Introduction

![Dark Angel]() Dark Angel-- by Sarcasticseth

Dark Angel-- by Sarcasticseth![Deep Tank-- Summit Area]() Tinaja

Tinaja

At Dark Angel, I found that my camera lens did not give me an angle wide enough to photograph the full formation from the trail looping it. Instinctively, I backed up, off the trail, until I had the right composition.

"Hey man, you're stepping in that cryptobiotic crust they're trying to get people to stay off. That shit's alive and you f------ kill it when you step on it." Or something like that.

My first impulse was to tell the guy what I thought he should do to himself. My first look at the guy confirmed it; he was the grungy-looking, uber-hiker type looking as though he'd smoked too many joints in his life and said "Man" and "Dude" way too many times, the kind of guy whose appearance can make me embarrassed to admit I'm usually on the side of the environmentalists.

But then I remembered the sign and recalled some more details from it. And I knew he was right. So I held my tongue. I still took the picture; after all, I was already there, so there was no reason not to take the picture, but then I guiltily returned to the trail, trying to stay on rocks or step into my own footprints.

So what had I done wrong? Well, I had done my own little part to kill the desert.

It is sometimes amazing to consider that the world's harshest places are also often among its most fragile.

Walk into the desert. All around, you see rock, sand, and scrub. Dawn's first light may bring a welcome end to night's chill, but within minutes, the summer sun induces sweat. Within hours, if you are not properly hydrated, you could die, even if you are within sight of a paved road and your car. It has happened before and probably will again; a morning jaunt into a sand-dune oven, where ground temperatures can quickly approach water's boiling point, leads to heat exhaustion, or heatstroke, and then death.

This is no place for a human. Get out.

Now take a walk back in. This time, look a little closer. Ignore, for a few minutes, the big rock outcrops that by now are anvils under the sun. Instead, notice the tiny wildflower here and the crawling insect there. Notice the tracks of rodents and lizards. Notice the shiny leaves on that silvery plant-- the leaves reflect sunlight to keep the plant (relatively) cool and allow it to survive life in this inferno. Notice the scurrying of a kangaroo rat among the dwindling shadows-- it never drinks a drop of water in its life even though it lives in an environment that builds a thirst the way a blizzard builds a desire for a warm, dry place; instead, it creates its own moisture from the food it eats.

No, this is a place of life-- small life, hidden life, quiet and slow life, but life nonetheless. I am not a fan of the

Jurassic Park films, but one line from the second film has always stayed with me: "Life will find a way." Indeed it does.

So stay, properly prepared, that is. Stay awhile and observe the life. Stay awhile and make yourself a part of it while you can.

But as you explore, watch where you step and what you do; your ignorance or carelessness can make an impact that may last for decades.

Blood and Bones

The desert ecosystem is a complex one, and it would be beyond my knowledge and time restraints to explain the ecology of just one particular desert. Here, I focus on just two vital and fascinating parts. Consider this article an overview, not an in-depth scientific exposition, which would probably be most thorough and most painfully boring (and confusing) to read. You can, though, get more details about cryptobiotic crusts by using the links at the end of this page.

Blood

![Sea Monkeys? In Nevada?]() Tinaja-- photo by lcarreau

Tinaja-- photo by lcarreau

Without a doubt, water is the true lifeblood of the desert. Even in such a parched landscape, the story of water is all about-- the green islands around washes, the eroding hoodoos and clay buttes that can literally change after every rain, the flood-carved slot canyons with walls of slippery-smooth stone.

Running water is rare. So is standing water. But nature has its ways of getting water where it needs to go and to those that need it. Yes, there are the occasional rains and snows, but the water they bring goes quickly-- evaporated, run off, or sucked up. So what are some other ways for the desert, especially its animal denizens, to drink?

The spring-fed oasis-- It is the classic desert example, a fine display of which can be found at Quitobaquito in Arizona's Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument; there, a tree-lined pond sits in the middle of one of the hottest, driest places in North America, and a visit to the spring's shaded shores is almost surreal.

Another outstanding desert spring that is relatively easy to reach is Saratoga Spring in California's Death Valley National Park (see picture below). Standing there among grasses and shrubs and the constant calls of insects and birds, you will have to look up and away to the scorched peaks around you to remind yourself that you are in one of the most hostile environments in the world.

![Desert Reflections at Saratoga Spring]() A spring, not a tinaja.

A spring, not a tinaja. Shallow depressions in rocks, they collect rainwater and provide short-lived sources of hydration and breeding grounds for animals as diverse as insects and frogs and predatory mammals.

Pothole is a broad term; for example, some slot canyons have deep holes in their floors, and these floors are often referred to as potholes. Here, I refer to a pothole as a depression a few inches deep atop a rocky surface.

![Old Rag-- Summit Pothole]() A pothole, not a tinaja, and not in the desert, either.

A pothole, not a tinaja, and not in the desert, either. is Spanish for a small pool in a rocky hollow (

source).

Hueco is Spanish for "hole, hollow, gap."Larger and deeper than the typical pothole but still ephemeral and too small to be counted even as a small pond (though some can be the size of a small pond), these, like the oases, are true desert gems. Erosion, usually water-based, carves bowls into rock surfaces. Then rainfall and snowmelt fill them. Depending on the climate and the depth, these tanks can hold water anywhere from days to months; some almost never go dry.

![Tinaja below summit pyramid]() Tinaja-- photo by Anya Jingle

Tinaja-- photo by Anya Jingle

Tanks are not scarce but are nevertheless uncommon enough to be a real treat for the unsuspecting hiker or climber. Some, like Ernst Tinaja in Texas's Big Bend National Park, or the Calico Tanks in Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area just outside Las Vegas, Nevada, are well-known and have popular trails leading to them. But many more, really most, await those who are willing to do a little wandering. The second one I ever saw (the first was Ernst Tinaja) was one I found purely by accident; in Arizona's Superstition Mountains, I had hiked a trail to a viewpoint and decided to take a more direct but more rugged way back, and along the way I found a deep-looking tank filled with dark water (see below).

These basins all play a critical role in the survival of wildlife. Even brine shrimp, known to some as

sea monkeys, can make a life in them. In Nevada's Red Rocks, the tinajas help sustain the population of bighorn sheep. Life from algae to cougars finds sustenance in these places.

But they can also be graves. Smoothed out as they are from running water, including flash floods (many tanks have been scooped out of the floors of slot canyons, though some are atop desert mountains), tanks can be death sentences for those careless or unlucky enough to fall into them. At Ernst Tinaja, even deer and mountain lions have drowned. Humans have died in tanks and deep potholes, too.

Protecting the Tanks

In many places where tanks are found, regulations prohibit swimming and wading. The oils from the body can upset the ecological balance of these small worlds. Plus, for reasons outlined in the previous paragraph, it's just

safer to look and not touch. Bottom line, whether regulations exist or not: it is best to do nothing more with the tanks than sit by them and/or photograph them. Don't put your short-term thrills ahead of the long-term health of a delicate ecosystem.

![Desert Water Tank]() Tank-- Superstition Mountains, AZ

Tank-- Superstition Mountains, AZBones

The bones are the structure that supports the body. Without bones, the body collapses.

The desert has its bones, too, but they are far more delicate than those that support our bodies. In many deserts, and in many other places, too, including the tundra, the skeleton is an exposed layer atop the rocks and soils and sands.

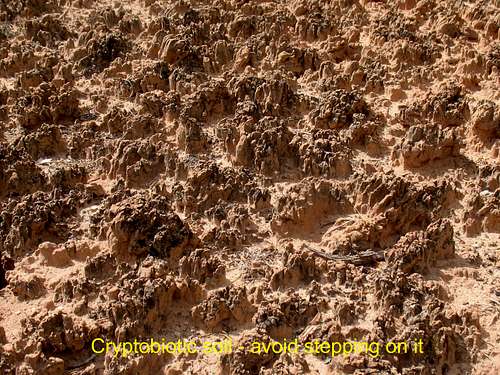

If you have ever been to southern Utah, especially to Arches and Canyonlands National Parks or the San Rafael Swell, you have seen the dark soil that covers so much of the area. That dark soil, which is actually a crust atop the desert soil, may look like the remnants of a fire, but it is in fact an organic community that, after water, anchors the living ecosystem here. This crust is known by various names-- among them are

cryptobiotic crust, cryptogamic crust, biological crust, organic crust and

microbiotic crust. Here, I will refer to it as the

cryptobiotic crust.

![Capitol Reef Cryptobiotic soil]() The crust

The crust

Cryptobiotic crusts are actually found in most of the world, and the colors vary by region, but it is in arid regions and places where the growing season is short (like on the tundra) that the crusts are the most fragile. They feature prominently in American landscapes such as the Columbia Basin, the Great Basin, and the Sonoran Desert, but they seem most on display (because of the intensely dark color and the large concentrations of them) on the Colorado Plateau, which covers most of southern Utah and parts of northern Arizona, western Colorado, and northeastern New Mexico. In fact, it is in many of the Utah parks that signs and park newspapers inform visitors of the crusts and ask them to avoid stepping on them.

The cryptobiotic crust is a collection of mostly algae (green and brown), cyanobacteria (formerly known as blue-green algae), lichens, and mosses, though other organisms can be there as well. As time passes, the crust grows both out and up; some mature crusts can reach "heights" of about four inches (app. 10 cm)-- this is only what is above-ground.

All the organisms play a role, but the chief actors seem to be the cyanobacteria. More on their roles is detailed below, but here's some food for thought: these microscopic organisms are believed to be deserving of much of the credit for life on earth. Scientists believe that "thick mats" (from the Canyonlands page linked to in the lasts section) of cyanobacteria converted the planet's atmosphere to an oxygen-rich one from one rich in carbon dioxide. Now that's a little humbling, isn't it?

![Red Outcrop and Tinaja]() A world from a puddle?

A world from a puddle?Value

So who cares? What's the big deal?

There are two main functions the cryptobiotic crust fulfills:

Stabilizing the soil-- Many of the organisms comprising the crust work on their own and together to cement the soil to themselves, making it more resistant to erosion by wind and water. That, in turn, provides a better foundation for plants to grow. Furthermore, plants growing from the crust do better than the same species growing in "regular" soil nearby; the "crust plants" tend to have more nutrients in them, grow stronger, and live longer.

It would become an exercise in plagiarism or clever paraphrasing to attempt to explain the intricate workings of the crust that make it a boon to plant life, but here is a quick account: when wet, the cyanobacteria move around and create a web-like array of fibers, which join loose bits of soil together and make it remarkably resistant to wind and water erosion. The cyanobacteria also aid in nitrogen fixation, providing a crucial crutch to plants growing in an environment that otherwise has low levels of nitrogen.

Retaining Water-- Scientists have found that the healthier, more jagged crusts allow better infiltration and retention of water than do crusts that are less pristine or less developed.

Damage and Its Effects

Aside from long-term changes in climate, the greatest threats and damage to the cryptobiotic crust come from-- this will surely be shocking-- humans or human-related activities: stepping on the crust, ORV use, and cattle grazing. It is easy to find damaged or destroyed crusts close to popular hiking trails in national parks and on public lands open to "mixed usage," a term that often means grazing, mineral extraction, and/or motorized vehicles are allowed.

Another threat is fire. Severe fires can cause significant damage to the crust. At the same time, though, soils protected by cryptobiotic crusts recover from fire more quickly than those not so protected do.

Fire is part of the natural cycle. It can be argued both strongly and well that fire should be allowed to take its course in the wilderness. Indeed, fire suppression has played a major role in some of the catastrophic wildfires of recent years.

It is harder to argue, though it can be done, that trampling by tires and feet, both human and bovine, are part of the natural cycle in the desert. The problem with the trampling is this: the crust can take decades to develop to maturity but is so fragile that it can take seconds to destroy it; some organisms can recover quickly, but others can take over a century to do so. And while it can be said that the grazing is necessary because of our food needs, it really cannot be said that the other forms of human-caused damage occur solely for the sake of a better picture or a little fun.

When the crust dies, the soil is vulnerable to invasive species and being washed away. And so can die the ecological integrity of the ecosystem. Anyone who passed basic Life Science in high school should be able to understand this. Will the whole ecosystem collapse if one patch is disturbed? No. But every little bit helps, or hurts.

Caring for the Crust

Wilderness conservation will help, of course, but since humans pose the greatest short-term threats (geologically speaking) to the crusts, it is humans that must individually choose how to act. Stay on established trails. When that is not an option, make an effort to hike through washes and on rock slabs as much as possible. My steps across the crust back in 1997 are steps I wish I could take back, but I can't do that. However, that was the last time I stepped on the crust except when I had no other choice, and those times when there was no other choice have been very few and brief; I can count them on one hand. It's understandable that a yearning for wilderness and splendor will take you from the established trails, but out in these fragile parts of the desert, it's not like bushwhacking through briars and deadfall, and we can all take a little extra care. If your route finds you having to engage in extensive crust-crunching, you might consider the bigger picture and look for a friendlier way or another destination entirely. We shouldn't pursue our fun when that means we harm what we love.

Final Words

As you can (hopefully) see, what can kill you so easily, you can kill easily as well. The difference is that nature is what it is-- sublime yet subtle, lovely yet deadly, simple yet complex, and always indifferent-- and therefore cannot be called to account for the harm it does, while we, through ignorance or malice or deed, do destroy what we cannot replace.

So breathe in the wonders and the secrets of the desert. But tread lightly. Just one step-- and that one step is never the only one since everyone taking it thinks the same thing: "What's one step, one wildflower picked, one rock collected...?"-- can have consequences. That "one little thing" may affect the fate of a world.

Comments

Post a Comment