Previously in Four months in Peru: From a vanished trail on Chopiqualqui to a freeway on Pisco.

Meeting Lyngve

A few hours after returning to Huaraz, there was a knock on my door. It was

Lyngve. I hadn't met him in person yet, but a while back he had sent me a message after reading that I was looking for mountaineering partners. He collected country high points and, right after Chimborazo, he wanted to climb Huascarán Sur.

![Huascaran from the southwest]() Huascarán from the road to Musho

Huascarán from the road to Musho Having lots of time in Peru, my agenda was simple: I just wanted to climb lots of alpine routes. I didn't have a long wish list. Should I still have any particular desires near the end of my stay, I planned to hire a guide, but until then I just went with the flow. Whenever I met someone who wanted to climb a route that I thought was within my capabilities, I was game.

However, short as my wish list may have been, Huascarán was at the top of it. And not just Sur, no, I wanted to climb Norte as well. I mean, high camp is the same for both, and if you're already there to climb Sur, it takes just one more day to climb Norte - assuming you feel fine and the weather holds. I didn't come across any trip reports of people doing this, but I figured, why not? So, when Lyngve wrote that his main goal would be Huascarán Sur, but that he was also keen to join me for Norte, I was happy.

We didn't take long to decide we would not hire a guide. We both had enough experience to do it ourselves. Tomorrow Lyngve would move to Edward's Inn, where I was staying, so it would be easier to organize everything, and we would head out the day after that.

Red Tape

First order of business? Deal with the red tape.

To climb anything in the Cordillera Blanca without a guide, you need a permit. It's free, but you must prove that you know what you're doing. The formal (and easiest) way to do that is to show your alpine membership card – but although Lyngve was more experienced than me, he wasn't a member of any alpine club. He's Norwegian, and I guess that heading out into the mountains is so much more a way of life in Scandinavia than it is in the Netherlands, that many don't bother to join a club for it. The only official document he had was his extreme sports insurance policy – which I knew the authorities would want to copy as well.

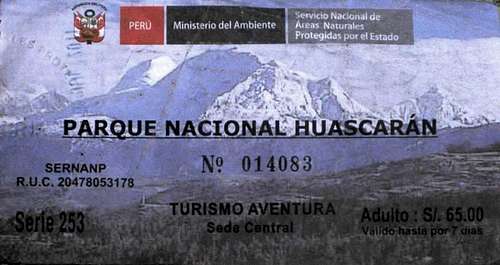

![Ticket]() 2011 ticket for the National Park, featuring Huascarán from the south.

2011 ticket for the National Park, featuring Huascarán from the south.

It's not faded, this is just the way it looks.

To satisfy the official requirements, we paid a visit to one of the ubiquitous local internet cafés, where we composed a nice formal looking letter supporting Lyngve's mountaineering credentials, including a reference to his insurance policy. Letter and policy in hand, we headed to the Huascarán National Park office, and without any difficulties we got our permit. It probably didn't do any harm that they knew me well by now, as I had been visiting their office regularly over the last month to get another permit.

[1]

You also need a park pass to enter the national park, but that's easy. No experience is required for that. For 65 Soles (23 US $) you get a ticket stating it's valid for 7 days, but, as I had found out, is actually valid for a month.

Starting points

So, how do you go about climbing Huascarán?

A normal, reasonably well acclimatized mountaineer will need at least five days to climb either Sur or Norte. To do it in five, you go from the trailhead at the small village of Musho (3100m) to the refuge at 4650m on the first day - if you prefer to, or if the refuge is closed, you can also camp outside.

When in doubt about your acclimatization, spending an additional night at base camp (4200m) is not a bad idea. All the foreign commercially guided expeditions do so, but if you go by yourself, or simply hire a local guide in Huaraz, it's up to you.

Above the refuge, the next two camps are on the glacier: Campo Uno (5300m) and Campo Dos (5850m), just below Garganta, the huge saddle between Sur and Norte. For the record, Norte actually lies northwest of Sur. The route between the two camps is dangerous because you have to climb an icefall and cross two avalanche zones.

On summit day, everybody starts early. The main reason is that you want to be on the summit early so you might have a view before the clouds move in, which is quite common early in the morning. Getting there well before the clouds is even better, so you don't risk getting lost on your way back down. If it's early enough by the time you're back at Campo Dos – which, given your alpine start, is very likely – and you still have enough energy left – not quite so likely – you can pack up and start your descent, either to Campo Uno or to the refuge. Otherwise, although it's a long way down – about 2800m in fact – if you leave early the next morning, you can still make it all the way to Musho. In contrast, many commercial expeditions only descend from Campo Dos to Base Camp on the day after the summit attempt.

Our own plan

Lyngve came fresh from Chimborazo and I had been in Peru for a few months by now, so I figured we were both more than reasonably well acclimatized. In fact, I had given seriously thought about not only skipping base camp, but skipping Campo Uno on the second day as well and going straight from the refuge to Campo Dos. Long before I had met Lyngve, I had even enquired at one of the agencies in Huaraz about hiring a guide for that schedule, but I was told they didn't want to do that, not even when I said I would pay extra because the guide would have to work harder than usual. I didn't press the issue.

We discussed whether we wanted to hire a guide, but quickly agreed we didn't. We settled on probably skipping base camp and sleeping at the refuge, Campo Uno and Campo Dos, but we would keep an open mind. If we were too slow or not feeling good enough, we could always change our plans and sleep at base camp after all, and if we were fast and strong we could still skip Campo Uno. Flexibility is one of the advantages of organizing your own climbs. At least as important perhaps, we bought plenty of supplies, so we could stay up to six days at Campo Dos, to improve our chance at climbing both summits in case of any contingencies. The down side for that was that we had a whole lot more weight to drag up the mountain...

On the move

![Huascaran from Musho]() Huascarán from Musho

Huascarán from Musho ![Want to climb Huascaran?]() Who needs a map? There is a perfectly clear sign at the trailhead in Musho!

Who needs a map? There is a perfectly clear sign at the trailhead in Musho! Edward helped us with some of the logistics, and shortly after 9am we drove off to Musho. After an hour and a half, faster than expected, our taxi already arrived at our destination. It was a simple house that served as staging area for mules and porters, and doubled as local internet café. As we had plenty of time, we asked if a simple meal would be possible? Something like chicken, potatoes and veggies? And, sure enough, as Edward had predicted, it was. I checked my messages while I waited for my food, and the local kids were playing noisy video games.

We hired an

arriero and a couple of mules to carry our kit to base camp – mules can't go higher, because a bit of scrambling is required after that and mules can't scramble.

Our plan was to carry everything ourselves from there. During the hike, I occasionally chatted with our

arriero. My Spanish wasn't very good, but we managed to understand each other. His name was Taylor. He came up with an idea: should we decide to sleep at base camp, he could already carry one of our bags up to the refuge, so we would have an easier day tomorrow. I appreciated his willingness to think ahead and be flexible. But it didn't take long for us to learn that we had no trouble with the altitude. Although I had spent more time high up in the mountains than Lyngve, he was even faster. Quickly we knew that we would skip base camp.

![Huascaran Norte from the woodlands near Musho]() Huascarán Norte from the woodlands near Musho

Huascarán Norte from the woodlands near Musho ![Huascaran Sur]() Huascarán Sur from somewhere between Musho and BC

Huascarán Sur from somewhere between Musho and BC

![A bit of rock]() Easy rock slabs between base camp and the refuge

Easy rock slabs between base camp and the refuge

Eager to make some more money, Taylor offered to carry one or our bags today himself, and I liked his thinking. He even suggested it might be possible for another porter to do a carry from base camp to the refuge, so Lyngve and I would

both have it easy today. We thought it over, and after a short n

egotiation about his fee, we agreed. And, sure enough, as we reached base camp, there was another porter and we continued straight away.

![Refuge Huascaran]() The refuge

The refuge

Lynve and I didn't have much weight, and could move fast up the slabs. The scrambling sections didn't pose any problems. Taylor proved to be very strong and handled the weight easily, but the second porter was struggling a bit. Still, the refuge turned out to be closer than expected and we got there around 5 o'clock, well before sunset. We still had an hour to enjoy the fantastic scenery.

![Clouds over the Cordillera Negra]() Clouds over the Cordillera Negra

Clouds over the Cordillera Negra ![Huascaran panorama]() The twin peaks from the refuge

The twin peaks from the refuge

![Last light on Huascaran Sur]() Last light on Huascarán Sur, from the refuge

Last light on Huascarán Sur, from the refuge ![Last light on Huascaran Norte]() Last light on Huascarán Norte, from the refuge

Last light on Huascarán Norte, from the refuge

Campo Uno

![Huascaran Norte]() The rocky slabs above the refuge, with Huascarán Norte towering above

The rocky slabs above the refuge, with Huascarán Norte towering above![Huascaran Sur]() The rocky slabs above the refuge, with Huascarán Sur towering above

The rocky slabs above the refuge, with Huascarán Sur towering above![The shiny shield on Huascaran Sur]() A big cairn on the slabs above the refuge, dwarfed by Huascarán Sur.

A big cairn on the slabs above the refuge, dwarfed by Huascarán Sur.![Time to put on crampons!]() At the edge of the glacier: time to put on crampons

At the edge of the glacier: time to put on crampons![Man on the mountain]() Huascarán Sur looks small, but we're only around at 5000m or so, and that "small hill" is 6746m high!

Huascarán Sur looks small, but we're only around at 5000m or so, and that "small hill" is 6746m high!![Huascaran Norte from low on the glacier]() Huascarán Norte from low on the glacier

Huascarán Norte from low on the glacier![Campo Uno on Huascaran]() Tents at Campo Uno

Tents at Campo Uno

From the refuge, it was a short day to Campo Uno. A couple of hours on rocky slabs, then a couple of hours on a very easy glacier with virtually no crevasses, that's all. No need to rope up. We left late, took it easy because of our big packs and still arrived early in the afternoon. Plenty of time to take photos, and Campo Uno is an absolutely stunning setting for that!

On our way up, we met a Spanish climbing party. According to the most recent weather forecast that they had heard, after tomorrow the weather would deteriorate somewhat. Therefore, they planned to make their summit bit directly from Campo Uno, starting very early tomorrow morning. I didn't think I would be able to do that, but since we had plenty of supplies to wait out any bad weather, we didn't have to.

![Huascaran Sur: The Shield]() The Shield, a remarkable sheet of ice on Huascarán Sur. A difficult but quite popular route follows the left hand side. Some parties go up in the middle or further right, but that's a bit harder still.

The Shield, a remarkable sheet of ice on Huascarán Sur. A difficult but quite popular route follows the left hand side. Some parties go up in the middle or further right, but that's a bit harder still.![Sunset from Campo Uno on Huascaran]() Sunset over the Cordillera Negra from Campo Uno

Sunset over the Cordillera Negra from Campo Uno![Alpenglow on Huascarán Norte]() Alpenglow on Huascarán Norte from Campo Uno

Alpenglow on Huascarán Norte from Campo UnoCampo Dos

![Huascaran Norte from Campo Uno]() Huascarán Norte from Campo Uno, the next morning. See that saddle up there? That's where we have to go.

Huascarán Norte from Campo Uno, the next morning. See that saddle up there? That's where we have to go.![The last of the easy terrain for the day]() The last of the easy terrain before we enter the icefall above Campo Uno

The last of the easy terrain before we enter the icefall above Campo UnoToday was the final day that we had to carry our heavy packs up the mountain. In fact, because everything was going well and we had so many reserves, we decided to stash some of our supplies at Campo Uno. Reducing our weight seemed more important than having everything up there. And if necessary, we could come down to get it.

The route between Campo Uno and Campo Dos is the most dangerous part of the whole climb, regardless which of the two summits you aim for. It passes an icefall, pretty wild in places, and two active avalanche zones where the debris betrays the dormant danger even when everything is calm. From what I had read, conditions vary over the years and it can be difficult as well, but we actually found it pretty easy. We didn't need a second ice tool anywhere. There are plenty of snow bridges, and apart from the obvious visible ones, I can't escape the feeling that there must be some hidden crevasses in certain places as well. Unlike yesterday, we are roped up.

![Detail of the icefall on Huascarán, upwards from Campo Uno]() Detail of the icefall

Detail of the icefall![Ice formations on Huascarán]() Holes in the glacier

Holes in the glacier![Icefall detail on Huascarán]() Detail of the icefall

Detail of the icefall

After first gaining altitude on the slopes of Huascarán Sur, the route traverses towards Garganta. It seems to last a long time, but then suddenly Campo Dos appears when we're virtually there. It's a 150m below the saddle proper, so if a strong wind is blowing over it, the camp is somewhat sheltered.

As we arrive, we meet the Spanish team again. They look pretty exhausted, but they have made it to the summit. One of the climbers explains that there is a pretty steep section much higher up, near the summit. I don't quite understand how much higher and how steep, but I'm confident that we can overcome whatever we might encounter. We've each got two ice tools, just in case.

The wind starts picking up shortly after we have put up our tent. We have to zip it up to keep the snow drift at bay. Aiming to start real early, we turn in straight after dinner.

![Campo Dos on Huascarán]() Campo Dos, with Huascarán Norte in the background

Campo Dos, with Huascarán Norte in the backgroundChange of plans: Norte

The wind is blowing strong, there is the occasional little bit of snow – or is it spin drift? – and the highest reaches of the mountain are enveloped in clouds. Unpleasant as that may be, it's all irrelevant: Lyngve has a headache, and while it's not so bad that he needs to go down, it would be too dangerous to go any higher. Our alpine start is out of the question. We stay in our tent and go back to sleep.

By the time the sun comes out, I decide to head out. The wind is still strong, and I borrow Lyngve's goggles to protect my eyes. I didn't bring any myself, because if conditions are so bad that I really need them, I usually prefer to stay inside. But whether it's better now than in the middle of the night, or it just seems that way in daylight, I judge the conditions good enough to at least have a look higher up. We agree that, if all goes well, we'll try climbing Sur tomorrow, so today I'll go the other way, to Norte. Besides, since Sur is climbed much more often, it surely will be easier to recognize traces of a trail there, so scouting part of Norte is more useful.

While the contours of the mountain make the summit of Sur invisible from Campo Dos at all times, Norte is pretty clear. Shards of clouds occasionally hide the highest parts, before the wind blows them away again. The lower parts stay clear all the time, and even the sun has come out in force now.

Even before I reach the col, I take a wrong turn. From camp, it starts out clearly, up a snow ramp that leads to the edge of a huge crevasse. To find a way across, I have to decide: left or right? Thanks to the spin drift and my somewhat watery eyes – they are still adjusting to the cold – I can't make out the trail. It must be gone. I don't remember why, but I decide to go to the right. As I would find out later, that was the wrong way, but after following the edge of the crevasse for a while, I eventually find a safe and easy way across and reach the huge saddle.

Surprisingly, it's a bit less windy. Thanks to my wrong decision, I'm closer to Sur than to Norte now, and the advantage for that is that I get a really good view of the slopes of Norte. I study the face, looking for a way up. The right hand side is a gigantic jumble of seracs. I definitely don't want to be near any of those. The left hand side looks a lot more inviting, but a long bergschrund stretches along the bottom, protecting access to it from Garganta. Above that, I don't see any immediate problems. That doesn't mean there won't be any, but if I can't get over the schrund, it doesn't matter.

There is an obvious snow slope, devoid of any obvious crevasses, leading to the highest point of the schrund, and there is another good looking snow slope above it. Perhaps I can cross there?

![Huascaran Norte panorama, from Garganta]() Norte from Garganta. It looks close, but this is still almost 700m below the summit.

Norte from Garganta. It looks close, but this is still almost 700m below the summit.

I took this picture a month later. On my original visit, clouds swirled around the summit ridge, but most of the mountain was visible. I was too focused on my climb to think much about taking pictures. On my second visit, the mountain was still the same and because this clearly illustrates my thought process when thinking about which route to take, I've used this picture here.

On the right is a labyrinth of seracs: no way I'm going up there! As if to emphasize the danger, there is a recent avalanche debris field in the center.

In contrast, that big snowfield left of center looks inviting. It will be easy to get up there. However, there is a bergschrund guarding access to the next snowfield and the south ridge above it, which is the normal route. From this distance, I can't see if there is a way across the schrund. I'll just have to go there and have a closer look.

I head up the slope. The snow is in great shape, packed hard. It's not difficult, but I pace myself, mindful of the fact that I'm alone and if I do manage to get really high, it's imperative that I have enough energy to get back down safely. As I get closer to the schrund, it seems to get bigger and bigger. Down below, it didn't look like it, but it's massive, and even if it had not been too wide, the other side is close to vertical! There is no way I can possibly cross it here!

![Ice wall on Huascaran Norte]() The ice wall

The ice wall I follow the schrund to the left, descending along the way. The scenery is breathtaking, but I have to admit I was more focused on finding a way across than taking photos. Sometimes it's wide, sometimes not, but the wall is always there. After following it for quite a while, and descending some 100m in the process, I finally reach a snow bridge. More to the point, it's an ice bridge, and a very solid one. The only problem awaits me on the other side: it looks pretty steep. But it's much easier than the vertical wall earlier on.

![Wild ice low on the Huascarán summit route]() Wild ice low on Huascarán Norte

Wild ice low on Huascarán Norte ![It's a bit steep here!]() The crux

The crux ![Ice formations]() Swirling clouds and ice formations high on Huascarán Norte

Swirling clouds and ice formations high on Huascarán Norte I estimate it to be 60º at most, and less higher up. And, at least as important, it's not ice but hard packed snow, and I discover it's easy to kick in my crampons and place my ice tools without any real danger of slipping. Nevertheless I'm very concentrated, fully aware that I can't afford to make a mistake here. My adrenaline runs high, and I feel very much alive. I'm thoroughly enjoying myself. This is what it's all about!

It's still windy, and so I keep going with two ice tools even as the gradient eases. It must have looked funny to an impartial observer, a crawling mountaineer...

I'm on the south ridge now, and it's wide and not particularly difficult. I have a free choice of where to make my way up. The wind is coming from my right, so I move to the left so I don't have to face it head on. And before long I notice that it's actually less windy on the left side of the ridge. I've reached the wind shadow of the mountain.

![Huascarán Norte]() High on the summit route

High on the summit route

I keep plodding upwards. Occasionally I pass a somewhat steeper section. Since I have them anyway, I keep using my two tools, but one would suffice now. As I'm getting higher, the occasional cloud drifts by, temporarily impairing visibility. I look back down frequently, doing my best to memorize the key points for the way back in case it gets worse. I hesitate. Should I turn back already? But every time, the clouds are blown away quickly and I can clearly see from where I came again.

![Mixed visibility high on Huascarán Norte]() Mixed visibility and signs of crevasses

Mixed visibility and signs of crevassesAround 6500m the terrain changes. It's markedly less steep now, and the ridge is not as wide. I see a big bergschrund, which I easily go around. There are several other obvious crevasses, and some barely hidden ones. I go real slow now, and frequently prod the snow ahead of me with my two tools before taking another step. The clouds descend on me again, and this time they are here to stay. But since the ridge is not really wide anymore now, I know I can't get lost. I might not get a summit view, but poor visibility won't stop me now.

![Ice formations on Huascarán Norte]() Ice formations

Ice formationsI see what appears to be the summit ahead. However, my altimeter reading is too low. It must be a false one. And, sure enough, when I get there, I see that the ridge continues. The slope is real gentle and the going is very easy now. Before long, I can go no higher. Although visibility is poor now and I can't see far, it's just enough to see that it goes down pretty steep on all sides, with the exception of the ridge that I just came from.

Strangely enough, it isn't windy at all on the summit. I don't know why, but at least it explains why the clouds are not blown away. I'm happy that I have made it all the way, but don't stay long up there. I still have to get down safely, and in case the clouds will build up again, I may need more time to find the route.

I descend a slightly different route at first, high on the ridge, because it looks easier. And at first, it is, but I pay the price when I reach the bergschrund at just over 6500m. From where I am, I can't easily go around it anymore. Either I go back up for a while, or I have to climb down a short steep slope and then jump across. Not wanting to spend more energy by going up, I start climbing down. However, the snow is powdery, not very solid, and I find it hard to avoid slipping. I go up a bit, to where the snow is more solid and traverse until I find an easier place to cross. I descend again, and, close to the crevasse, I jump and land safely on the other side.

![Clouds moving in again high on Huascarán Norte]() Clouds moving in and out

Clouds moving in and outThe clouds came and went now. At times whan visibility was poor, I waited for the wind to blow them away. It never took long. Below 6400m, conditions were better, and often I could see a long way down. Still lower, I recognized traces of an old trail, and followed it for a while. It was somewhat more easterly on the ridge than where I had climbed it, and found it pretty easy going. But lower down, it got steeper, until I got close to the upper lip of the huge bergschrund protecting access from Garganta.

There was a snow stake. Below it, the slope got steeper and steeper, and I could see over the edge, but as I had walked along the other side of that bergschrund earlier that day, I knew that I couldn't possibly descend there without a rope! It was too steep, I might fall off the mountain, and if I didn't, the schrund was too wide down there to get across. In fact, I'm still puzzled that anyone would even want to try it. This route was not for me. I wanted to use the ice bridge that I had crossed on my ascent!

Although I had not followed my own trail, I knew that it had to be a bit further south. I climbed up a bit, to where it was not quite as steep, and then traversed to the south. And, sure enough, it didn't take long to find the steep slope above that familiar bridge.

After that, the rest was easy. As I approached the edge of Garganta, I even found an old trail. More proof that people had at least attempted to climb Norte not too long ago. This route crossed a few more snow bridges than on my own route early in the morning, but was a lot shorter. But I also knew now that, should these bridges unexpectedly collapse, there was an alternative.

When I got back at our tent, Lyngve was a bit surprised that I had made it all the way to the summit. Not

too much, mind you, as he had actually spotted me high up, earlier in the day.

The rest day agreed well with him, and he felt better. Now it was my turn to be somewhat surprised, when he said that he now would be happy if we would only climb Sur. I had in fact expected us to try climbing Sur tomorrow, and Norte again after that, provided the weather would be good enough. And if not, we had enough supplies to wait longer. I suppose Lyngve had still not completely recovered, and since his main goal was to climb country highpoints, Norte had been only a small bonus for him anyway, making it easy for him to give it up.

Sur, into the clouds

We had set the alarm at 2 am, planning to leave at 3. As we woke up, Lyngve's stomach was slightly out of kilter, but not enough to stop us. I crammed down a large breakfast, knowing I would need the energy later in the day. However, when we looked outside our tent at 3, it didn't look good. It was windy again, snowing very lightly, it was cold and, most importantly, the higher parts of the mountain were shrouded in clouds. We decided to wait.

We went back to sleep. Occasionally, when we woke up, we would check again, but saw no improvement. By 7, and with daylight now, I thought it was good enough to at least go out and see how far we could get, and Lyngve agreed.

We didn't have to waste any time searching for the shortest way to Garganta, across the two snow bridges. Surprisingly, one already had a hole in it – that wasn't there yesterday! We roped up...

It felt colder than yesterday, but the wind wasn't as strong. We crossed Garganta to reach the base of the steeper NW slopes of Sur. We could see most of Norte, but the clouds on Sur looked thick and were hanging lower. Lyngve thought we didn't stand a chance today. Moreover, the cloud patterns yesterday evening reminded him of what he knew from Aconcagua, where similar clouds were a sure sign of a couple of stormy days. Personally, I'm not particularly familiar with cloud patterns and weather forecasting – all I knew was that, usually, bad weather in the climbing season in the Cordillera Blanca doesn't last long. But it can be bad indeed, and camping at 5850m might not be the best place to be when that happens.

Lyngve wanted to turn back and descend to the refuge. However, mindful of the unlikely success I had enjoyed yesterday, I wasn't ready to give up just yet. We talked it over, and agreed that he would go down, pick up his gear but leave all the supplies in our tent, pick up our stash at Campo Uno and continue to the refuge, while I would continue to go up, at least for a while. Later, back at Campo Dos with or without success, but with plenty of supplies, I could then decide to descend or stay longer.

A learning experience

In hindsight, I believe that we made a mistake here. Not by trying to climb Sur solo, I was, and still am fine with that, and not in going back to Campo Dos alone either, but because of the route between Campo Dos and Campo Uno. We had read about it, but had only followed it once, on our way up to Campo Dos a couple of days earlier. The route was in good shape then and visibility was fine, and even though I noticed plenty of crevasses, and not all of them very obvious, I didn't really think much about it. But I should have realized it would be dangerous to go there alone, unroped. It would have been better to turn back together, or to agree that Lyngve would wait for me at Campo Dos. I don't remember why we didn't even consider that. Mind you, we did discuss our options rationally, and were both comfortable with our choices – I believe that if either of us had mentioned any reservations about descending alone, we would have stayed together. Nevertheless, I've learned from this, and in a similar situation I won't make the same mistake again. But this realization would only come later. At the time, I was still hoping for a repeat of yesterday's success.

Into the clouds

As Lyngve turned around, I continued on my way up. At first, it was easy going. Despite the spin drift and the tiny amount of fresh snow, the trail was still clear most of the way. And in addition, there were wands marking the route. But higher up, as I entered the clouds, it got harder. The trail was twisting and winding through an icefall, with the occasional sudden turn, and a few times I had to search a bit to find it. Having less visibility also meant I couldn't always see the next route marker. The technical difficulties were no problem. It never got steeper than 50º, and while I had to cross an interestingly sculpted ice bridge over a big crevasse, it was very strong. But the route finding slowed me down.

![Poor visibility and wild ice high on Huascarán Sur]() Poor visibility and wild ice... not an ideal combination

Poor visibility and wild ice... not an ideal combination![Ice sculpture in poor visibility high on Huascarán Sur]() This kind of visibility forced me to turn back

This kind of visibility forced me to turn backEventually, I reached a point where I didn't see where the trail continued, and couldn't spot the next marker anywhere. I looked at the terrain, to judge the most likely place to continue. One of my attempts was to traverse along a small bergschrund at the bottom of a steep slope – that is, at first I followed the lip of the crevasse, thinking that the indentation was a faint trail, and only then I saw what it really was.

After trying the more obvious as well as some less obvious ways to continue, I concluded that the only reasonable way would be to climb a rather steep slope. Perhaps this is what the Spanish party had told us about? I started climbing it, feeling confident with my two tools – but in the poor visibility, I quickly lost sight of what was below me, and, more importantly, I couldn't judge the steepness of the slope. I finally knew that I had gone as high as I could today. To continue really wouldn't be safe anymore.

Back to the refuge

It wasn't all that late, and trusting Lyngve's weather forecasting skills I decided to go back to the refuge as well. I even had a vague hope that if Lyngve had rested a bit at Campo Dos, I might catch up with him. And so I descended quickly.

At Campo Dos, there was a new group of six, but no Lyngve. I packed up and headed down after him. You would think that six new climbers coming up, plus Lyngve going down, would improve the trail, but thanks to the wind, it wasn't clear at all, and on some stretches it was completely gone. There were a few route markers, but widely spaced. I got off trail...

![A crevasse near Campo Dos on Huascarán - Campo Uno is visible in the distance]() A crevasse near Campo Dos. This one doesn't worry me, it's visible...Note that Campo Uno is already clearly visible in the distance. But I'll need a few more hours to find a way to get down there.

A crevasse near Campo Dos. This one doesn't worry me, it's visible...Note that Campo Uno is already clearly visible in the distance. But I'll need a few more hours to find a way to get down there.Visibility was fine now, well below the clouds, so it was easy to spot the tents at Campo Uno from high up, and I could even make out the refuge in the distance. A bit lower, I came across traces of a trail. They were clear enough, but didn't seem big enough to be from a group of six. Perhaps Lyngve had gotten off trail too?

But the traces faded away, and I had to find my own way down again. I had studied the area very well though, and knew that the biggest problems with the crevasses and seracs would be directly below Garganta, and the more you traverse towards the south on the slopes of Huascarán Sur before descending, the easier it should be. In fact, the normal route traverses as well, but when in doubt, I figured, when I traverse too little, I'll be in trouble, while if I traverse too far, it's only a detour. So, whenever I didn't see a clear and easy way down, I traversed some more.

I had to retrace my steps a couple of times when I found myself blocked by an unexpected crevasse, but in the end it worked out quite well. While it certainly was a longer route down to Campo Uno, and I needed more time searching for it, it wasn't particularly difficult.

Then, suddenly, it appeared as if there was no way to go down any further. I had descended into a dead end. The only way that wasn't blocked by crevasses was where I just came from. I was getting tired, and didn't fancy lugging my big pack up again to search for another way down.

As I had a last good look around, I was fortunate enough to spot a possible solution: On the other side of one of the blocking crevasses was a short wall of ice. The crevasse wasn't wide at all, but I had dismissed crossing it because of the wall. But now I noticed that it was low enough to reach the top with my hands. If I could climb up that very short vertical step, I might perhaps continue without backtracking. I reached, and could just put my pack up there. Free of the extra weight now, it was easy. And once I got up there, a big white expanse without any obvious difficulties opened up before me. Without further problems I walked back down to Campo Uno, where I arrived well south of the normal route.

As I said, my route down had not been particularly difficult. But not being on a trail obviously means a higher crevasse risk, and I knew there were plenty of those...

Shortly past 5 o'clock, one hour before darkness, I reached the refuge. That might seem close, but with a tent and plenty of supplies, it wasn't. Once below 5300m, you can camp pretty safely all over the place.

In the refuge, Lyngve told me that he had also experienced trouble finding the route on his way down. And at one point he reached a wide crevasse where he remembered a perfectly fine snow bridge from our ascent, but it was totally gone now. If the route would continue to deteriorate, Lyngve thought that, in couple of days, it might not even be possible anymore to reach Campo Dos! I hadn't noticed, but I can't say if that was because I didn't remember the snow bridge or because I got off route higher up.

Mike

Around 6, a lone hiker arrived at the refuge. Right on time, as it was just before nightfall. His name was Mike, and as we got to talking, he explained he was a paraglider pilot and sometimes organizer. The reason for his visit was sobering. More than a week earlier, a French paraglider had gone missing in the area during a local paragliding event. Initially, there was a lot of confusion where he might be, and the search efforts had been slow to get off the mark, and not been looking in the right area.

Mike had flown in from Chile to assist with the search and rescue operation, get search planes off the ground and pay some (big) bills – getting rescued in Peru isn't free of charge and the effort depends on what you pay for. He told me that some time ago he had spotted something yellow on the ground from a search plane, south west of Huascarán Sur, and in the vicinity of the refuge. It had turned out to be the paraglider. Although his friend was found, it proved to be too late. Sadly, it turned out that while he had survived the crash, but injured and unable to move. He survived for several more days before succumbing to hypothermia. Mike had come up to the refuge to visit the site, and pay his respects.

[2]

Bright and shiny

Next morning, we woke up to bright sunshine and almost completely blue skies. Only a few scattered clouds were hanging around some of the summits. Not surprisingly, the biggest of those was hugging Huascarán Sur – it's not unusual for high mountains to have their own weather conditions, and this wasn't the first time I saw a cloud on Huascarán while the lower summits where clear. But as clouds go, this was a benign one, and by 7 am, we could still see the summit. It did appear a bit windy up there, but apart from that, it looked like it would have been a fine day to be up there.

![Huascaran panorama from the SW, from the refugio, with the sun behind Sur]() Blue skies with just a few clouds on Huascarán Sur early in the morning. Note that Norte is in fact clear!

Blue skies with just a few clouds on Huascarán Sur early in the morning. Note that Norte is in fact clear!

Lyngve was not amused when he saw that. He realized that he had missed a good opportunity to reach the summit because he had been too pessimistic with his interpretation of the cloud patterns yesterday.

I was philosophical about it. It's too easy to say that that going down to the refuge had been wrong. I believed that, based on what we knew yesterday, going down to the refuge had been the right decision. With our limited knowledge about the weather in the Cordillera Blanca, we thought it better to descend, and I rather make an error on the safe side like that, than find myself bogged down in my tent in a storm high on a mountain.

Despite the 25kg on my back, we made short work of the 1500m to Musho. The weight and the speed of that descend made my quads ache for the next two days...

Back in town, I had a couple of rest days while I waited for Pierre, a French mountaineer I had met earlier. He had been to the Cordillera Blanca often and climbed many of the better know routes, so we had already agreed to have a go at a little known peak in the south: Nevado Uruashraju. I'll have another go at Huascarán Sur later.

Lyngve had a short rest as well, but since he didn't have the luxury of time to wait patiently if someone else would turn up for another attempt at Huascarán Sur, he decided to hire a private guide for it. And although it turned out to be hard work, he succeeded on his second try.

[3]

The story continues here: A forgotten beauty in a quiet corner of the Cordillera Blanca

Notes

![Huascarán Norte]() Clouds swirling around Huascarán Norte, seen from the refuge

Clouds swirling around Huascarán Norte, seen from the refuge The discussion about letting unguided parties climb in the Cordillera Blanca flares up occasionally. I hope it remains possible, but I won't be surprised if at some point the rules will change. Recent developments in Ecuador might fuel a renewed discussion in Peru. Now, I don't mind hiring a guide occasionally, especially when I'm climbing at the edge of my comfort zone, but if I can't climb unguided in the Cordillera Blanca at all anymore, I'll go elsewhere. It will still be a sad day when that happens, because I would like to come back one day for another extended visit.

For the record: the small print in my insurance policy puts a limit on the duration of a trip, and I knew I was long past that already. So, while Lyngve had the proper insurance but no alpine club membership, for me it was the other way around. But if you get in trouble high on a mountain in the Cordillera Blanca, chances of getting rescued are quite poor anyway: your cell phone may not work (although coverage is improving rapidly), there is usually no helicopter in the area that can fly high enough, and even if there is, it won't until the owner is absolutely sure he will get paid, and to have any chance at all for that to happen quickly, you basically need a good friend down in the valley with a wad of cash. The tragic accident and ensuing search and recovery operation of the paraglider hammers that home...

[2] Although sad for those that get in trouble, I find it perfectly understandable that search and rescue in Peru is totally different from what it is in, say, the Alps. A rich country can afford to have rescue helicopters standing by, and worry later if those that are rescued can pay for it or have insurance coverage – in fact, in many western countries you won't even get billed. But in Peru, the number of people needing rescue in the mountains is small and the country isn't rich, so there are many better ways to spend the money. Visiting mountaineers know and accept this, and so do paragliders. If you have any lingering doubts about where money might be more useful, just pop into one of the local hospitals (I did, once, fortunately only with a minor injury), to give just one example.

As for the paragliding accident, it's been widely covered in the press. Not surprisingly, many of the reports published shortly afterwards turned out to be speculative and incomplete, to put it mildly. Here is

a thread about the accident that rings true to me. My condolences go out to Xavier's family and friends. May he rest in peace.

[3] Here you can read

Lyngve's own account, as well as

his second, successful attempt.

![Last light on Huascaran]() Last light on Huascarán, from the refuge

Last light on Huascarán, from the refuge

Comments

Post a Comment