Note that this article has been significantly updated in 2021, incorporating detailed information from more sources.

1. SOURCES

![Unnamed Image]() Summit of Mont Blanc by Coppier - 1824

Summit of Mont Blanc by Coppier - 1824

Height: 4810 m Route: North side

First Ascent: Jacques Balmat (24 years old), Michel Paccard (29 years old) 8th August 1786

Main Sources:

- Dr Paccard’s narrative. An attempted Reconstitution, Ernest Hamilton Stevens - Alpine Club Journal (1929).

- Mont Blanc Premières ascensions 1770-1904, Jacques Perret and Michel Jullien Les éditions du Mont Blanc (2012) and

- Discours préliminaire aux voyages dans les Alpes (1789) et Voyages dans les Alpes, H.B. de Saussure - (1796).

- Travels in Switzerland, Alexandre Dumas (1834).

- Le Mont Blanc, Charles Durier, Hachette (1878).

- Guide to Chamonix and Mont Blanc, Edward Whymper - John Murray (1896).

- The Annals of Mont Blanc, Charles Edward Mathews (AC president) - T.F. Unwin (1898).

- Paccard contre Balmat, Henri Ferrand (La Montagne 1912, N°9).

- The Life of Horace Benedict de Saussure (1920) – Douglas William Freshfield (AC and RGS president) and Henri Montagnier.

- La controverse Paccard-Balmat, Heinrich Dübi articles dans Les Alpes - revue du CAS - (1930 et 1939).

- François Paccard and Bourrit Claire-Eliane Engel (Aj 57 - 1949) and Essai de reconstitution de la narration perdue du Dr Paccard (Alpinisme 1933 - traduction du récit de E.A. Stevens).

- The First Ascent of Mont Blanc, Graham Brown and Sir Gavin de Beer – Oxford University Press (1957).

- François Paccard and Bourrit Claire-Eliane Engel (Aj 57 - 1949) and Essai de reconstitution de la narration perdue du Dr Paccard (Alpinisme 1933 - traduction du récit de E.A. Stevens).

- L’invention du Mont Blanc, presented by Philippe Joutard. Archives Gallimard - Julliard (1986).

- 1786 Chamonix et conquête du Mont-Blanc – Thérèse Robache - Les Amis du Vieux Chamonix.

- Le Mont-Blanc dans la vie et l’œuvre d'Horace-Bénédict de Saussure Le Globe 1988 (Geographical review of Geneva) Paul Guichonnet - University of Geneva.

- Mont-Blanc 1786 -Journal du docteur Michel-Gabriel Paccard (Epigones 1992 - Catherine Guerin et Philippe Campione)

- Histoire générale du tourisme du XVIe au XXIe siècle, Marc Boyer - L’harmattan, 2005.

- The Summits of Modern Man, Peter H. Hansen - Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Alpine Journal, numerous numbers with key articles of Montagnier (AJ 1912), Stevens (1929/30/34/42/46), Gavin de Beer - Graham Brown (1949/57/58/62), H.Dübi (1930/42) etc...

8th August 1786, 5:45 pm, two figures are clearly seen at the Petits Rochers rouges, at 6:12 pm near the Petits Mulets and at 6:23 pm, on the summit of Mont Blanc.

Barons Adolph Traugott von Gersdorf and Carl Andreas von Meyer who had been following their ascent with their telescope from Chamonix, cannot believe their eyes:

THEY ARE ON THE SUMMIT!

Aside signing a certificate required the same day by Michel-Gabriel Paccard's father attesting of the ascent of his son with Jacques Balmat, von Gersdorf wrote the following more detailed document which proves the incredible fitness of the first ascensionists (Source Marcin Wawrzyńczak, translator of von Gersdorf's travel journals):

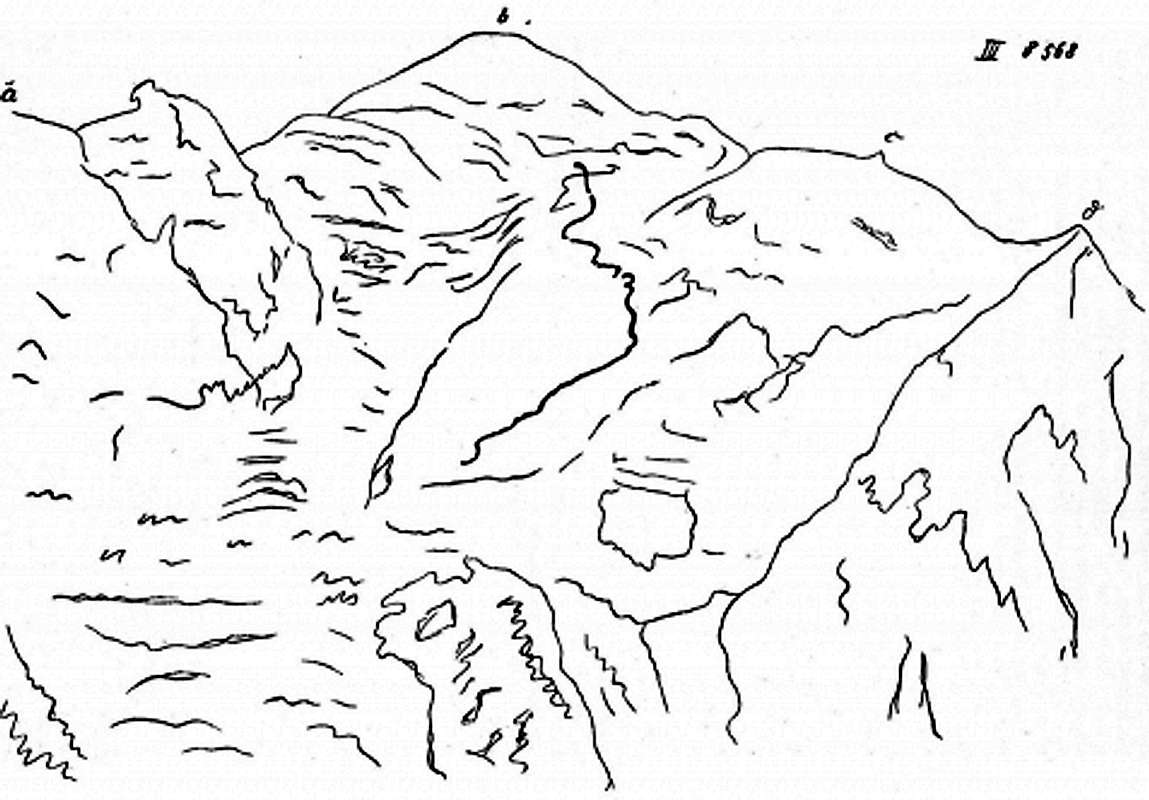

"... I heard that Dr. Paccard and Jacques Balmat would have left at noon yesterday, slept in a shelter on the top of the montagne de la Côte between the Glacier des Bossons and Taconnaz, and were seen climbing up several times today. After a long search, we saw them shortly after 5 pm on the straight line above the ridge of rock a [Les Rochers rouges supérieurs], where they passed swiftly on this horizon and, as they walked in the shade, they were clearly visible against the sun-lit mountain. They soon disappeared behind the uppermost rock band at b [The end of the Rochers rouges supérieurs and Les Petits Rochers rouges].

![Unnamed Image]()

“I went (with several companions) to Mr. Bourrit's chalet higher on the north side of the valley [Les Moussoux] where you see much better the summit of Mont Blanc than from the inn [Couteran]. The 2 climbers appeared after a while at rock c [Les Petits rochers rouges], which they must have reached through a hollow. They halted at the rocks several minutes and left at 5:45 pm. At 6:12 pm they were next to two very small rocks sticking out through the snow [Les petits Mulets]. They started again from there, always slightly to the left and reached the summit of Mont Blanc at 6:23 pm. One was always about 100 paces ahead [about 30m]. They often stopped for a moment.

![Unnamed Image]()

When arriving on the summit, they disappeared at once behind it, but soon reappeared after about 1 minute. They were visible then for a long moment and then left the summit swiftly, at 6:57 pm. They ran down and 6 minutes after they reached the rock c [LesPetits Mulets], as the dotted line of the sketch shows, from there I could not see them any further. I suspect that they had chosen to camp for the night so that they could go up again early the next morning. - The father of Dr. Paccard, notary of the Chamouni valley, came to us to get a certificate from us stating that we had seen his son on the summit of Mont blanc, but he delayed his request to the following day, in order to await his son's return, as we had decided to stay one more day."

11 minutes from the Petits Mulets to the summit, a distance of 120 m, so a speed near to 600 m/h, with their loads, a performance that even Kilian Jornet would have envied! And this corresponds well with the affidavit signed by Jacques Balmat at the request of Michel Paccard:

"... M. le docteur continued to climb with ease: we reached a small rock [Les Petits Mulets], behind which I sheltered myself from the wind, while M. Paccard examined it and took stones. We were near the summit; I went left to avoid a snow slope which M. Paccard climbed straight up with courage to get directly to the summit of Mont Blanc. The bend which I followed made me a bit late and I had to run to be nearly at the same time than him on the summit..."

And less than 5 hours later they were down to their shelter at the Montagne de la Côte!

THE FIRST ASCENT of THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN of THE CONTINENT and RUNNING UP IT. WHAT A FEAT!

2. THE DISCOVERY

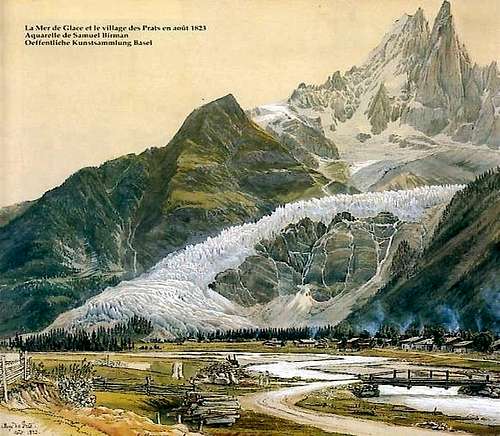

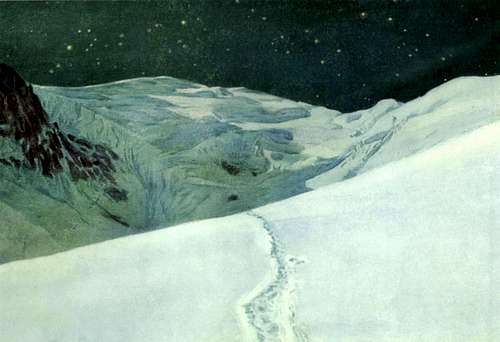

![Unnamed Image]() Mer de glace 1823

Mer de glace 1823Up until the middle of the 18th century, the MONT BLANC was totally unknown.

The Swiss scientists had explored their own mountains but had avoided the Chamonix valley (then part of the Savoy duchy and realm of Piedmont-Sardinia). Its mountains were named the “cursed mountains”.

In 1741 Windham and Pococke climbed to the Montenvers and went down to the Mer de Glace, then easily accessible as more than 130 m higher than now. They made the valley range known in the whole of Europe with their expedition’s tale published in 1744 and in French. They had come with armed servants as if they had been on an expedition to the centre of Africa to find quite civilized villagers led by a benevolent prior.

The following year, the Swiss engineer and cartographer, Pierre Martel, followed their tracks and was the first to name properly a number of summits of which the MONT BLANC which appears for the first time in a letter he sent to Windham. He calculated the altitudes of the summits and established that the MONT BLANC was the highest of all with an altitude of 4495 m, an error of 315 m.

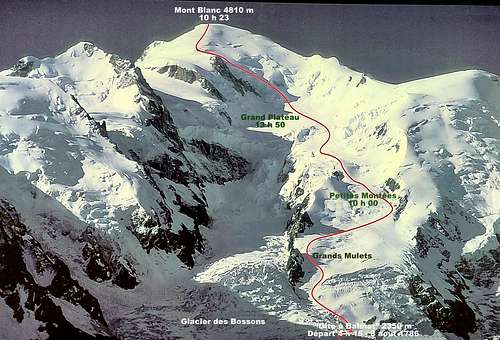

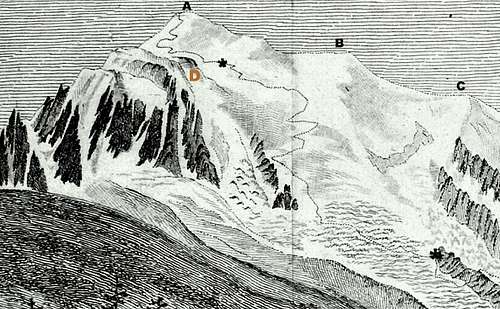

![Unnamed Image]() G: Grand Plateau - P: Petit Plateau - E: Upper Ancien Passage - Yellow line above G: the Lower Ancien Passage - D: 8th June 1786 guides' attempt to Dôme du Gouter - F: Corridor route 1827

G: Grand Plateau - P: Petit Plateau - E: Upper Ancien Passage - Yellow line above G: the Lower Ancien Passage - D: 8th June 1786 guides' attempt to Dôme du Gouter - F: Corridor route 18273. THE PROTAGONISTS - HORACE-BENEDICT de SAUSSURE's REWARD

![Unnamed Image]() Horace Bénédict de Saussure

Horace Bénédict de Saussure 3.1. Horace Benedict de SAUSSURE

the famous Swiss scientist from Geneva, visited Chamonix in the summer of 1760, while only 20.

As a scientist and researcher, while studying physics, chemistry, and natural sciences, very early he is convinced that "the study of mountains can accelerate the theory of the Globe. Plains are uniform... while the high mountains infinitely varied in their matter and forms present in the open natural cuts of a very vast spread where one observes with the greatest clarity, where one embraces at a glance the order, the situation, the thickness and even the nature of the basis they are made of..."

Bénédict de Saussure is the first to concentrate all his science very varied knowledges on one specific domain: the mountains and for him the mother of all the mountains of his continent is the Mont Blanc.

Twenty years after the first ascent of Mont Blanc, in 1786, he will write: "Since I was born I had the most determined passion for mountains... aged 18, in 1758, I had crossed several times the mountains nearest to Geneva. Since 1760, I have not spent one year without doing great ascents, and expeditions to survey mountains. In this span of time, I crossed 14 times the entire Alps using 8 different routes; I did 16 other trips in the centre of this chain; I crossed the Jura, the Vosges, the Swiss mountains, part of Germany, mountains of England, Italy, Sicilia and neigbhouring islands; I visited the volcanoes in Auvergne, part of the Vivarais and several mountains in the Forez, the Dauphiné and Burgundy. I did all those journeys with a miner hammer in my hand with no other aim than to study the 'natural history', climbing all feasible summits which allowed me some interesting observation and always taking back with me mining samples, particularly from mountains which provided an interest for the theory, to study them at length."

Before getting back to Geneva he had a notice published in the three valley parishes (Les Houches, Chamonix and Les Pélerins) stating that he would offer a large sum of money to those who would find a route up to the top of Mont Blanc.

During the following 15 years, his promised reward received no attention from the locals. There were no visitors, and they did not see it as a good enough reason to stop their field tasks during the sunniest part of the year.

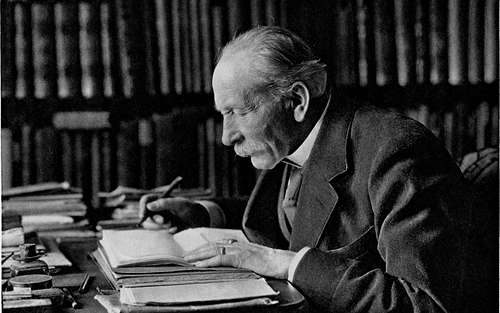

![Unnamed Image]() Marc Théodore Bourrit

Marc Théodore Bourrit3.2. Marc Théodore BOURRIT (1739-1819)

Precentor of Geneva's cathedral. Painter, engraver and known writer of travel books in the Alps which he illustrated with his paintings, he was well seen by the kings of Savoy-Piedmont-Sardinia and France who gave him a pension. Although considered with de Saussure as a pioneer of the exploration of the Alps, he is no scientist and came from a French family who took refuge in Geneva during the chase against protestants in France. His ambition to be the first on top of Mont Blanc and write the first account of it will made him become voluntarily the 'Villain' who will trigger the controversy by disparaging unduly Paccard in favour of Balmat and above all of himself. A "swollen waterskin" (minister Wyttenbach from Bern), he is conceited, a braggart, suffering from an inferiority complex, jealous to a point of not hesitating to use the most perfidious means when his reputation is at stake, Bourrit never ceased to pour out his poisoned slime onto his rival... draping himself with the title of 'historian of the Alps' (L. Seylaz in AJ 62 1957). As Claire Eliane Engel wrote: "his physical capabilities did not match his ambition… a man who walked badly and spoke too much’ but the 1rst to publish its ascent." He saw himself as a competitor to Paccard and de Saussure and dreamed to be the 1rst on top of Mont Blanc which he will never be able to climb. And he was a very active and clever adept of Francis Bacon's quote: "Slander boldly, something always sticks".

As visitors started to come and were paying to be guided to go to the ‘Glacières’ (the Mer de Glace and up to the Glacier de Talèfre), the locals then understood that if Mont Blanc were climbed it would result in a welcome income for them, SO ATTEMPTS STARTED IN 1775.

The two men who after ten years of unsuccessful attempts by many at last reached the top were both from Chamonix:

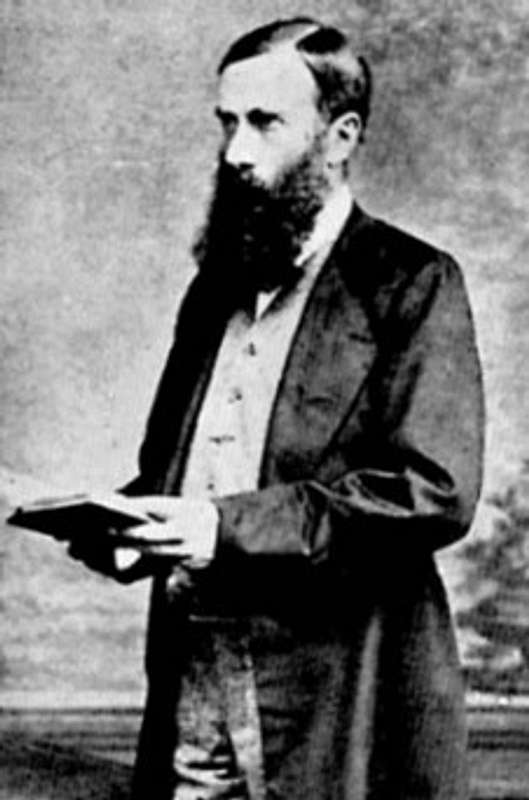

![Paccard - Medalion portrait]() Paccard - Medalion portrait

Paccard - Medalion portrait3.3. MICHEL GABRIEL PACCARD

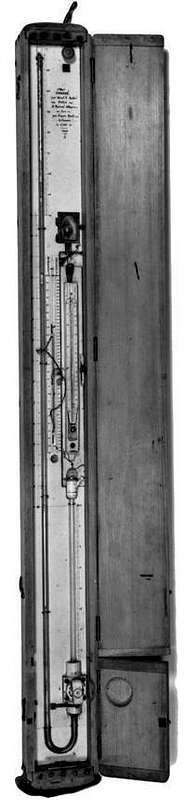

The Chamonix doctor and amateur scientist. Born in Chamonix in 1757, his father was the town’s solicitor. He passed his medical exams at Torino, capital city of the Savoy duchy, established himself as a doctor in Chamonix and will act in his later years as its Justice of the peace. For Paccard, climbing Mont Blanc and making experiments on its top, measuring its height would bring him a worldwide scientific fame… alike de Saussure, already famous for his scientific works (de Saussure, one of the last all-around 18th century scientists, is one of the founders of modern geology, and meteorology). One must note that Paccard was in close contact with de Saussure several years before his successful ascent, sending him measurement results, geology and botanist findings he was gathering on his attempts. The barometer he used on top of Mont Blanc was procured to him by de Saussure from England. The barometer he used on top of Mont Blanc was procured to him by de Saussure from England.

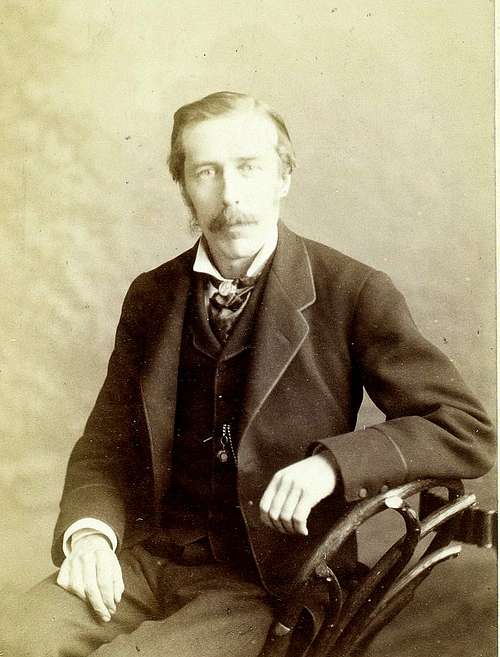

3.4. JACQUES BALMAT

![Balmat medalion portrait]() Balmat medalion portrait

Balmat medalion portraitThe poor peasant and crystals' hunter. Born in Les Pélerins (a village 1,5 miles from Chamonix) in 1762, he was a modest peasant working on his father's meadow and a crystals's hunter to improve his meager revenue. For him, finding the way up to the top meant receiving de Saussure's reward which would enrich him and the aim to become a guide for the rich visitors to come. Both were highly adventurous men like all the others who participated in the many attempts on the highest summit of their 'cursed' mountains. This also must be said of the illustrious scientist, Horace Benedict de Saussure who initiated it all and spent most of his life in the mountains making experiments often in highly risky conditions.

The association of those two men should have worked perfectly. Their motivations were different, and they were not competitors. Paccard was paying Balmat for his task as a porter of his scientific instruments and was letting him have the entire award promised by de Saussure.

So, what went wrong and why for two more centuries and still now

THE TRUE TALE IS SO HARD TO GET?

4.1. BOURRIT and THE SEEDS OF DISCORD

All started well with an article published in "Le Journal polytype des Sciences et des Arts" on 18 Septembre 1786 in Paris: "...Nul voyageur n'avoit encore réussi à parvenir au sommet du Mont Blanc : ce succès doit être réservé à M. Paccard, jeune médecin, originaire de Chamonix, qui a étudié à Paris. Il coucha à la vallée de glace ; suivi du dénommé Balma, il partit le lendemain à quatre heures du matin, et il arriva, après 14 heures de marche, au sommet de la montagne. Des curieux qui les suivoient des yeux, armés d'un téléscope, les aperçurent sur la sommité la plus élevée. Nos intrépides voyageurs y restèrent 32 minutes et redescendirent dans quatre heures, au clair de la lune... " (No traveller had managed to get to the top of Mont blanc: this success must be reserved to M. Paccard, young physician, from Chamonix who has studied in Paris. He slept in the ice valley and followed by the the man Balma he started the following day at 4 am, and, after 14 hours, reached the summit of the mountain. People who followed their progress with a telescope saw them on the highest point. Our dauntless travellers stayed 32 minutes and came down in 4 hours in the moonlight...)

Clear conclusion: Paccard was the organiser and the leader of this expedition. But this review had a limited number of readers and had no impact, even if it preceded the first pamphlet of Bourrit "Sur le premier voyage au sommet du Mont Blanc" which disparaged Paccard to the benefit of Balmat and the author himself in keeping away a competitor to his "guides to the Alps"..

Thus, Bourrit created the controversy:

Bourrit had seen Balmat when he came to Geneva, anxious to get his reward from de Saussure and fearing that he would not give it to a simple "worker". So, he lied stating that he had found the route and arrived first on the summit. Bourrit embellished further his tale and published it as a pamphlet in the Mercure de France (October 28th, 1786). In it, he gives all the merit to Balmat and disparages Paccard:

- Balmat would have thought out the route,

- led all the way to the top,

- reached it first,

- went down to help the 'poor doctor' who was so exhausted that without him he would never have reached the summit,

- Bourrit went so far as insinuating that Paccard never reached the summit and had not paid Balmat.

Paccard replicated in publishing a rectifying account in the Journal de Lausanne (February 24th, 1787), to which Bourrit replied (March 3rd, 1787), repeating his version and accusing Paccard of being jealous of the glory attributed to Balmat (by himself!). This came to de Saussure’s notice. By then he had the tale from Paccard himself and the testimonials of Baron von Gersdorf and Carl Andreas von Meyer. De Saussure wrote to Bourrit asking him to correct his statement. His letter pushed Bourrit to publish a postscript modifying his tale and restoring some of the truth, but not all. Then Paccard published in the Journal de Lausanne (May 12th, 1787) two certificates signed by Balmat (October 18th, 1786 - see appendix 1), one with the proper story, and the second specifying that he had been paid by Paccard. This stopped the controversy for a while as Bourrit could not openly contradict Balmat's own testimonials rejecting all of the false story he had put up. To show how villainous Bourrit could be, when François Paccard (Michel-Gabriel's cousin and a de Saussure's chief guide quite active in the attempts) got infuriated after reading Bourrit's publication "slandering his young cousin" as wrote Sir Gavin de Beer who added: "he probably called Bourrit a liar or something worse", Bourrit who was in Chamonix, frightened*, appealed to the Savoy police and had him sentenced to 3 days imprisonment in Bonneville.

* The famous French highwayman Mandrin escaped from the French troops by getting into the Savoy duchy, guided by François Paccard, then 20, who was exiled from Savoy for this action and later pardonned. So he had a reputation of a daredevil, not astonishing that Bourrit got frightened! (From Claire Eliane Engel AJ 57 "François Paccard and Bourrit").

Again in 1792, Bourrit had a quarrel with von Gersdorf and Balmat because he had been delaying handing over to Balmat the sums collected by von Gersdorf in Germany to his benefit. This is probably why once again he changed his story in his book Descriptions des Cols ou Passages des Alpes (1803) in which he states:

‘ it is nevertheless true that Dr. Paccard rightly shared the glory of this Chamoniard, if indeed he was not, as we have reasons to believe, the prime cause of it’.

THE TRUTH AT LAST THOUGH NOT COMPLETE!

And that was going to be totally washed away by Alexandre Dumas’s tale published in 1834 replicated by all Balmat’s worshipers still nowadays.

Paccard nor Balmat did publish a written tale of their ascent. However, Paccard had announced the publication of a book which would “give the history of the attempts to ascend this mountain etc…” This can be read on the few copies of the remaining book subscriptions which Paccard had printed and sent out.

![Unnamed Image]() Michel Paccard portrait by Bourrit

Michel Paccard portrait by Bourrit

But the book was never published, and it was due to Bourrit’s manoeuvres, who saw Paccard as a potential rival in alpine literature. Paccard had the bad idea to ask Bourrit’s brother in-law to publish his book. A Geneva editor, leader of the political party of the "Natifs" they both belonged to - This party was quite active in asking for more rights in this pre French revolution period and during it - he delayed its publication until Bourrit and de Saussure accounts were published. By then Paccard almost certainly decided not to publish it because his scientific observations were insufficient compared to de Saussure: his barometer' measures on top of Mont-Blanc had important errors. A scientist and prominent citizen in Chamonix, Paccard is just an enlightened amateur scientist in the outside world. A year after him and Balmat, de Saussure makes the ascent of Mont Blanc: he is 47 years old and already famous as a scientist in the whole of Europe. He organized a caravan with 18 guides, asking Balmat to lead it.

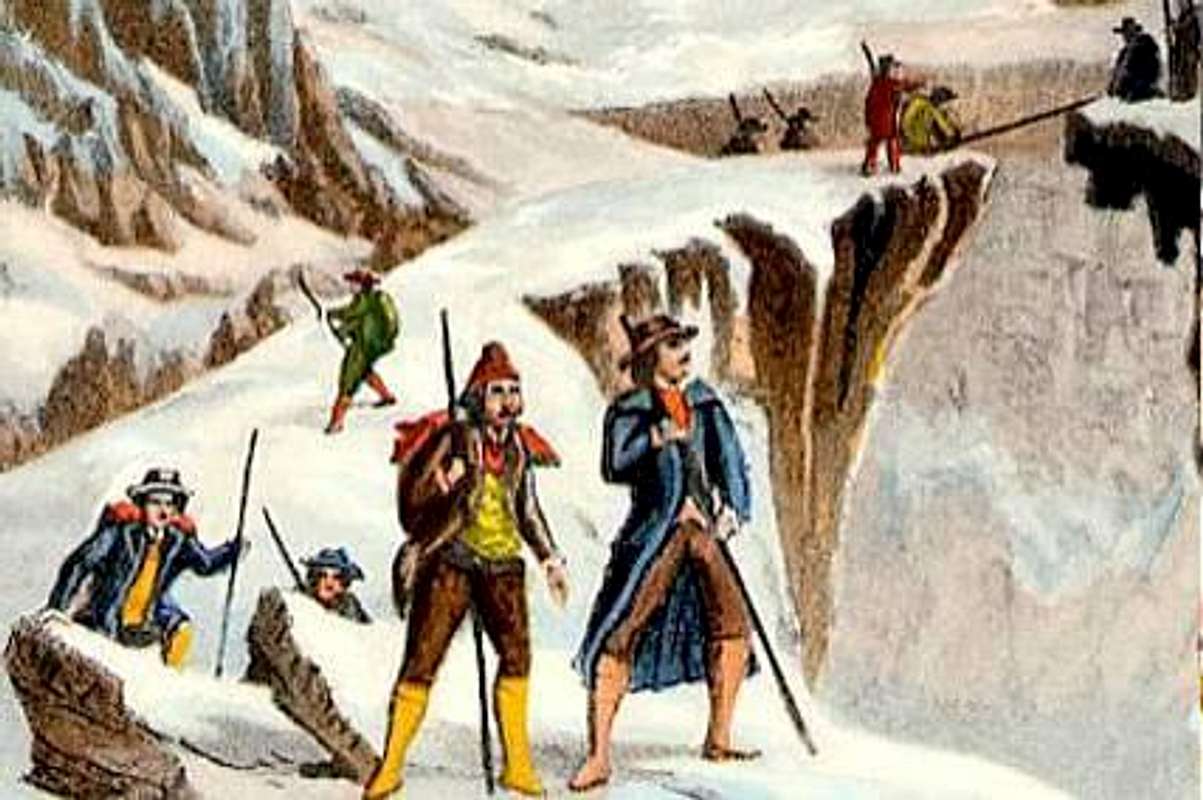

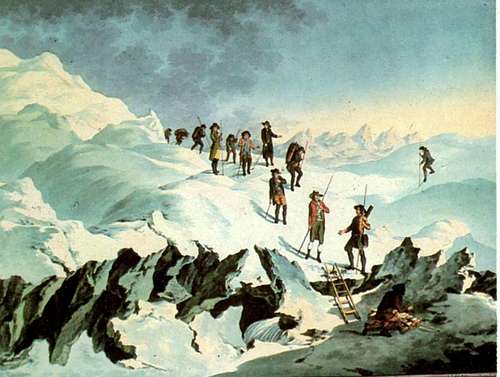

Balmat with Alexis Tournier and Jean-Michel Cachat ‘the Giant’ had done the second ascent on 5th July 1787 to prepare the grounds. With de Saussure and his personal servant, they were 20 in all. The guides carried the equipment, food, numerous scientific instruments, a ladder, a mattress, blankets, sheets, pillows, crape masks to prevent being snow-blinded as Paccard had been and a tent; they had ropes (but limited to 5 to 6 m, the guides using them only to get their clients over a crevasse or out of a difficult spot and not to secure their crossing of the glaciers and snow slopes – climbing techniques did not exist at all then). They also had crampons, long batons iron-pointed and axes and to secure his ascent, de Saussure had two huts previously built on the Montagne de la Côte and the Grands Mulets, although in the end he used the tent twice during his ascent which took 4 days including the descent.

De Saussure’s ascent will outshine Paccard and Balmat’s first ascent in the whole of Europe with its account, sketches, engravings and the many more measurements and experiments done on the summit than Paccard’s. He stayed on it 4 hours and a half against the 35’ of Paccard, measured the height of Mont Blanc more accurately: 4845 m - 35 m above the real height which finally he reduced to 4775 m, taking into account a mean average of other scientists' trigonometrical measurements. Paccard's estimate was 5218 m; suspecting a fault in his barometer after new measures taken on the Montagne de la Côte, he corrected it to 4738 m. Not that far out and de Saussure will complete his experiments in July 1788 during an extraordinary 17 days stay on the Col du Géant. (His guides were so frightened that he would stay much longer that they did hide the remaining food to force him to go down).

The tale written by the illustrious geologist (Relation abrégée d’un voyage à la cime du Mont Blanc September 1787, one month after his ascent) had an immense impact throughout Europe. It was the last stroke marginalizing the poor Paccard who finally gave up his publication considering the superiority of the scientific results brought by de Saussure.

Six days after de Saussure, the 4th ascent was made by the young Mark Beaufoy, future colonel and fellow of the Royal Society, with 10 guides led by Jean-Michel Cachat (nicknamed the fearless Giant) who measured the latitude of Mont Blanc. On the 5th ascent the following year achieved by another Englishman (William Woodley) - this time his motivation was more personal than scientific - with a party of 22 guides led again by Jean-Michel Cachat, the usage of the rope was better understood and used to protect parties over a glacier. The trade of guiding had really started and will not cease to thrive since.

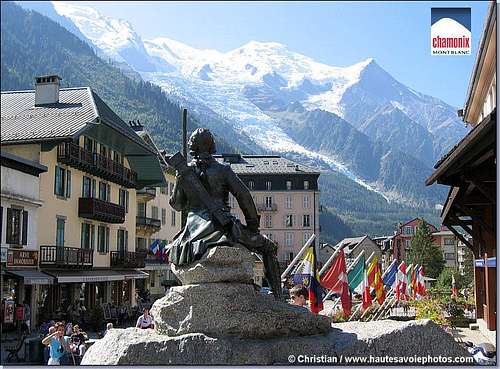

![Balmat showing Mont Blanc to de Saussure]() Balmat showing Mont Blanc to de Saussure

Balmat showing Mont Blanc to de Saussure4.2. ALEXANDRE DUMAS COMES IN

We know for some time now that this tale is completely made up. There are several written proofs : the certificate that Paccard had Balmat signed with two witnesses; also testimonials and writings: baron von Gersdorf and his friend baron Carl Andreas von Meyer who ascertained that it is Paccard who found out the route and that the two men reached the top together; de Saussure’s own accounts, Paccard’s diaries etc…

Even if Balmat has embellished his role to get the promised award, Bourrit could not ignore the truth. So, it is voluntarily that he excessively gave credit to Balmat and disparaged the doctor.

Why? Jealousy without much doubt; he also wrote that he had been shocked by the doctor’s subscription bulletin which did not mention Balmat: Bourrit the valiant robin? Or was he flattering Balmat in order that he would guide him to the top before de Saussure as he wrote in a letter to Balmat?

Despite Paccard’s denials, the production of the affidavit he had Balmat signed re-establishing the truth (see appendix 1), despite de Saussure reluctance after he got the tale from Paccard and his criticisms of Bourrit for his lack of objectivity, this distorted story found with ALEXANDRE DUMAS a fantastic amplifier to the point that it is still today repeated again and again by badly informed authors or discarded as they prefer the legend to the truth. In 1832, during his trip to the Alps, Dumas then 31 years old, a recently successful playwright, asked Balmat to dine with him. After much food and wine (3 full bottles for Balmat, then 70 years old), the old guide gave his version of the 1rst ascent of Mont Blanc (Paccard had died five years before) and it is this tale – further embellished – that Dumas gives in his Impressions de Voyage en Suisse, an astounding success which will contribute to comfort Balmat’s legend at the expense of Paccard who was not anymore there to defend himself.

For more than a century, Paccard will not even be mentioned when the 1rst ascent of Mont Blanc is evoked.

![Paccard statute Chamonix erected in 1986, a century after that of Balmat and de Sausssure!]() Paccard statute Chamonix erected in 1986, a century after that of Balmat and de Sausssure!

Paccard statute Chamonix erected in 1986, a century after that of Balmat and de Sausssure!

It is worth noting that the statute erected in 1887 of de Saussure with Balmat showing him the Mont Blanc's route for the centenary of his ascent of Mont Blanc was due to a initial donation made by Joseph-Agricola Chenal from Sallanches - MP in the Sardinian governement - in recognition of de Saussure role in making famous the Mont Blanc with the mentions: “À H.B. de Saussure Chamonix reconnaissant” and on the back the list of the additional contributors: the French, Swiss, Italian, and British alpine clubs, as well as the Appalachian mountain club of Boston, the Austrian tourists society and the Academy of Sciences of Paris. In1875 a granite stela with a medallion of Balmat was set on the Chamonix church square.

Paccard had to wait until 1932 (28th of August), when a medallion of him was placed at the entrance of the town hall, at the initiative of two American Alpine Club members, the doctors William Sargent and James Monroe Thorignton who covered two-third of the cost, the participation of the Alpine Club, the CAF, the CAS, the CAI, and H.F. Montagnier, who donated the stela to the town of Chamonix. At the same time the Mayor and Council of Chamonix gave the name of Dr. Paccard to one Chamonix main streets. All Alpine Clubs presidents were present as well as three of the men whose research allowed to restore Dr. Paccard's proper role: H.F. Montagnier, Thomas Graham Brown and the Swiss Heinrich Dübi.

Charles Durier, president of the Club Alpin Français, historian and geographer, friend of Joseph Vallot, reproduced Dumas’s story in Le Mont Blanc - 1878, reinforcing it by giving full credit to Bourrit's lies, discarding de Saussure testimonials and writings concerning Paccard, and since, many French people, including in Chamonix and within French guides syndicates, will believe that alleged tale. Jacques Balmat is their hero and as it was so stated in one of the French Guides website giving the ‘Balmat’s view of having found the route, chosen Paccard to accompany him to attest his success - as being the doctor of the village his word would be trusted -, Paccard progressing on all four, demoralized, being placed by Balmat in a site protected by the wind while Balmat goes to the summit alone’, thus replicating Dumas’s tale and they do not even mention that Paccard also reached the top.

They end up their heroic tale of Balmat in stating:

"Such is the statute of the hero. Until today, it has stayed solidly bolted in the model we reproduced, despite all the documents that have appeared, and the blows stricken against it. There is little chance that the Paccard’s advocates will ever manage to knock it down. One does not modify the physiognomy or the history of legendary heroes." (extracted from Montagnes, Marcel Rouff 1931, Gallimard)

Rejecting the evidence, those people prefer the myth. For them the association of de Saussure, the rich educated foreigner and Balmat, the Chamonix guide and crystal hunter is a far greater symbol than the association of Paccard and Balmat, two young adventurous men from Chamonix making the 1rst ascent at par.

Paccard does not fit in the picture as they want it to be: being an amateur scientist and a local he cannot be assimilated to a guide, unlike de Saussure and the British from Cambridge and Oxford who will be the first alpinists, and clients of the Chamonix guides. They forget how closely acquainted both Paccard and Balmat families were: Paccard married Balmat’s sister (10 years after their ascent) and his great grandson was Adolphe Balmat, a Chamonix guide! Furthermore, Paccard had two cousins, François and Michel Paccard who were part of several of the early attempts. His own ability in the mountains was as good as any of the locals and Jacques Balmat, but his main weaknesses seem that he was a doctor and not a guide, a local and not a rich visitor, an amateur scientist and not a client!

![Balmat Mont-Blanc]() Balmat Mont-Blanc by Bacler d'Albe

Balmat Mont-Blanc by Bacler d'Albe

Among the French authors who recently re-established the true story, Philippe Joutard, a university professor and historian wrote in ‘L’invention du Mont Blanc’, published in 1986 for the centenary of the ascent:

"Paccard was ‘unwanted’. The pair Balmat-Saussure appeared then as the model of the rope party, linking the Chamonix guide to his foreign client”.

And he adds: “In the second part of the 20th century with the weakening of that model, the outcast will get back to the place he deserved, in the literal sense: The Grand Larousse ignored totally Paccard – as if Balmat had climbed Mont Blanc alone. It is only in the 1960 edition that the doctor will be entitled to a little note…”

Even today, many French authors and mountain guides although accepting the role of Paccard still write that Balmat is the one who discovered the route, which is a myth created by Balmat and reproduced by Alexandre Dumas. The best is to quote H. Dübi who reacted at the publication of the Rochat-Cenise's book Jacques Balmat du Mont-Blanc (published in 1929 re-edited since) on this specific myth:

11° M. Rochat, basing himself on Balmat and Alexandre Dumas, writes that Balmat, at the end of June 1786, went to the Brévent to look for a route to Mont Blanc using a telescope. This assertion from Balmat appears in the Alexander Dumas's interview, so after doctor Paccard's death. It is in fact Paccard, who from 1783, did go several times to the Brévent to study the mountain with a telescope and find the route which he will follow later with Jacques Balmat. "Marie Couttet who had examined from the Dôme du Goûter the slopes going from the Grand Plateau on the left, judged them as offering no hope. However it seemed to me that one could climb them by a large snow cornice whill goes up steeply towards the left" (Dr Paccard's reporting to H.B. de Saussure). Here is how the route was found and the doctor speaks even of the Corridor's route in case of avalanches. The fact is attested by Paccard himself in an article he sent to the Journal de Savoie published the 16th of septembre1825...

12° As far as the 8th and 30th June expeditions are concerned... it is pure invention... First there has been only one expedition, that of the 8th and 9th. From doctor Paccard' s diary based on the guides' reports, from de Saussure, Bourrit and Coxe' writings result the following:

Jacques Balmat on his own initiative decided to join an expedition which on an order from de Saussure was to pursue the reconnaissance in the direction of the Dôme du Goûter. Two parties were due to meet on the Dôme, one coming from the Montagne de la Côte, while the other was coming by the Col de Voza and the Aiguille du Goûter... When both met at the Dôme, they pushed to a point where today is the cabane Vallot. They did not fing the cairn left by Cuidet and Couttet on September 17th 1784. Facing the apparent difficulty of the Bosses ridge, they gave up and went down by the snow valley, but JB, and reached Chamonix the same evening. Jacques Balmat who did not make himself much noticed during the day, stayed behind, probably in search of crystals. He did not succeed to join his comrades and had to spend the night on the glacier above a crevasse which the others had jumped over. He went home the following day without any damage from his unintended bivouac. Therefore his feats were limited to an extended walk and a happy return, alone, following the tracks of his predecessors and a known route. All the rest of Rochat's tale: the stampede over the Bosses ridge, the climb to the North-East shoulder of Mont Blanc, the so-called exploration by him alone of the route from the montagne de la Côte up to the Petit Plateau crossing the Grands Mulets is a fairy tale." (H Dübi Les Alpes 1930). See also 5.8. The Guides Attempt by the Dôme du Goûter (1786) by Paccard.

At the time of the ascent, Balmat was no guide (they did exist but their role was limited to taking visitors onto the Mer de Glace and up to the Glacier de Talèfre – giving access to les Droites and les Courtes, a favourite place for the crystals hunters - but not yet to climb summits), but a young peasant still working on his father’s land and his sole ambition was the lure of a considerable sum of money promised by de Saussure and making himself a name as a guide which would extract him and his wife from poverty. This is what made him go to the top of Mont Blanc.

![Bénédict de Saussure Mont Blanc ascent (H. Lévèque 1790)]() Bénédict de Saussure Mont Blanc ascent (H. Lévèque 1790)

Bénédict de Saussure Mont Blanc ascent (H. Lévèque 1790) However no sum of money would have been enough if it had not been for his appeal for adventure and risk taking and this goes as well for all the others who attempted the first ascent of Mont Blanc. And there is nothing wrong with Balmat’s main motivation: it should be easier to understand him if one can just for a moment try to imagine how tough were the lives of those men living in a remote valley encased between the highest mountains of Europe. If he finally joined Dr. Paccard it was because the latter claimed nothing for his share, letting Balmat get de Saussure's full reward, paying him for his service as a porter and giving him the money that baron de Gersdorf asked Paccard to give him. This was an advance to a much larger sum of 16 Louis d'or that the baron collected for him in Germany which he then asked Bourrit to give to Balmat. It is worth noting that Bourrit only gave 10 Louis d'or to Balmat pretending that the rest was to be used to cover the costs of a brochure at the glory of Balmat! The latter asked a lawyer, M. Wallner, to get the 6 Louis d'or unduly taken by Bourrit as he never asked for such a brochure to be published and as for sole reward Bourrit had asked to be guided by him to the top of Mont-Blanc. Whatever the meanness of Balmat and Bourrit, Paccard as the explorer eager to make discoveries, striving for glory depicted by Durier and so many French authors since is purely a myth.

Paccard's ambition was to obtain recognition as a scientist in the path of de Saussure. Alpinism did not exist then, and the only interest to climb Mont Blanc was purely scientific. The choice of Mont Blanc by de Saussure came from the fact that he believed that mountains reveal far more the structure of the earth, the atmosphere and ‘the great processes of world-building’ and not a love of landscape or an urge for adventure. All the Chamoniards (and those from St Gervais) who attempted to climb Mont Blanc, aside Paccard the scientist and most educated Chamoniard of the lot, were like Balmat and it is the de Saussure’s award and fame that they were after for the same reasons. In reading the story of the 1rst ascent of Mont Blanc, to really comprehend what occurred, the personalities involved, their motivations and indeed their great courage and physical strength, but also their conflicting interests, one must try to bear in mind the economics, the social situation, and ways of thinking of the time and the mentality of the people involved. Reading it with the eyes of today can only lead to misunderstandings.

4.3. AC MEMBERS and HEINRICH DÜBI - AN EXTRAORDINARY CHAIN TO RESTORE THE TRUTH

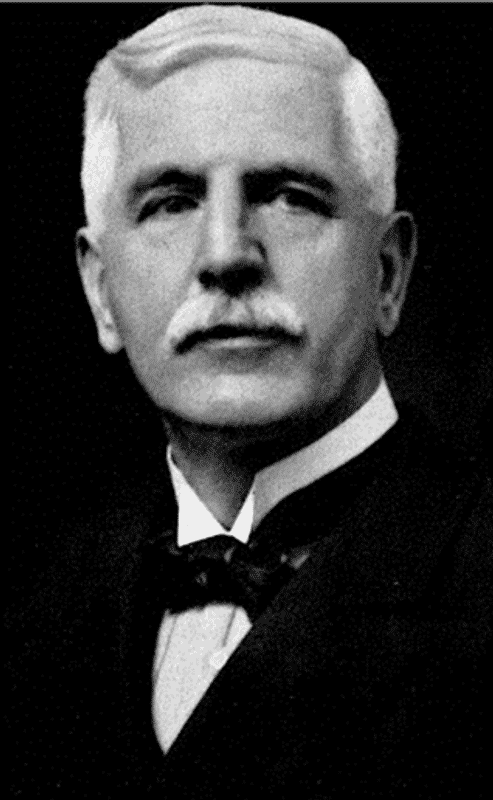

During nearly a century, mountaineers, members of the Alpine Club, created an extraordinary chain in search of the truth and the re-establishment of the right role of Paccard. It started with Whymper (then in his fifties). In preparation of his "Guide to Chamonix and the range of Mont Blanc" (1896) he met Henri de Saussure, grandson of the great scientist who in 1879 - who did provide him key information he had about Paccard, Bourrit and Paccard's correspondance published in the Journal de Lausanne including the Paccard's affidavit signed by Balmat. '[Henri de Saussure] ‘made in Geneva a highly documented lecture defending the fame of Paccard against the allegations of a legend which threatened to become a classic… he had found among his grand-father papers, letters and notices which proved that doctor Paccard was a friendly character, an alpinist of much merit and a man able to understand science’s mission and to pursue it selflessly.” (H Dübi Les Alpes 1939). Whymper wrote a letter sent to all inhabitants of the Chamonix valley asking for Paccard's lost narrative of the ascent which received no response, so Whymper based himself on Alexandre Dumas's interview of Balmat, the only full written story available. He added the affidavit that Balmat had signed, noting to his great surprise and disbelief that it contradicted totally the story he told Dumas, adding that for a century the name of Michel-Gabriel Paccard had gone in total oblivion and ended with the question: "But who is this Dr Paccard?" (p.30). Other members of the AC took up the torch:

The first major publication came from Charles Edward Mathews (1834 – 1905), a president of the Alpine Club, co-founder and first president of the Climber's club, with the Annals of Mont Blanc published in 1898. Matthews had obtained Dr Paccard’s diary from his great-grand son, Ambroise Adolphe Balmat, which he used in his book and bequeathed it to the Alpine Club. He will be followed by the Swiss Heinrich Dübi in Paccard wider Balmat (1913) and by Graham Brown & Sir Gavin de Beer in The First Ascent of Mont Blanc in 1957, all books unpublished in French and mostly ignored by them. Also, a number of key articles were published in the Alpine Journal, particularly from Henri Montagnier. An American of French and British origins, member of the Alpine Club and friend of Whymper, he had taken over the search from him and found a copy of Paccard's subscription of his ascent narrative; then working with Dübi, they solved the last point left out by Mathews of who discovered the route to the top, Paccard and not Balmat.

At the same time, a CAF French member, Henri Ferrand wrote a long article in La Montagne (1912). Based on Mathews' and Montagnier's work, he analysed in details the perfidious role played by Bourrit in using Balmat to disparage doctor Paccard, contradicted Durier's glorification of Balmat in Le Mont Blanc and restored Paccard as being the sole discoverer of the route to the top thanks particularly to the correspondence and published letters of Paccard and Bourrit with the Journal de Lausanne which ended with the publication of the affidavit signed by Balmat (Journal de Lausanne N°24 12th May 1787) which finally stopped Bourrit's attacks as he could not refute Balmat's testimonial which fully contradicted his version of the roles of the two men.

A key discovery was made by Douglas William Freshfield (a distinguished historian, AC and RGS president) published in his book "The life of de Saussure" (1920): the memoranda of the first ascent writen by de Saussure based on the tale given to him by Paccard when they met, 14 days after the event (p214-216). It does complement well the other written document of the first ascent, the affidavit signed by Balmat.

Among all those authors, Ernest Hamilton Stevens (1864-1945), a London university professor and member of the Alpine Club, will complete the search for the truth, in publishing in the Alpine Club Journal of 1929 a reconstruction of the lost Paccard’s account, using Paccard’s diary, letters, and various testimonials, particularly from de Saussure, Bourrit, von Gersdorf and the discoveries made by his predecessors, particularly the memoranda written by de Saussure found by Douglas Fresfield, etc..

![Mont Blanc from Planpraz]() Mont Blanc from Planpraz

Mont Blanc from Planpraz

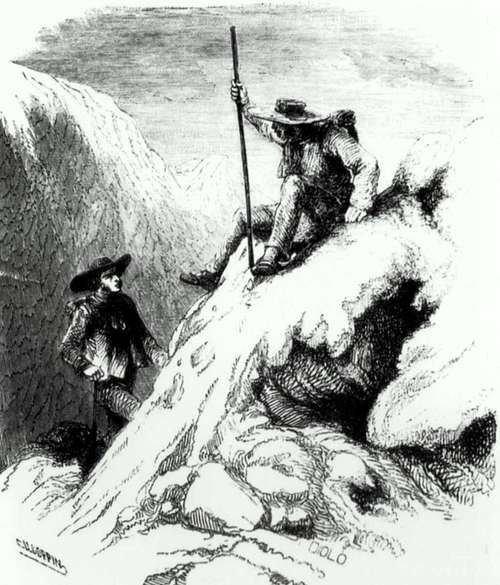

Note that when reading Paccard’s tale of his 1rst ascent of Mont Blanc with Jacques Balmat, one must bear in mind that they had no rope, just a long wooden and heavy ‘bâton’ (a long and heavy alpenstock), some 2,5 m long, iron-pointed, and that they were burdened with Paccard’s scientific equipment, particularly a cumbersome and fragile mercury barometer in a long wooden case. They reached the summit after 14 and a half hours of constant climbing, over some slopes of near to 40° without crampons, and Paccard spent 35’ on the top making measurements in a freezing cold! Whatever the controversy, their achievement was magnificent.

You will find the most significant extracts of this article below published with permission of the Alpine Club. I excluded Paccard and de Saussure’ experiments to concentrate on the history of the ascent and all of Stevens’ footnotes which amount to as much as the Paccard’s text and gives a ‘Sherlock Holmes’ type analysis at its best, both about the scientific measures then taken but also of Balmat and Bourrit’ lies detailed proofs. Interested readers will have to read Stevens's full AJ article which was partially published in the French alpine club magazine ‘Alpinisme’ in 1934 (translated by Claire Eliane Engel), but forgotten since by most French authors, and then fully published in Mont-Blanc Premières ascensions (1770-1904), Editions du Mont Blanc – 2013 by the two historians and novelists Jacques Perret and Michel Jullien, its translation by myself.

The work of all those Sherlock Holmes/Historians/AC members and all great alpinists was crowned with a very complete book, "The First Ascent of Mont Blanc" written by T. Graham Brown (famous for his 1rst climbs of the Sentinelle Rouge, La Poire and La Major) and Sir Gavin de Beer. They completed the analysis of many documents which had been bypassed giving further proofs of Bourrit and Balmat' multiple and lies and fantasies which he grossly enlarged to his benefit as the men involved died (Paccard of course and the guides who had participated in the attempts), which were overemphasized by Dumas and reproduced as the true story by many French and Swiss authors, and still today.

Two examples:

- Balmat's claim to have discovered the route by the Grand Plateau. In his book Relation abrégée d'un voyage à la cime du mont Blanc (and reproduced in all editions of Voyages dans les Alpes, de Saussure wrote: "... Dr Paccard and Jacques Balmat arriving, the first of men in these deserts [the Grand Plateau]." If Balmat had been on the Grand Plateau before, then he would have told de Saussure. This is one of the proofs that having been ont the Grand Plateau the first was a pure invention. Not to mention Balmat stating that on his route discovery attempt, nearing the summit, he saw Courmayeur and heard a dog barking. At the time as no one had been up there such a fable could be believed but after many ascents of Mont Blanc, it was obvious to everyone that on Mont Blanc you cannot see Courmayeur and even less hear a dog barking!

- Balmat's claim that Dr Paccard was so tired that he had to drag him up. In his diary, de Saussure writes: "... When they arrived at the plain [the Grand Plateau]... the guide [Balmat] told him [Paccard] that he would not go further unless he would share the lead from time to time to break the snow, and so he did up to the summit." So the reverse was true as Balmat confirmed in the affidavit Paccard had him sign, and as observers such as von Gersdorf saw and attested.

Whatever, as Eric Shipton did write:

"Theirs was an astounding achievement of courage and determination, one of the greatest in the annals of mountaineering. It was accomplished by men who were not only on unexplored ground but on a route that all the guides believed to be impossible."

T. Graham Brown and Sir Gavin de Beer who so masterly summed up Balmat's lies never "condemned" the man, honouring his feat in ending their book quoting Lord Minto writing in his diary* when J Balmat was still alive and before the legend had been reborn with the help pf Dumas:

"Whatever may be the precise share which each had in discovering the route to be taken, they are both incontestably entitled to the honour of one of the boldest enterprises ever undertaken, and of having dared to face the danger of a night upo the snow at an elevation where it was then established opinion that no one would survive the cold."

* AJ 1892 N° 16, p. 148.

As for Horace Bénédict de Saussure, Paul Guichonnet from the University of Geneva did write in 1988 in the Globe (the geographical review of Geneva): "In 1987 we celebrated the bi-centenary of the de Saussure Mont Blanc ascent... This allowed us to assess even better the exceptional prominence of the man who far more than the Chamoniard Balmat and even doctor Paccard, the first ascensionists of the mountain in 1786, would deserve to be called "Saussure du Mont Blanc"... adding later: "the research I did in the archives of Torino led me to think that it is not at all certain that [the title of Balmat Mont Blanc] has been effectively given to him by the king of Sardinia."

However Graham Brown and sir Gavin de Beer were astounded that this great scientist thinking that Paccard could be a scientific threat finally adopted up Bourrit's false story of the pamphlet in his fourth version of Voyages dans les Alpes and as they wrote: "One man, Professor de Saussure, could have killed the myth at its very beginning, and should have done so .... As an impartial man of science, it was his duty to ascertain the truth and to defend it actively. Perhaps he had let his jealousy of Dr. Paccard override his conscience ... but whatever may have been the factors which moved him, it is not easy to forgive the way in which he finally condoned Bourrit's (venomous) attack, and so clearly that he may almost be said to have supported it. They then showed that de Saussure deliberately ignored in his books, key Paccard's explorations, as Bourrit had done: In June 1784, the first exploration of the Géant glacier in order to see an approach to Mont Blanc, and in September 1784 his attempt by the Dôme du Goûter with his usual guide, Henri Pornet, the first ever on this side, where they covered 28 miles in 36 hours, ascending more than 4000 m, "an amazing feat". Finally de Saussure took Bourrit's side: " At that time, Bourrit was a rising power in the opposite camp, the party of the Natifs... de Saussure, by nature a moderate and an appeaser, had political reasons for avoiding a rupture with Bourrit, and that he therefore refrained from contradicting Bourrit's version... I think also that de Saussure tried to tell as much of the truth as would not annoy Bourrit who does not appear to have resented the priority of guides and hunters, although he did resent the priority of amateurs". (Graham Brown, AJ 57 1949).

And the legend still strives today, an example: In the 1979 French version of "Horace Benedict de Saussure, Premières ascensions au Mont-Blanc" (La découverte/Poche), none of the attempts of Michel-Gabriel Paccard are mentioned and for the first ascent, there are only two sentences attributing the discovery of the route to Balmat who would have " offered him to be his guide"! (p.187)! Most books, comics, TV documentaries that one can read or see today in French still perpetuate the same myth, their prime hero being Balmat. None of those authors/creators seem to have read Mathews, Dübi, Montagnier, E.H. Stevens or Graham Brown and Sir Gavin de Beer, which they never mention. Their sources are taken from Alexandre Dumas, H.B. de Saussure and their French predecessors' books. I suppose that if the AC gentlemen had been French or their books had been published in French, the story would be different today!

![Mont Blanc ascent]() Mont Blanc ascent

Mont Blanc ascentIf

Jacques Balmat exaggerated his role at the prejudice of

Michel Paccard it would be wrong not to continue to celebrate his feat at par with his companion, but in a different light, then and afterwards, as the guide he occasionally became and ‘treasure’s hunter' he remained till his death. Jacques Balmat is an ambiguous hero. He was motivated by the greed of the poor peasant he was, wanting a better life. when reading this story, one must not forget that at the time he was not a "guide", and that Paccard recruited him as a "worker". Also, the de Saussure's reward was not that large : 48 £, when in all he finally got between 500 to 700 £, more than ten times the de Saussure's reward (the largest amounts came from baron von Gersdorf's reward subscription in Germany and 240£ from the king of Sardinia). This explains why Jacques Balmat did not want to share the discovery with any other person and was therefore resented by the guides involved in the attempts. With the money given to him he had a home built for his family and enough land bought from his father (in advance of his inheritance) to significantly improve his peasant's life, but not enough to make him rich. So, he continued to go in the mountains in search of minerals and gold far more than guiding. It should be remembered that due to the French revolution and the Napoleonic wars, little mountaineering activity occurred between 1788 and 1815. Philosophers and tourists had other things to think of than making pilgrimages to the glaciers. Even afterwards the guiding activity remained limited until the second part of the century and the creation of the various alpine clubs: no ascent occurred after 1788 for 14 years and less than 1 ascent every three years occurred until Balmat’s death in 1834, and only 52 parties reached the summit of Mont Blanc up until1850, i.e., in 64 years, extremely far from allowing mountain guiding to be a full-time job. Balmat was credited of 7 ascents of Mont Blanc over his lifetime by H.Dübi of which 4 in 1786 and 1787, and 9 by E.H. Stevens. Therefore, the main activities of Balmat as the then ‘guides’ remained their work as peasants, and occasionally guiding tourists to the 'Glacières' on mules as well as hunting crystals and gold.

Balmat will fall to his death at 72 years old while looking for gold in a highly exposed place, which is a good enough proof of his highly adventurous nature, but also of his immense frustration not to have been able to become if not rich, at least at ease enough as the doctor! A film made by a Chamonix guide for the bicentenary celebration of the ascent in 1986, Denis Ducroz, shows well the subtle and forceful motivations of both men explained in taking into account their different social standing and conditions on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8oJkxbJJuXk.

The end of Jacques Balmat and his family is quite tragic: Before falling to his death in September 1834, his wife had died (71 years old) in March. His son, Gedeon, the only one who worked as a guide had 4 of his kids (from 6 months old to 11 years old) who died from an epidemic, starting from September 1834 to March 1835. In 1841, he was forced to sell all family properties to pay for the abysal debts of his father and he emigrated to the United States (joining his younger brother, Edouard who had emigrated 2 years earlier in the ex French colony of Louisiana, in Louisville) with his wife and three remaining kids, cutting all links with Chamonix. Jacques's two eldest sons had died in the Napoleonic wars, one in Spain, the other one in Germany (Leipzig), both from fevers, leaving him and his wife with no news of what had happened to them for several years. The last of his direct kin, his sister, married a man from Paris and left Chamonix for good. Quite a sad end for the conqueror of Mont Blanc and his kins!

The last word must be given to Michel-Gabriel Paccard who wrote in 1823 to Gottfried Ebel: "I could have obtained legal damages from those who tried to make me look a criminal to have dared to be the first to make an ascent the glory of which they reserved to themselves; but I had been told that there is no greater nobility of soul in preferring to stand up offences than to be harmful in having them punished, that true glory and merit consist in standing up insults and not avenging them."

To end, I will quote Louis Seylaz when in 1957 reviewing The First Ascent of Mont Blanc (AJ62 1957) asked himself the question:"Will Graham Brown and Sir Gavin de Beer's book manage to kill the legend? No matter. Searching the truth is an immortal need in the heart of mankind. And this quest is even more beautiful when gratuitous."

5. PACCARD's LOST NARRATIVE

5.1. My Early Interest in Mont Blanc. The GUIDES’ First Attempt (1775)

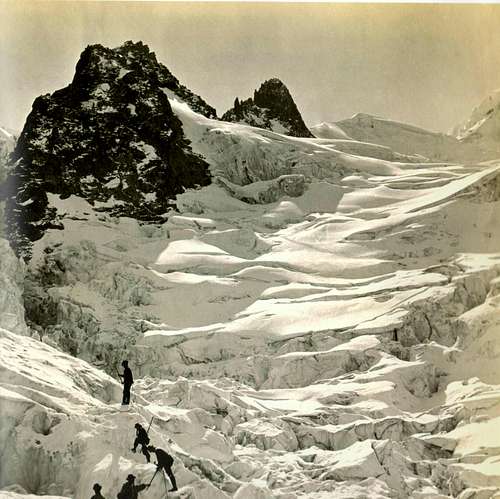

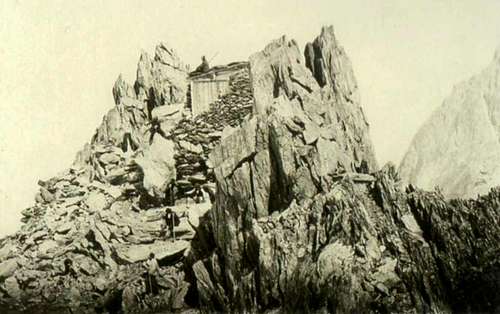

![Les Grands Mulets before 1867]() Les Grands Mulets before 1867

Les Grands Mulets before 1867

“As I was born and brought up in the valley of Chamonix, I have been familiar with its glaciers and peaks from my childhood. My father has long resided there and was the Notary Public of the village. He gave my brothers and me the advantages of a good education – one of my brothers went into church, another in the law, and as I was fond of science, especially of botany, I took up medicine. After finishing my medical studies at Turin and Paris, and obtaining my degree of Doctor of Medicine, I returned home to take up the practice of my profession. I soon became more than ever interested in the study of Nature, alike in her grander phenomena and in her most intimate secrets, and I was often glad to shut my books and leave my room to read the book of Nature herself. I formed botanical and mineralogical collections, made many geological observations, and took barometrical readings for the determination of heights. In 1781, I contributed an article to the Paris ‘Journal de Physique’ on the causes of the varied arrangements of rock strata, and in 1785 I had the honour of being elected a corresponding member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Turin.

Meanwhile I had turned my attention to the problem of ascending Mont Blanc. From my boyhood I was of course aware that M. de Saussure of Geneva, after his first visits as a young man to Chamonix in 1760 and 1761, had offered a reward to anyone who should discover a way by which to reach the summit. Nothing much came of this till 1775, when my cousins, François, and Michel Paccard, with Tissay and Couteran, made a serious effort to achieve this ascent.

I was away from home at the time, but a full account, based on Couteran’s information, will be found in M. Bourrit’s book. The party slept down on the Montagne de la Côte, and next day they followed a path to the top of this ridge and crossed the glacier above it towards the Grands Mulets rocks. After visiting these rocks, they went further up the glacier, and got high enough to see over the Brévent to the Buet, and to sight the lake of Geneva. They stopped where the ice slopes steepened, being overcome with lassitude due to the heat in the snow valley and owing to this and the approach of bad weather they were obliged to return.

5.2. The GUIDES’ Second Attempt (1788)

Sometime after I returned home another attempt by the same route was made by Marie Couttet, Joseph Carrier and 'Le grand Jorasse’ (J.B. Lombard) on July 12th, 1783. They slept on top of la Montagne de la Côte, and had a good crossing of the Glacier des Bossons, but found the rocks [of the Grands Mulets] rotten and difficult. They got as far as where the snow arches over the first rocks at the foot of the little or second Mont Blanc [the Dôme du Goûter].

Here Marie Couttet was taken ill… and they turned back, suffering greatly from the sun –which blistered their skins… and the softened snow towards mi-day. They glissaded part of the way down, and slept for a while on the Montagne de la Côte. In Vol. II of his ‘Voyages’ published last year (1786), M. de Saussure adds that they lost all appetite, and that le Grand Jorasse seriously told him that if he were to try again by the same route, he would take with him nothing but a parasol and a bottle of scent. M. de Saussure concluded that an ascent by this route was hopeless.

5.3. My First Attempt (with M. Bourrit) (1783)

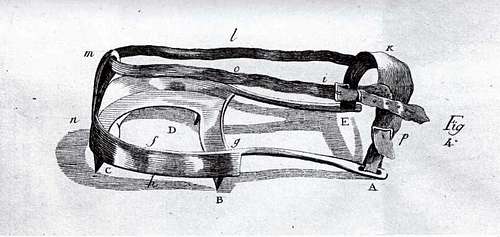

![Going up the Grands Mulets]() Going up to the Grands Mulets

Going up to the Grands MuletsIn September of the same year(1783) M. Bourrit of Geneva – already well known for his travels in the Alps, his books about them, and his mountain drawings, came to Chamonix. M. Bourrit had already paid many visits to our village. He knew my father well, and learned many things about the valley and its history… He was passionately eager to ascend the Mont Blanc, and he invited me to accompany him in an attempt on the mountain, and to bring instruments with me with which to make scientific observations. He had engaged as guides le grand Jorasse, Marie Couttet and J.C. Couttet.

We started on Sept. 15th 1783 at 3 p.m., slept in a hut at la Tournelle, on the Montagne de la Côte – where my barometer had fallen three inches… and next day mounted to the top of the ridge. M. Bourrit did not venture to set foot on ice, but stayed on the ridge, making three drawings, while the guides and I made our way up to the broken part of the glacier, using an axe to cut steps up and down the ice ridges among the crevasses…

Unfortunately clouds came up and covered Mont Blanc and we had to return.

5.4. My Reconnaissance By the Tacul Basin (1784)

Next year, on June 4th, 1784, with Pierre Balmat des Barats, I made a two days’ journey of exploration to the N.E. side of Mont Blanc. We went by the Montanvert…. And some way up the Glacier du Tacul, and slept in a hut on the moraine du Tacul, below the [Aiguille] Noire at a place where two glacier valleys meet… Next morning… we went on some distance until we got on the plain of the Tacul, nearly as far as the [Aiguille] Noire, crossing en route a large number of covered crevasses. The snow began to soften, and we only advanced acouple of gun-shots in two hours, so we decided to go down again to avoid the dangers arising from the melting of the snow bridges over crevasses.

![Ladders passage]() Ladders passage

Ladders passageThe approach to Mont Blanc on this side is difficult. It seems that one must keep close alongside the [Aiguille] Noire, and even over its rocks to avoid the seracs of the Géant. This route then brings one to a glacier, above which is a snow plain, towards with several valleys rise from the direction of Courmayeur. The widest of these runs straight to the foot of the mountain behind Mont Blanc, and appears to bend to the right towards Mont Blanc behind a granite Aiguille which hides it… (Must be la Tour Ronde). Paccard continues with the description of the Brenva valley as it is known now, seen from the glacier du Tacul.

We crossed the snow plain towards a rocky island (le Petit Rognon) to examine these rocks more closely and to find an easier descent, and we rested there behind the Aiguille du Midi, where we saw a herd of nine chamois. Disturbed by the noise we made, they ascended the moraine of a little glacier, got down without our seeing them, crossed the Glacier du Géant, and went up to the glacier de Talèfre… We followed them down and across… We dined on the Jardin below the glacier de Talèfre, where we found some crystals and rock specimens. We then crossed the glacier… and went down to a little plain below the Aiguille du Moine where there are several huts (doubtless for crystal hunters). Then we made our way over… the Mer de Glace under the buttresses of the Aiguille Verte (Known in that time as the Aiguille d’Argentière d’Envers, from ‘Mont-envers’, the pasture at the back, hence the Aiguille Verte) and the Dru, towards the latter…

As a result of this journey I concluded that the approach to Mont Blanc on this side would be too long and difficult from Chamonix, though it might be worth while trying from Courmayeur.

5.5. My Reconnaissance by the Aiguille du Goûter (1784)

On Sept. 9th of the same year (1784), with Henry Pornet, I made an expedition towards Mont Blanc on the opposite side of the mountain, by the Aiguille du Goûter. We started at 3 p.m., crossed the Col of Voza and reached Bionnassay half an hour after nightfall. After supper… and although it was past 11 p.m. we went on through to the Chalets de Miage… We ascended to the Col de Tricot… and Tête Rousse]…Some way beyond the Rocher Rosset, below the base of the Roche Bionnassay [Aig. Du Goûter], about three hours above the little plain, I slipped and nearly came to grief… We went along the side of the Glacier of Bionnassay on the snow… from which stones constantly fall… The route by which to go up the Aiguille du Goûter would be the ridge most to the only with much difficulty, to get up the ridge at the right towards the Glacier de Bionnassay. It would perhaps be possible, but only with much difficulty… It was 6 p.m. when the approach of darkness, the difficulties of the way, and even more the fresh snow, made me resolve to descend… We got back at nightfall to the little plain (where Henry Pornet was waiting for us), and with the help of our crampons (almost the only reference of crampons in the range at that period) we climbed the steep ridge above the huts and crossed the Col de Voza reaching Chamonix at 3 a.m. after two days and nights of continual walking…

This expedition showed me that it might be possible to ascend the Aiguille du Goûter from Bionnassay, but it would be difficult, and dangerous from falling stones.

5.6. M. BOURRIT’s Attempt by the Aiguille du Goûter

![Unnamed Image]() Approaching the Petit Plateau

Approaching the Petit PlateauA week later (16th and 17th Sept., 1784) M. Bourrit made a similar expedition from the Bionnassay valley. Bringing two men with him from Sallanches, he met the grand Jorasse and Marie Couttet, who had started from Chamonix on the 15th, at La Grua where he also engaged as guides Gervais and Cuidet. On the 16th they slept in the last huts on the right of the stream from the Glacier de Bionnassay… Starting again at 1.30 a.m. they crossed this stream by the light of a candle in a paper cone, and halted below the Pierre Ronde, where they made a fire and waited for daylight, a little above the place where Henry Pornet had stayed behind below the cross. When day broke, Couttet and Gervais left the others and went up, towards Chamonix. They ascended the Aiguille du Goûter by the ridge hidden behind the one seen from here. They could not finish the ascent by this ridge, as the rocks overhang, but they cut steps across the snow couloirs to the next ridge, which brought them to the top…

Meanwhile M. Bourrit and the others had come up to the Pierre Ronde below the Glacier de La Gria, and alongside this glacier to the base of the Aiguille du Goûter where the others had ascended. M. Bourrit stayed here more than an hour, sketching the view and the valley of Chamonix. But he suffered greatly from cold and headache– even by 8 p.m. he was very pale – and presently went down to Bionnassay…

Le grand Jorasse thinks he saw the two climbers in the hollow behind the Aiguille du Goûter… They had advanced within 65 feet of the [Vallot] rocks… They say the ridge from the Dôme du Goûter is too steep and would require step cutting. The plain at the end of the Glacier des Bossons [the Grand Plateau] is fine, but it is not possible to climb the snows that cover the points [the Rochers Rouges] of the central chain which runs towards the Aiguille du Midi. They did not suffer from heat, and came down like birds… The crystals they brought down came from the Aiguille du Goûter, but they saw others sparkling in the inaccessible rocks below which they turned back. They think it would be possible to construct a shelter on the Aiguille du Goûter, the top of which consists of flat slate

5.7. M. de SAUSSURE's Attempt by the Aiguille du Goûter (1785)

… On Sept. 13th and 14th (1785), M. de Saussure with M. Bourrit, the latter’s son Isaac, and 9 guides (Pierre Balmat, Marie Couttet, le grand Jorasse, J.M. Tournier, F.Folliguet, J.P. Cachat, F. Cuidet of La Gruvaz, N. Gervais and another of Bionnassay) made an attempt on a great scale on the side of the Aiguille du Goûter. At M. Bourrit’s suggestion, M. de Saussure had had a hut constructed on the Pierre Ronde, over against the lower ledge of the vertical icefall of the Glacier de la Griaz [roughly 400 yards below the actual Tête Rousse refuge], where M. Bourrit had been the previous year… M. de Saussure had come from home incognito, giving out that he was going to the Little Saint Bernard. The whole party… reached the hut at 5 p.m. Two men carried two mattresses weighing about 50 lbs. each; two others took about 50 lbs. of wood each, which was enough for moderate fire for two nights; two others carried 6 sheets, 5 blankets and 3 cushions; two porters carried the provisions (in a basket for the back and a skin bag),and a third took the ridge pole of the hut…

The hut was roofed with flat stones, and afforded room for five persons. The others slept round a fire made a few feet from the hut. The party spent a fairly restful night, except young Bourrit, who was sick several times. Next day, Sept. 14 (1785) they started at 6.20 a.m., reached the foot of the Aiguille du Goûter at 8.30 a.m., and ascended the ridge… They went on till a few minutes past 11, to where the Aiguille is much steeper and seems properly to begin. M. de Saussure then sent on Pierre Balmat and Cuidet to explore the way. They climbed up steeply for an hour and a quarter… (640 feet). Pierre Balmat shouted down to them that there were two feet of fresh snow ahead.

M. de Saussure, who has always shown a great dislike of snow climbing, though he is thought to go on well on rocks, decided to stay where he was and make experiments. Everyone was glad except young Bourrit, who seemed to want to go on, though he had taken nothing but a little brandy and water… M. de Saussure and his party started down soon after mid-day… For this descent M. de Saussure had himself tied up like a prisoner; he was fastened with a rope under his arms to Pierre Balmat and F. Folliguet behind, while Couttet showed him where to step in front. M. Bourrit leaned on Gervais’s shoulder while Tournier held him by the collar. At difficult places a bâton was held as a handrail for M. de Saussure to lean on, both going up and coming down. Young Bourrit who was unwell while going up, held on Cuidet’s coat, but needed less help than the others on the descent. They reached the hut at 6p.m., where the guides were paid off. They received 6 francs a day, and the whole expedition cost M. de Saussure 800 francs… Nothing more was done that year.

5.8. The GUIDES' Attempt by the Dôme du Gouter (1786)

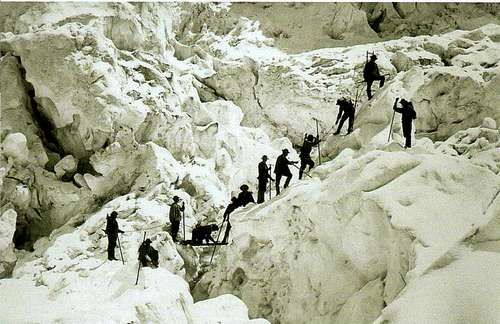

![Crampons used by de Saussure]() Crampons used by de Saussure

Crampons used by de SaussureNext summer, five guides made an attempt to test the relative advantages of two ways to the Dôme du Goûter as a route to the top of Mont Blanc. Joseph Carrier, J.M.Tournier and Fr. Paccard (my cousin) slept comfortably in a shelter on the Montagne de la Côte, where Joseph Balmat of les Baux joined them uninvited. He was not really a guide but a crystal hunter, who wanted a share in the reward offered by M. de Saussure, which it was plain that to the others were hoping to gain. They naturally looked somewhat askance upon him. Next morning, June 8th1786, they started early for Mont Blanc. On the same day, Pierre Balmat and Marie Couttet, who had slept in M. de Saussure’s hut on the Pierre Ronde above Bionnassay, went up from there to the Aiguille du Goûter. There was still much snow low down, on the Brévent and the Montagne de la Côte, but in the morning the snow bore well. The party that started from the Montagne de la Côte were the first to arrive on the Dôme du Goûter and to reach the final summit of Mont Blanc at the plain [Col du Dôme]. According to what they say, they went on to the rocks that can be seen from Chamonix [the Vallot rocks]. They assert that it is impossible to go that way to the top – on the one side is the precipice above the Vallée Blanche, on the other are steep and broken snow slopes which protect it from approach. It seems from here that it would be better to approach behind the Aiguille du Midi. They built a stone man on the [Vallot] rocks which should be visible from the mill at les Pras, but saw nothing of the one said to have been built by Cuidet and Couttet – on the contrary there was not a stone displaced at the spot pointed out by Couttet as that at which they had made theirs… The party from Bionnassay arrived on the Dôme du Goûter after the other four, who had seen them on the shoulder of the Aiguille du Goûter looking like two chamois. The parties shouted at each other, and the two ascended to join the others, but were very tired, especially Pierre Balmat des Barrats. Almost all of them felt a kind of faintness. The one from les Baux was revived by some fresh water which he found on the rocks, and he went on alone up these rocks looking for crystals... The others, without waiting for them, turned to go down – bad weather was coming up and hail began to fall. They reached Chamonix at 10 p.m., having come down pretty much to the top of the Montagne de la Côte by night.

Balmat stayed a long while behind the others, and was caught by the darkness of night while still on the snow. He was following the tracks of the others, who had been sinking in to their knees, although the snow was hard in the morning. Having felt with a bâton a crevasse which the others had jumped, and not being able to see clearly, he dared not go further, but putting his bag under his head, his handkerchief over his face, and his snow shoes under his back, spent the night on the snow. Next morning his clothes were frozen, but he got down safely to Chamonix by 8 a.m. Most of the members of the party were sun burnt – Tournier was as red as the great fire at les Pras. His skin came off in scales a few days later.

![Unnamed Image]() Michel-Gabriel Paccard, croquis de l'itinéraire de 1786 au sommet du mont Blanc envoyé à Johann Gotfried Ebel, 1823

Michel-Gabriel Paccard, croquis de l'itinéraire de 1786 au sommet du mont Blanc envoyé à Johann Gotfried Ebel, 1823

Note: On the 18th of August 1786, Charles Bonnet, de Saussure uncle, wrote to count Bielke of Stockholm mentionning the following: "The new route he [Paccard] has discovered ... is very different from the one which my nephew Saussure had followed last year... My nephew has received a very careful map of the new route, which he showed me a few days ago, and he is preparing to take advantage of it shortly, in order to follow the steps of the doctor..." (source: Charles Mathews, The Annals of Mont-Blanc, 1898). This map sent by Paccard to the geologist J.G. Ebel (kept in Turin archives) stayed unknown to all historians up to recently and proves that contrarily to what was believed, the first ascent route was the same as the de Saussure's one i.e. getting to the Small Red Rocks by climbing above the Upper Red Rocks and below the rock at the top of the Grand Plateau and not on the slope between the Upper and Lower Red Rocks. The initial route was identified from one sentence in de Saussure diary which lacked precision (the rocks bands involved were then unamed and the "translators" forgot to notice that de Saussure indicated "[the route] goes above the rock to the left" which corresponds to the position of the Upper Red rocks and the rock band above the Grand Plateau ("the rocher enclavé "in Paccard's map) and not the Upper and Lower Red Rocks which are one above the other) and so was interpreted wrongly in the translation, (including by Stevens). It is not a major matter, but this fits far better with von Gesdorf' sketches and map as well as Bourrit's map and make sense as nor Balmat, Bourrit or anyone else ever mentionned that he took a different route on the 2nd and 3rd ascents he made. Technically it does not make much difference, taking one or the other route very much depended on the size and difficulty to get over the crevasse at the foot of the passage. The authors of Mont-Blanc 1786 (Philippe Campione and Catherine Guerin - Epigones, 1992) who must have had access to Paccard's map were the first to describe this part of the route properly: "Listen Balmat, I know the route to follow, look, by the slope of snow and ice secured by the Red rock, exactly between the Upper Red Rock and the enclave rock at the top of this Great Plateau."![Unnamed Image]() La voie Paccard

La voie Paccard

5.9. Discussion of possible routes to the summit

![Unnamed Image]() Unnamed Image

Unnamed ImageThis party thus confirmed the opinion of M. Bourrit’s guides in Sept. 1784, that the ridge leading from the Dôme du Goûter towards the summit was too steep and narrow to afford much hope of success in that direction. My thoughts therefore turned again to the possibility of finding a way over the snow slopes above the Glacier des Bossons. During the last three years I had often examined this part of the mountain through the telescope from the Brévent. It was pretty plain that it would be possible to advance from the top of the Montagne de la Côte to the great snow plain [the Grand Plateau] immediately below the summit, though the crevasses in the lower part of this route would probably cause a great deal of trouble. Three parties however – in one of which I had taken part – had already, as related above, gone some distance towards the great snow plain. But the summit rose far above this plain, and the final slopes were evidently high and steep, and no one had yet got near them. Marie Couttet, who had examined these slopes from the Dôme du Goûter, thought them hopeless.

It seems to me, however, that one might be able to climb them by a broad bank of snow that slopes steeply up to the left from the Grand Plateau, between two tiers of perpendicular rocks, towards the eastern shoulder of the mountain, from which, on turning to the right, one would have an easier incline to the top. Unfortunately the bank of snow was exposed to avalanches from the ice cliffs above it. I observed, however, that when the snows were low and settled the risk of avalanches was small. Even if that did not prove to be the case, it would be possible to effect another route from the Grand Plateau along the footof the truncated rock [the Rochers Rouges] i.e. the tiers of rocks whose cut-off top supports the bank of snow referred to before, passing round this and the Rochers Rouges to the gap above the Glacier de la Brenva and thence to the right to the top. Either of these routes would be a very long climb, and I thought it almost certain that one would have to sleep high up on the mountain. Now Balmat’s adventure had shown that this was possible without excessive risk, and I determined to make another attempt. My own guide was away, and so when Jacques Balmat offered his services, as he seemed a strong and enterprising fellow I accepted his offer and engaged him as a porter. I should have preferred to take another man or two to share the labour, but Balmat was averse from this, wishing no doubt to earn the whole of the reward offered by M. de Saussure. Of course he knew that I should claim none of it.It was necessary to wait for good weather and a favourable state of the snows. At last, after three weeks’ unsettled weather, we were able to start on Aug. 7th. I had told Balmat I proposed to go by the Montagne de la Côte. This led him to think I might try again by the guides last route, viz. that by the Dôme du Goûter… in view of his experiences on June 8th he did not think there was much chance of success by that route. I explained I had reconnoitered the routes by the Glacier du Tacul and by the Aiguille du Goûter, and had rejected both, but I now intended to keep straight on from the Montagne de la Côte to the Grand Plateau, and find a way up from there. Balmat was then in favour of this as the likeliest of the three routes I had in mind.

5.10. From the Montagne de la Côte to the Grand Plateau

![Les Grands Mulets shelter]() Les Grands Mulets shelter