|

|

Trip Report |

|---|---|

|

|

26.906°S / 68.57486°W |

|

|

Feb 8, 2023 |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Scrambling |

|

|

Summer |

Overview

As has become my annual habit, I went to South America in February and March of 2023 for 5 weeks of self-propelled, unsupported, and unresupplied climbing in the Puna de Atacama. However, unlike my previous Andes expeditions, this time I did not go alone. My friend Trefor saw some appeal in the style of adventure that I'd developed, and - as someone with a similarly high level of fitness and backcountry experience - I had no hesitation at all to have his company on this trip. Beyond that, it was just a whole lot of fun to have one of my closest friends out there with me. We're both recent PhD grads and multidisciplinary engineers, and we have never yet run out of things to chat about. Since returning, we've founded a startup together (in marine robotics, of all things) as a direct consequence of the conversations we had while wandering through the Atacama Desert.

Our expedition plan was ambitious, including up to 14 major 6000 m peaks over the course of five weeks of intensive cycling, hiking, and climbing. In the end, we did just five peaks and returned to civilization a week early. I'd still call this a respectable expedition given that we were traveling by bicycle with no outside support, but clearly there was a major disconnect between our plans and what we actually managed to do.

This trip report recounts the expedition, but it is also a bit of an analysis of why things went the way they did. It's taken me a while to understand both the reasons we fell short of our goals and the reasons why I thoroughly enjoyed this trip regardless. In the meantime I've done another solo expedition of comparable scope - and with a comparable success rate in relation to my plans. I think now I can dig into the reasons for the mismatch and my own path forward for future trips.

NOTE: Some of the picture captions got swapped during upload - I'll fix it someday, but if the caption makes no sense, that's why.

Planning

Trefor and I had discussed a variety of options for a long, self-propelled Andes trip:

- A series of 1-2 week forays into the High Andes around Mendoza and Santiago

- Climbing off-the-beaten-path peaks in the Puna de Atacama near Ojos del Salado

- A circuit of peaks around the Corona del Inca (incl. Bonete and Pissis)

- More technical climbs of a half-dozen peaks around La Paz in Bolivia

My main priorities were to do an epic expedition and hit some new peaks on the Andes 6000ers list. Trefor wanted most to journey into remote places. The concept that best aligned with these objectives was climbing in the southern Puna de Atacama - the same region as my 2022 trip, but to different locales and summits. I think it also made the trip more approachable; it's a pretty big leap to spend weeks cycling unguided in a country where you don't speak the language, but with this itinerary at least we'd be traveling on roads that I'd ridden before. We moved forward with this concept to prepare detailed plans.

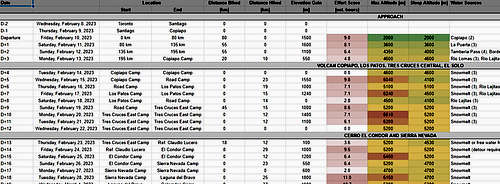

If you ask two engineering PhDs to plan a mountaineering expedition, it goes just about how you'd expect: a massive set of spreadsheets. We had day-by-day charts of camp locations, altitudes, and water sources. We derived an "effort" formula based on my past climbing experiences, and used it to gauge how difficult each day would be. We tabulated every gram of food we planned to bring, even to the point of (thank you, Trefor) determining which items were Pareto-optimal with respect to carbs and protein content. I obtained and reviewed a decade's worth of weather archives for the region to determine the probable amounts and patterns of precipitation. We tallied-up how much solar panel time it would take to charge our phones, satellite messenger, camera drone, and all the other little electronics we were going to bring. We data-mined Google Earth to compile an offline equivalent for the areas we'd travel. No proverbial rock was left un-turned.

We knew all this was overkill even as we made the plans, but it was fun to do it (fun for us, anyway). In hindsight, though, I think this level of planning was a key part of the reason our expedition didn't go as planned. By creating such detailed plans, we created for ourselves the illusion of control and predictability in a whole range of factors where we didn't have that level of control. We tabulated the perceived effort of each day based on distances and elevations, but in doing so we made an implicit assumption that the terrain we hiked and biked would be similar to what I'd encountered before. We built our itinerary on an assumed capacity to exert ourselves an recover, but recovery and initiative are dependent on more than just the work done and the time rested afterwards. We planned detailed diets that were nutritionally optimized, but theoretical optimality is little consolation if some of the staple food items become unpalatable after the 10th or 20th consecutive identical lunch. Spreadsheets are simple and clean, but reality can be messy.

As planned, the expedition would consist of four phases:

- One-off climbs of Volcan Copiapo and nearby Cerro Los Patos

- Ascents of Cerro El Solo and Nevado Tres Cruces Central from a common high camp

- A long out-and-back hike north of Laguna Verde to climb five summits up to 80 km off the highway

- A short peak-bagging foray into Argentina just south of Ojos del Salado

The Voyage South

We left Toronto on February 8 with an overnight direct flight to Santiago. As always, waking up to an eye-level view of Mercedario and Aconcagua was a great way to start the day. We boarded a short flight north to Copiapo after a brief stopover, and watched our bikes get loaded onto our plane a short while later. After collecting our bags at the Caldera airport, we arranged a shuttle bus ride into town - they charged us double because of the enormous bike boxes, but it was still a good deal less expensive than taxis.

Notwithstanding some run-down areas on the outskirts, Copiapo is a beautiful town full of greenery, quaint little shops, and friendly people. After checking in at our hotel, we had just enough time left in the day to stop by the hardware store for canister fuel and pick up a first load of groceries on the way back. We spent the evening assembling our bikes and organizing our supplies, then got a good night's sleep.

After breakfast at the hotel, we went out for a second round of groceries. We'd found pretty much everything as planned, and we even grabbed some fresh fruit for the road - a bit of extra weight and not very mass-efficient, but definitely a good morale-booster while it lasted. We spent the rest of the morning getting our kit sorted and packed. Each bike had four 20 L panniers entirely filled with food and water, enough for 5 weeks at 4500 calories per day. Our sleeping bags and sleeping pads - bulky but not heavy - were strapped to the front racks. All the rest of our camping and climbing gear was packed in backpacks tied down across the rear panniers. The hotel graciously agreed to store our bike boxes and carry-on bags until we returned.

On the Road

We left the hotel in Copiapo at 13:30 on Feb. 10. After navigating the town's surprisingly good bike routes along the start of C-31, we headed north against a stiff headwind. The deep desert valleys throughout the region tend to funnel the prevailing winds along their length so you're almost always riding either with the wind or directly into it, and even a small change in the angle or shape of the valley can change the local air currents. I knew from experience that we'd see downwind riding where C-31 turns east into the deep desert, about 25 km outside of town. When we stopped for a snack break, Trefor asked me how much farther we had to go before we'd reach the turn. I sinply smiled and gestured down to the giant white arrow painted at our feet - we were already in the turning lane with about 100 m to go!

While Trefor and I are similarly fit overall, I am first and foremost a cyclist - I am well accustomed to bouts of hard riding, and generally won't wear myself out even when the going gets tough. Trefor is more of an athletic generalist, and this stretch turned out to be a challenge with our massive, bulky bikes catching a lot of drag against the wind. Within a couple of hours from setting out we made it to the turning point where we would head downwind, but that first 25 km had cost us more than we anticipated. We cruised along C-31 for a further 35 km and stopped for a late lunch. However, my pace through the earlier upwind stretch had been a bit more than Trefor was accustomed to, and we decided to stop at that point for a night's rest.

We set out again in the mid-morning on the 11th and rode about 20 km in the first hour to reach the bottom of the first big climb. We'd already come up 1200 m from Copiapo (500 m above sea level), and over the next hour and a half we pushed our bikes up an additional 400 m through the steep valley to reach a critical milestone: the first water source. At the top of the valley, the groundwater is forced to the surface and flows vigorously through a few small waterfalls. It's very "hard" water with a high mineral content, but clean and cool. As Trefor was still feeling the effects of the previous day's ride, we elected to camp at this spot for the day - it's the only prepared site I know of along the entire route, and the lush greenery is a stark contrast in a region of mostly bare rock and sand. We spent a while exploring the surrounding cliffs and gullies, but got to bed early in anticipation of a long third day.

In the morning, we proceeded northeast along C-31 with the help of the typical tailwind. There were a handful of grassy settlements (goat farms, primarily) for the next 5 km while the water was still near the surface, and then abruptly nothing - we rounded a bend and there was no more green. Pushing onwards at a steady pace, we were both feeling fit and rested now. We stopped for lunch within sight of the 3000 m altitude marker, and gained a further 800 m in the afternoon over a distance of 58 km for the day. Our stopping point was at the base of the last steep uphill climb - we knew what we'd be doing tomorrow.

The morning of the 13th saw us once again on foot pushing our bikes up the road. The steady slope exceeded 15% in places, and some of the switchback turns were much steeper still. It took us about 2.5 hours to ascend the 500 vertical meters from our camp to the pass at 4340 m. While the temperature was quite moderate, the sunlight was intense - plenty of sunscreen used that morning. From the top of the pass we could see both Nevado Tres Cruces and Volcan Copiapo. Both were covered in snow, and we surmised that there had been a recent fall. We coasted down the far side of the pass over the next hour, and made a brief stop at the Chilean border control outpost to show our expedition permit and refill our water bottles. 10 km past this point, we left the paved highway and proceeded along a dirt road that would lead us towards C-601 and Volcan Copiapo, our first climbing objective. We thought we'd reach our base camp that day, but the cross-road to C-601 proved to be in much worse shape than we'd anticipated: the road was a washboard through sandy gravel. I took the lead - due to my bike's marginally wider tires, I could tolerate a slightly softer road surface without bogging-down. Trefor could then have some foreknowledge of where the soft spots would be. Regardless, we both spent a lot of time on foot dragging our loaded bikes through the sand. We did about 15 km of this before sundown, and pitched our tents on the side of the road.

We dragged our bikes through nine more kilometers of sandy washboard road in the morning, expecting to reach C-601 and a much firmer road surface. Much to our dismay, the "real" road was in little better shape. We continued a mix of riding and pushing, but soon came to the conclusion that we should stash our bikes sooner rather than later and continue on foot. In the mid-afternoon, we stopped to scout route options with my drone - being able to see from a vantage as much as 500 m up and several km away is a huge asset. We quickly found a backcountry trail not far ahead, as well as confirming that there were reliable water sources in the vicinity. After a few km more riding, we stowed the bikes in a gravel pit and continued on foot with about a week's worth of supplies. We set up camp at sundown about 13 km due north of Volcan Copiapo. Our camp was next to a marsh, and we watched some flamingos wading in the distance as we built our tents and cooked our dinners. A fox yipped in our general direction for a while from farther down the trail. Five days in, and we were already almost two days behind our schedule - an early indication of how this trip was going to go.

Copiapo and Los Patos

Our revised plan for the first two objectives was to trace an enormous triangle from our bikes to Volcan Copiapo to Cerro Los Patos and then back to our bikes. On Feb. 15, we started the day at 4080 m about 3.5 km past our bikes and hiked up the valley towards the north flank of Volcan Copiapo. Trefor had brought a small set of binoculars, and we were able to identify a likely high camp on the slopes far ahead at an altitude of about 5000 m. We wandered up a system of sandy gullies, sometimes following jeep tracks but more often finding our own path. Eventually, we emerged from the slope onto the broad bench of gravel and lava rocks that we had seen earlier. We found a near-perfect campsight among some larger rocks - protected from the wind, an excellent view of the larger peaks to the north and east, and well-positioned for our summit bid in the morning. I introduced Trefor to the art of harvesting and melting snow penitentes for water, and we rested through the afternoon.

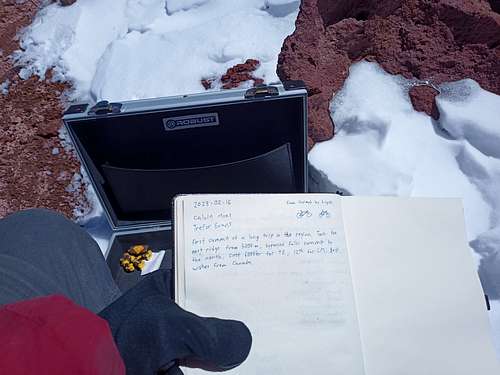

The sky was clear in the morning, and we set out for our first summit around 07:30. We made a short traverse around the mountain to the rockier east ridge. Trefor opted for a line up a broad gully, while I liked the more scrambly look of the adjacent rock ridge itself. We climbed parallel lines roughly 100 m apart, reconnecting just below the prominent snowfield at 5450 m where we stopped for a snack while I did some videography with my drone. From there, it was easy scrambling and steep hiking up the slope as we traversed around the north side of the false summit. We post-holed through shin-deep snow for the final 100 m up to the true summit, reaching it just before noon under scattered light clouds. After signing the summit book and flying the drone for a while, we had a snack break sitting on a centuries-old platform built by Inca climbers. The descent was smooth and easy - a prominent scree gulley led us almost directly back to our camp. As we got there, an evening storm rolled in and started dusting the upper slopes with snow.

We awoke within a fog to about 1 cm of snow on the ground. The fog soon cleared, and by 9:30 the snow was entirely melted to leave the familiar dry desert ground. We broke camp soon after and traversed at 5000 m back to the base of the east ridge before heading down-slope on a line directly towards Cerro Los Patos, our next climb. The rest of the morning was spent wandering down the hills and gulleys below the mountain. We reached the bottom of the valley in the early afternoon, and hiked for some time along (and at times, through) another large marsh beside the backcountry road C-347. We easily found the jeep trail beside the dry streambed of Rio Lajitas - for once, the terrain was easier than expected. We kept hiking until after sunset to reach 4400 m - not as high of a camp as our original plan called for, but sheltered, scenic, and with flowing water now in the adjacent stream. We rested for a day, again receiving a light overnight snow which melted by mid-morning. Scattered clouds shrouded the mountain and gave it an ominous and mysterious look when I reconoitered the terrain with the drone.

On Feb. 19, we headed for the summit. We were away from our camp under clearing skies just as the sun crept over the horizon. Another round of snow left the valley and the mountain ahead blanketed in white. We made decent time finishing the approach, doing 10 km and 800 m of vertical gain in a bit less than 4 hours. That said, it took us until past 11:00 to reach our planned high-camp location. Even by my very loose scheduling standards, that's a late start for a summit attempt. We still had 1000 m of mountain to climb, and then a long hike back to our base camp.

As we hiked up, we more or less kept pace with the receding snow-line. Surveying the wide, gentle southwest face, we chose a rockier line up towards the subsidiary summit - not a very efficient route to the main peak, but we hoped that by scrambling on the rocks we could avoid some of the loose powder snow that was by then already coating our shoes and chilling our feet. As we plodded up the face, wisps of cloud gathered in the east as a light breeze blew at our backs. Snow-crusted shoes notwithstanding, it was a fairly comfortable ascent up to the col under bright sun and clear skies.

As we started up towards the main summit (400 m vertical to go), the weather finally started to turn. The wind at our back gradually grew more forceful. Clouds materialized around the peak, blocking the wamth of the sun even though we could see it was still clear and sunny as close by as the lower summit. We chatted briefly about whether to continue - we were feeling good with the altitude, but our clothing and footwear was marginal for the conditions we now faced. With barely half an hour of climbing left to reach the top, we continued upwards.

The summit of Los Patos is gentle and broad - even once we got up there, it took us nearly 15 minutes in the howling wind and whipping clouds to find the actual highest point and its small cairn. I pulled out my phone to snap a couple quick photos, deeply chilling my hands in the 15 seconds that task required. We wasted no time loitering at the summit, but immediately turned around to follow our rapidly-filling footprints back the way we came. I stuffed my hands deep in my jacket pockets to regain some wamth. A few moments later, I stumbled on a loose boulder just as an exceptionally fiece gust blew by. With my hands otherwise occupied, I fell over hard - Trefor even heard my knees hit the rocks over the noise of the wind. For first few moments, I thought I'd messed up bad. A break or a bad sprain out here wouldn't be lethal, but we'd have had our work cut out for us getting down and it'd certainly be the end of the expedition. As the inital flair of pain subsided, I tested my knees to find that they were bruised and sore, but possibly no worse than that. Easing myself to my feet, I casually suggested that it was time we be elsewhere.

We made our way carefully back down to the col against the now-headwind, eventually finding a bit of shelter behind a ridge where we stopped for a bit of rest and a snack. I was finally coming down off the adrenaline rush of a close call, and concluded that I hadn't done any lasting damage. Still, I was more careful than usual picking my foot placements on the long descent. We stopped for another snack break at the bottom of the main slope. From there, it was just a long walk back to the camp - all told, a 14 hour day.

After sleeping-in and relaxing for the morning, we packed up our camp and walked out the way we'd come. We turned north at the road, and reached our bikes shortly before sundown. The gravel pit provided a reasonable level of shelter from the wind, and we camped there for the night.

El Solo

Our plan the next morning (Feb. 21) was to move camp all the way up onto the high plateau, on the far side of the Tres Cruces massif. It would have been a solid day's effort on good terrain, but instead we were faced with 12 km of washboard road through sandy gravel, then a somewhat sandier 8 km of off-road jeep track before even getting to the real road distance and elevation gain. We were both thoroughly unenthused by the prospect of pushing the bikes through more sand, even though this would be the shortest route back to good-quality roads. There wasn't much option at this point.

By lunch time, we had only just reached the off-road trail - we more or less dropped our bikes where we were and made our usual lunchtime soups, then Trefor napped in the sun while I read a book under some improvised shade. It was clear that we weren't going to get to the planned camp between Tres Cruces Central and Cerro El Solo. Instead, we set our sights on just reaching the scenic and sheltered Rio Lamas before day's end. We made steady progress over the sandy ground, occasionally even riding for a few meters at a time. Upon reaching the river, we decided that we could really use a proper rest day, and it might as well be here where the altitude was still moderate and the water ran clean and clear.

The morning of Feb. 22nd was the first really clear day we'd had in a while, almost cloudless from sunrise to sunset. The splashing stream and overnight chill had encrusted the riverside grass with ice, and the previous days' fresh powder on Tres Cruces made for intense contrast between light and shadow as the sun crept over the mountains. I spent much of the morning flying the drone up and down the valley for some excellent imagery of the river, desert, and snow-covered mountains.

We spent the day reading, resting, and doing some much-needed laundry - it takes no time at all to dry things when the sun is out in the Atacama. As a bit of a culinary experiment, I tried making falafel out of some veggie burger patty mix that I'd grabbed on impulse in Copiapo. It took a bit of trial and error, but eventually I managed to get my Jetboil stove set up as a deep-fryer and produced a steady stream of passable falafel until we were both full. We went exploring in the afternoon, leisurely wandering down the canyon and scrambling through the crumbing cliffs. One side-canyon in particular was particularly deep and narrow, so we climbed out through it before hiking back to camp.

We were on the road around 11:00 the next morning. After a short stint pushing our bikes up a steep section of the paved highway, we were finally back on two wheels for about 25 km of steady riding. Our plans for this next part were a bit nebulous - we thought we'd see what the terrain looked like and decide an exact route when we got there. We saw an old bulldozed trail leading off the road into the gap between Tres Cruces and Barrancas Blancas, so after stopping for luch we stuffed our bikes in a culvert under the highway and continued south towards Cerro El Solo on foot. A couple of hours of hiking brought us to the edge of one of the most interesting landforms in the area: permafrost gullies. I had initially assumed this to be sand - it certainly looks that way in the satellite imagery - but the true nature of this terrain was immediately apparent as we started hiking up through one of the larger ravines. Under a thin scrim of dry, sandy pumice, the ground was saturated with ice. As the sun dropped behind the Tres Cruces peaks now to our west, the temperature plummeted and we started looking for a spot to camp. The gulley we were in led us up to the surface at about 5200 m, and we figured this was as good a spot as any for a base camp.

We pitched our tents in a shallow depression for a little shelter from the evening breeze. It was a clear, cold, and windy night, and we were essentially sleeping on ice. Add to that that we had come up almost 1200 vertical meters from the previous camp, and it was no surprise that this was one of the least enjoyable nights on the trip. The wind died around midnight. When I got up in the small hours of the morning to "answer the call", it was tolerable to be out of my tent in a t-shirt. The off-white pumice sand glowed in the moonlight - no need for a headlamp that night!

Overnight conditions notwithstanding, the morning was again clear and calm. We set out for the summit of El Solo shortly after sunrise. Within 50 m of leaving our camp, the tents were hidden among the near-identical gulleys that cover the area. I hurriedly set up a flag on one of my trekking poles and jammed it among some larger chunks of pumice to mark the location. A short while later, we came to the abrupt edge of one of the two much larger gulleys in our path. Almost perfectly triangular in cross-section, this one looked every bit of the 50 m depth our topographic maps indicated. We hiked along the edge towards Tres Cruces to find a more gentle way down, and then delicately ascended to loose pumice-sand slope of the far side. Continuing southwest, we largely bypassed the second major gully - where we crossed, it was shallow, wide, and filled with penitentes.

Having reached the base of El Solo itself, we espied our route up to the top, mostly just a slog up a featureless slope of pumice scree. Trefor was fatigued from the altitude, cold, and poor night's sleep, and he decided he didn't need to bag this summit - I was going solo to the top of El Solo. We briefly conferred about rendezvous and timeline plans, and then I headed up-slope at a comfortably brisk pace. The forecast indicated that there would be strong wind through the afternoon but sunny and not particularly cold, and the weather did not disappoint. I reached the summit almost exactly at 14:00 under a cloudless sky, leaning into what must have been 60-70 km/h of sustained wind roaring over the mountain. I knelt briefly by the remanants of a summit cairn, rebuilding it a bit with a few larger stones and leaving several Canadian nickels and dimes as a distinctive token of my passage. It wasn't a great setting for leisure, so I quickly headed down - not quite the way I'd come up, but curving around the maountain so that it shielded me from the worst of the wind for much of my descent.

When I reached the bottom about an hour later, nothing looked familiar. I was a little ahead of when I told Trefor to expect me back, but I couldn't figure out where we'd agreed to meet - short of hiking a couple hundred vertical meters back up to where we discussed it, I had no precise notion of where I needed to be. Figuring we'd be visible to each other on the open expanse north of the mountain, I set off in the general direction of where I thought we'd agreed to meet. As it turned out, I'd ended up a fair bit east of our outbound track, and the gulley I followed now was not the one we'd pointed out when parting ways. I hiked along for perhaps 30 minutes before I noticed Trefor following far behind - he'd seen me in the distance as I passed east of where he'd relaxed for the afternoon.

We continued along until we reached the first major gulley, where our crossing was now slightly more difficult because I'd inadvertently led us to a steeper, deeper section. Heading back to the northwest to regain our previous path, we attempted to reach a similar point as in the morning for crossing the remaining large gulley. We descended within sight of where we'd come through before, but this time just far enough up the ravine that we noticed a large cleft in the edge where two tributaries merged. Upon closer inspection, we discovered an unexpectedly large ice cavern where wind and runoff had melted through what I assume to be either a sand-covered snowfield or else a remnant of the much larger glaciers that covered this area in centuries long past. We spent a few minutes exploring and photographing the fantastical icicles and scalloped ceiling of the interior, noting the thick covering of dust on the floor that we took to indicate that this cave was a lasting feature.

The flag I'd set up proved helpful in relocating our camp, and besides that it was a fun little splash of warm colour against the blues and greys of the surrounding environment. We went to sleep shorlty after sunset, but it was another cold and windy night. In the morning we discussed our options. The original plan had been to climb Tres Cruces Central from here, essentially making up a new route on the (probably) non-technical but steep and rocky east face. The forecast called for another couple of days of high wind, and we decided that this summit was best left for another time. Between the less-than-stellar camp environs and the prospect of doing a long scramble while blasted by intense wind, neither of us felt great about going for the peak.

We hiked back down to the road, stopping at the last penitente field to grab a goodly chunk of hard snow each. After melting our ice to refill most of our bottles back at the bikes, we continued riding east along the highway. I honestly don't recall where this day went - the distance we hiked was downhill and not more than 15 km, but by the time we'd melted our ice, eaten a late lunch, and packed our bikes to ride, it was already after 19:00. Whatever the reason, we ended up riding the last 10 km of our 30 km road distance in complete darkness, thankful for the near-total absence of any other vehicular traffic.

We arrived at the Refugio Laguna Verde long after most of the dozens of other climbers camped there had gone to sleep. We set up our sleeping mats on the floor inside the small hut. Trefor went straight to sleep after a quick dinner, while I elected to avail myself of the indoor hot spring that filled a stone-lined tub roughly 2 meters square at the back of the Refugio. Owing to the late hour, I had the hot spring to myself. It was just large enough to stretch out and float. My thermal camera showed a water temperature of 34 degrees Celcius, and I sat comfortably in the tub to eat my dinner and read my ebook for more than an hour before finally drying off and crawing into bed. I wish I'd taken some pictures, but relaxing in a warm bath had occupied my mind to the exclusion of all else.

Cerro El Condor

The morning revealed the hectic and crowded reality of the refugio. With at least a dozen commercially-guided expeditions having set up their base camps here, there was competition for everything - kitchen space, hot spring access, even a lineup for the outhouse. Trefor and I quickly concluded that the scenery and slight convenience of the hut wasn't worth staying another night, so we packed up our gear and half-rode, half-pushed our bikes back up the road and around the the western edge of Laguna Verde. We found a spot far off the road below the cliff edge where our bikes and gear would hopefully be out of sight from passers-by, and we kitted-up for what was expected to be the most arduous phase of our expedition.

Somehow, we'd imagined that we'd be able to do 25-40 km daily on foot through trackless terrain which we ought to have known was mostly sand. We thought we'd do this kind of distance every day for more than a week, except on the days when we were climbing one or multiple summits. It seems obvious in retrospect, but this wasn't remotely feasible in the way that we envisioned it.

We left our bikes around noon intending to reach a prospective campsite at the base of Cerro El Condor before sunset - just a 25 km uphill walk... 4500 m above sea level.. with 30 kg packs... through loose sand. By sundown, we had only done 14 km. We hastily set up camp in the lee of some low boulders (I lost my second Iron Ring in the sand while setting up my tent) and took stock of our water. We'd both packed on the assumption of reaching the icy slopes of El Condor by day's end, and we had enough only for a lean dinner, a bit to drink with breakfast, and half a bottle for the trail the next day.

Thankful for another clear and calm morning, we packed up our tents and made steady progress towards El Condor. I noted on my GPS app when we'd crossed the international border, but nothing else indicated a change - no marker or signpost, no deviation in the Jeep track we were roughly following, no angry border police chasing us from either side. We left the trail where it turned through a broad ravine towards Laguna Escondido, heading east towards the mountain. As we scrambled up and over the ravine edge, we finally reached the edge of the lava fields.

Most of the volcanoes in this region are significantly weathered, with surface material ranging from a few hundred thousand years old to tens of millions. As well, a lot of the other mountains are substantially composed of softer rocks like pumice that crumble into sand rather quickly. Not so with El Condor! This volcano's last major eruption was perhaps 20,000 years ago, and the blocky, solid lava still looks like it just cooled yesterday. Much of the mountain is heaped with pieces generally 15-30 cm across, bunched up in waves tens of meters tall. Nowhere is it meaningfully settled or filled-in by wind-blown sand - the desert ends, and the lava begins.

We found a sheltered camp on the margins of the lava field with some flat ground and an ice seep to melt for drinking water. As we'd split the approach into two days, we figured we'd go for the summit in the morning.

With another clear sunrise, we anticipated that this would be a fun day out. Only 14 km round trip and 1200 vertical meters - should be back at camp for a late lunch!

Three hours into the hike has us barely 3 km into the lava fields, and we'd only gained about 200 m of altitude. On every third or fourth step the lava blocks shifted beneath our feet, and we'd both had numerous minor falls on the unstable terrain. As much as I'd wanted to put up an interesting "new" route in a region where routes are usually trivial, this path was just not working out. We did some quick scouting with the drone to both find an efficient path back to camp and to evaluate alternate routes for a revised summit attempt. It still took more than two hours just to reach the tents.

We took the afternoon and following day to rest and consider options (for this climb and for the trip overall). The prospect of hiking to the more northerly summits no longer seemed realistic. Carrying heavy loads on foot through sand would be difficult enough, but also we would have to make unprecedented daily distances to get from each water source to the next - either that or add multiple days worth of water to our already unmanageable loads. We settled on summiting El Condor before heading back to the bikes.

After a rest day, we tried a new approach to route-finding for this mountain: avoid the lava fields. Between our satellite imagery and drone reconnaissance, we were able to scout a route that - although much longer overall - only required crossing about 300 m of loose lava rather than the 6+ km of our original line. It would still be a long day, but much more manageable and with a far lower risk of mishap.

We set out just after sunrise walking east along the border of the main lava field. After about 4.5 km of hiking on mostly level ground, we reached our crossing point - a narrow strip directly south of the summit where one of the recent eruptions down the east flank of the mountain had flowed over to the west side. After scrambling up about 20 vertical meters of steep lava-block embankment, we carefully scrambled across the flow and down the other side onto smoother terrain. We then followed a prominent and largely snow-covered gulley to the base of the main slope. After a snack break at 5800 m, we continued up the mountain via a steep, snow-filled gulley. We exited the gulley to the west at about 6000 m, and from there it was a steep but straightforward hike up to the crater rim.

While still a short distance below the summit, I was surprised to see steam billowing out of the ground ahead of us. None of the (admittedly sparse) accounts I'd read of this mountain reported any geothermal activity, so this was entirely unexpected. By chance, our south-to-north line had taken us directly through the main area of these vents. Using my phone's built-in thermal camera, I measured a few of the larger vents at roughly 80 C - about as hot as water can be at this elevation. It wasn't a particularly cold day, but we welcomed the opportunity to sit in the steam and the ambient heat radiating up from the ground. We spent perhaps 10 minutes here before continuing up. Although the main group of vents was 10-20 m below the rim on the south side of the caldera, we found several more as we traversed the rim to the summit cairn on its northwest edge.

Despite some developing cloud cover, we spent a good while on the summit. We wrote a page in the summit book, being sure to congratulate Argentina on their World Cup victory. I flew my drone around the summit to get some good images for an eventual SummitPost page - not the best shots I've taken on account of the clouds and my hesitancy to send the drone out really far for a better perspective, but still probably the best images anyone has of the top of this mountain.

We descended the way we came - a relatively uneventful, if lengthy, affair. We crossed the lava flow again just before sunset, and it was almost fully dark when we returned to our camp. It had taken us a bit over 14 hours round-trip. We took the next day (March 3) as a rest day. I tried to catch the evening light for some interesting drone shots of the west side of the mountain, but it didn't really turn out - maybe my exposure settings weren't great, or maybe I just waited too long before trying.

We hiked back to our bikes on March 4, which took almost 6 hours not including several breaks. Arriving at the bikes shorlty before sunset, we set up camp on the bluffs overlooking the west end of Laguna Verde. We restocked our water from the stream draining into the Laguna - some careful straining and a generous application of water purification tablets was warranted on account of the high concentration of fly larvae. It was a beautiful spot to camp in the moonlight. Although I was disappointed that we'd cut short this major phase of our expedition, I knew that neither of us had the energy or motivation to have gone further out to the more distant peaks.

In the morning, we biked back west along the highway. We discussed whether we would still try any of the peaks south of Ojos del Salado. We both agreed that we probably could manage it, but Trefor was starting to lose interest in peak-bagging for its own sake and I was not thrilled with the prospect of another long, uphill trek with heavy packs. We decided on a compromise: we'd stop at Tres Cruces for a night or two and have a go at the Central peak, the only one of that group I had yet to climb.

Tres Cruces - Round 2

Upon reaching the trailhead for the standard camps on the west side of Tres Cruces, we once more ditched our bikes in a culvert under the highway and packed up our bags to hike up to a suitable camp. I knew of two established camps: a base camp at 5100 m, and a high camp between the Central and Sur peaks at 5950 m. On the approach, I suggested to Trefor that we could pursue different objectives for the following day. I could tick another box on my list by summiting the Central peak, while he might have a more casual and scenic day trying the Norte peak with its lower altitude and stunning blue pond. Considering this plan, we decided to find a campsite between the two established sites (the low camp would mean a very long day for me, while the high camp would oblige Trefor to descend several hundred meters before heading towards the Norte summit. We found a good spot in the lee of a large snowfield at 5370 m and set up our tents in the light of one of the trip's best sunsets.

I woke at 06:30 to eat a quick breakfast and assemble my usual summit-day kit: drone bag, water bottle, InReach, first aid kit, and a few granola bars. I set out from the tents at 07:00. It was a clear and cold morning in the shade of the mountains, so I climbed hard to warm myself up a bit. As I made my way up the gulley towards the col, I passed by the tent pad I'd carved out when I climbed the Norte and Sur peaks in 2022 - it was one year to the day since I ascended the Norte summit. I took a few pictures of the shadow of Tres Cruces stretching to the western horizon. It's not quite the epic effect of Pico de Orizaba in Mexico, but still a scenic view.

After reaching the col at 09:15, I settled into a more casual pace and continued on an unplanned line up the southwest aspect of the peak. The wind was generally calm all morning, and I took a snack break on a broad bench at 6270 m. As I had expected this to be an easy scramble, I was surprised to find a tall and steep slope of sun-hardened snow on the final stretch to the summit. At about a 45 degree angle for 50-60 vertical meters, this slope was nothing notable from a mountaineering standpoint; in crampons, I'd not even pause. That said, I was wearing hiking shoes and microspikes. While it looked like there might be easier terrain if I hiked around to find a different line, I was in the mood for a bit of a challenge - I headed straight up on a direct path to the summit. Stepping delicately in my microspikes and using my axe in the high-dagger grip, I spent about 15 minutes working my way up the slope. As I reached the summit area, the slope leveled off into a soft snowfield about 50 m wide.

I located the summit cairn on the far ridge of the caldera, happy to see it marked with a Canadian flag sticker by the expedition that installed it decades ago. Despite a clear sky, the wind had picked up too much for a drone flight to be feasible, so I contented myself with writing a page in the summit notebook and pausing for a snack break. It was 12:05; I'd done twice the usual elevation gain for a summit bid, and according to the trip times scrawled in the summit book I'd taken hours less than typical to do it. Fitness and acclimitization will get you far!

I descended at a comfortable pace, reaching the col by 14:00. I briefly considered running up the Sur peak for old times' sake, but that would have kept me out well past when I told Trefor to expect me back. I took a few final pictures then continued down the scree slope back to camp. I reached the tents at 15:00 and made myself a late lunch.

Having done the Norte climb from a similar camp in similar conditions, I expected that Trefor would beat me back to camp despite my earlier start. However, he wasn't there when I got back. I relaxed in my tent for an hour, and then a second hour - still no Trefor. I started to think through possible scenarios for getting over to the Norte peak and looking for him - maybe he'd lost his way or sprained an ankle. By 17:00 I decided to set out so that at least I'd be able to get there and look around before sunset. Just as I came out of my tent and started to kit-up, Trefor arrived over the snowfield beside our camp; he had gotten a bit lost wandering around the far side of the Norte caldera but was none the worse for wear. As there was still enough daylight to reach our bikes, we wasted no time in packing up our tents. We reached the bikes at sundown and resolved to get an early start to the ride back to Copiapo in the morning.

March 7 was one of the coldest mornings of the trip despite being back down to only 4300 m. By the time we'd packed our tents and loaded our bikes, we'd both chilled our hands pretty intensely. We rode for a few km, but soon had to stop to warm up - we could barely squeeze the brakes on our bikes. The situation improved considerably once the sun crept over the Tres Cruces massif, and the day became much more comfortable. We coasted down the highway beside Rio Lamas, not even stopping for pictures. We cruised steadily across the open ground to the border outpost. Trefor knew as well as I did that the late morning would bring a headwind or crosswind that would make this stretch considerably harder - we wanted to make sure we'd get through and be able to make a lot more distance later in the day.

We reached the border outpost by 11:00, refilling just a couple of water bottles each to have enough for the day. As the wind had not yet picked up, we were able to ride up the first few km of gradual slope towards the 4350 m pass overlooking the Salar de Maricunga, the last uphill we'd need to do on the way back to Copiapo. I had originally hoped only to make it over the pass and down the other side that day, but we were making great time; we reached the top at 15:30 and coasted down the far side. We stopped briefly to wander around the otherworldy landscape below an old mine where acidic groundwater had leached minerals up to the surface, which then crystallized into a convoluted and multicoloured crust. The wind had strengthened as the day wore on, and we were now facing a 30+ km/h headwind.

Alone, I probably would have set up camp and continued in the morning. However, with two riders we were able to take turns alternately breaking through the headwind and drafting behind. Despite a consistent 2-3% downhill grade, being out in front was often hard work. Regardless, we made steady progress to cover another 55 km that day. We reached the grotto above La Puerta just as the sun dipped below the hills. We'd come down almost 2.5 km in altitude since the morning. The warmth was pleasant, but we could also acutely perceive the thicker, denser air - it felt just a little bit harder than it should to inhale that evening.

I took a much-needed shower in the waterfall beside to grotto. The water wasn't warm, but I didn't mind at all since the environment was otherwise dry and comfortable. It was nice to be clean! We set up our tents and set our alarms for one last early start to beat the next day's wind back to Copiapo. Although we were up in good time, the wind came on a bit earlier than usual. I still felt that I had some energy to burn, so I got out in front and pushed hard through the last 25 km into town.

Back in Civilization

One thing I've found about myself on these trips is that I genuinely don't mind the repetitive food. As long as I've got decent nutrition and flavour, I'm okay to eat the same thing over and over again. Trefor didn't share this perspective, and had greatly missed fresh fruit, fresh bread, meat, and all the other culinary trappings of modern civilization. With this keenly in mind, we stopped for lunch at the first grocery store we passed. While I waited with the bikes, Trefor went in and got us a broad selection of simple, good food: nectarines, bananas, fresh bread, cold cuts, cheese, yogurt, and a liter of orange juice for each of us. We spent a leisurely hour enjoying this simple fare before eventually wandering over to Hotel Portal del Norte (a small outfit with minimal online presence but nevertheless inexpensive and excellent in all respects). After showers and a healthy dose of WiFi, we went back out to a small pizza shop on the town square for another large meal.

In the morning, we made some open-ended plans to go and camp on the coast for the last few days of the trip. The regional museum happened to be open, so we wandered through the various cultural, ecological, and mining exhibits - particularly cool to see the original note from the miners rescued near there in 2010. We left for the coast the following morning, March 10. After some brief negotiations with the bus driver, we were able to put our bikes and backpacks in the luggage compartment of the coach bus for the hour-long ride out to the seaside community of Caldera. We found a grocery store in this sleepy little town as well as picking up a couple of beach towls at a tourist shack near the waterfront.

Not wanting to deal with crowds or campgrounds, we had picked a spot some distance south of town to look for a place to camp - a rocky point called Punta Huber, just up the coast from a rural beach called Playa Chorillos. We took our time on the ride out to our chosen spot, stopping in the (apparently quite popular) town of Bahia Inglesa to swim at the public beach and grab some cold drinks.

The ride south from there was perhaps the most desert-ish terrain I've biked through. The route along C-31 into the Puna de Atacama is definitely dry and legitimately a desert, but there I mostly notice the hills and ravines more than the dryness itself. Biking south along this stretch of the coast, it's just open, sandy terrain dotted with cacti - a stereotypical desert.

We arrived at the beach in the late afternoon and wandered some distance off the normal trails to find a mostly-concealed campsite among the many wind-sculpted sandstone pillars scattered across the shore. The water itself was at the base of a short and broken cliff about 100 m away from our tents. We mostly had the place to ourselves - aside from the occasional locals visiting the beach (far out of sight from our camp) and one time a car driving through on an offroad trail, we didn't see much of other people.

We spent a few days and nights here, mostly just relaxing. We did a bit of swimming (Trefor more so that me), although the water was quite cold on account of the Humboldt current flowing up from the southern ocean. I spent long hours wandering among the tide pools to observe a wide variety of kelp, fish, invertibrates, and seabirds. On the second day, I even managed to spear a few large crabs with my trekking pole (shoeless and shirtless a la Tom Hanks), which I then steamed in my Jetboil and ate with Chilean pebré sauce ("You gotta love crab!"). I also spent plenty of time relaxing in the shade, reading books on my e-reader, and casually hiking up and down the coastline - nothing to do and nowhere to be, just on vacation. It wans't what I'd planned to be doing when we set out, but not at all a bad way to spend some time.

We headed back to Copiapo on March 14, again stopping to swim at Bahia Inglesa. Our flight back to Santiago wasn't scheduled until the 16th, and that turned out to be a very good thing: the hotel where we'd left our bike boxes had discarded them some days prior on the assumption that we were never coming back. I'll admit my Spanish is not great, but I definitely said "el quince de marzo" while pointing at the corresponding square on a calendar. This was also the third trip I'd done setting out from this particular hotel, and I'd always come back for my bike box before. Anyway, we were annoyed but still had time to go out to all the local bike shops and find replacement boxes. It took a morning of wandering around town and explaining our situation, but in the end we found what we needed freely available from a sports store in the mall. By the evening, we had fully disassembled and packed our bikes as well as all the rest of our bags for the flights back to Canada.

I had previously hired a taxi each time to get to and from the airport (roughly 30,000 CLP or $45 CAD), but this time we decided to try taking the bus (2,200 CLP or $3.30 CAD). It was easy enough to load up our bike boxes and bags, but we were in for a bit of a surprise: the bus stop for the airport is literally the side of the highway, leaving us with a walk up and over an overpass and then a further 500 m to the terminal itself. This wasn't insurmountable, but certainly built up a sweat since we each had a bike box (25 kg), a large bag (20 kg), and a well-stuffed carry-on (5 kg). My shoulders were appropriately sore by the time we'd got inside (sunburn from the beach didn't help). The flight south to Santiago was uneventful, and after a few hours' layover we were on our way home.

Reflection

This trip was fun, and climbing 5 major summits in this style isn't bad for 4 weeks on the road. That said, it certainly was not what I expected. We left 8 planned major summits un-attempted (and a few minor ones as well) and took a lot more time than I'd thought traveling between objectives. So... why? Why did we fall short of our goals, and why was it still fun?

I think the reasons I enjoyed the expedition despite the challenges were 1) that I genuinely love that grand and desolate environment as well as the experience of being there, 2) I got to share the experience with one of my oldest friends, and 3) each time our plans changed, I made a deliberate choice to see it in a positive light.

There's something about the Puna de Atacama that really resonates with me. It definitely has to do with the remoteness and isolation - it's a place where you can hike up the tallest hill and (except for maybe the occasional road in the distance) still see no immediate evidence of modern civilization. There's nothing wrong with cities and buildings, but I like that there are places one can go that are still wilderness. I also enjoy the climate and altitude. The cold, wind, blazing sun, and thin air are constant reminder that you're a lot closer to the edge of survivability, and at the same time these factors combined with the geography make the Puna de Atacama seem almost alien. It's like what Mars could look like when the terraforming is halfway done!

I love to share the things I enjoy: recommending my favorite books and movies, cooking great meals for my friends and family, and even recruiting new participants into the various adventure sports I have tried. My previous expeditions in South America have all been solo. Partially, this was because I knew I'd be taking some risks and couldn't guarantee a positive experience, but also it was an operational necessity since prior to this I couldn't find anyone who wanted to participate. Even so, one of my favorite parts of those past trips was sharing photos and stories afterwards. This time, I was thrilled that someone thought highly enough of the experiences I had described that they wanted to experience it for themselves. Even though we didn't meet all of our objectives, the trip did successfully achieve many of the same types of adventures that made my previous voyages interesting: riding across epic terrain, finding our way through trackless backcountry, withstanding the altitude and weather, and climbing some of the tallest mountains on this side of the world.

Attitude matters a lot. I've climbed with many people who are easygoing, but I've also climbed with some people who get very stressed when things don't go to plan. For myself, I could go either way; I certainly care a lot about reaching summits and keeping to schedules, but I also know that a large part of what I enjoy is the activity itself rather than just crossing some "finish line". In the end, it becomes a choice for me as to whether I am most focused on the end goal or on the experience. When I planned this trip, I definitely was focused on goals - there's no way you'd set out to do twenty-something 6000 m peaks in a single push if not to try hard to achieve something. However, when our plans started to shift, I was careful to shift my perspective to match. In the end, my perspective was one of the only things on this trip that I actually could control with any reliability.

Okay, enough self-actualization... why didn't we get to the summits we'd planned?

By far the most critical issue was our over-reliance on satellite imagery and topography data. The images available on Google Earth are at best 10 cm per pixel, and in most cases quite a bit worse than that. This means that everything except large-ish rubble shows up as a smooth texture. Aside from correlating other people's pictures to specific terrain features, it's near impossible to discriminate between dry sand, wet sand, coarse scree, or slopes of softball-sized rocks. As a result, a lot of the terrain we crossed was less suitable for walking or biking than we had initially guessed; we ought to have allocated more time to move through many of the areas we entered. Similarly, the altitude data given in Google Earth is all based on the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) dataset. This is an amazing resource, but the grid spacing is 50 m. This means that the vertical relief you see on Google Earth is considerably smoother than what actually exists - it's the average altitude of a 50 x 50 m patch of land. When you look at something like the El Condor lava fields, the waviness that occurs on a 10-20 m distance scale is almost entirely lost by this averaging. Overall, we made way too many assumptions about what the terrain was going to be like, and those assumptions were in general not conservative about their implications for our trip.

The type of bicycles we brought - and especially the tires equipped on them - was not ideal for what we were doing. I had brought a MTB with 2.5" low-drag gravel tires, and Trefor had set up his MTB with thinner 1.7" hybrid tires. While neither of us was able to consistently ride either the washboard backcountry roads or the Puna terrain itself, there was certainly a major difference in how our bikes handled the ground material. My wider tires could be run at lower pressure for a large and gentle contact patch, substantially reducing how much it dug-in on softer terrain. Even so, it wasn't quite enough - I could ride okay with the bike on its own, but when loaded with all my gear it still bogged down into any patch of sand.

On my subsequent 2024 expedition, I used a fat-tire bike with 4.5" tires which could operate down to less than 0.5 bar to roll over just about anything. This wasn't without challenges - including much higher rolling drag on roads - but it enabled me to ride or hike-a-bike with relative ease over sand and even scree. With that setup, the approach we took to El Condor would have been an easy-ish half a day instead of 1.5 hard days. It's not by any means a silver bullet fix, but it is a major step towards versatile desert travel.

I am also coming to understand that I might often be carrying too much gear. I have tried in my expeditions to balance comfort and conservative planning against gear weight, but I think I have a lot of room for improvement if I reassess what I carry. In particular, almost everything I have was selected more for being cost-effective rather than being lightweight. Some of my equipment is also over-specified for what I'm doing, and is more of a convenience. For example, my sleeping bag could probably be rated 10 degrees warmer, my tent could be a bivy sac, either my ice axe or trekking poles could be left home, and I don't actually need a lot of the small oddments (e.g. camera accessories) that I carry. Aside from food and water, the 40+ kg of biking, camping, and climbing gear I bring could certainly be cut down to 30ish kg if I sought out higher-performing options. My bike in particular is relatively heavy at 13 kg - I bought it because it was cheap and good enough, not because it was ideal for the application. A better MTB could definitely be had at 8-9 kg. My consumables are similarly heavier than they could be; I rarely actually eat the full daily ration of food, and I could save a few kg on average by better managing my water reserves. All told, there's a good chance I could be just as well-equipped with 65 kg of kit as with the 85 kg I brought on this trip.

Lastly, my fitness was less than it could have been, and arguably less than it ought to have been for the expedition we had attempted. That's not to say I wasn't in good shape - even having skipped a lot of workouts in the weeks leading up to the trip, I was still a well-trained cyclist in excellent health - but rather that I could have tailored my training quite a lot better for the activities I wanted to do. My cycling training got a bit haphazard for the last couple of months before the expedition, which certainly didn't help, but also I don't think I was doing the right kind of cycling. There's a saying in competitive athletics: "train like you race, and race like you train". I didn't really do that - my training did not reflect the actual demands of the expedition. I should have focused more on long endurance rides rather than the intervals that I did. Beyond this, I definitely should have done a lot more hiking, scrambling, and long walks with a heavy pack. My core strength was a limiting factor on our longest hiking days, and I've been doing these trips for long enough now that I ought to have anticipated that.

Conclusion

Well, that's about all I have to say. We went out and cimbed some mountains. It didn't go as planned, but we still had fun and nobody got (badly) hurt. I can probably do better on future expeditions by applying a few key lessons:

- Rely less on satellite imagery and SRTM elevation data for route planning - corroborate with boots-on-the-ground images and beta wherever possible

- Plan more conservatively, allowing realistic time for unknown conditions or unexpected difficulties

- Refine gear and consumables choices to save a meaningful amount of weight

- Tailor my athletic training to overall expedition demands rather than settling for general cycling fitness

I'm still undecided about what I'll do in 2025. I have a tentative itinerary through the norther Puna de Atacama with 11 summits, but I'm not sure I can spare enough time to actually do it this coming winter. I might defer that to a future year, or maybe think of something that can be done in two weeks rather than five. One way or another, I expect I'll be out there again sometime soon - lots more mountains on the list!

Links

My experiences on this trip allowed me to author a handful of new SummitPost pages:

Check them out, and be sure to like or comment the images and content that appeals to you - really helps me to understand what people want to see!

A trip report for my 2024 expedition is forthcoming - hopefully soon. Someday I'll figure out what to do with all the epic drone video I have of all of these mountains. Let me know if you have any suggestions.