mvs - Sep 13, 2010 2:47 am - Hasn't voted

Re: Surprising!I think that is a really interesting paradox too. The experienced have become skilled at seeking out and staying on dangerous terrain for a greater percentage of the total trip time.

xpda - Sep 14, 2010 1:38 am - Hasn't voted

Re: Surprising!The experienced people spend a lot more time per year climbing, on average, so the accident rate per hour should be quite a bit less than inexperienced people, despite the fact that the experienced ones are doing harder stuff.

LadyWawa - Feb 9, 2011 11:59 pm - Voted 10/10

Re: Surprising!This surprised me the most too! Fascinating article!

fossana - Sep 13, 2010 12:39 pm - Hasn't voted

good stuffThanks for putting this together. The other useful bit of data would be to normalize the data by # of participants. For example, are there more accidents in CO b/c there are factors that contribute to more accidents or are there just more people climbing? If you have age & experience data by stratified by state you could also do a multivariate analysis to weed out exactly which factors are contributing to morbidity & mortality per geo. I can help you set this up if you PM me.

StephAbegg - Sep 14, 2010 12:44 am - Hasn't voted

Re: good stuffI agree this would be fascinating. Ideally, I'd like to do a giant multivariable regression on this data. But the data is not specific or complete enough to do that, I don't think. The only state-by-state data provided is the total number of accidents (since 1951) and total number of fatalities (since 1951). It would be interesting to at least have some numbers on how big the climbing "population" is in each state, but I have not been able to find this data.....

fossana - Sep 30, 2010 7:47 pm - Hasn't voted

Re: good stuffIf I come across anything will let you know.

foweyman - Sep 14, 2010 7:45 am - Hasn't voted

unsupported conclusionsI appreciate your efforts to update your post based on peoples comments, but it still contains many non-factual, illogical, and misleading statements such as: "the statistics indicate that it's more likely you will get in an accident driving to or from the climb than on the climb itself. Hence, in this sense, climbing can be viewed as safer than driving!"

The presented statistics do not support this at all because there is no data presented on the amount of time spent driving to and from a climb and no data on time spent climbing. The only conclusion that can be made from the presented data is that more people die in car accidents than climbing accidents.

Similarly, the "comments" on the table about the relative safety of climbing and driving are misleading because they don't take into account that people spend far more time driving than climbing. By your logic jumping off the Empire State Building without a parachute is safer than driving because many more people die in driving accidents. Just because more people die from doing activity A than B does not mean that a person doing A is more likely to die than a person doing B.

I won't speculate on your motivation for drawing biased and misleading conclusions in order to understate the dangers of climbing, but the post would be more credible and meaningful if an objective approach were used and the limitations of the data were clearly stated.

vanman798 - Sep 14, 2010 12:46 pm - Hasn't voted

Another point of view...The author Maria Coffey states this in her book "Where the Mountain Casts Its Shadow: The Dark Side of Extreme Adventure"

"According to 2001 figures, in the United States approximately 41,000 people are killed every year in motor vechicle accidents, and 3 million more are injured. Out of a population of 272 million, that's approximately one death in 7,000. When I asked Steph Davies, who is thirty, how many of her friends have died in climbing accidents, she added eight. The American alpinist Mark Twight, who is in his early forties, says that forty-three people he knew have died climbing. Joe Simpson has lost, on average, a friend a year to the sport over the past fifteen years. How man people of their age have lost that many friends in automobile wrecks?"

Snidely Whiplash - Sep 14, 2010 6:23 pm - Voted 10/10

Fascinating subjectI love these kind of maps. What strikes me is how huge the fatality statistics are for the state of Washington, which outstrips every other state including California, which has a population about 5 times greater. As Bob Sihler already pointed out, beyond Rainier, Washington is not really a major destination for trophy climbing. Does this point to more hazardous snowpack conditions in Washington, or more dangerous weather?

CClaude - Sep 16, 2010 10:56 am - Hasn't voted

alsoAlso years experience is a poor qualifier for experience. There are some people who have climbed 20 yrs but only a couple of times a year (or maybe once a week), but others who have climbed 2 years but 250days/year.

Also there are areas that chronically under report accidents, the Gunks in New York coming to mind.

StephAbegg - Sep 19, 2010 3:37 pm - Hasn't voted

Re: alsoI continue to welcome everyone's comments and am very happy to see that this article has generated a very intellectual and fascinating topic of discussion on summitpost. However, with school starting up for me I won't be able to keep the article up to date with comments, but please use this comments section to voice your interpretations an suggestions on improvement. Thanks1

nickmech - Sep 19, 2010 8:46 pm - Hasn't voted

pie charts?I must be in the minority here but pie charts are for nerds. I do find reading the AAC yearly report of great interest.

drjohnso1182 - Sep 20, 2010 11:21 pm - Hasn't voted

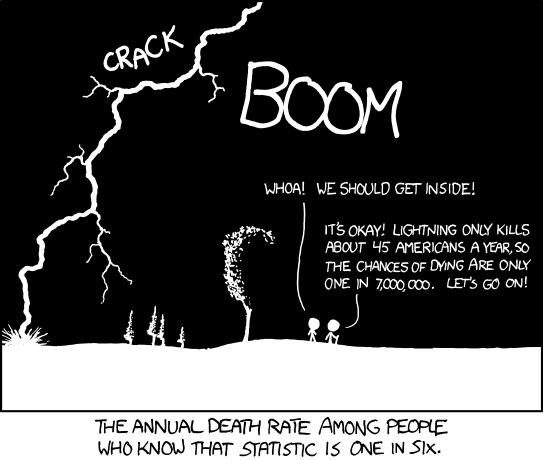

Conditional RiskToday's xkcd comic is unusually appropriate:

http://xkcd.com/795/

StephAbegg - Sep 21, 2010 12:25 am - Hasn't voted

Re: Conditional RiskLove it! Sort of sums up the whole conditional risk issue we've been tossing around!

EastKing - Sep 21, 2010 1:34 am - Voted 10/10

Awesome article.Unfortunately I had read this after my injury. :)

Diggler - Sep 28, 2010 1:25 pm - Voted 10/10

Interesting compilationWhenever I get my annual issue of ANAM, I usually read it pretty continually until I'm finished- not only have I learned a great deal throughout the years using this resource (or so I like to think), it is fascinating (if morbid) reading material. It is a good idea to ponder the various primary & contributing reasons.

I think that it would be interesting to compare the per capita rates of accidents/fatalities on a state-by-state basis too- this could be enlightening (California, for example, has far more people than Washington & Colorado combined).

I think that it would also be worth noting the differences in accident locations. For instance,

- Denali vs. other climbing locations in Alaska- I would guess that the overwhelming majority of accidents in Alaska occur by visiting climbers, & even more specifically, on Denali itself. If one were to look at accidents outside of Denali, I'd surmise that there would be very few compared to other places.

- same thing on Hood, Rainier, etc. (big glaciated Cascade volcanoes)

- analyzing statistics by locations primarily frequented by visiting climbers (Denali, Rainier, Hood, etc.) vs. locations primarily climbed by 'locals.'

"Below is a bar graph (sent to me by my friend Clint Cummins) showing the main causes of death in the US in 1988 for age 15-44, by sex." I had no idea that anyone kept track of this data! I always thought that this would be the preferred way to go myself.

Thanks for putting this up- a good contribution.

Vinny - Sep 29, 2010 5:08 pm - Hasn't voted

NORTH American AccidentsNice work Steph!

my only criticism is you neglect the big part of north America including your beloved Valhallas.

It's an ongoing pet peeve for Canucks like me. You are not the first nor will you be the last. ; )

http://www.americanalpineclub.org/pt/accidentsinnorthamericanmountaineering

It would also be interesting to break down types of climbing into Sport/Trad crag/Alpine/altitude/glacier etc. The questions only become more complex.

I recall a statistical comparison between high altitude climbing and paragliding w.r.t. risk of fatality.

But yes, the majority of mountain rescues are hikers.

Heal well! Keep up the great exploits and journaling.

Kevin

EMRU/Providence

StephAbegg - Sep 29, 2010 9:40 pm - Hasn't voted

Re: NORTH American AccidentsMain reason I did not include Canadian data in the location data is that I do not have a North American (US + CND) Shape file for making my cartograms..... =)

Ze - Oct 6, 2010 9:49 am - Hasn't voted

excellent pagewhat software do you use to make the cartograms?

StephAbegg - Oct 6, 2010 10:48 pm - Hasn't voted

Re: excellent pageI used some java software made by Frank Hardisty, based on Gastner and Newman's algorithm:

http://people.cas.sc.edu/hardistf/cartograms/home.htm

Comments

Post a Comment