|

|

Article |

|---|---|

|

|

Mountaineering, Trad Climbing, Big Wall |

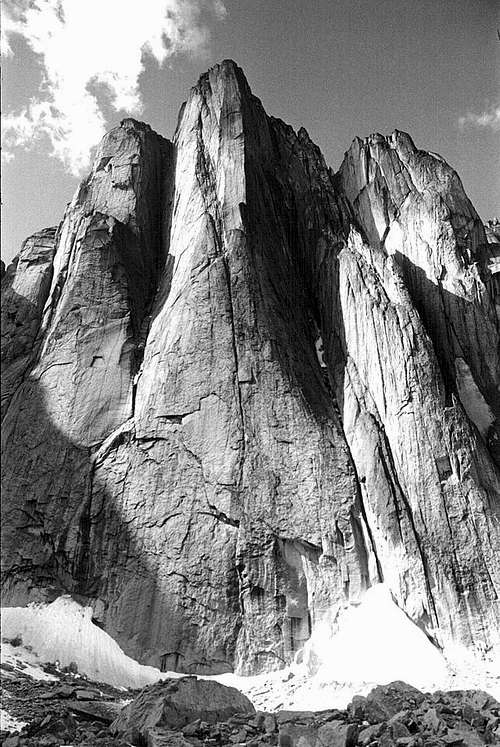

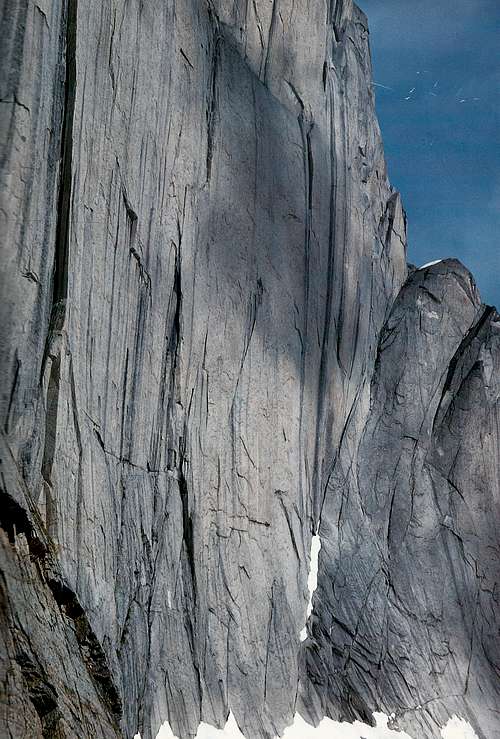

The panoramic photo above depicts McCarthy's favorite mountain hangout: The Cirque of the Unclimbables. In the middle foreground is Snowpatch Spire, in the distant left one can see the large face of the Grade VI big wall Mt. Proboscis, and in the upper right with the light on it the striking face of the Lotus Flower Tower.

New Yorker in the Mountains – Life and Climbs of Jim McCarthy

-James (‘Jim’) P. McCarthy (1933) (climber)

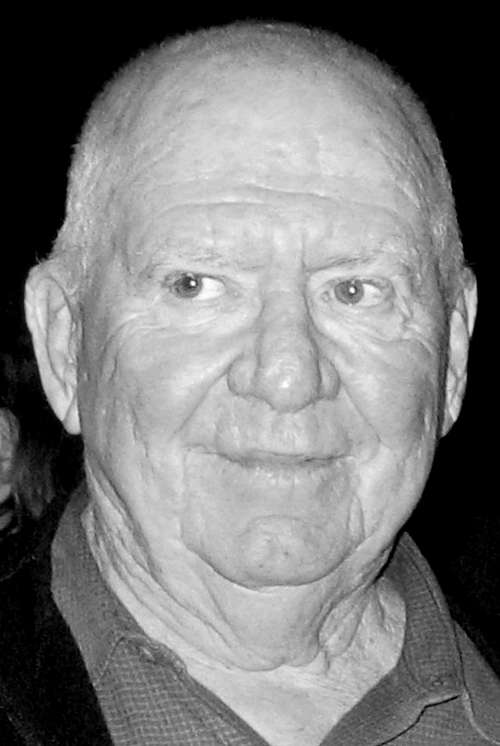

Jim McCarthy in 2008. Photo: Joe Bridges

Contents

Formative Climbing Years at the Shawangunks (‘Gunks’)

First Forays in the Big Peaks of the American and Canadian West

Stirring the Pot in New York with the Self-styled ‘Vulgarian Gang’

Breaking Open the Standards Framework during the 1960s

A Senior Ambassador of North American Climbing

First Ascents (FA) and First Free Ascents (FFA)

Anecdotes and Remarks about Jim McCarthy.

Introduction

James (‘Jim’) McCarthy is one of the premier US rock climbers and mountaineers of the second half of the twentieth century. He is perhaps most famous for his bold and difficult first ascents of rock climbs in the east coast climbing Mecca of the Shawangunks – a range of steep, blocky and overhanging metamorphic sandstone cliffs known colloquially as the ‘Gunks’ along the Hudson River valley near New Paltz, New York. Developing a reputation as the best climber there through the 1950s and 1960s, he later made friends with key climbers from the western US coast and mountains – such as Tom Frost, Yvon Chouinard, Royal Robbins, Layton Kor and Fred Beckey. With them and others, he developed serious extended length and ‘big wall’ alpine-style techniques and put up first ascents in this fashion throughout North America.

McCarthy was known for an uncommon mix of intense competitiveness and genial friendliness. This attitude was crucial in opening the North-Eastern climbing scene of the fifties and sixties, where he had become a de facto but ever modest leader. Previously dominated by an attitude of clubby (‘Ivy League’) exclusiveness and fear of law-suits, McCarthy climbed together with an emerging group of free-spirited, metropolitan, and highly motivated climbers known as the ‘Vulgarians’ or ‘Vulgarian Mountain Club.’ The temperament, expertise, charisma, and tolerance of this gang helped diversify the climbing community to include groups from the City University of New York and younger, more urban and popular milieu generally.

Later in his career as a mountaineer, he continued this open and progressive outlook as a leader of the American Alpine Club. He was crucial in changing the admission criteria of the club, turning its focus to new and younger members, and giving it a renewed emphasis on the basic skills of hard rock and ice climbing. He also followed up on initiatives to both protect and preserve the natural environment, while also working to retain universal access to the climbing and mountaineering patrimony of North America, twin but often contradictory mantras of the US climbing and mountaineering community. McCarthy’s combination of extraordinary skill and a consistently prudent but progressive outlook established him as a senior ambassador of the sport. McCarthy is not only one of the most legendary, but also one of the most appreciated and beloved American mountaineers of the 20th century.

1. Formative Climbing Years at the Shawangunks (‘Gunks’) - The Fifties and the Sixties

When Jim McCarthy first appeared at the Shawangunks, most of the climbers in the area, outside of the few experts such as Hans Kraus and Bonnie Prudden, were ‘involved in clubs such as the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC).’ This was the scene of the sixties where McCarthy was the leader of a bunch of younger radicals who developed this famous crag one hour north of New York City. McCarthy, a well heeled lawyer, was also fit, and without doubt the person after Fritz Weissner, who broke standards . That was on the way to becoming one of the United States most beloved mountaineers of the last seventy years. In the sixties, it was the Appies or the club and the radical Vulgarians. ‘Gunks’ historian Richard Dumais describes this scene in coagulation, one ‘dominated more by bureaucratic and social considerations than by any drive to advance the standards.’ (Richard Dumais, Shawangunks Rockclimbing, p. 44) McCarthy popped in as an apparently unlikely but defining figure in the changes to come. He was from the well-heeled Port Washington exurbs of Long Island in New York City. While still in preparatory school, the 1950 film version of Ramsey Ullman’s best-selling novel 1945 novel The White Tower caused an itch. Now forgotten, this B picture yarned the adventures of a downed bombardier in Switzerland. Glen Ford climbs a famous mountain and makes love to Austrian climberess Alida Valli while escaping from both the Swiss gendarmes, rude German climbers, and those back home who would put him back in a bomber. (The readable Hemingway-format melodrama had become a one and a half star movie despite its respectable cast of the era: Aida Valli, an escaped Austrian refugee, Glen Ford, the American good guy, Lloyd Bridges, the Austrian brownie, Oskar Homolka, the stalwart Swiss Guide, and Claude Rains, the tippling Frenchman. But then there are few good novels or films about climbing, and none with a basically decent and attractive protagonist like the protagonist Ford played.)

McCarthy made his first appearance in the Gunks in 1951 as a freshmen member of the Princeton Mountaineering Club. Paired unluckily with a much better climber on his first day, he was unceremoniously ‘hauled up’ a challenging wide crack named ‘Baby’ (Gran, A Climber’s Guide to the Shawangunks, p. 17). Aftwards, he tossed his psychological gloves on the locale carriage road, and threw body and mind into harder grades on an ever looser tether. The learning curve, however, was tempered by an encounter with the sport’s violence. One of his earliest climbing partners – John Ewing - was killed in 1953 by a leader accident involving rock fall at Sleeping Giant State Park in Connecticut. The sophomore McCarthy had been on a neighboring route. Shook up mentally, he had however already been mentored by the Gunks’ premier climber of the day – Hans Kraus. An immigrant from Trieste and pioneer of sports medicine, Kraus had recognized McCarthy’s talent and drive. Kraus coached his psyched psyche, provided access to the best new climbing equipment, and shared his skill set (Gran, ibid.; see also Accidents in North American Mountaineering, American Alpine Club, 1952). Within a year of starting, McCarthy was himself teaming up with Kraus, whose main climbing partner, the super-legendary Fritz Weissner. Weissner, arguably the greatest of all 20th century American mountaineers, had recently moved to Vermont.

At this time mountaineering and rock climbing on the East Coast was largely dominated by the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC). Worried about lawsuits and protecting the young sport against a sensationalist reputation, the 'Appie' regime was characterized by a baroque system of rules and requirements. Kraus, while respecting the AMC, was both the best climber in the area and one who tended to operate outside their system. McCarthy also adopted this attitude of being ‘independent’, and was by the mid-fifties leading as hard or harder climbs than Kraus into the bargain. With a small group of friends, McCarthy rapidly put in a row of the prettiest routes on the Shawangunk cliffs, and never picked the easy lines. With Kraus and the other independents, they also waged a ‘subtle psychological battle’ against the officiousness and limitations of the AMC. Newness and activity and rumor created a widespread impression about the character of McCarthy’s new ascents out of proportion to their actual challenges.

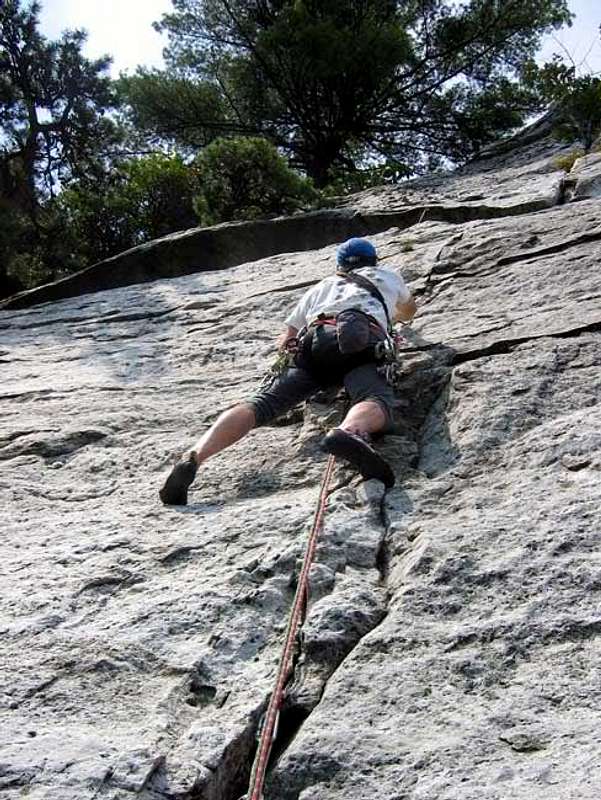

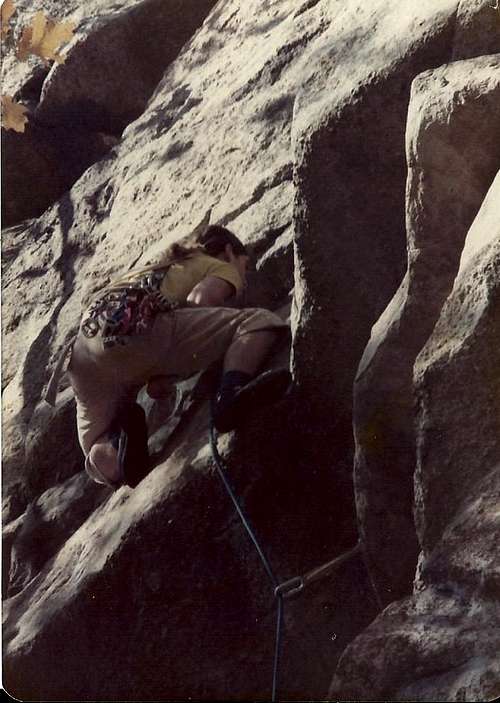

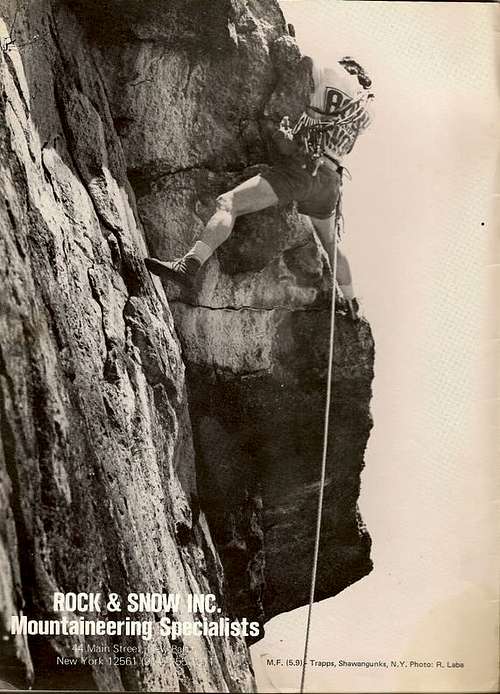

Jim McCarthy lacing up in the Shawangunks in the 1960s era before smooth rubber climbing shoes or Kletterschue.

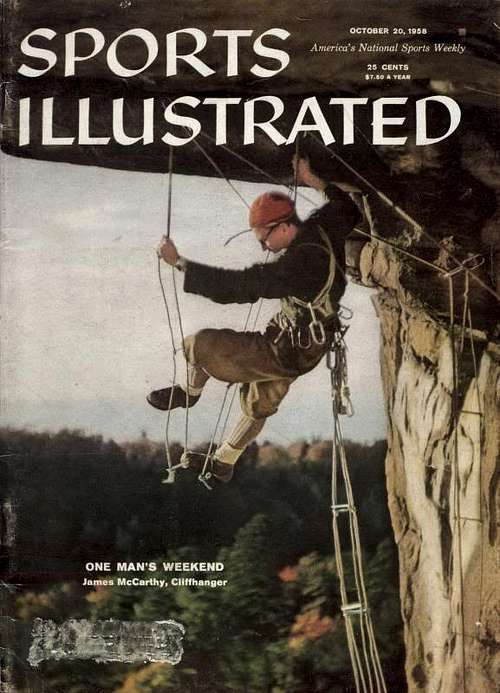

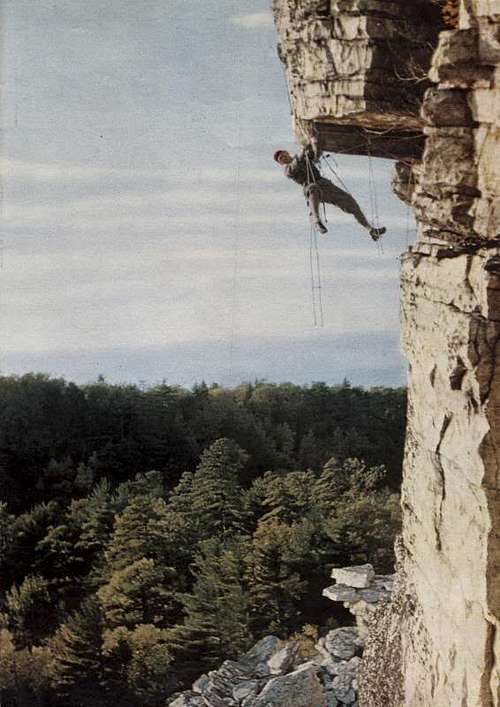

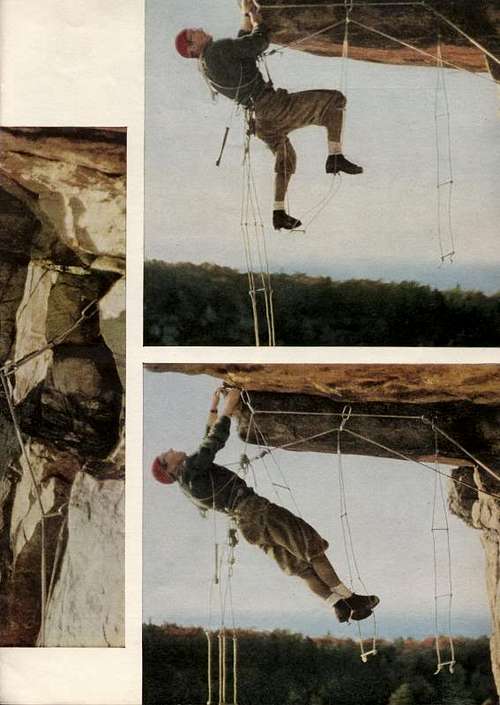

McCarthy had nonetheless outpaced Kraus and everyone else in both the quantity and difficulty of new routes. This began what was to become a remarkable catalogue of first ascents during what the first guidebook called – rightly in the compressed history of American rock climbing – the start of ‘golden age’ in the Shawangunks. McCarthy was miner-in-chief, the ‘leading spirit’ (Gran, ibid., p. 18) Several of first ascents – whether done purely ‘free’ with hands and feet or also with artificial ‘aid’ from things put in the rock to pull on or step on - got a ‘horror’ reputation. This was despite his evident skills with rope work and protection. Cliff sections with intimidating overhanging sections of rock like his route ‘Le Teton’ or the huge ‘roof’ overhang of ‘Foops’ cemented his early reputation. Indeed, though more famous for his reserve, McCarthy is one of the few mountaineers to have made the cover of Sports Illustrated. Part of a photo essay, he is depicted under the caption ‘cliffhanger’, using the double-rope ‘tension’ style to artificially wrangle his way out and around the famous six-foot ‘roof’-style overhang. Described as one with the appearance of a ‘gothic gargoyle on a cathedral spire’, belaying in a small stance over the overhang in the last shot, McCarthy remarks at the end of the photo essay: ‘Climbers are people who relax in thin positions’ (Kim Massie, ‘One Man’s Way to Reach the Summit’, Sports Illustrated, Oct. 20, 1958).

A cover article in Sports Illustrated aid climbing the roof 'Foops' at the Gunks. It was later a famous free climb roof problem.

2. First Forays in the Big Peaks of the American and Canadian West

While mastering such artificial techniques on the local crag that was now officially ‘his’, with or without the authority of Sports Illustrated, McCarthy also followed the lead of Wiessner and Kraus by driving out west to explore bigger challenges. First came an inaugural Summer with Princeton colleague John Rupley in 1954. They followed established routes in the Canadian Bugaboos. But by next year, after collecting his Bachelor’s Degree from Princeton, McCarthy and Rupley no longer went 'west' to repeat others’ lines. Rather, they put in a spectacular ‘classic’ or ‘five star’ artificial route on Wyoming’s Devil’s Tower, one as hard as anything then existing on that famous rock. The chosen path up this iconic plug of volcanic rock was twice as long as the longer Gunks climbs, and no easier (Summit post, Devils Tower, http://www.summitpost.org/devils-tower/routes/p-150309 ) Later that Summer, Rupley and McCarthy met David Bernays and George Austin in the Canadian Rockies; and the four found a complex mixed route of rock and snow to make the first ascent of the Middle Howser Tower in the Bugaboos (Bernays, ‘The Central Howser Spire’, American Alpine Journal (AAJ), vol. 10, no. 1, 1956).

Middle Howser Tower - The McCarthy line follows up the right-center of the middle formation in this fhoto of the Howser Tower group. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

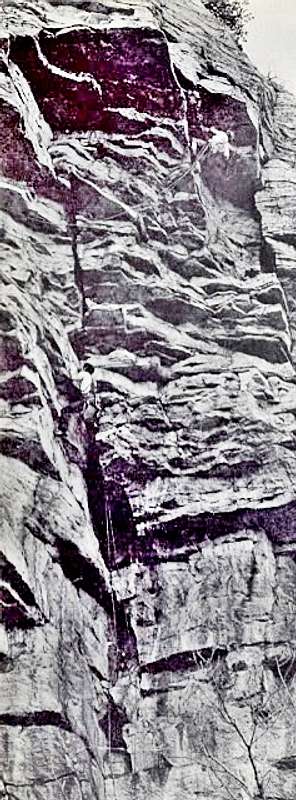

The very next Summer found McCarthy ‘drawn back’ to the Bugaboos – this time with Rupley and Kraus. The team, McCarthy reported, felt themselves ‘climbing at the highest level of their careers.’ Trading leads over some nine hours the three used a combination of free and aid skills to climb the West Face of Snowpatch Spire. Their success, McCarthy emphasized, came from hours of practice establishing speed, flexibility and proficiency with artificial techniques allowing them to ‘seek out space and air on sheer walls and sweeping ridges’ (James P. McCarthy, ‘West Face of Snowpatch’, AAJ, vol. 10, no. 2, 1957) McCarthy and Rupley were not to be stopped here, however. They supplemented their fourth Western summer trip in a row with another difficult artificial route on Devil’s Tower, known today as ‘McCarthy’s West Face’.

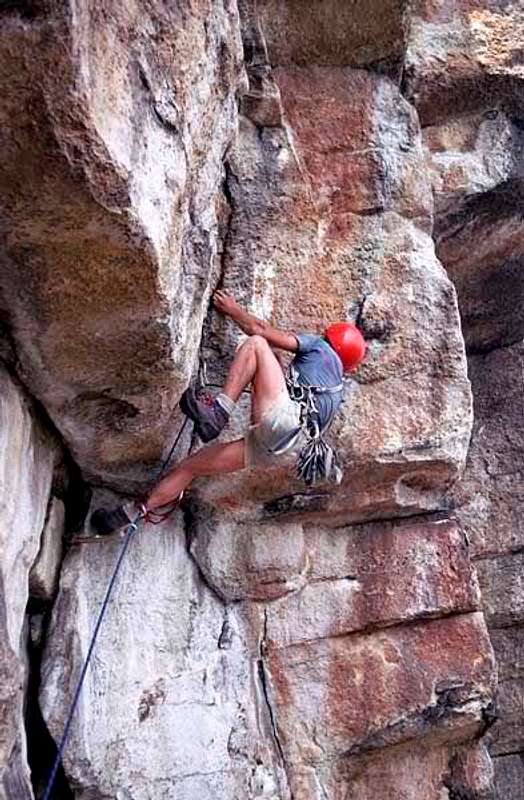

A climber negotiates the second of four overhans on the aesthetic McCarthy West Face of Devil's Tower. Photo Ryan Angelo. The leading digital climbing guide Mountain Project calls it ‘one of the all time classics on the tower.’

McCarthy's Fine Route on Devil's Tower

3. Stirring the Pot in New York with the Self-styled ‘Vulgarian Gang’

If McCarthy saw the future of climbing in those years in terms of the new potential of artificial climbing, the historical record today emphasizes how he continued in the same period to push the limits of pure ‘free’ climbing, that is, with ropes and protection techniques, but without aids to lift the body up the rocks beyond fingers, shoe tips and gymnastic chalk. In 1957, back at the Gunks he established routes of both sorts which became test-pieces of their grade. A ‘test piece’ is a route which, because of a combination of intimidating steep or overhanging character and requirements of strenuous and involved athletic ability, becomes a requirement for later climbers breaking into new difficulties. McCarthy’s were later repeated over and over by later generations of aspiring climbers.

(A ‘test piece’ is a typical or ‘classic’ climb of its grade hard enough to ‘stand for the grade’; and a climber who leads one gracefully has ‘made the grade’, somewhat on the analogy of a new colored belt in the Asian martial arts.)

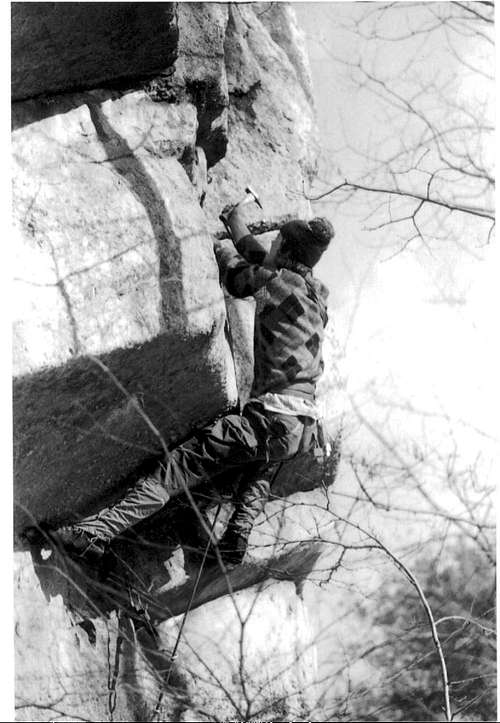

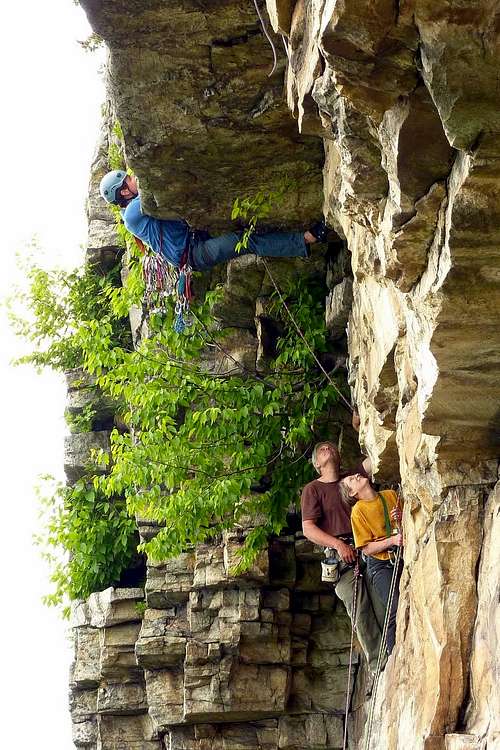

Left: McCarthy's log time parnter Richard Goldstone surmounting the first of two overhangs on McCarthy's 5.9 test-piece 'MF.'

The one named ‘Fat Stick’ got named after intensely fatty mini-pepperoni sausages. It involved a strenuous overhang (precluding retreat once managed) combined with a series of hard to protect and complicated moves above, packaged in a curiously low difficulty rating. The first guidebook, published six years later, referred to this McCarthy-Kraus delicacy in a typical Gunks style – both ominously and humorously – as one tending to regularly ‘eject’ the expert leaders of the day. Even more intimidating (and much less often repeated) was the aptly named double overhang and face problem ‘Yellow Belly.’ This one was put in provocatively right next to Weissner’s more well-known ‘Yellow Ridge’ route. These, like several others, were as hard as any free climb Weissner or Kraus had done in the area.

Besides doing the hardest free climbs of the day, McCarthy also helped pioneer the new game of ‘freeing’ old artificial routes. Having done many routes himself at first with artificial aids, and always experimenting with the latest in techniques and challenges, McCarthy went back to do the same routes without such aids, using the rope only for protection in case of a fall. Many of these so-called ‘first free ascents’, such as the one aptly named ‘Broken Sling’, still have serious reputation decades later.

In 1959, a young Yale student who was not a ‘qualified’ AMC leader was killed climbing, an incident leading to open conflict with the AMC’s reaction, its onerous rules, and fears of lawsuits. McCarthy, as the leading light, also became the de facto figure under which the ‘independents’ opposed the rules and bureaucratic style of the AMC members, known derisively as ‘Appies’ or ‘Tapiocas’. The gang of independents – known in later days, after the remarks of a drunken campfire carouse ironically as the ‘Vulgarian Mountain Club’ (VMC) or ‘Vulgarians’ – insistently pitched their tent in McCarthy’s shadow. VMC was an expression which reflected a more diverse background of the young climbers. They were not exclusively clubby or Ivy League insider groups, but also from New York’s ‘City University’, from non-professional backgrounds, from elsewhere. What united the ‘Vulgarians’ was a willingness to push the standards of climbing, try new techniques, and carry on a wilder, crazier, and more counter-cultural style. In a sport full of both jargon and wise-cracks, the signature was clever dirty language. As fellow Vulgarian Al Rubin remarks: ‘The independents discovered that their outlandish and irreverent behavior on the rocks was a potent weapon in keeping the AMC at bay. After all, how to handle a bunch of young, loud, foul-mouthed hooligans who were also excellent climbers was a daunting problem for the rather straight-laced Appies’ (Quoted from ‘Shawangunks: The Cornerstone of Eastern Climbing’, Supertopo Forum http://www.supertopo.com/climbing/thread.php?topic_id=454584&tn=0&mr=0)

It was the dawn of the 1960s, and as Claude Suhl, perhaps the most hip and exuberant scribbler of the group, later wrote, ‘the Vulgarians were ULTRA-ALL-INCLUSIVE !!! Our stated and enacted mission was to provide a safe haven for all and any Fraternity (or Sorority) rejects in particular, although one could also be welcome if one had such affiliations.’ One could, he adds, ‘also be welcome if one had such affiliations’, as ‘for example successful lawyer McCarthy from Princeton.’ But McCarthy, he notes, was known at the Gunks for ‘publically rejected membership in a Princeton eating club because a good friend of his who was Jewish was denied membership’ (Ibid). Inclusive, profane, wild, crazy and hostile to credentials, ‘the Vulgarians and their fellow travelers were,’ as historian Chris Jones remarks, ‘qualified or unqualified, the best performers.’

The spirit of ‘independence’, it is worth noting, was coded in terms of a narrative of difference from the old ''feudal' model of guides and clients as it was developed by the British gentry during the 19th century. In the post-World-War-II era, the inexpensive surplus gear and the relative lack of a city-gentry, mountain guided model, lead to climbing without guides. This ethic of independence from such commercial relationships was a preferable attitude for climbing combined with early beatnik style to form a the so-called ‘dirt bag’ ethic of road trip independence – best done on the super-cheap in a mobile van with a steady diet of fast food, generic beer, and hard climbing. With the growing inequality and associated other changes in nature of the US social contract since the Ronald Reagan years, such an ethic, while retaining its integrity, has been increasingly challenged by a commercialization which has led back to the ‘gilded age’ ethic comparable in some respects to the Whymper guide and client era of the mountaineering Victorians. This change is most evident perhaps in terms of the business leaders who get in to trouble attempting to ‘purchase’ their way to the top of Mt. Everest. There are baroque lines of clients, log-jams and ‘bottlenecks’ on ‘classic’ climbs of all sorts. (For some views of this picture, see Jim McCarthy, ‘The Last of the Mountain Men,’ Summit, 1971; Jeremy Bernstein, ‘Ascending: Profile of Yvon Chouinard’, The New Yorker, Jan. 31, 1977; Dave Saum, “Ledge Rats in Chamonix’75’”, North American Climber, Winter 1977; Warren Harding, Downward Bound: A Mad Guide to Rockclimbing, Prentice Hall, 1975). David Roberts locates this change with the end of the 1960s, not unlike the song by Don McLean about Rock and Roll: ‘In the 1960s I was lucky enough to climb at the Shawangunks with a group that hovered on the fringes of the Vulgarians. Today, Vulgarian lore is an eastern climbing legend, but in those days the scruffy, bohemian gang was simply the core of a home-grown social scene at a local crag. For a twenty-year-old just leading his first 5.8s, the height of ambition was to converse with Arthur ('Art') Gran or Jim McCarthy. Heroes they might be, but not beyond the society of our own kind…By the late 1960s, as climbing in this country became more chic, a different tone had crept in.’ (See ‘The Public Climber’ in Moments of Doubt, p. 224.)

While some such as Gran, author of the first Gunks guidebook, were climbing at or close to McCarthy’s level, the sheer quantity and committing character of the latter’s creations, combined with his evident embrace of the Vulgarian spirit, kept his reputation intact as the counter-culture took over the Gunks climbing scene. And the counter-cultural character of the Vulgarians is expressed not only in their well-publicized rowdy appearance and behavior, but as well in the names they chose for their new climbs, many of the most notoriously typical McCarthy concoctions. Rather than referring to simple features such as ‘east face’ or ‘north ridge’, McCarthy’s climbs got named ‘Funny Face.’ Or they referred ironically, as in ‘Oblique Twique’, ‘Blistered Toe’, ‘Birdie Party’, or ‘Gory Thumb’, to an effort or controversy that went in to completing them. McCarthy in this period also put in the series of memorable ‘land’ climbs – ‘Birdland’, ‘Never Never Land’, ‘Absurdland’, ‘Roseland’, ‘Turdland’ – which colors this spirit of performance, aesthetics, adventure, hedonism and walpurgis. This new style of naming climbs largely elaborated by the metropolitan characters at the Shawangunks, an hour’s drive from New York City, and which has subsequently been carried on in thousands of climbs done all over the world in the following decades.

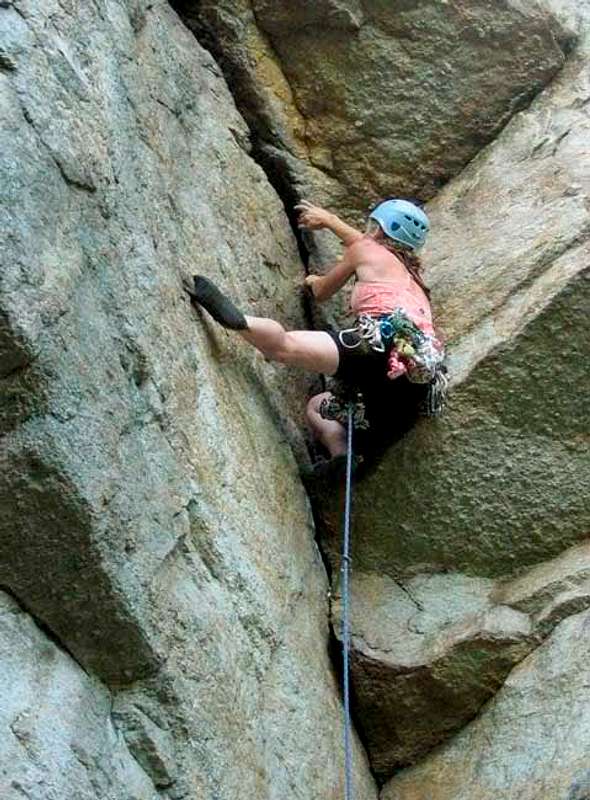

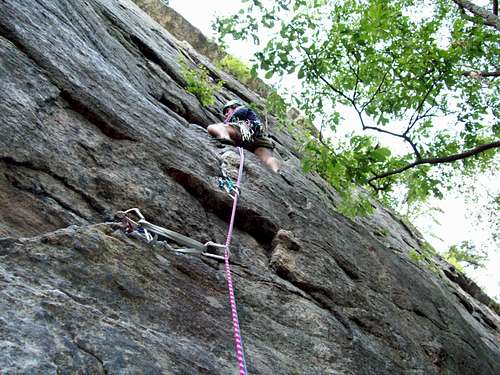

Climber Hovhannes Karagozian is finish up the continuously difficult first 'pitch' or rope length of the 'Birdland' face, a stiff 5.8 and arguably one of the finest of McCarthy's many land' climbs, this one named after Charle Bird Parker.

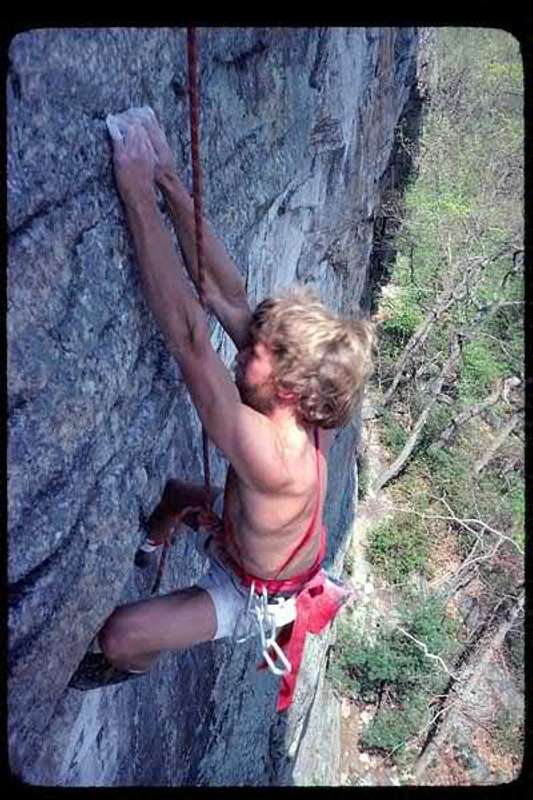

4. Breaking Open the Standards Framework during the 1960s

In the Summer of 1960, McCarthy went West, where he teamed up with Dave Dornan and noted Yosemite climber Yvon Chouinard to climb the demanding and long ‘No Escape Buttress’ on Mt. Moran in the Teton Range of Wyoming. Chouinard, a blacksmith, had learned the technique of making hardened steel pitons of chrome-molybdenum alloy in ever more useful shapes and sizes. McCarthy brought some back East along with mail-order forms. Meanwhile the Europeans had recently introduced soft rubber soled and tight-fitting Klettershue (‘Climbing Shoes’), known in the US by their German word, though developed originally in the forests of Fontainebleau France by Pierre Allain. With this new kit, McCarthy began perhaps the most famous and productive period of his long career - as one of those ‘responsible for a remarkable upgrading of…standards.’ At the time, grading difficulty was done predominately with two systems: in the Europe with its Union of International Alpine Associations or ‘UIAA’ standard in Roman numerals and in the evolving Yosemite Decimal System of fractionalized Arabic numerals. In both, it was assumed after a certain point of free climbing difficulty, one would natural resort to artificial techniques; and thus both systems ended at finite limits. There was supposed to be nothing harder than a UIAA VI, while in the US the ‘fifth class’, before the artificial ‘sixth class’, was assumed to have a finite scale (marked in decimals – 5.0, 5.2, etc. from easiest 5.0 to hardest 5.9. But with the new pitons and the Vulgarian competitive spirit, the climbs kept getting harder and harder with nowhere for the grading system to reflect this. McCarthy, in 1960, referred in this regard to easy, medium and hard ‘sixes’ in the UIAA form, refusing to claim the ability to do ‘hard sixes' (Franz and Gene Mobling, ‘Those Remarkable Cliffs Known as the Gunks’, Summit, Sept. 1960, pp. 8-11). Not until nearly a decade later did a (nonsensical) 5.10 and then 5.11 rating get to the books; and by this time the higher ratings encompassed such a range of difficulty that they are now conventionally broken into the small case letters ‘a’ through ‘d.’ While McCarthy was busy pushing the limits of free climbing, he like so many others, wanted to avoid ‘over rating’ his achievements, and so kept them underrated – what is known today colloquially as a ‘sand bag.’ McCarthy may have looked like a six-foot version of Zeppo Marx. But he played the ratings game like Zeppo’s older brothers, and possessed the skills to do so. As a popular mountain magazine of the time noted, McCarthy ‘certainly doesn’t look the part’ of such a ‘crafty crag rat.’ His ‘tired, reflective face, thick horn-rimmed glasses, and long-sleeved shirts hide his simian arms. Jim looks like a slightly shopworn, successful New York lawyer, exactly what he is studying to be. He trains in Karati (the Japanese art of unarmed bone-breaking) and gymnastics to keep in shape. I have seen him hang by his arms for minutes on end, his feet completely free in the air, while he examined possible combinations on an overhang.’

In this environment, McCarthy began pushing hard at Zeno’s paradox of 5.9 and its supposed absolute limit. He managed the strenuously overhanging ‘Bonnie’s Roof’ without aids, calling it a mere 5.8, and then preceded to put in a series of hard sixes or 5.9s: the straight-up ‘Apoplexy’ located right where the cliff’s carriage road turns into a Gunks’ Times Square; a muscular free-ascent of his aid-route ‘Roseland’; the last of the ‘land’ climbs - a super-scary and hard ‘Land’s End’; and his most famous and oft-repeated test-piece, called simply ‘MF.’ This latter was reputedly – in the vulgarian language – an abbreviation for ‘McCarthy’s Folly’ or ‘McCarthy’s Finest.’ Historians Laura and Guy Waterman observe that it was ‘the first universally acclaimed 5.9 at the Shawangunks’ and ‘has remained ever since the classic of its grade, the 5.9 to do.’ MF had an unrelenting standard of difficulty right in the middle. It had consistently enjoyable and complex moves. It had an impressive location smack in the center of one of the steepest and smoothest wall-like sections of the long Trapps cliff. All together, ‘MF’ from its day of existence proudly garnered its ‘historical importance’ (Laura and Guy Waterman, Yankee Rock and Ice, Stackpole Books, 1993, p. 176).

‘MF’ , however, was a start. By the time the year was out, McCarthy had done virtually every climb on ‘that wall’ – the steepest and most intimidating single section of the main cliff at the Shawangunks. It is a section known today as the ‘Mac’ or ‘McCarthy Wall.’ McCarthy hardly rested. The next year he broke into the 5.10 realm with the fearsome twin cracks ‘Retribution’ and ‘Nosedive’, along with another in that grade, ‘Tough Shift. ’ The first of these three, generally regarded as the first of its grade in North America, and, right on the local thoroughfare, is likely as well one of the most repeated. Between 1960 and 1964, McCarthy had done at least thirty new routes in the 5.7-5.10 class while bringing in the 5.10 grade (Richard Dumais, ‘Shawangunks: The North-East’s Most Popular Crag’, Mountain 21 (May, 1972), Included were standouts like ‘Black and White’ in Quebec; and in the Gunks, the spectacular ‘Sound and Fury’, ‘Matinee’, and ‘Never Never Land’; the 5.10 test piece ‘Co-Existence’, the notoriously bold ‘Grand Central’, and the poorly protected ‘Shitface.’ McCarthy had now achieved national recognition and become a leading figure in the American Alpine climb. In the process (along with his fellow Vulgarian hard man Art Gran and others), he had brought ‘respectability to the Shawangunks in the eyes of the California and Colorado climbers, many of whom now made pilgrimages to the hitherto little-heralded New York scene’ (Waterman, ibid.; the cutting-edge Alpinist Jim Donini remarks in this regard: ‘He was kind and gentle when Yosemite legends came to the Gunks in the 1960s and had their lunch handed to them.’)

Right, The tall and powerful John Bragg, later famous for surmounting the largest 'roof' overhang in the Gunks, working away at what is probably McCarthy's most famous 5.10 test piece, 'Co-existence.' Photo: Richard Goldstone.

5. New York City Skills Combined with the Best of the West – McCarthy on Big Walls in Colorado, Alberta, North-West Territories, and Alaska

By 1962, McCarthy was back out West where he played a role in pushing standards on the biggest mountain faces in North America that compared with his work back East pushing free climbing standards. First stop was Colorado. There McCarthy, in the words of historians Dudley Chelton and Bob Godfrey, played a ‘brief but energetic role’ in early ‘Big Wall’ climbing – that is, multi-day climbs of huge vertical faces of a 1,000 feet or more. McCarthy and another Easterner Will Bassett teamed up with Colorado legend, Layton Kor and sidekick Tex Bossiter. After a raucous night in Boulder where Kor pulled the exploding cigar trick on the good-natured McCarthy, they became involved in an attempt on the ‘Yellow Wall’ on the fabled Diamond of Long’s Peak. In the end, Kor and Bossier finished this alone, as McCarthy and Bassett became ill. This was not the only thing Kor and McCarthy failed on. McCarthy was also along with Kor on the first attempt of the 1700 foot long ‘Russian Arete’ in the difficult and intimidating gorge of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison – a locale featuring notoriously uncertain rock and a horrid descent into dark and gloomy abyss from which up is the only practical retreat. Later in 1963, McCarthy joined Kor and Bossiter on an even more serious and difficult artificial route in the depths of the Black Canyon. The route that led them out, named the 2,000 foot long ‘Diagonal’ – scary, complicated, friable – was done at the highest level of artificial climbing at the time, and though now free at 5.12, is rarely repeated with or without aids.

Nonetheless, the team had failed to find in Colorado what Kor was looking for: a Grade VI. Kor was searching for a climb up a large vertical feature where a regular party must spend three or more days on the effort, comparable to the big faces like the Dru or Grandes Jorasses in Chamonix or Half Dome or El Capitan in Yosemite. Through the American Alpine Club, however, it was McCarthy who wrangled a ‘grant’ to find just such a wall in Canada. The AAC directive: ‘pick an objective that will contribute to the development of American climbing and gather the strongest group of technical climbers available.’ The object chosen was the giant Southeast Face of Mt. Proboscis in the Logan Mountains of Canada. The team included not only Kor, but also Royal Robbins, perhaps the greatest of all the Yosemite Big Wall climbers, and Robbins’ friend Richard McCraken.

The face of Mt. Proboscis. Photo: McCraken

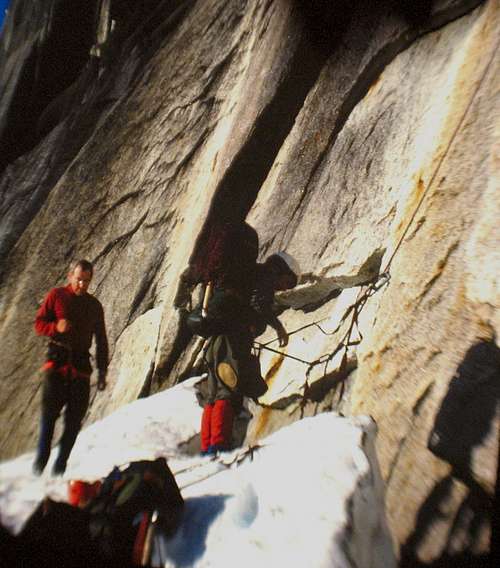

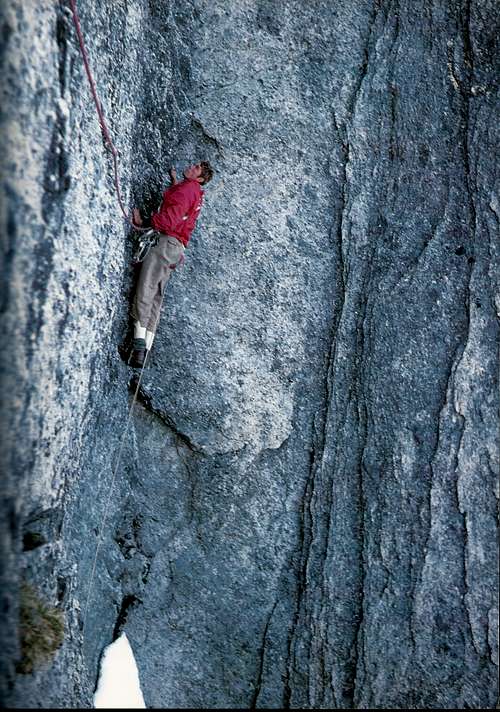

Layton Kor leading on Mt. Proboscis. Photo: McCraken

After one false start halted due to weather, the team of four, working in pairs, surmounted a sea of artificial difficulties, a wild fall by Kor which yanked McCarthy’s hands ‘rather messily through carabiners’, and three stormy nights on the giant wall to finish up a very serious route that was most definitely a ‘Grade VI.’ The party called it with justice ‘one of the most difficult technical rock climbs ever done under remote alpine conditions, as well as one of the most elegantly direct routes that one can hope to climb’ (James P McCarthy, ‘The Southeast Face of Proboscis’, AAJ, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1963).

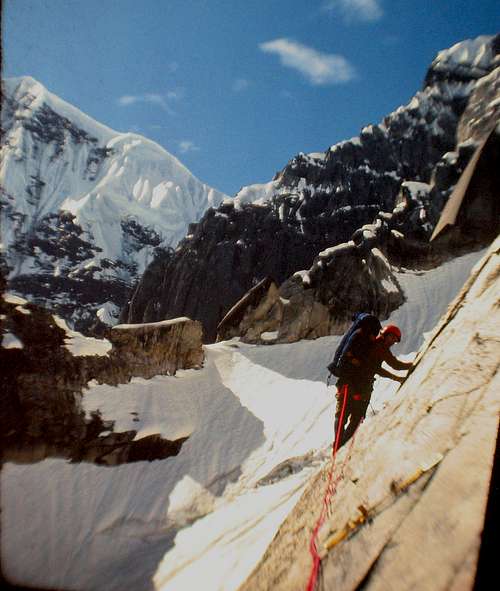

With regards to McCarthy’s next major ascent, one climber recently wrote: ‘The best rock climb in the world? Most routes which take this moniker seem insignificant compared to the Southeast Face of the Lotus Flower Tower.’ Two years after the first Grade VI big wall in alpine North America, he had convinced a new crowd to return to the ‘Cirque of the Unclimables’ in which Proboscis was located – Harmon (‘Sandy’) Bill, photographer Galen Rowell, and engineer and innovator Tom Frost. As Bill retells: ‘The Prophet, James McCarthy, had told of an arcadia of perfect weather and spectacular climbing in the Logan Mountains of the Selwyn Range of the North West Territories.’ Once again, a long drive – this time in Tom Frost’s VW bus known as the ‘red baron’ – and a bush flight brought the crew to McCarthy’s favorite ‘cirque’: ‘a land of huge glaciers with outsized Yosemite spoken through them’ as pictured by teammate Galen Rowell – ending in a beautiful 2,000 ft. formation, vertical and clean, with a fabled single crack rising straight up to the top once one climbs up several hundred feet of ‘open books’ as overture (Galen Rowell, ‘The Great Canadian Knife’, AAJ 16 2 1969).  Left, The 'Wall of Forgetfullness' or Lotus Flower Tower - described by big wall climber Doug Scottas a route with a 'legendary perfect cxrack cleaving the face for much of its length' - follows a line straight up the middle of the large toothed formation.. One of the finest Grade V climbs in the world. Photo: Tom Frost.

Left, The 'Wall of Forgetfullness' or Lotus Flower Tower - described by big wall climber Doug Scottas a route with a 'legendary perfect cxrack cleaving the face for much of its length' - follows a line straight up the middle of the large toothed formation.. One of the finest Grade V climbs in the world. Photo: Tom Frost.

After climbing the one single crack for a day and a half, Bill describes a ‘golden line.’ Lazy nights in hammocks merged with ‘lounging in the warm sun’, all while the leader by turns enjoys ‘the near perfect rock.’ We have, so Rowell’s reverie, ‘eaten lotus and known its power on this Wall of Forgetfulness.’ His partner Frost added: ‘it was the ultimate expedition: good friends, good mountains, good weather’ (Harthon Bill, ‘The Wall of Forgetfulness: Lotus Flower Tower, Logan Mountains’, AAJ, Vol 14, No. 1, 1964). Rowell and McCarthy returned to the Cirque in the Summers of 1972, though bad weather prevented any ascents. Next year they returned together with Joe Bridges, Sandy Bill, and Laura Brant (whom McCarthy later married) in 1973. This time kidney stones compelled Jim’s early departure, but not before he and Rowell put a challenging line up the South-East Ridge of Mount MacBrien. In 1975, McCarthy joined Bridges again, along Tom Fischer and new climbing phenomenon Henry Barber, for an attempt on the huge East Buttress of Mount Johnson in the Alaska Range. After ten rope lengths, they ran into dangerous rock and realized that without equipment for drilling holes, there was noway up the huge headwall above. They turned back aftera sizable adventure.

Jim Mcarthy below following the tenth pitch of an attempt on the East Buttress of Mount Johnson in the Alaska Range with Tom Fischer, white helmet, and Henry Barber (lower right), Photo Joe Bridges.

For McCarthy energy, such usual expeditionary setbacks were thus merely a kind backdrop. McCarthy this whole time had also been hard at it putting up stiff climbs in the Shawangunks – ones with famous names such as ‘Try Again’, ‘Transcontinental Freeway’, ‘Men at Arms’, ‘Balrog’ and ‘Happiness is a 110° Wall.’ The duration and sheer continuity of this catalogue of new routes here are largely the evidence with which McCarthy is often credited with playing a or the ‘key role in the advancing standards’, that is ‘advancing standards of every grade from 5.8 to 5.11’ – and most especially in at a time and in a place where many in the local climbing community viewed such a standards-busting attitude as ‘subversive.’ Always innovating, McCarthy was present at the ‘birth’ of modern ice climbing. He was the first to use front pointed crampons to climb toe-first up the steep hard-ice Pinnacle Gully on Mt Washington, eschewing the old method of laboriously cutting steps (Yvon Chouinard, Climbing Ice, Sierra Club, 1978, p. 33).

McCarthy ice climbing with front-point technique he pioneered in New England, on Baird's Wall in the Shawangunks in 1973. Photo: Joe Bridges.

He also managed, together with essayist Lito-Tejada Flores, to do the the first South to North traverse of the Tetons. One guide describes this ‘grand tour of one of the most fantastic American mountain Range’ as a challenge requiring ‘fitness, boldness, route-finding skill and endurance.’ The tabulation of superlatives is testimony to one of the reasons McCarthy is one of the most admired of American climbers: he was not only terribly good, but he had a remarkable eye for picking the very best, steepest, cleanest, most aesthetic way up the cliff in question. He also was congenial enough to work with the best climbers from other North American hot spots like Colorado and California. Migrating from one ‘super group’ to the next, McCarthy produced one great work after another, most of which are established and repeated over and over. The result is that generations of climbers know them and respect him.

One of McCarthy’s characteristics – which suggests why he later pressed the mountaineering establishment to openness for ‘sport climbing’ even as he made repeatedly cautious remarks about excess publicity and ‘extreme’ behavior – was a penchant for falls caused by pushing the envelope. A brief examination of the literal meaning of the names in list of his first ascents makes the point, as do remarks and anecdotes of his peers. Kor notes that he had to back off an attempt on the ‘Russian Arete’ in the Black Canyon ‘when a loose block broke off and hit him in the thigh.’ Kor continues: this route is ‘not the most solid thing I ever climbed. That’s why we gave it the name – it’s like Russian roulette.’ Most famous are two incidents involving West Coast climbing legend Chouinard, who reputedly never fell on the lead rope. McCarthy led Chouinard during the latter’s first visit to the Gunks in the early 1960s to his own ‘Never Never Land.’ The site of an earlier show down with Art Gran, McCarthy’s only real local rival in the early 1960s, McCarthy wanted to show Chouinard a hard Gunks face climb. After leading up to the first ledge and being unsecured, he slipped. His belayer quickly re-grabbed the rope and managed to stop McCarthy – near the ground after a 70 foot tumble. ‘Seemingly unperturbed by his narrow escape...[h]e fixed his eyes on the startled Chouinard and majestically intoned, “Welcome to the Shawangunks.’” By the late 1960s, McCarthy was in Yosemite Valley making an attempt at the famous “Nose” Route on the 2,800 foot El Capitan. Following the new style, he was trying to hammer in his pitons very lightly of avoid permanent rock damage. He took a serious fall, broke a bone, and had to be rescued from the first main ledge. Leader of the rescue party was Chouinard, who greeted him with ‘Welcome to Yosemite’ (Jones, op cit., pp. 285-6.). Not all of the incidents banged up McCarthy. On his mentor’s Hans Kraus’s penultimate first ascent, a rope caught in a crevice caused both the front and the back person on the three rope party to yank so much that in confusion they actually damaged the ribs of the middle person on the rope. Kraus’s humor was as dry as Chouinard’s, and in the wake of the ‘pretty funny’ incident, as Kraus called it, the route was named ‘Rib Cracker’ (Susan B. Schwarz, Into the Unknown: The Remarkable Life of Hans Kraus, Universe Books, 2005, pp. 189-90.)

6. A Senior Ambassador of North American Climbing

As the 1970s dawned, McCarthy produced fewer routes. The fifty-something spent more time on his legal practice, and more time with the American Alpine Club – as one of the more influential, involved and appreciated figures in the climbing community. In this regard, his consistent ability to work with all different sorts of climbers, and especially younger ones, reappeared in a different hue. An East-coast lawyer with long term ties to the AAC, McCarthy had often already played this role. He had, for instance, helped to pick out a team for a secret CIA mission for instance to place a nuclear power observation device on a Himalayan peak after the Chinese exploded their first nuclear device. (See M. S. Kohli and Kenneth J. Conboy, Spies in the Himalayas, Univ. of Kansas Press, 2002, pp. 27-29.) He had and continued to provide legal advice in the thorny relationships of small-time climbing businesses to larger corporations. He helped negotiate the historical changes caused by ‘extreme’ sports styles that arose together with a new professional climbing model – on Everest and elsewhere – of sponsorship and expensive guides. Mountaineering diversified and overlapped – with bouldering, sport climbing, ‘buildering’ or urban climbing, ‘deep water’ ropeless climbing on high cliffs over bodies of water, big mountain skiing and snowboarding, slack lining, ropeless or ‘free solo’ ascents of the biggest skyscrapers and the biggest cliffs, scary rock ascents with ice climbing gear on hands and feet (‘dry tooling’) in order to 'get' to the icy sections, paragliding, BASE jumping, squirrel suits, and the like. Albeit with a traditional respect for doing anything and everything the environmentally respectful and hard way, McCarthy continued to use the attitude of independence he established with the Vulgarians as a framework to keep the climbing establishment in touch with the ongoing transformation of society and the development of his sport within it. He was, as a leading magazine editor emphasizes, ‘the first to push the AAC to reach out to the sport climber community’ (Oscius, AAC statement). He recognized progress and change in order to keep up with it, a task served by his lawyer’s negotiation skills.

Below: Jim McCarthy talks with former Vulgarian Brian Carey at a 2008 Shawangunks reunion at the Mohonk Trust Visitors' Center. Photo: Joe Bridges.

McCarthy gets the credit when credit is mentioned for keeping the American Alpine Club in tune with the under-thirty cohorts who are naturally the prime performers. He established a ‘youth award’, eliminated clubby old-school barriers to membership. He pushed the chair-bound organization to get involved when the main climber’s campground in Yosemite – a renowned international Hooverville – was threatened with destruction in the mid-1990s because the AAC had initially ignored the issue while the Access Fund did so comprehensively. With the development of ‘sport climbing’ modeled on indoor gymnasiums and bolt-drilling on rock otherwise unsafe to climb upon, he negotiated the opposition it caused from ‘traditional’ climbers unappreciative of this new style. Even in his eighties, he appears in the climber news channels inspirationally – if only with phone calls to a group of young women on Mt. Proboscis working to free climb his old big wall test piece from 1963. See Emily Stifter, et al., ‘Woman at Work: A Film’ at ‘AAC Climbing Blog’, http://inclined.americanalpineclub.org/2011/05/women-at-work-video/). What remains are a list of spectacular adventure lines for future generations and a reputation as perhaps the only completely un-criticized over-achiever in the history of a naturally controversial sport.

7. First Ascents (FA) and First Free Ascents (FFA)

Unless otherwise noted these were done at the Shawangunks. It is a long list.

1954 Funny Face (5.5, FA), with Tim Mutch

1954 Jim’s Gem (FA), with Stan Gross

1954 Gory Thumb (FA), with Dave Bernays

1954 Sundance (5.5, FA), with John Rupley

1954 No Glow (5.6 A1 FA), with Tim Mutch

1954 The Womb Step (5.7, FA), with Bob Larson

1954 Simple J. Malarkey (5.7, FA), Seneca Rocks, West Virginia, with Arnold Wexler

1954 Co-op (FA), with Dave Bernays

1954 Fillipina (5.7 A1, FA), with Stan Gross

1955 Le Teton (FA), with Stan Gross

1955 Foops (FA), with John Rupley

1955 McCarthy West Face (III, 5.8 A3, FA), Devil’s Tower, Wyoming, with John Rupley

1955 East Face, Middle Howser Tower, Bugaboos, Canada (III, 5.7 A2, FA of tower by any route), with John Rupley, David Bernays, and George Austin

1955 Try Again (5.7A2, FA), with Hans Kraus; 1967 (5.10, FFA), with Richard Goldstone and Ray Schrag

1955 Double Crack (FA), with Hans Kraus; 1958 (5.8, FFA), with Jim Geiser

1955 Strange City (FA), with Hans Kraus and Stan Gross

1956 Alley Oop (5.7 & shoulder stand, FA), with Hans Kraus and Stan Gross

1956 Cakewalk (5.7, FA), with Hans Kraus

1956 Kraus-McCarthy Route, West Face of Snowpatch Spire, Bugaboos, Canada (IV, 5.8 A2, FA), with Hans Kraus and John Rupley

1957 Yellow Belly (5.8+, FA)

1957 Fat Stick (5.8, FA), with Hans Kraus

1957 Directississima (5.7 A1, FA), with Hans Kraus and John Rupley

1957 Pas de Deux (FA), with Jack Hanson

1957 Oblique Twique (5.8+, FFA)

1957 McCarthy’s North Face (III, 5.7A2, FA), Devil’s Tower, Wyoming, with John Rupley

1958 Roseland (FA), with Hans Kraus; 1960 (5.9, FFA)

1958 Foops (FA)

1958 Broken Sling (5.8, FFA)

1958 Katzenjammer (5.7, FA), with Jack Hanson

1958 Birdland (5.9, FA)

1958 Ventre de Boeuf (5.8 A1, FA), with Claude Lavallee and Jim Andress

1958 Blistered Toe (5.7, FA), with John Wharton

1958 Snooky’s Return (5.8, FA), with Dave Craft

1959 Drunkard’s Delight (5.8-, FA), with Jim Andress

1959 Never Never Land (FA), with Art Gran and Dave Craft; (5.10, FFA), with George Hurley

1959 Turdland (FA), with Jack Hansen

1958 Birdcage (FA), with John Rupley and Jim Andress

1958 Garden of Allah (5.7 A1. FA), with Hans Kraus and John Rupley

1959 Birdie Party (5.8 A2, FA), with Doug Tompkins

1959 White Corner (FA), with Phil Jacobus

1960 Airy Aria (5.8, FFA)

1960 Land’s End (5.9, FA), with Art Gran

1960 Absurdland (5.8, FA), with George Bloom

1960 MF (5.9, FA), with Claude Suhl and Roman Sadowy

1960 Apoplexy (5.9, FA)

1960 Farewell to Arms (5.8, FA), with Al DeMaria

1960 No Escape Buttress (IV, 5.9), Mt. Moran, Tetons, Wyoming, with Yvon Chouinard and Dave Dornan

1961 Bonnies’ Roof (5.9, FFA), with Richard Williams

1961 Rib Cracker (5.8+, FA), with Hans Kraus and Werner Bishof

1961 Retribution (5.10, FFA)

1961 Nosedive (5.10, FFA)

1961 Baskerville Terrace (5.7+, FFA)

1961 Tough Shift (5.10, FA), with Ants Leemets

1961 Westward Ha! (5.7, FA), with Harry Daley and Hans Kraus

1962 Ape Call (5.8, FA), with Jim Andress and Ants Leemets

1962 Broken Sling (5.8+, FA)

1962 Black and White, Weir Cliff, Quebec (5.10+), with Claude Lavallee

1962 Co-Existence (5.8 A1FA), with John Hudson and others; 1967 (5.10, FFA), with Richard Goldstone

1962 New Frontier (5.8 A1, FA), with Ants Leemets

1963 Shitface (5.10 R, FA), with Jim Andress

1963 Sound and Fury (5.8, FA), with Richard Williams

1963 Groovy (5.8+, FA), with Jane and Bob Culp

1963 Grand Central (5.9, FFA)

1963 Criss Cross (5.10-, FFA)

1963 Matinee (5.10, FA), with John Hudson

1963 Raunchy (5.8, FA), with Bill Gouldner

1963 Beyond the Fringe (5.9X, FFA), with Doug Tompkins

1963 Directissima (5.9. FFA)

1963 Comedy in Three Acts (5.8 A3), with Ants Leemets and Richard Williams. All three participants fell in succession trying to manage the first rope length.

1963 Commando Rave (5.9, FA), with John Hudson

1963 Mac-Kor-Wick (5.8, FA), with Richard Williams and Layton Kor

1963 This Petty Pace (5.9, FA), with Richard Williams

1963 South East Face Original Route (VI, 5.8A4, FA), Mt. Proboscis, Cirque of the Unclimbables, Nahanni National Park Preserve, Canada, with Layton Kor, Royal Robbins and Richard McCraken

1963 The Diagonal (V, 5.9 A5), Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Colorado, with Layton Kor and Tex Bossier

1964 Sling Time (5.7 A2, FA), with Richard Williams

1964 Hardware Route (5.8, FA), with Layton Kor and Matt Seddon

1964 Sticky G Direct (5.7, FA), with Richard Williams

1964 Mud, Sweat and Tears (FA), with Richard Williams

1964 Stubai to You (5.9, FA), with Richard Williams

1964 B. M. (5.8, FA), with Richard Williams and Brian Carey; 1964 FFA with Layton Kor and Matt Seddon

1964 Realm of the Fifth Class Climber (5.9, FA), with Hans Kraus, Art Gran and Richard Williams

1964 Frustration Syndrome (5.10, FA), with Richard Williams and John Reppy

1965 Transcontinental Nailway (5.10, FFA)

1965 Lito and the Swan (5.9 PG-R, FA), with Lito Tejada-Flores

1965 Mac-Reppy (5.8, FA), with John Reppy (later much harder do to rock fall)

1966 Eastertime Too (5.8, FA), with Richard Williams and Don Hudson

1966 April Showers (5.9 A3,FA), with Ants Lemeets and Richard Williams

1966 Men at Arms (5.10, FA) with Richard Williams

1966 J’accuse (5.9 A1, FA)

1966 Grim-Ace Face (5.9+, FA), with Royal and Liz Robbins

1966 Nemesis (5.10 R, FA), with Richard Williams, John Hudson, Phil Jacobus and Steve Larson

1966 To Have and Have Not (5.8 A4, FA), with Pete Carmen

1966 Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, 5.8 A2, with Richard Williams

1966 Teton’s ‘The Grand Traverse’ North to South from Teewinot to Nez Perce (V, 5.8), Teton Range, Wyoming, with Lito Tejada-Flores

1966 Beatle Brow Bulge (5.4 A3, FA), with Matt Hale and Jim Alt

1966 Ruby Saturday (5.9, FA)

1967 Balrog (5.10, FA), with Richard Goldstone

1967 Higher Stannard (5.9-, FA), with John Stannard

1967 Son of Bitchy Virgin (5.6R, FA), with John Reppy

1967 Happiness is a 110° Wall (5.9 A2, FA), with Art Gran

1967 Psychosis (5.9+, FFA), Pok-o-moonshine, Adirondacks, NY, with Richard Goldstone

1967 Fastest Gun Off-width Variation (5.10, FA), Pok-o-moonshine, Adirondacks, NY

1968 Credibility Gap (5.6, FA), with Richard Williams and Joe Kelsey

1968 Generation Gap (FA), with Richard Williams

1968 Schlemiel (5.10, FA), with Burt Angrist

1968 Lotus Flower Tower (VI, 5.8 A2), Cirque of the Unclimbables, Nahanni National Park Preserve, Canada, with Tom Frost and Sandy Bill

1969 Proctoscope (5.9+, FA), with Richard Goldstone

1970 Pinnacle Gully, Mt Washington, New Hampshire (FA with front points)

1971 Something Boring (5.9 X, FA), with friends

1971 Never Say Never (5.10 X, FA), with Richard Williams

1973 South-East Arete, Mount MacBrien (IV, 5.9), in Logan Mountains, Canada, with Galen Rowell

1975 Prusik Peak (First Winter Ascent), with Dave Anderson, Cal Folsom, and Tom Linder

8. Anecdotes and Remarks about Jim McCarthy

Potentially apocryphal dialogue between McCarthy and Claude Suhl

“This brings up my all time favorite made up but true story. Mac[Carthy] was sitting under April Showers tying has shoes when he looked up. He said to Claude [Suhl], ‘Do you suppose that roof has gone? ‘ Thumbing through the guide Claude says, ‘Yeah, Jim. It has gone.’ Jim says, ‘Who did it?’ Claude replies after a pause, ‘Jim. You did it.’ After a somewhat longer pause Jim says, ‘Does it say how hard it is?’"

- John Stannard, in ‘Shawangunks: Cornerstone’, op cit.

Unnamed tort lawyer who sounds suspiciously like McCarthy

“The climbing environment in an area can be created or changed in an instant. One moment that helped form my perception of the Gunks was a comment by a climbing lawyer, whom I will not name, just after winning a tort case. He said, ‘Once more, justice has been defeated.’

- John Stannard, in ‘Shawangunks: Cornerstone’, op cit.

Poetic License of McCarthy’s Best Known Partner from the 5.10 Era

“One year, McCarthy went out on a 90 degree 90% humidity windless summer day to do what anyone seeking a break from the oven-like conditions would do: burn the brush around his house. So he takes a can of gasoline, saturates a large area of brush, waits a bit for the fumes to fully envelop the area, and then, standing in the middle of it, lights a match. Measurements taken later of the take-off footprints and landing butt-print suggest that Jim was then and probably still is the world's record-holder for the standing backwards broad jump. After weeks of non-stop celebration of this feat of athletic prowess, hosted by the Columbia Presbyterian burn unit, Jim emerged, somewhat pinker than before, and also, thanks to enforced inactivity and hospital cuisine, just a tad on the heavy side. For his rehabilitation activity, he decided to join a group of us in the Needles in South Dakota. Unfortunately, the Great Designer had not considered, when drawing up the Needles nubbin-load specifications, that anyone of Jim's post burn-unit avoirdupois would be entrusting their considerable heft to those tiny crystals. And so it was that the pine forests of Custer echoed with the snap, crackle, and pop of nubbins giving way under Jim's attempts at upward progress. Entire faces were left glassy smooth by his repeated efforts, mostly in vain, to find something to stand on that would hold him up long enough to take the next step. And let us now speak of those who undertook to belay Jim on these forays into the realm of pinnacle-polishing. Imagine them seated on top of the spire du jour, sitting on a cushion of ever-so-unpolished Needles granite, like mystics on their bed of nails, awaiting that hemorroidal impact as Jim's footholds sheared, eyes beseeching the heavens for a quick end to the suffering they were about to endure. Both the Needles and his partners were saved from extinction by the fact that the rehabilitation effort was successful, Jim's weight melted away, the nubbins stayed under foot, Jim rose up as in the days before, and all was right with the world again.”

- Richard Goldstone, ‘Shawangunks: Cornerstone, op cit.

“Climbing and dissipation always went hand in hand at the Gunks. The evening bar scene was as much a part of the social life as the camaraderie on the cliff…When I was a freshman, the gods were Jim McCarthy and Art Gran, and it was at Emil’s Bavarian Bar that I first tasted the inexpressible joy of having them deign to speak to me. There has always been a fine tradition at the Gunks of established top dogs taking the green rookies out to climb. That cross-generation rapport, combined with the festive night life, helped produce the rich social climate for which the Gunks are famous.”

- David Roberts, ‘Boulder and the Gunks’, in Moments of Doubt, p. 212

8. Photo Gallery - Additional McCarthy Moments & Folks Climbing McCarthy Routes

Broken Sling - Jeff Mekolites has worked though the hard part of the technical 'Broken Sling.' Photo Greg Allen.

Drunkard’s Delight- A climber has passed the ankle-breaking beginning of the crux of 'Drunkard's Delight.' Photo John Hoffman

McCarthy doing handstand on porch of his former Accord weekend home, Dec. 1971 – During the early to mid-1970s, McCarthy, along with his main climbing partners of the time – Richard Goldstone and Joe Bridges, and others of the largely New York City based ‘Vulgarians’ would work several nights a week at the West Side YMCA in Manhattan. Activities included pressing into handstands on the floor and on parallel bars, one arm chin ups, one arm lock offs and muscle ups on a gymnastics high bar, and slowly ascending and descending a 25-foot gym climbing rope. Goldstone, with whom McCarthy did the first free ascent of the famous ‘Co-Existence’, to the awe of all in the gym, would climb the rope starting from a sitting position on the floor with straight legs forward straddling the rope in an L position. He would then move up slowly doing alternating one arm pull-ups to the top, finally lowering himself ever so slowly, hand under hand, back down the rope. Doing front levers, back levers, muscle ups and attempting crosses on the rings were also part of the regular Vulgarian workouts. McCarthy, a trial lawyer by trade, was essentially a weekend and summer-vacations climber. Working out during the week in ways applicable to climbing fitness was important to him. Photo: Bridges

Matinee - Kevin Bein, justly called 'the Mayor' of the Shawangunks for his gregarious friendliness, pulling away at the hardest portion of McCarthy's 'Matinee' during the 1970s. (Bein is sensibly wearing a helmet at a time when it was not yet considered fashionable. Photo: Rich Goldstone.

Pink Laurel – Jim McCarthy and Joe Bridges on Pink Laurel, 5.9, in the Shawangunks..

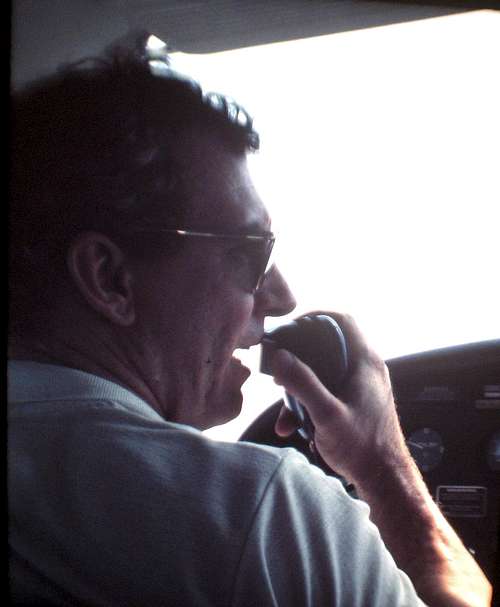

Jim McCarthy flying his airplane to a climbing area, June 17, 1972 - In the early 1970s McCarthy purchased a Cessna 180 airplane, having recently obtained a private pilot license. On weekends, he flew out of a small airport of Canaan Rd. in New Paltz. One summer day on a whim, Jim enticed his first wife, Diana Banks (the stage manager for the Joffrey Ballet Company; she occasionallygave informal ballet lessons to the climbers, including McCarthy, in an effort to improve their flexibility and grace of movement). McCarthy's mountaineering partner, Joe Bridges, and Jon Ross, long-time Gunks Guide and former owner of High Angle Adventures, to fly with him to North Conway, New Hampshire. Off they flew, rented a care, and drove to Whitehorse Ledge. After flying the whole way, while Diana took a sunbath, McCarthy led the other two climbers up the 'Slideing Board', a famous long and slippery 'slab' climbe with potential leader falls of a long distance. The threesome completed the climbe and were back in New Paltz for dinner that evening. (Driving time to North Conway from New Paltz, even today, is about six hours.) Photo: Joe Bridges.

A climber on the ankle breaking start to Drunkard's Delight. The 4 foot plus 5.6 roof on the second pitch is visible above.

Lee Hunsaker leading the 'easy' roof of Drunkard's Delight. Photo: Jason Halladay

A climber stemming through the difficulties of 'Fat Stick.' Photo: Andrew Bennett

Son of Bitchy Virgin - A climber high up into the dangerous portion of 'Son of Bitchy Virgin.' Photo Gottlieb Duwan

Baskerville Terrace – Brian Groves finishes the first and difficult section of McCarthy’s beautiful ‘Baskerville Terrace’ in the Near Trapps. (Another ‘easy’ looking climb with a greasy foothold that sent many climbers off in the wrong direction.)

Jim McCarthy on No Escape Buttress, Mt. Moran, Colorado. Photo: Yvon Chouinard

Snowpatch Spire in the Bugaboos – the ‘Kraus-McCarthy’ route ascends a line on the left skyline. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

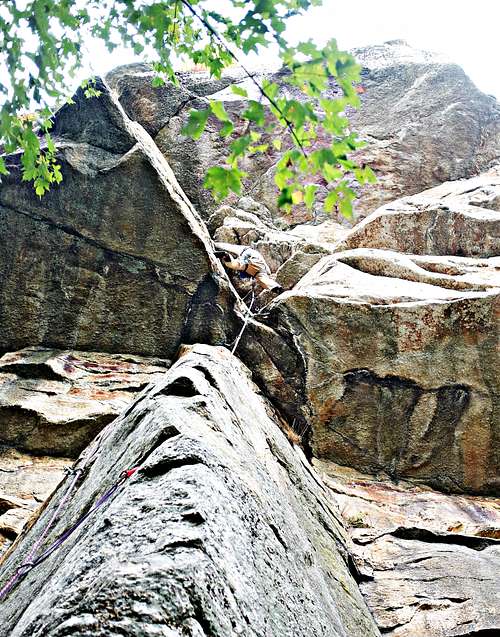

Snowpatch Spire – a climber begins the first difficulties while looking up into the ‘Kraus-McCarthy’ route of Snowpatch Spire. Photo:A Ike.

Cold at the Base of Mt Proboscis in the Rain

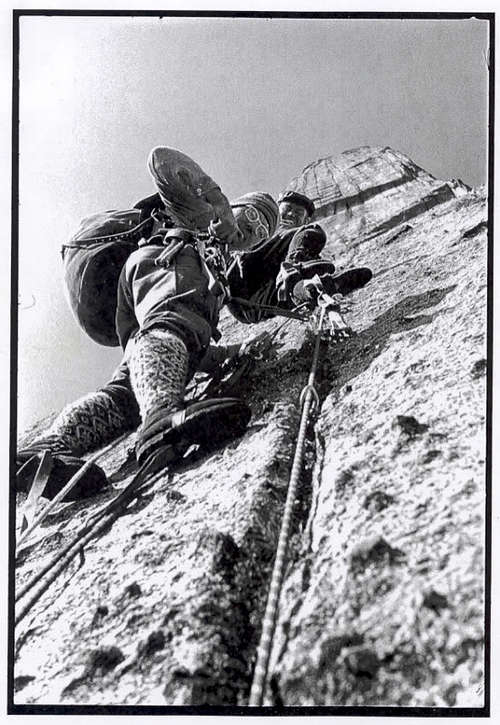

Royal Robbins leading on Mt Proboscis. Photo: McCraken

McCarthy’s team at the base of Mt. Johnson in the Alaska Range for an attempt on the East Buttress – McCarthy had been intrigued by a photo of Mt Johnson (on the Ruth Glacier in the Alaska Range) that his friend and climbing partner Galen Rowell had included in a slide show of the first ascent of the Southeast Face of Mt Dickey done by Rowell, Ed Ward and Dave Roberts in 1974. In this photo McCarthy (red top) and Tom Fisher prepare to ascent five rope lengths with mechanical devices to reach a high point attained the previous day both other team members Henry Barber and Joe Bridges. Photo Joe Bridges

McCarthy traversing the ninth rope length during the attempt on Mount Johnson, July 1975.

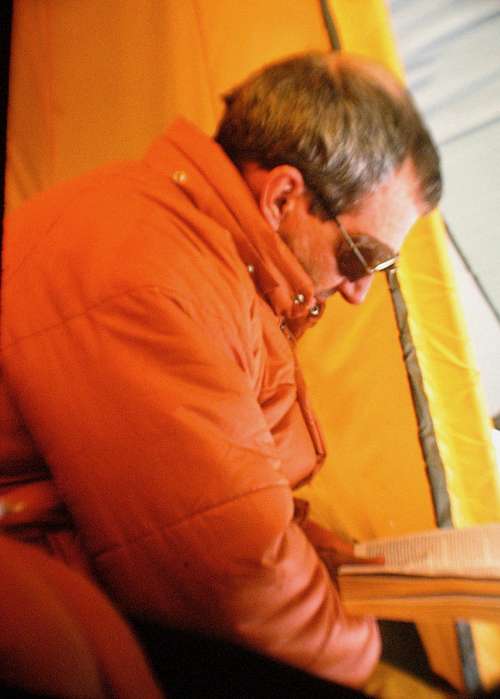

McCarthy reading the book ‘Alive’ about the survivors of an Andean plane crash while resting in the tent on the Ruth Glacier during the attempt on Mount Johnson, July, 1975.

McCarthy can read a book and drink a beer at the same time, Ruth Glacier, July 1975. Henry Barber had insisted that the team bring a case of beer for the trip. Barber had then skied down to base camp on the Ruth transporting the case on the front of his skis.

Double Crack - Climber Roger Benton has gotten just beyond the 'alcove' rest of the consistently overhanging 'Double Crack.' Climbs like these were first done on lead by those like McCarthy who took their fitness seriously. Photo Martha Busko

Roseland- A climber has finished the fearsome corner of 'Roseland' before the real difficulties begin.

McCarthy’s clowning suggests why many consider him the patrone of the Vulgarians. Possessing a pilot’s licence but no helicopter licence, he is preparing to be transported from Watson Lake to his summer hang out in the Cirque of the Unclimbables, Logan Mountains, July, 1973. Photo Joe Bridges

Jim McCarthy and Harthon Bill on the famed Lotus Flower Tower first ascent. Photo: Tom Frost

McCarthy Frost and Bill after finishing the Lotus Flower Tower

Snooky’s Return - A climber starts up the hard portion of 'Snooky's Return.' Photo Denis O'Connor

Ape Call - A climber surmounting the 'roof' of ‘Ape Call.’ A huge overhang with a giant hold, the leader is traditionally supposed to let both feet dangle while hollering like an ape. Photo Denis O'Connor

Westward Ha! – Climber Joe Bridges on McCarthy’s ‘Westward Ha!’, located on the high, steep and remote Millbrook crag at the Shawangunks. Photo: Richard Goldstone

Groovy – Laura Kosbar is trying not to get her fingers stuck in the sharp rock of McCarthy’s aptly named arching problem ‘Groovy.’ Photo: Richard Goldstone

Transcontinental Nailway – Climber Ivan Resucha holding tight and hammering in a replacement piton in the middle of the crux of 'Transcontinental Nailway.' Photo Rick Perch, 1971

Transcontinental Nailway – A teenager tests himself on McCarthy’s tricky but aesthetic ‘Transcontinental' 'Freeway’ in the late 1970s, with the name changed to me no more pitons and no more artificial techniques on this one. Photo John Ely, May 1977

Co-Existence - Darek Kuczynski fully focused on the crux of Co-Existence. Photo Denis O'Connor

9. References

Achey, Jeff, Chelton, Dudley, and Godfrey, Bob, Climb!: A History of Rock Climbing in Colorado, Mountaineers Books, 2002

Chouinard, Yvon, Climbing Ice, Sierra Club, 1978

Dumais, Richard, Shawangunk Rockclimbing, Chockstone, 1985

Gran, Art, A Climber’s Guide to the Shawangunks, American Alpine Club, 1964

Jones, Chris, Climbing in North America, Univ. of California Press, 1979

McCarthy, Jim, 'The South East Face of Mt Proboscis', American Alpine Journal, No 14, 1964

McCarthy, Jim, ‘West Face of Snowpatch’, AAJ, vol. 10, no. 2, 1957

McCarthy, Jim, 'The Jewell in the Lotus', Summit, vol. 15 (1969)

McCarthy, Jim, 'The Last Mountain Men and the Last Frontier', Summit, vol. 17, Dec 1971

Waterman, Laura and Guy, Yankee Rock nd Ice A History of Climbing in the Northeastern United States, Stackpole, 1993

Williams, Dick, The Climber’s Guide to the Shawangunks (The Trapps), Vulgarian Press, 1972/1996/2001

Williams, Dick, Shawangunk Rock Climbs (The Near Trapps and Millbrook, AAC/Vulgarian Press, 1972/1991

10 External Links

houin

houin