Background

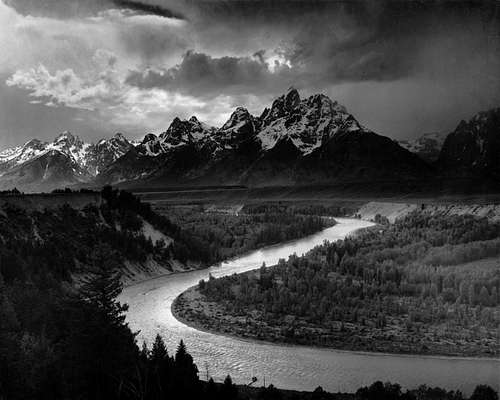

![Ansel Adams, The Tetons and the Snake River (1942)]() Ansel Adams, The Tetons and the Snake River (1942). Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the National Park Service. (79-AAG-1)

Ansel Adams, The Tetons and the Snake River (1942). Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the National Park Service. (79-AAG-1)Climbing the Grand Teton was a long-held goal for me. I was captivated by the the Teton Range long before I visited for the first time in 2012; I still easily recall the wonder I felt when I first saw the legendary Ansel Adams photograph The Tetons and the Snake River as a teenager. Back then I didn't think that I would ever climb any of those peaks, only that, more than any other landscape I had ever seen, the Tetons had an unmatched sense of grandeur and majesty. As the years passed that sense of wonder faded a bit from my memory. As a result, the first time I found myself there it wasn’t even my first-choice destination - the trip I was planning on taking, with my then-girlfriend, was to RMNP, but it was derailed at the last minute by the High Park fire. We chose the Tetons essentially because it was the next closest national park either of us had heard of. So we loaded up the car and pointed it that way. The seven days we spent backpacking in the park’s various canyons were profoundly formative for me. Suddenly my outdoors goals, previously nebulous, came into sharp focus: I wanted to get to those high places. I started learning to trad climb for the sole purpose of climbing the Grand Teton (which, as we’ll find later, is a little ironic). “Next year,” I thought, “I’ll be back.” I didn’t have any idea how rarely the stars align to make something like that happen. It took rather longer than I expected.

![Grand Teton, June 2012]() Grand Teton, June 2012

Grand Teton, June 2012(What follows until the next blue header is some personal backstory and has little to do with actually climbing the Grand. If all you’re after is the brass tacks of a trip report then by all means scroll down. But if you’re interested in understanding why this particular climb was so important to me, read on.)

The next year, after a great deal of planning and dreaming and anticipation, I was in the same car with the same girlfriend, about to pull out of the driveway and head to the Tetons. This trip was supposed to be particularly significant: it was my last long vacation time before starting a three-year graduate program, and a short respite for my girlfriend, who was helping to care for her terminally ill father at the time. As I started the car, however, she decided that couldn’t bring herself to leave him. So we didn’t take the trip. Of course I didn’t resent her for this; my little dream was the least significant casualty in a very long list. He passed away a few months later.

The year after that, I wanted to take advantage of the two weeks my graduate program allowed for vacation in the late summer. So we planned another trip, this time a bit shorter. Unfortunately, that one never got off the ground either. Same car, same girlfriend, but this time she had decided to move several thousand miles away and end all contact between us, immediately; she delivered this news to me the night that we were supposed to leave together on the trip. Needless to say, we didn’t make it out to Wyoming. Now, looking back, perhaps I should have gone alone, but the emotional difficulty of losing a very significant relationship kept me here in Wisconsin.

It would be hard to overstate how deeply the loss of that relationship affected me. Not only did I lose a best friend, but I lost a consistently stoked hiking/backpacking/climbing partner. If you’ve ever lost a relationship like that, you know how much it all hurts. You want to get outside and forget about it, but with whom? To make matters a little worse, only days after all of this happened I broke my foot in a cycling accident.

![Broken Foot]() There's your problem.

There's your problem.

So I spent several months in a boot. And to make matters much worse, I was right in the middle of my medical didactic year, meaning that I was putting in 80-90 hour weeks (40 hours of class, 40-50 hours of studying per week) every week. And so the dream was deferred another year - or several, for all I knew at the time, as my medical rotations would start the following year and I had no idea where I would be.

Fast forward a few months. I got really lucky (and I don’t want to make it sound like this is the only time anything good ever happened to me - I’m incredibly fortunate in a number of other ways): I was selected to spend the month of August rotating in the urgent care clinics in Yellowstone National Park. I would live at the Lake Clinic, only a few hours from the Tetons, and have several days off per week. I was determined to fulfill my dream this time. I bought Training for the New Alpinism, developed a training plan, and from January to August put in a lot of sweat and effort.

A stone's throw!

The Climb

I had tried to find a partner for the Grand since the first day I arrived for my rotation, to almost no avail. I met two great guys (Tyler and Austin) at the Jenny Lake Ranger Station on one of my trips down to the Tetons and attempted the Upper Exum with them, but we were turned around by some nasty weather.

![Jim, Tyler, and Austin]() Packing for a night at the Lower Saddle and the Upper Exum

Packing for a night at the Lower Saddle and the Upper Exum![Garnet Canyon]() The view down Garnet Canyon. We didn't get much of that precip, but a storm hit the range a few hours later.

The view down Garnet Canyon. We didn't get much of that precip, but a storm hit the range a few hours later.Before I knew it it was my last week in Yellowstone. I had spent nearly a month hiking, backpacking (Tetons, Yellowstone, and the Beartooths), and nontechnical mountaineering (Long's on the way up from Wisconsin, Symmetry Spire) throughout Greater Yellowstone and elsewhere. It was truly one of the best times of my life, but somehow the whole thing would have felt incomplete without fulfilling my dream of climbing the Grand, or at least giving it one more good try.

![Symmetry Spire from Hanging Canyon, August 2015]() Symmetry Spire from Hanging Canyon

Symmetry Spire from Hanging Canyon![Beartooths from the Beaten Path]() Beartooths from the Beaten Path

Beartooths from the Beaten PathWith that ticking clock in mind I started watching the weather very closely. I told myself that I would only consider soloing if the route was likely to be in perfect shape. And it looked like it would be just that the morning after my last day of work, Friday the 28th - the trouble was I needed to be back in Wisconsin ready to start another rotation on that Monday! Then the final piece of the puzzle fell into place: my dad, a truly selfless person, offered to fly into Jackson on Saturday afternoon to help me drive home. This was no small feat, financially or in terms of the time he was giving up. There are a lot (A LOT) of people without whose support I would never have been able to do this, but I think he deserves special credit because the whole thing might never have happened if he hadn't removed that last little hurdle for me.

Now it’s the morning of Friday the 28th. I wake up around 5am, work my last 12 hour shift at the urgent care at Old Faithful, drive back home, pack up the car, say my goodbyes, eat dinner, drink a big cup of coffee, and drive to Lupine Meadows. I ponder my memorized version of the Owen-Spalding, drawing on a bunch of trip reports, the Ortenburger guidebook, Mountain Project, and the Wyoming Whiskey page before all that content disappeared. My mantra is “be ready to turn around at any time; never make a move you can’t reverse.” With that in mind I start from the trailhead around 1:30am. About 5:30am I’m at the Lower Saddle, a little tired (awake for 24 hours at this point) but feeling good.

![Waiting for Sunrise at the Lower Saddle]() Waiting for Sunrise at the Lower Saddle (I'm the goon on the right). Photo credit: Quintin Barney

Waiting for Sunrise at the Lower Saddle (I'm the goon on the right). Photo credit: Quintin Barney

From there things slow down a bit, as it’s still dark enough that the easy way to the Upper Saddle isn’t obvious - and of course the altitude was affecting this flatlander a little. After a few slight detours I’m at the Upper Saddle.

After a brief rest and a few more steps upward, I'm staring at fifty feet of rock that I’ve turned over in my head countless times over the past several years: the Belly Roll, Crawl, and Double Chimney. For whatever reason it’s deserted, so I start moving. To my surprise, it’s underwhelming. A few years of trad climbing on Baraboo quartzite made the Teton granite feel like glue under my feet.

The Belly Roll and Crawl the day I climbed them (neither of these people is me). Photo credit: Quintin Barney

The Belly Roll and Crawl the day I climbed them (neither of these people is me). Photo credit: Quintin Barney

After navigating the Owen Chimney (a little icy at the top!) and Sargent’s via the “hidden exit” it’s smooth sailing to the summit.

![Finally on the Summit]() Finally on the summit. I was up there barely long enough to have someone snap this - look at those clouds!

Finally on the summit. I was up there barely long enough to have someone snap this - look at those clouds!(And yes, that is bear spray. I caught so much shit from people for having it out. Why would I take the time to put it away when I'm going back down anyways?)

![Grand Teton Geodetic Marker]() Grand Teton Geodetic Marker

Grand Teton Geodetic MarkerNow it’s about 830am. I make small talk on the summit with an Exum guide (who was truly an abrasive piece of shit, although I can't badmouth him too much as I rapped on his rope) and his clients. The clients wonder whether or not I'm scared of the exposure. “It feels a little staticky up here,” says a JHMG guide who walked up a few minutes later, and we decide to start downward. Six hours later I’m throwing my pack into the back of my car - an hour late to pick up my dad from the airport. At this point I've been awake for 33 hours, 13 of which were spent moving almost constantly. On some level I can hardly appreciate that I've finally done it. This was so much more than a climb for me - it was a symbol of having overcome a very difficult year and the fulfillment of a dream that stretched back much farther than that. It's hard to put into words, but if you've felt it you know what I'm talking about. I shed a few tears on the way to the airport. Now I'm back home dreaming of bigger things.

Brass Tacks

Preparation:

Training for the New Alpinism. There’s no alternative and no reason to read anything else. This book turned me into a monster compared to what I was before. I did the Keyhole on Long’s Peak on my way up to GTNP in 9 hours car to car (after only 2 days above sea level), the East Ridge of Symmetry Spire in 7 hours car to car (no ferry), and this climb on the Grand in 13.5 hours car to car. How I gauge a “hard day” is completely different now; I recall my first time backpacking in Glacier, when a 12 mile day with 2500 feet of elevation gain seemed like the end of the world. The Grand was +7000 -7000 and 14 miles! Not only did my increased physical capacity give me the ability to do what I wanted, I could keep enough in reserve to deal with the unexpected. I was tired after that day, of course, but not dangerously so. I had more gas in the tank just in case, and that’s important. Now obviously these times aren't objectively impressive - I'm not under the impression that I'm ever going to set records, and there are probably countless people who have never trained that could put up much better times. But the difference between the athlete I was in January and the athlete I am now is striking.

I consider all of the technical rock climbing I've done as preparation for this climb as well. I think it's the best way to learn how to move confidently on rock, which is a big part of what allowed me to be successful here. I moved quickly even on the highly exposed sections because of this particular type of preparation. Of course it is a little funny that I learned to trad climb with this goal in mind and then didn't even carry any pro with me when I finally did climb it. But the experience was still useful.

I used all the resources I could find on the climb itself and the conditions, like the ones I mentioned above. For weather, etc., there are a lot of links on the Wyoming Whiskey website that I found helpful when trying to decide whether or not I was likely to encounter much ice. There’s a weather station on the Lower Saddle and some information for determining the relationship between the temperature there and the conditions on the summit, and a few NWS products that give projected temperature on the summit and the likelihood of precipitation. The more you know going in the better, but obviously that storm might come a few hours earlier than NOAA said and that’s just how it goes.

Mountain-Forecast Summit Forecast: http://www.mountain-forecast.com/peaks/Grand-Teton/forecasts/4197

NOAA Forecast for Lower Saddle: http://forecast.weather.gov/MapClick.php?lat=43.739&lon=-110.8018&unit=0&lg=english&FcstType=graphical

Lower Saddle Weather Station (offline for now): http://mesowest.utah.edu/cgi-bin/droman/meso_base.cgi?stn=TETWY&unit=0&timetype=LOCAL

I feel obligated to mention that the best way to do this is with someone who has already done it before. And believe me, I tried. But sometimes you have to work with what you have and accept the risks that come with that.

Gear:

- Mountain Hardwear Scrambler 30L

- 60m 10.2mm dynamic climbing rope (it’s all I have, so that’s what I used - a skinnier 70m would have been better)

- Rapping gear (harness, prusik, etc.); carrying this stuff also meant I could ask for a belay if I got really sketched out but still wanted to continue

- Climbing helmet

- Headlamp

- La Sportiva Boulder X approach shoes

- La Sportiva Mythos climbing shoes (wholly unnecessary, but I didn’t know that when I was packing the bag)

- Outdoor Research Verglas gaiters (for scree, mostly)

- Icebreaker Bodyfit 200 merino top

- REI Acme pants (original Schoeller Dryskin - I can’t stress enough how perfect these are for this type of activity)

- Patagonia Adze softshell jacket

- First Ascent synthetic puffy jacket

- Marmot Precip, just in case

- No-name light liner gloves, which got a little torn up

- Buff

- No-name winter hat

- Sawyer Squeeze water filter and bag (the little one - this made it impossible to care more than about a liter of water at a time, which made the pack a lot lighter)

- Pop Tarts, fig bars, and Chex Mix, i.e. high GI, low weight, no fat or fiber to slow down digestion (now’s no time for fat, protein, or complex carbs - just keep that blood sugar up!)

- Bear spray - being that I was imprudently alone for most of the day I thought it would be prudent to carry some along

- Trekking poles - they make moving over nontechnical terrain so much easier/faster

All this worked out to about a 15lb pack, which was ideal for this climb. I hardly knew the weight was there. I don’t think I’d change anything about this setup for future climbs unless I thought water would be less available, in which case I'd carry a 2L bladder or something. If I was willing to take a little more risk and lose a few style points I’d have ditched the rope, but there’s something disingenuous about rapping on someone else’s line if you didn’t carry one up yourself. And of course it's not impossible you'd get stuck having to downclimb instead of rap, which is fine when conditions are good but could be very exciting if they deteriorate while you're up above.

Can you do this?

The short answer is, "probably," but realize the risks you're taking. The way I see it there are a few things that allowed me to be successful on this climb.

- Physical fitness. If you can’t make it up the mountain at all, nothing else matters. And if you can't make it in a timely manner, you risk missing your weather window, or worse, getting caught up there after it closes. But it’s not like all you need to do is deliver your body to the top and then collapse - you need to have all your wits about you while you’re up there, and that means you can’t push too hard. Ed Viesturs talks about how the top of the mountain is really a “false summit” - the true summit of any climb is being back with your family and friends. Don’t push so hard that you only have enough gas to make it to the false summit; for most of us this means the more training the better. Mine was all done on flatland and I don't think I suffered much for it, although I wonder how much stronger I could have been if I did my hill climbs on something taller than 100ft.

- Technical skill and, more importantly, justified confidence. I’m not a particularly gifted climber, technically - I redpoint in the low 5.11s on sport and onsight (some) Devil’s Lake 5.8 on gear. But I’ve developed a sense (and I don’t think I’m unique in this) of when I’m absolutely secure and what would have to happen to make me fall at a given time. e.g. “If this hand pops off, I know I can recover from that - but if I lose a foot too it's game over.” This mental game is more important for this type of climbing than physicality alone - it let me move over the highly exposed sections of the climb without a second thought, because I knew that I was absolutely secure.

- Comfortability with the gear. This isn’t super crucial for safety or comfort compared to the other two points, but it can make a big difference in how the climb goes. I’ve spent a lot of time using the shoes, clothes, jackets, etc. listed above, and I know exactly what I have to wear to prevent overheating/freezing for a given combination of exertion, wind, and temperature. Using your gear well just removes one more obstacle to optimal physical performance while you’re on the mountain, and you’re safer from hypothermia if you’re not drenched in sweat.

- Knowledge and acceptance of the amount of objective risk inherent in this activity. You can do everything right on a route like this and still die. Your chances of dying are significantly higher if you decide to solo. You have to accept this if you're going to undertake activities like this without deceiving yourself. I said above that I was “absolutely secure”; what I meant was “as secure as I can be given the risk of rockfall and other objective hazards.” Even with perfect physical preparation and planning it’s always possible that a microwave-sized rock could squash my head and end my life or that an unexpected storm could roll in and trap me on the mountain. These are risks we don’t get to control, and everything we do in the mountains must be considered in this context. Soloing a climb (and climbing in general) isn’t something to take lightly, and I don’t. Awareness doesn’t diminish the risk, but I think it makes me more prudent and willing to turn around when conditions demand it.

- Luck. People as prepared and determined as I was get turned around by this mountain all the time. Sometimes things just don't go your way - but sometimes they do, and those are the days that keep us coming back to the mountains. Although I look back almost as fondly on the days that I didn't achieve whatever goal I had set for myself.

That's all, folks! Post your questions in the comments if you've got them! I'd love to hear feedback as well.

Comments

Post a Comment