are undoubtedly thinking, we must exist because something must exist to be doing the thinking. This effectively side-steps the problem of empirical knowledge by showing that under no circumstances can the existence of our thought be doubted, it is a necessary precondition of all sensory experience.

![Philosophers]()

Immanuel Kant approached the problem from a different perspective in the 18th century, his argument was that reality could not be known objectively because all that we perceive are representations of things, and not things in themselves, yet he maintained that this subjectivity did not imply total relativity (the dreaded skepticism). Our subjective experience, according to Kant, is not without a certain order. For us to have any experiences at all, both time and space, and therefore causation, must exist. In this way a solid foundation of subjective knowledge may be built, but it is the nature of subjective knowledge for it to be individual – even Descartes’ “I think therefore I am” cannot intuit the existence of another thinking thing. This means that although our subjective experiences seems to be ordered in a certain non-arbitrary manner, we have little reason to believe that anyone else’s is ordered in the same manner, or even that anyone else exists in the same manner that we do. From a literal interpretation of this comes the most radically individualistic strains of modern thought: I am only responsible for and to myself. If taken absolutely, this the philosophical basis of anarchism – humans are better off without commitment to others.

When the common thought was that God was all we could know absolutely (examples of this belief can be found in the writing of the apostle Paul, Augustine of Hippo, and Thomas Aquinas) men naturally organized themselves into ecclesiastical structures – the fundamental relationship from which all others derived was that between man and God. But in the modern period the only absolute knowledge became that of the self, resulting in the understanding of ourselves as individuals. Yet we attach ourselves to others, by social bonds, by systems of allegiance, by ropes. We always have and by all evidence always will. Despite, or perhaps because of, our existential loneliness, we are social creatures. A monotheist in the Judaic tradition would say we were not meant to live alone – God made not one man, but two: Adam and Eve. A Darwinian Evolutionist would say that man, like many animals and particularly like higher-order many primates, developed social groups for the betterment of the individual. Those individuals which formed tribes, and later cultures, were more successful: ate better, bore more offspring, lived longer and healthier lives. Humans have been doing this for so long that it might seem to be the only way to live, but man is an able hunter and many higher-order predators live alone for much of their lives – felines, many bears, birds of prey, nearly all living reptiles – coming together only to mate. Although many humans feel an acute sense of loneliness when separated from their social environment, men are nothing if not adaptable and, if unusual, hermitage is not unknown in many cultures.

Philosophy and Roped Climbing

Any time humans come together to work in groups they do so for a perceived benefit, yet it also clear that there are many detrimental effects of sociability. Both John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, writing in the 17th and 18th centuries, admitted that humans living in their natural state need far less social structure than exists today. While Locke saw the transition from anarchy to government as a triumph and Rousseau saw it as a tragedy, they both maintained that what humans did in this regard involved a set of sacrifices for a perceived end. When we form groups – families, governments, rope teams – we sacrifice, in varying degrees, our individuality. All that we truly know, and thus all that we can truly control, is the individual; and so this sacrifice is no small thing. When we sign a contract or tie in to a rope team we are sacrificing our control over our only real and natural possession: ourselves. This is all to emphasize the severity of these decisions – joining ourselves with other men is not a matter of course and we should not treat it as such.

Here is where I will try to cease speaking of humanity as a whole and focus on the subject at hand: roped climbing. When mountaineers use a rope they do so for the expressed purpose of safety, the theory being that in some conditions the consequences of a minor mistake or the risk of objective hazards are so great that to proceed under one’s own strength would be foolishness. Put differently, there is terrain on which the risk of a fall in relation to the consequence of a fall is so great that ascent is infeasible. Under these circumstances climbers often choose to use a rope. In order to speak to the ethics of roped climbing it is necessary to understand how the tradition has developed and what form it currently takes.

Brief History of Roped Climbing

The use of the rope has evolved considerably from its genesis in 19th century Alpine scrambling. The original roped climbers were British vacationers and their ropes were often little more than clotheslines affording nothing but psychological protection, as evidenced by the infamous first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865, during which four of Edward Whymper’s companions fell to the their deaths when one of them slipped on a steep slope. All six men would likely have been killed had one of the connecting ropes not snapped. Advances in technology, the carabiner, piton and standardized hemp, and later nylon, ropes, came to afford somewhat more solid protection.

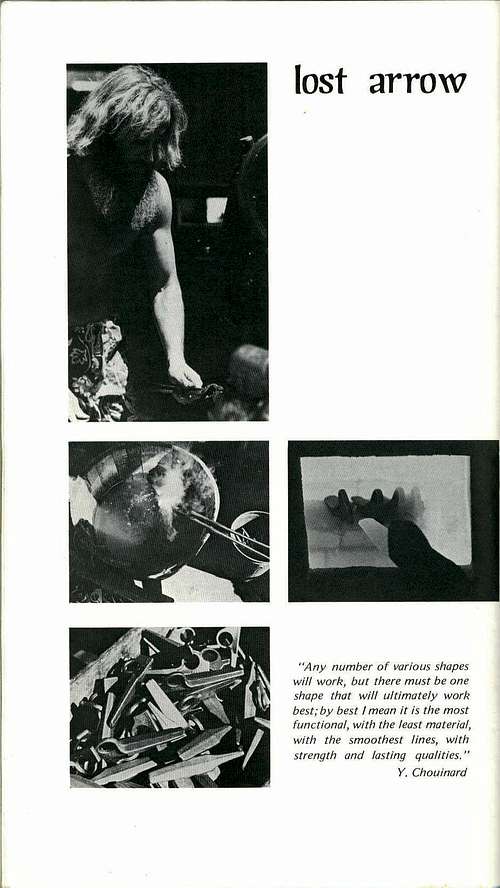

The basic method was, and still us, as follows: in a team of two climbers, each man attaches himself to an end of the rope. As the leading climber ascends the rock or ice face he attaches points of protection which he then clips into the rope between him and the following climber with a carabiner. These originally consisted, in the British tradition, of slings over rock protrusions but have since evolved into pitons, ice screws, pickets, and a whole, ever changing, variety of chocks, nuts, hexes and caming devices.

![Pitons]()

What has just been described is, in essence, the running belay – both climbers moving simultaneously, with the second climber removing the protection, or at least unclipping the rope, as he ascends. This is used mostly for terrain in which the consequences of a fall are very great, but the risk comparatively small. If the risk is higher, which generally amounts to a steeper incline, a multi-pitch belay system may be used. As can be easily imagined, either of these types of climbing are much safer, but often much slower, than what is now termed free soloing. Their use is nearing the point of dogma in the climbing community, with free soloing being reserved for the masterstrokes of the elite. Roped soloing also exists and involves self-belay systems; which, contrary to expectation, are actually more complex and time consuming that dual-climber belay systems; because of this, and other safety-related factors, roped soloing is becoming exceedingly rare.

There are a variety of other practical reasons why climbers, roped or unroped, climb in teams, companionship being foremost among them. In the case of injury it is commonly accepted that climbing in groups is safer, particularly in groups of three or more, and particularly over avalanche terrain. This is, however, a point of some contention. The appropriate size for a climbing team has oscillated between a dozen or more and a pair, the standard trade-off being safety versus speed, but there are two rather infamous cases that challenge the conventional logic.

During the third American K2 expedition of 1953, the incapacitation of one team member (of six) endangered the entire group to the point where his death during their descent quite possibly saved the lives of the other five team members. This can be compared with the Simpson and Yates Siula Grande incident, in which one member of a two-man team was injured, leading to a disastrous rescue scenario that ended when the uninjured climber cut the rope attaching himself to the injured climber and then finished the descent alone, assuming his partner was dead. The injured partner then crawled after him, arriving some three days later. While neither case can be regarded as remotely typical, or even all that comparable, they serve to show that teams, of any size, do not insure safety. Never-the-less, it is almost universally recognized that climbing in a team is safer than climbing solo. Alpine and particularly high altitude soloists have a notoriously high death rate, even from such mundane accidents as falling into a crevasse. However, there are dissenters.

Alison Hargreaves was an extremely controversial British female soloist, controversial especially since when climbing she left her husband and three children at home (it should be noted that this was considered controversial mostly in the mainstream press, and not in the climbing community). Before her death on K2, she was quoted as saying that she climbed solo because she felt it was safer – the idea was that once one reaches a certain level of competence, teammates merely multiply the objective hazards of a route. An example of this would be that the chances of a team of two being hit by rockfall is over twice that of a solo climber.

Despite the many examples of great climbers who have made a career out of solo climbing – Walter Bonatti, Reinhold Messner and Alex Honnold being a few, soloing is still regarded by most as an unjustifiable, and indeed – unethical, risk. This disconnect, the simultaneous glorification and condemnation of the act comes from a misunderstanding of the nature of risk. When one reads about the great feats of Bonatti or Messner or watches videos of Honnold free soloing, one does not get the impression of normal human activity; there is a strong tendency to see these men as demigods, not quite divine, not quite immortal, but, like Achilles, set apart from the rest of humanity. This is how the disconnect is created – “Well of course Bonatti could do that, he was Bonatti, normal laws of probability did not apply to him.” Obviously this is false, but the problem is more what it conceals than what it misconstrues. Bonatti, Messner, and Honnold were and are superb climbers, climbers whose skill level was and is so high that subjective hazards barely exist for them. Watching a video of Honnold soloing half-dome I caught myself wondering, so what happens if he slips, what happens if he grabs one hold just a little bit off? This would be the same as asking me that question as I solo four-class terrain, and the answer would be basically the same, “Do you know what I’ve climbed on a rope without falling?” In essence, the majority of the danger of a climb is related directly to personal skill level, what is dangerous for one climber to top-rope might not be dangerous for another to solo. There is no truly objective hazard.

The Epistemological Dilemma in Roped Climbing

The practical issues of roped climbing and the philosophical dilemma of knowledge may seem unconnected, but the ethical and epistemological implications of the decision to join a rope team are anything but trivial. As a climber, one can only know oneself, one’s own skills and limits, and never another’s. When one joins a rope team one has linked oneself to an unknown, one has given up control of one’s own trajectory. This applies just as much to issues of route-finding and turn-around times as to accidents. In order for a rope team to function it has to be a binding agreement, if under any circumstances one would unrope to save oneself, one never should have been roped in the first place. This is the level of trust members of a rope team must have for each other – that the only way they would separate is by mutual consent. Without this, the rope is meaningless and affords no protectional at all, psychological or physical.

Although there has never been, to my knowledge, a philosophically rigorous system of climbing ethics, there is an unspoken code, and from this much of the logic in this essay is derived. A potential basis for this code is a form of consequentialist ethics I will here outline. Ethics is often seen as a way of determining moral right and wrong – this is illusory. As the moral absolutes implied by the abstracted terms ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are inherently fallacious (rightness and wrongness are not real attributes of actions), what ethics actually articulates is always ends-based. Given an end, an action can be judged as right or wrong, one might better say correct or incorrect, relative to the achievement of that end. This begs the question, what is the end of climbing? It is my belief, although I have yet to argue this rigorously, that the end or the purpose of all justifiable climbing is self-reliant, exploratory mountaineering, for which the purpose is to experience the wilderness. Yet what is here being discussed is not the ethics of climbing as a whole, but the ethics of roped climbing, for which there is a much narrower end – the bodily preservation of each member of the team. Therefore any action which compromises the safety of the other member(s) of the rope-team for the benefit of oneself must be considered unethical. This can be judged by an Alpinist version of Kant’s Categorical Imperative: in order for the action of a rope-team member to be ethical, it must be universally applicable. This basically reduces to a trust game, one must be able to trust one’s rope-team member(s) not to come up with obscure exceptions to normal practice, which, if one obeys Kant’s categorical imperative, will not occur.

Eventually, like with all social bonds, the justification for roped climbing comes down a cost-benefit ratio for which there can be no absolute rule. There is a clear ethical standard for how rope teams should operate but none for how rope teams are formed, as it is entirely dependent on the climbers involved. A strong emotional attachment between climbers is possibly the best way to avoid a breakdown of the rope team relationship (the point at which one climber becomes an unwelcome burden on the other.) Aside from familial teams this is somewhat rare, and so what may substitute is a rough parity of skill level: one should not join a rope team with a substantially weaker or stronger climber. Unfortunately, climbers do exactly that on a regular basis. Some eras and regions are known for a strong amateur climbing fraternity, Post-WWII Europe for example. Others eras are not, notably much the 19th century and, on some levels, the present day. While, in the 19th century, most ascents were made by vacationing Englishmen with local guides, modern day guiding owes almost nothing to that tradition. The 21st century guided climber most often joins a guided mini-expedition instead of recruiting locals for a personal project. The ethical problems of guided climbing are beyond the scope of this essay, but it can be safely admitted that the guide-client relationship is (acceptably or not) an exception to the rule of rope-team parity.

Touching The Void and the Limits of Rope Team Ethics

The metaphorical litmus test of any ethical system is its ability to account for controversial circumstances in a satisfying manner. Indeed, there would be no need for logically sound ethical theories if such controversies did not exist. The archetypal rope team controversy may be the aforementioned Simpson and Yates 1985 Siula Grande incident. As Simpson’s book on the matter, Touching the Void, is among the most widely read mountaineering books of all time, I will assume a familiarity with the basic events.

![Touching the Void film poster]()

Upon returning to England, Yates faced intense criticism for his actions and is often referred to as “the man that cut the rope.” In the eyes of many, the cutting of the rope was an unpardonable sin. If Yates had known that Simpson was dead or doomed to die his actions would have been justified but as he did not know this, he violated the ethics of roped climbing. In a certain formal sense this is true, what Yates did, regardless of how it turned out, appears to violate the categorical imperative; i.e. nine times out of ten, cutting the rope would be tantamount to killing one’s partner. Strangely enough, both Simpson and Yates maintain that they did the right and ethical thing.

The irony is that Yates’ actions saved Simpson’s life in two ways. Once Simpson was injured Yates was under no obligation to help him down the mountain, single man rescues like what they attempted are almost unheard of; yet he did not abandon Simpson with a promise to return with help (which would have taken weeks and amounted to the recovery of Simpson’s body for burial) but chose to continue, knowing that he was linking himself to a pragmatically much weaker man. The second manner in which Yates saved Simpson’s life has to do with the nature of exposure. Once Simpson realized that their rope was not long enough to reach the bottom of the cliff he knew his only choice was to climb back up the rope. If he had been able to Prusik up the rope he could have gotten his weight off of Yates’ belay device, allowing him to descend to Simpson’s position. But in the process of tying the knots, Simpson dropped one of the slings, making ascent up the rope impossible. Hanging there as he was, in midair at night in a blizzard, he would have died of exposure in a matter of hours, but once Yates cut the rope he was dropped into the shelter of the crevasse and once he climbed out it was morning and the weather had cleared.

Yates had no way of knowing Simpson had dropped his Prusik sling and was hanging helplessly in midair and the ethics of roped climbing thus far articulated would mandate that he remain where he was until Simpson re-established contact, but if he had done this Simpson would have died. Only Yates’ violation of the apparent ethical code saved Simpson’s life. Either this incident is a bizarre exception to the rule or there is a deeper complexity. In some ways the issue relates back to the problem of knowledge, one only ever has knowledge of oneself but when on a rope team one is literally tied to something one does not have knowledge of. This is an issue even in relatively mild sport climbing – belay devices can be judged on how well they give a “feel” of the lead climber’s movements; the more the belayer can feel the lead climber the more effectively he can belay. It is as if rope-teams operate as a single organism and the more they are of one mind the more effective they can be. Cut off by night and weather the way Simpson and Yates were, the issue of communication becomes severe. It is a fact of climbing that one will not always have good communication with one’s team members, but how this relates to the ethics of roped travel is difficult. Given restricted knowledge of a teammate’s situation, what duties can a climber have? If not for such dramatic examples as the that of Simpson and Yates, one could simply accept that this is one of the hazards of roped climbing.

The question is thus, what are the ethical duties of a climber who has lost contact with his partner? The options would be, no duty – sever the connection, unrope by any means possible, total duty – maintain the connection as if one still has communication, or some duty – somewhere between these two extremes. Clearly the first two options are infeasible, a climber should no more abandon his partner at the first loss of communication than he should wait immobile as if the situation were normal. Under many circumstances the climber could attempt to reestablish communication, had Yates possessed a snow anchor (theirs had been left as rappel points) the entire incident could have been averted, but this is not always possible. It could be claimed that the climber’s duty to his partner has some sort of time limit, perhaps one could judge the time required before they could be assumed to have died of natural causes and then proceed alone. There are two problems with this proposition, the first is that one can easily imagine a scenario in which that amount time would be the same for both climbers, the second is that under that rule Simpson would have died.

The critical factor, which has been neglected until now, may be that Yates was not himself well anchored. He had been lowering Simpson from a series of seats dug into the snow, essentially turning his body into a dead-man anchor, and his seat was disintegrating. Had he not cut the rope, he too would have gone over the cliff, his greater momentum likely resulting in dire injury. If Yates’s action is considered like this, that Simpson lived becomes a random exception and the question becomes whether climbing partners are obligated to sacrifice their lives for their strict ethical duty to their partner. This can in turn be broadened to whether climbers are required to risk their lives in rescue attempts, a matter already under intense scrutiny due to recent events on Mount Everest, which is entirely beyond the scope of this essay as it does not relate strictly to rope teams.1 Returning to the formal ethics, what Yates did can then be seen to be ethical as long as climbers are not obligated to sacrifice their lives for their team member, (which is the default assumption until an argument has been made otherwise); what he did can be easily generalized into a universal rule: if a partner’s fall will result in fatal fall for all rope-team members, (which, in a protracted way, is what Simpson and Yates were experiencing) a rope should not be used, as it only multiplies the effects of subjective and objective hazards rather than minimizing them.

The problems here raised clearly exceed the Siula Grande incident; even if issues of die-or-let-die are regarded as another topic, the straightforward problem of what to do when communication has been severed remains unresolved. The only possible escape seems to be some sort of frighteningly vague ‘judge according to individual circumstances’ relativism. Given how we like to think of ethics, as a way of avoiding difficult decisions using prearranged principles, this answer is highly unsatisfactory, but we must recall the individual nature of climbing. Rope-teams are an exception to standard wilderness practice, they are a way of dealing with a certain ratio of risk to consequences, and are not a perfect answer to all climbing dilemmas.

1 An interesting fact to note is that on the South Col route of Everest, the standard route climbed by hundreds each year, rope teams are no longer used, instead teams of sherpas set fixed ropes along nearly the entire route.

Bibliography

Plato’s Five Dialogues

Mediations - Rene Descartes

Critique of Pure Reason - Immanuel Kant

Two Treatises on Government - John Locke

Origins of Inequality - Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Killing Dragons - Fergus Fleming

Scrambles Amongst The Alps - Edward Whymper

K2: Life and Death On the World’s Deadliest Mountain - Ed Viesturs

Touching The Void - Joe Simpson

This Game of Ghosts - Joe Simpson

Into Thin Air - Jon Krakauer

Dark Shadows Falling - Joe Simpson

There is a small part of me, the part of me that is a 3rd year history major at Seattle University, that dies inside every time I don't cite my sources in proper Turabian style. The average wikipedia article is more scholarly than the pieces I've been putting on Summitpost.

Part of it is just laziness, I really don't want to re-read the Critique of Pure Reason looking for where Kant most succinctly says what I am likely misquoting him as saying. But mostly it has to do with what we learn in writing classes as knowing your audience and knowing your medium. Summitpost does not have a mechanism for footnotes and I seriously doubt the average summitposter is interested in a serious discussion about the implications for radical individualism in Descartes and Kant. Anyways, all apologies to anyone shaking their fist at my appallingly lax academic standards, if it's really bothering you that you don't know what translation of Rousseau I used, you probably should not be on this website.

Comments

Post a Comment