Prologue: Independencia ruin 21,000 feet Aconcagua

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Independencia Hut

Independencia Hut

I have reached Independencia hut. It looks just like in all the photos I have seen. After over two years of anticipation I cannot believe I am here, up at 6400 meters - nearly 21,000 feet above sea level. The last time I was this high was back in 1987.

The hut is a ruin and little bigger than a tent. Most of the planks in the roof are missing. Even in the rosy light of soon after dawn, it doesn’t look an attractive place to stay the night. I find out later that just three nights earlier a party of people did just that – and one had died and the rest sustained severe frostbite. I saw the body of the one who died up here, being brought down to Cólera Camp yesterday, just after I arrived there – at that wind blasted boulder field, 19,500 feet up on the North side of Aconcagua. I didn’t know then that the Guardaparques had brought him down from here. I didn’t know the body was that of an Australian man, in his early 60’s. I thought the body was that of a Polish man, known to have gone missing during the recent storm – and still missing, so far as I know.

The weather is perfect for my summit attempt today. At the current time, around 9am, the sky is completely clear. As the sun rose two hours ago, the temperature was a frigid minus 25 centigrade. It is around minus 20 now – and I have to keep a constant watch on how my toes are. My new Asolo double boots are not as warm as the version of the same boot I had 24 years ago, on Broad Peak. This morning, before I left the tent, I slipped chemical heat pads between my sock layers in anticipation of the cold. But they don’t seem to do much – and my toes are burning and tingling in that way that precedes the onset of numbness… and the threat of frostbite. Like those poor souls suffered, who spent the night here.

Although conditions are good I am not confident of summiting, because of my cold feet. I try to keep wriggling my toes periodically. It was early frostbite which put paid to my attempt on Menthosa back in 1983, when we had to turn back at around 6100m, just about 300m below the top. I am as high as the summit of Menthosa now.

Still talking of chemical heat pads: I have done rather better with the ones designed for hands – and two of which I have in my camera bag, as well as inside my big Mountain Equipment gauntlets. My fingers are toasty warm and my camera is working just fine. It is a pity those types of pads were too big to fit inside my boots.

I swallow some energy gel ‘goo’ and some water – still unfrozen in my insulated water bottle. My throat is sore and parched in this freezing dry air – and if I were to try to speak, it would be in a painful croak. But there is no one to speak to. At the moment I am completely alone, having been the first to set out from Cólera this morning.

The journey to get to this point has been amazing – right back to the first step I took into the Aconcagua National Park at Punta de Vacas 14 days ago, 14,000 feet below my current elevation and approaching 40 miles away. Before that things weren’t so good – in the two days I had in Buenos Aires with my wife – before she headed off to Baraloche and a horse trek across into Chile - and I headed for Mendoza, on my way here.

We got ourselves mugged in La Boca – within hours of steeping off the plane from the UK. Here I shall digress a little…

Mugged in La Boca, Buenos Aires. Sunday 30th January.

The attack came from behind and to the left. My wife and I had walked into an ambush. I hadn’t seen it coming. Leila had – and just had time to say urgently ‘I think we should get across the road…’ when the flurry of blows started to the back and left side of my head.

I had been distracted by a thin youth aged about 18 staggering towards us with a bizarre gait – as if he was suffering from some sort of neurological disease. Clearly I was meant to be distracted – so I didn’t see two or three others appear and start aiming punches at my head. Then, also as they intended: I was stunned and for a long few seconds frozen into immobility by the unexpected violence of their attack.

The blows to my head were noisy rather than painful. With an abrupt bang I was aware that both my cap and Aconcagua grade sunglasses were knocked off my head – with another blow rather than a snatch. I was dimly aware of Leila off to my right. I could hear her making sounds of distress, which sounded to be about my predicament, being attacked by these youths. She later said she thought they were killing me.

But then purposeful thought returned. I saw one of them had got Leila’s leather wallet – a colourful thing on a string, she habitually hung on a cord around her neck – and thought was safe hanging under her arm. That wallet contained all of her valuables: money, credit cards, mobile phone etc. Without it her two week horse trek probably wouldn’t happen. I still wasn’t feeling fear. But a terrible feeling of purpose came over me. I had to get that wallet back. No matter that the first commandment in the manual of how to be mugged said that you let your assailant(s) take whatever they took – and concentrated on getting away.

Still with that feeling of desperate purpose I went after the wallet. It didn’t occur to me that anyone might be doing anything to Leila now that they had her wallet. Blows were still raining down on my head – still rather ineffectually. But with a few quick strides I launched myself at the youth who was holding the wallet and grappled with him. I tried to trip him and throw him down onto the road – my arms pinioning his. But I couldn’t seem to trip him though and my best efforts merely shook him from side like a rat in the jaws of a terrier.

The blows were still raining on the back of my head as I grappled with the holder of the wallet. My recall of the next seconds is blurred. But I do remember that at some point his unprotected head swam into my field of vision. In the madness of it all I recognised I could head-butt him. Give him a Glasgow kiss as they say… But I have never head-butted anyone in my life. It seemed like using nuclear weapons – and I felt that there was a danger it could escalate the conflict to a new level – more deadly than grappling and heaving and the rather ineffectual punching. His head jerked out of range and the opportunity was gone. At some point I swung a punch at someone – the blow connected with something solid. But I was no better a fighter than they were – and I don’t know where or who the blow connected with.

But I got the wallet.

Abruptly, before I could do anything with it, it was snatched away again. I went after it again and the struggle went on – by now still probably only mere seconds after the conflict had begun. A distant part of me thought that all the action was all still just centred on me and the wallet – and that Leila wasn’t part of what was happening. But in the confusion of the post mortem afterwards, I remembered that I stopped hearing the sounds of her distress at seeing me being attacked…

Back to the wallet: I don’t know how, but I got it again. But there was still more than one of them attacking me and again they or someone got it back. It was like a ‘ruck’ at Rugby – fighting for possession of the ball. I was never any good at Rugby, anymore than I was at street fighting… but somehow, in my desperation, I won – and they lost possession of the wallet for the last time.

There it was, laying on the road – partially torn open – and Leila’s rather smashed up looking mobile phone was on the dusty surface beside it – as was a pair of sunglasses. I was no longer being hit about the head and I was aware of just one of them facing me on the other side – still potentially challenging me for possession…

But he backed off.

I swept up the three items and clasped them to my chest as I swept round, instinctively looking out for new threat. I saw a number of people all round – but had no idea who was an attacker and who was just a spectator. The only one of our assailant’s faces I had registered was that of the bizarre staggering youth, who had distracted me at the start of the nightmare. I didn’t see him now. I continued to swing round, now looking for Leila, expecting to see her standing shocked and bewildered – but out of harm’s way.

She was face down in the gutter – moving feebly – and one of them was on her back. For the first time I felt emotion. I felt all the horror and shock at the knowledge that she was hurt. I also felt guilt: whilst I had been fighting over a wallet; a mere possession; she was still being attacked. And now she was hurt.

I got to her in a few quick strides, dropping the wallet, phone and sunglasses into the dirt beside her. I grabbed the youth on her back and threw him out of the way. I spared him no further thought – not even anger. That came later. If he had had a knife he could have filleted me from behind at his leisure. But like the others he (presumably) melted away. We later became aware that by normal La Boca standards, these weren’t very good muggers.

Then I saw the blood. Masses of it – spattered all over the kerb, in the gutter and all over my wife’s shoulders. Still moving slightly, I could also hear her moaning softly. Now I felt terror and helplessness – but the Doctor in me urgently sought to track the source of the bleeding: to try to do something…

I helped her to her feet. She was confused and didn’t appear to know what had just happened. As I helped her up a part of me recognised she was holding a bloody and partly shredded plastic bag tightly against her stomach. It just contained a pair of shoes – and we would later work out that she must have been defending this pair of shoes from her assailant. Like me, she also hadn’t read the first commandment in the how to be mugged manual. We came to recognise that we were very lucky they we had such crap muggers.

The blood was pouring from a deep gash under her chin. My terror turned to blessed relief, which washed over me like a warm comforting shower. This was something I could deal with…

Leila was still confused – and she had no idea she was bleeding like a stuck pig. Somewhere I found a little pocket pack of paper tissues – and I pressed a wad against her wound. It was some moments before her confusion lifted – and she became aware of me trying to attend to her – and saw the blood. Abruptly she became frightened.

‘It’s OK’ I tried to reassure her ‘it is just your chin… coming from underneath. Bleeding a lot but… it is something I can deal with.’

I carried suture equipment in my first aid kit, back at the hotel. We had passed a hospital a mile or two back, but it had looked a grim sort of place – and I felt an overwhelming feeling of protectiveness towards my wife, that I wanted to take care of her myself.

‘Let’s get back to the hotel’ I said.

Getting her to hold the bloody wad of tissues to her chin I crouched in the gutter and picked up the wallet, shattered mobile and pair of sunglasses – and I pushed them into what was left of her tattered plastic bag, along with her shoes. Then holding this under one arm and supporting Leila with the other I turned us back out of the side street towards the main boulevard we had just left, before we walked into the ambush.

Abruptly I became aware that the same strange youth who had distracted me earlier, was there in front. He raised his arms and took a couple of steps towards us. The adrenaline was still flowing. I braced myself for another attack..

Just as abruptly he turned – and was gone.

I don’t know if he intended to come at us again. I didn’t see any of his fellow muggers, but then I wouldn’t have recognised any of them anyway. A number of young people in the street stood by watching us impassively. Nobody moved to help – but more importantly, nobody moved to attack us again either. Much later, I realised that the pair of sunglasses I had scooped off the road were not ours – but must have belonged to one of our assailants. Maybe the youth was going to try and re-claim them.

Now that we were no longer being threatened I suddenly felt my mind being overcome by a sort of blankness. I was supporting a still bleeding Leila. But it was a struggle to think now – and it seemed too much to try to work out what to do. Yet we had to – we were two miles from our hotel in a dangerous part of town – and my wife was injured.

Between us we worked out that we needed to get a taxi – and we staggered unsteadily towards the main road, looking into the heavy traffic for the black and yellow cars, which we knew were taxis. We saw several – but nobody would stop. I ran towards one out into the road in my frustration – but then felt anxious at leaving Leila unguarded – and ran back.

Unable to stop a taxi, we ended up stopping at the hospital we had passed. Medical staff were taken up with a terrible accident involving a small child and we were told they couldn’t help us. But they did allow Leila to get cleaned up and gave us a gauze swab soaked in iodine, to apply to the gaping laceration on her chin.

Back at our hotel, an hour or so later, I used 4 tiny sutures to close her wound. The whole area was badly bruised – and continued to ooze blood, until I applied a pressure bandage. She complained of a splitting headache – and I worried about concussion. Clearly she had been knocked out briefly when she had fallen, striking the tip of her chin on the hard kerbside. I gave her as much pain relief as I dared.

‘I think I want to go home’ she said to me later. Understandably, she had lost enthusiasm for her horse trek.

‘Wait until the morning before deciding anything like that’ I replied. I know my wife. She bounces back and is no shrinking violet. I hadn’t the slightest doubt that she would change her mind.

In the morning she felt much better. There was no more talk of returning home. By then I had spoken to the leader of her trip over the phone. As luck would have it there was a nurse in the party who would be able to take her sutures out five days later.

We visited a safer bit of Buenos Aires. It was my wife’s 56th birthday – and we celebrated by having lunch Argentinean style, at a ‘Parilla’. She managed to look glamorous, despite the blood-stained dressing applied to her chin. After that we did the tourist thing and went to the Zoo.

The following morning we bade each other tearful farewell – and caught our respective flights. And two days later I am taking my first step into the Aconcagua National Park, by the Guardaparques office, at the start of the Vacas Valley…

Punta de Vacas to Pampas Lenas – 3rd February.

I feel elation as I step into the park. It has been such a long journey to get here – and I can’t believe I am finally here. My permit has been signed and stamped in the Guardaparques portacabin close to the road. I snap a quick self portrait of myself standing by the park entrance sign – standing proud in my Hepatitis C Trust t-shirt. Then I am off – striding into the valley towards a distant tiny spinney of poplar trees, which are about the only bits of green in the otherwise arid wilderness.

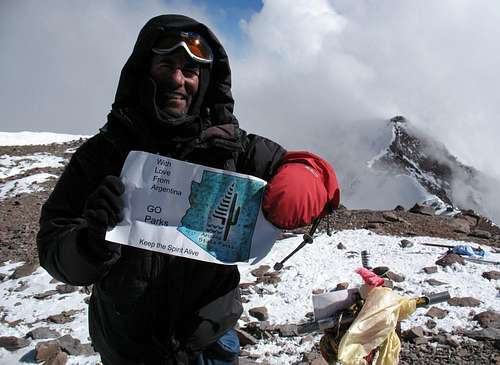

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() I snap a quick self portrait of myself standing by the park entrance sign

I snap a quick self portrait of myself standing by the park entrance sign

The winds are howling out of the valley, blowing clouds of dust, which I don’t want to inhale. So I have pulled up my buff into a face mask, which filters the gritty stuff. With my new pair of Aconcagua grade sunglasses I must look like some kind of alien.

I reach the trees and for a little while, I am walking between grassy meadows, with even a few cows on the other side of the raging brownish waters of the river. But this doesn’t last for long. I pass the last tree and around me the terrain becomes progressively more arid.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() A passing lizard

A passing lizard![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Last sighting of a tree for 3 weeks

Last sighting of a tree for 3 weeks

Despite the still howling winds, it is very hot under a furnace of a sun. Shade is scarce – but occasionally I find a large enough boulder to shelter behind, to pause and lighten my load of water. I have seen numerous lizards sunning themselves – and one pauses on a rock close to me. I snap a quick photo.

The trail follows an undulating course, up and down over alluvial fans or round interlocking spurs dropping from scree covered mountainside. The hours pass with the aid of the crystal notes flowing out of my iPod – which just manages to compete with the roar of the wind, albeit probably to the detriment of my hearing.

Periodically I encounter little groups of people. Some going up, but a few striding briskly down – adventure nearly over and presumably in a hurry to get out to showers and slap up meals – to celebrate a safe return. The returning people have intent expressions on their faces and don’t seem to want to do more than nod a greeting. I wonder what stories they would have to tell. I wonder if I will look the same as them, three weeks from now, when I am leaving the park. And will I be elated, having reached the summit? Or will I be a bit deflated – having failed to summit on this my fourth stab at a big mountain?

A little later I have my first encounter with a Mule convoy. I have always thought of Mules as slow plodding beasts – and it has been a surprise to me to learn that they are supposed to cover the ground so much faster than trekkers. To the accompaniment of thundering hooves and billowing clouds of dust I soon discover why…

The mules are moving at a near gallop. Hastily I duck behind a bush – the only bit of cover within range. Hooves crash down inches away from my face as one brute seemingly ignores my bush and runs through it, trampling one of my walking poles in the process. I feel I have somehow landed in the middle of a cavalry charge and cower timidly, hoping it will soon be over. I consider jumping in the river…

With a last billowing of dust they are gone – and I carefully extricate myself from behind the rather battered looking bush. I inspect my walking pole – carbon fibre and equal to the task of resisting a plunging hoof – so no damage. But I make a mental note: don’t mess with Los Mulas.

This particular convoy was heading down. A little while later, I encounter another one going up – and warily get out of their path. These ones are moving more slowly and I have time to notice the Muleteer, riding one of them at the back. Then I notice the next Mule: he is carrying my two large kit-bags – one blue and the other yellow. From a safe distance I watch them pass and trot out of sight around a spur.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Los Mulas – middle one carrying my blue + yellow kit bags.

Los Mulas – middle one carrying my blue + yellow kit bags.I reach Pampas Lenas late afternoon. It is a wide flat dusty area, a little bit bigger than a football pitch and strewn with boulders. I pitch my tent on bare gravelly earth and secure it to a few rocks, inside a crude dry stone wall which forms a wind-brake. Next door to me is another ‘pitch’ and a couple of women are erecting a posh looking grey and orange tent there, under the direction of their guide. I come to know them as Martha, from the USA and the older of the two – perhaps in her early 40’s. And then there is Grace, from Canada, who is about 10 years younger. They are part of a guided party of six.

I am feeling tired and a little lethargic. I recognise that it is more than just approaching 5 hours of walking, battered by winds and broiled by the sun. I have ascended from 2400 to 2800m – 9,200ft, and I’m also slightly affected by altitude.

My MSR stove rapidly produces boiling water for soup, a brew and a freeze dried mountain house meal. By 8.45 pm the sun is setting and I am ready to get into the brand new state of the art Mountain Equipment sleeping bag – loaned me by a neighbour, who just so happens to be Mountain Equipments sale manager – and who climbed Aconcagua a decade ago. I am using a silk liner and just as I am ready to crawl inside I notice the state of my feet. They are black. Fine dust has penetrated through my trail shoes and socks – and has adhered tenaciously to my skin. Further investigation reveals the same dust has penetrated scree gaiters and leggings – and I am black up as far as my knees. I can’t go to bed with all that. It takes quarter of an hour of vigorous scrubbing with wet wipes to get into more presentable state.

I wonder how Leila is getting on. This was also the first day of her horse trek – en route from Argentina, across the Andes into Chile. I managed to speak to her on the phone from the hotel at Penitentes after an hour of trying, yesterday evening. She sounded jubilant, loving the ranch where she was staying – and having had a great day getting to know people and horses. She said her chin was sore, but tolerable – and yes, she said, she was keeping some tape over it. We both nagged each other about being careful… but the line was poor and Leila in the middle of a barbeque so we soon had to say our goodbyes.

Pampas Lenas to Casa Piedre - Friday 4th February.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Pampas Lenas early morning

Pampas Lenas early morningI set off at around 9am, when the valley is still in deep shade. After 25 minutes the trail leads to a bridge, crossing the Vacas River. The sun caught me up a little while later, so I stopped for a drink, a second breakfast – and a liberal dousing with sunblock. The backs of my hands burned yesterday – sunblock rubbed off by the straps of my walking poles. So today I put on light silk gloves, after slapping sunblock on everywhere else that is exposed.

I had intended to go easy with the pace today but the iPod puts paid to that. Spurred on by rousing music I am soon striding along – and I overtake a few groups who set off ahead of me.

The scenery is increasingly arid – what little plant life getting progressively thinner. But I still find it beautiful – the deep blue of the sky, contrasting with reds, browns, orange and even occasional yellow of the rocky hillsides. I am having a ball here – and the valley sides swim steadily past.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Arid scenary in Vacas valley

Arid scenary in Vacas valley ![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Mud cliffs in Vacas valley

Mud cliffs in Vacas valley

At last, some four hours out from Pampas Lenas I reach a widening in the valley – and there is a side valley off to the left, which I guess is the Relinquos Gorge. Eagerly I stride another few hundred meters – and there it is: my first view of Aconcagua. The music had just got to a dramatic climax and I stand there totally overwhelmed for a moment. She is so beautiful and I am so glad I made my approach from this side.

Despite long moments staring up at my future goal, I am first into Casa Piedra camp, half a kilometre further up the trail. It is at yet another windy spot in the valley – and I feel slightly guilty as I nab about the only sheltered camping spot. I check in with the Guardaparques – and there is another stamp on my climbing permit. Moments later my little orange tent is up – and stove roaring.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Casa Piedra Camp

Casa Piedra Camp![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() My first view of Aconcagua

My first view of Aconcagua

The altitude is 3200m now – 10,500ft. A quite respectable height by Alpine standards – but I am feeling fine. Only another 12,360ft to go! Groups start to straggle in from the trail. My neighbours are a Polish expedition this time. Martha and Grace are camped further away.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Aconcagua at sunset

Aconcagua at sunsetCasa Piedra to Plaza Argentina – Saturday 5th February.

It is still dark when I awake just before 7am. I am both excited and slightly apprehensive. On the one hand I am looking forward to getting into the Relinquos Gorge and then having a day with Aconcagua right there, getting closer every hour, as I inch towards base camp up at Plaza Argentina. But on the other hand this is going to be my first tough day, where I shall be testing my altitude wings properly, climbing up from 10,500ft to 13,800ft. I hope I shall be OK with that. Of course, in my Alpine ‘trial’ in 2009, I went higher – when I climbed to the top of Mont Blanc. But I haven’t slept a night so high since 1989 – and it is most likely to be tolerance of sleeping height that determines things so far as acclimatisation is concerned.

I am ready for the off by 8am. My Muleteer, Juan, has kindly agreed to let me ride one of his mules across the Rio Vacas. A few minutes later I am wondering if this was such a great idea as I follow him out across the wide stony valley bottom, my mount moving at a fast trot, verging on a canter. A few years ago, I failed miserably at this in Switzerland, on a holiday with my wife. Having taken Leila up the Monch, quite reasonably, she decided a little reciprocation was in order – and she took me out on horse-back. I completely failed to be able to get the rhythm right and follow her into a trot, so we had – for her – a tedious ride, plodding round, albeit with the magnificent back-drop of the mountain we had just climbed.

But Leila would be proud of me. Today I manage – albeit that I have no choice but to manage, since Juan is setting a cracking pace and leading my mule by the halter. In deference to my assumed ineptitude he also has my back pack on, as he rides nonchalantly atop his beast.

Without so much as breaking stride the two mules plunge straight across the first of several channels of fast flowing water. In just a few minutes we are through the last, some 1000 meters from the camp and ¾ of the way across the valley. A group of Americans is in the process of crossing and as I cautiously dismount I try to ask what the going rate is for a tip, for the service Juan has just provided me. ‘We don’t know’ was the helpful reply. Juan is looking expectant and I rummage in my wallet, find a note and give it him. He looks extremely pleased – later I realise why – I just gave him a fifty note, thinking it was pesos (so about £7.50), but it was actually a US $50, so four times what I intended.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Juan heads back to Casa Piedra fifty dollars richer

Juan heads back to Casa Piedra fifty dollars richerBy the time I have sorted myself out the Americans are nearly a kilometre away and Juan and his mules long gone, back to Casa Piedra. So there is just me and my backpack, standing alone in the bottom of the still sunless Vacas Valley. I sling my pack on my back, settle my iPod ear-pieces comfortably, grip my two walking poles and stride towards the shadowy cleft of the Relinchos Gorge. This close, I cannot see Aconcagua, but I am full of joyous anticipation, because I know I will soon.

Soon I am in the gorge, scrambling up a narrow track that climbs higher and higher above the river, on steep shaley slopes. There is the occasional bit where I have to be careful: where a slip would result in a damaging or even lethal tumble, down into the river - anything up to 200 feet below. I wouldn’t fancy a face off with a mule here – and I’m relieved that their route is mostly on the other side.

Sooner than I expected I am greeted by the glorious sight of the top of Aconcagua, bathed in golden sunlight – high in the sky, way above the dark shadows of the gorge. Another half an hour or so and I too am now bathed in sunlight, as the sun climbs higher overhead. I reach a steep slope, where the trail ascends in a series of sandy switch backs. The mule route joins here – and just at that moment Juan returns with the cavalry, now heavily laden. And there is my mule with the yellow and blue kit-bags, right at the front. I get well clear and they all go thundering past. I am pleased to have got them ahead of me as I commit to the steep climb and its narrow paths.

It is slightly breathless work surmounting the steep slope, but worth the effort. For at a level area at the top, there is Lady Aconcagua in all her glory – completely exposed from base to summit. I can’t believe I have the audacity to try to ascend her shining flanks. There is the sweep of the Polish Glacier, ascending more steeply than in photos I have seen. It looks intimidating and I recognise from some discoloration, that most of it is sheet ice – as people have been saying. Well, I shan’t be trying to climb that! So it’ll have to be Falso Polaco – the Polish Traverse, from the foot of the glacier and round to join the normal route, round out of sight. But even that looks dizzyingly steep so far as I can see, as it wends its way round rock formations way up there, in the sky.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Lady Aconcagua in all her glory – completely exposed from base to summit

Lady Aconcagua in all her glory – completely exposed from base to summit![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Early morning in Relinquos Gorge

Early morning in Relinquos GorgeI catch up with the American group on the other side of the flat area, where they are removing their boots to cross the river. It is just ankle deep and not very fast flowing at this time of day and we are all soon across, re-tying boot and trail shoe laces on the other side.

Over the next few hours I play leap-frog with the Americans as we launch out into the wide open spaces of the valley beyond. It is my first real taste of big-mountain scale for decades. The distances seem vast and it seems to take an immense amount of time to make any progress. At some point I catch up with the Americans again, at yet another view point. The stunning vista has made them excited – and they include me in their chatter. They have an altimeter to hand. It is reading close to 3700m or a little over 12,000ft. So there is still around 500m height gain to go…

The hours and distance slide slowly past. Just three days out from the start I feel as if I have known no other life, striding though the dust, under a broiling sun. As I pass more into the afternoon I am aware that my pace is slower and I am more short of breath. I must be over 4000m – over 13,000ft. Two of the summits I climbed in Switzerland in 2009, were as high as I am now (see ‘Alps 2009: sunny Saas summits and a single return to Mont Blanc). On both of those I was up above the clouds and felt I was at the roof of the world… but I haven’t even reached the base of Aconcagua, towering above me.

The shining spire 10,000ft above my head is intermittently lost behind swirls of afternoon cloud build up. These curtains of mist are not that high and I realise it should still be clear on top. And by the looks of it, not much wind. I think to myself: people have probably summited today! I hardly dare think into the weeks ahead – and the remote possibility that maybe my turn will come…

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() The shining spire 10,000ft above my head is intermittently lost behind swirls of afternoon cloud build up.

The shining spire 10,000ft above my head is intermittently lost behind swirls of afternoon cloud build up.Some six and a half hours out from Casa Piedra I find myself facing the final obstacle between me and Base Camp. I know that Plaza Argentina is just a few hundred meters away, on top of a low mound of glacial rubble. But between me and it is the most extraordinary looking river – and somehow I have to get across it. The heat of the day has melted glacial ice and swept away tons of the dust and filth that the glacier bull-dozers dig up. Now this river has taken on the appearance of several channels of fast flowing rich brown chocolate fondue. If I so much as stick a toe in it my already dust ridden trail shoes will be clogged with the stuff. Then on the other side it will be like rolling a wet object in flour – and I will pick up a thick layer of reddish brown dust. And I don’t want to take off my shoes and paddle through it either.

The problem is eventually solved when I find a place with a few stepping stones. They are a bit widely spaced so I modify things a bit by hunting down some rocks – which I toss into the filthy torrent, to plug the gaps. Moving briskly, poles splayed out for balance, I launch myself at my doctored crossing and tiptoe across to the other side. I have to repeat the exercise with another couple of channels before I am completely across and relatively un-spattered with the liquid mud.

Ten minutes later I am standing at the edge of Plaza Argentina. All the times I looked at the pictures of this place – and finally, I really am here! But it is hardly a beauty spot. Before me is a level-ish area of glacier, strewn with mounds of rubble. No ice is visible. Somehow in amongst it all are little clusters of tents, large and small. You can see the place is divided up into sort of villages, according to Travel Company. Right in front of me is the Fernando Grajales village, off to the right Daniel Lopez. I search in the distance, several hundred meters off – and they are: the big red and white domes of the Inka tents – my final destination.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Plaza Argentina – Inka tents in the distance

Plaza Argentina – Inka tents in the distance

I make it half way through the Grajales encampment, when I am surprised to be addressed.

‘Hey – you must be Mark!’

I turn round and there before me is a small trim man, face half concealed behind big sunglasses, thick sunblock and a hat. I do a quick double take and then I know who it is. It is ‘Hazman2’ a.k.a Tom V, who I met on-line through Summit Post, just before leaving the UK. Tom read in one of my postings that I would be arriving today – the day after his own arrival, from Colorado. He is also a solo climber, but had suggested we look out for each other.

He is similar age to me – just a couple of years younger. He is very much a man of the mountains and was climbing 4000m peaks just a week before coming here. He has unfinished business with Lady A, having been denied the summit by bad weather, back in 1997. He had got up as far as Campo Berlin, from the other side.

It is pleasant chatting to Tom and he is hinting that we could maybe join up, at least on a trip up to Camp 1. Quietly I am slightly apprehensive of this. Tom looks so fit – and acclimatised to the Colorado summits, he took just four hours to get up here from Casa Piedra. I took nearly seven – albeit still within ‘guidebook’ time. And Tom has already had a foray up to Camp 1 – today, just the day after his arrival. He is planning on a rest day tomorrow – when I plan a rest day. So it looks as if we would both be going up to Camp 1 the following day, Tom to stay and me just to ferry a load before returning to Base.

We agree to look each other up and then I head off in the direction of the Inka tents. I had paid for their ‘climber assist’ service, principally concerned with having all my travel and transfers as far as Plaza Argentina covered. I was vaguely aware of something else in the package to do with meals at Base Camp, but hadn’t really taken much heed. So I am surprised to be welcomed by a little team of people – and promptly plied with jugs of juice in addition to plates of cold cuts, cheese and biscuits. It is around 4pm in the afternoon – and I am told dinner will be served at around 7.30pm.

I pitch my vintage blue gortex Gemini tent close to the Inka village. It is 24 years old and leaks like a sieve if it rains. But it is still sturdy enough (I hope) to withstand the winds reputed to blow here – and I believe at this elevation it will be snow rather than rain, if there is precipitation.

Carries to Camp One 7-13 February.

After a rest day at Plaza Argentina, enjoying unexpected comforts courtesy of Inka, I finally set foot on Aconcagua. Yesterday was windy and cloudy, but today is bright and clear – the serried ramparts of mighty Ameghino glowing golden in the early morning light. It isn’t possible to see the far higher peak of Aconcagua from here since a big buttress is in the way, so Ameghino is the highest mountain in view, at 19,300ft. As I exit my little blue tent I note that it is cold – and the thermometer is saying minus three centigrade. I enjoy an Inka breakfast, courtesy of Adriel and Sabrina.

I am determined to get the acclimatisation thing right on Aconcagua. With this in mind I have divided things up such that I will do three carries to Camp One, rather than the two that many, including Tom, do. This will enable me to carry lighter loads for a start – a factor since I am an old bugger now, and I do get back ache. Today I am carrying mainly food and a pair of litre and a half bottles of white gas fuel. On top of this are my two water bottles and a little bag full of nuts, chocolate and energy bars – my own fuel for the day.

Excited again and full of anticipation I set foot on the moraine slopes leading up out of the camp. Although at close to 14,000ft I feel OK and ready to climb higher than Mont Blanc, for the first time in 22 years. It is around 9.30am – and Tom said he would be setting out at a similar time.

A couple of hundred feet above camp I stop to get the iPod going and snap a couple of photos – and like a spritely looking tortoise, literally with his house on his back, up he pops, from the direction of the Grajales camp. His back pack is enormous… ‘It sucks!’ he informs me when I enquire, full of concern. But big load or not, I still think Tom may leave me behind with his obvious fitness and acclimatisation.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Tom with the load that sucks…

Tom with the load that sucks…

But he doesn’t. Clearly the big load is taking its toll. We end up walking together in companionable iPod silence. We are still scrambling up moraine but progressively being driven into a narrow ablation gulley with the, now frozen, stream in the bottom. To the right is the side of the glacier – a great wall of dirty ice, partly undercut by the stream. To the left are steep slopes of bouldery lateral moraine. I can see that there is quite a danger of stonefall and even landslides from these slopes and I’m aware there have been accidents here, including fatalities. I should really unplug my iPod headphones, the better to hear anything tumbling down. But it is all well frozen still, so I don’t – nevertheless I make a mental note to heighten my vigilance coming down, when all is warmer.

After an hour of walking and scrambling we emerge from the danger area into a wide level looking glacial amphitheatre, affectionately known as the ‘bomb site’. It isn’t really level, but gains several hundred feet in height as we look across in the direction we have to go. As for the bomb reference, it does look as if it has fallen foul of a squadron of B52’s – all churned up rubble and great craters, as often as not containing a frozen pond at the bottom.

The top part of Lady A is visible again, looking up to the left, above where a hanging glacier plunges precipitously down towards us, in a complex looking ice-fall. I snap another one of several pictures of Tom against this spectacular back drop.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Across the bomb site towards the final pull up to Camp 1

Across the bomb site towards the final pull up to Camp 1![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() The top part of Lady A is visible again

The top part of Lady A is visible again

We pause for a drink and a chat at the periphery of this vast churned up area. Tom points across to the final ascent to Camp 1, across the other side of the bomb site and about a mile distant. There is an abrupt wall of steep scree about 1000 feet high, split into a lower 1/3 of more gentle slope, but then an upper 2/3 which rears up steeply – sandwiched between a huge buttress and a great slope of penitentes, the weird snow columns that form in these parts due to the combination of wind and sun. He points out a faint track which starts from the bottom of the left hand end of the steep section and then angles across in rising traverse to the right, before turning to head straight up in a series of steep zig-zags up into a shallow gulley up near the top.

He tells me that the scree sucks like his back pack, but that getting onto that rising traverse makes at least half of it easier.

I am a little apprehensive of this formidable looking upper slope – which starts at about the height of Mont Blanc, at about 4800m. Knowing that I will find it a struggle, this first time up here, I warn Tom I shall be slower than him – and to just go on without me if that is the case.

An hour later, we are stopped again at a little level area near the bottom of the slope. There is a little penitentes field close by as well as the much bigger slope several hundred yards to the right. I look across curiously, not having seen penitentes before. Tom starts off again. I take my time setting off – and am at pains to select the most arousing bit of my current favourite iPod playlist. This turns out to be simultaneously my saviour and my downfall, since captivated by the music I miss the turning up to the rising traverse and find myself blundering up horrible steep loose scree at the side of the big penitentes slope. Looking upwards and to the left I can see Tom gaining height with easy strides as he walks up the rising path.

It would be too time consuming to rectify my error by turning back – so I grit my teeth and plough on straight upwards, sliding a half step backwards for every full step upwards. Soon I am panting hoarsely in the thinning air.

Eventually and after something of a struggle, I reach the top end of the rising traverse – just as it turns upwards into the zigzag section. From my perspective this is just more unstable scree, having completely missed the easier section of the route. Tom is somewhere above, lost to sight since he has dipped into the gulley up at the top.

I plough on, struggling a bit, but also feeling the satisfaction of knowing that every step up now is taking me higher than Mont Blanc. At some point I think that I must have got to over 16,000ft. Sometime after that I enter the gulley, which is both steep and looser than ever – with a small stream at the bottom. But I keep going, stopping to pant briefly every few dozen steps, whilst leaning on my poles.

Quite abruptly I pop out of the top of the gulley. There is a small plateau and then a small rise – and I can see that Camp 1 is just on top of the rise. In another five minutes I am there, shrugging my rucksack off, alongside Tom – who is just putting the finishing touches to his tent. It has taken me four hours to get here. He took three and a half.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Camped beside Tom at Camp 1

Camped beside Tom at Camp 1![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Camp 1, devoid of snow - before the storm

Camp 1, devoid of snow - before the storm

I feel a sense of achievement. I’m at 5000m – 16,400ft. Camp One is at the bottom of a hanging valley which rises up steeply to a col at 17,500ft, between Ameghino and Aconcagua. It doesn’t feel that high – especially as the whole area all the way up there is practically devoid of snow. It could be a high corrie in Scotland – at 2000ft. Later I walk to the edge of a sharp drop off, down onto the steep scree slope we have just laboured up. There is a bit more of a sense of height from there. Base camp is out of sight – but it is possible to see most of the Relinquos Gorge leading down to Casa Piedra, 6000ff below and far in the distance.

I spend over an hour chatting to Tom, before I cache my load, placing all that I am leaving in a Mountain Equipment holdall, which I bury under a small cairn. I wish him good luck for his first night up here, and then I shoulder my near empty rucksack and head for the top of the gulley. I am in my element going down, taking great strides down the steep scree. It takes just an hour and a half to return to Base Camp.

That night the Inka team surpass even themselves. It is a proper marinated Argentina steak plus fried potato slices for dinner!

Next day I pack up my little orange tent plus a few other bits and pieces and set off for Camp 1 again around 10am. The weather isn’t so good. There was some light snow during the night and slopes have a frosted look. It takes me only 3 ½ hours to get up there today – although I seem to find it just as hard work. I do get the route right this time though – and appreciate the ease of the rising traverse across the steep upper slope.

There are a few tents scattered around at Camp 1. Tom’s tent is all sealed up and he is nowhere to be seen. Heavy dark looking clouds are swirling round, so without further ado I break out my tent and erect it swiftly – tying it down to as heavy rocks as I can find. Conveniently there is a partially completed stone wall round the site I’ve picked, alongside Tom’s. I add a few rocks to it, to finish it off. I just have time to throw all that is staying up here inside the tent when it starts to snow.

Tom appears at that moment. His face is puffy with great bags under his eyes in deference to his first night at altitude – and he has also carried a load up to Camp 2, up at 18,000ft.

This is the first time I have heard of the particular Camp 2, which Tom is using. It is actually Camp 3 of the ‘Guanacos route’. Reaching it entails getting to the Ameghino col, then instead of turning left up steep scree to the Polish Camp 2 – at the higher elevation of 19,000ft: the route traverses round and upwards towards the mid section of the ‘Normal’ route, up from Plaza de Mulas. From this Camp 2, Tom plans to climb up to a Camp 3, called rather worryingly Cólera Camp, up at 19,500ft – very close to Berlin Camp, the normal springboard for the summit – and where he was forced to turn back in 1997.

One of the reasons he is going the Guanacos way is because he has organised things so he can descend to Plaza de Mulas and the shorter walk out from there.

We share a brew and then bid each other farewell and good luck. When I come back up tomorrow he will have moved up to his Camp 2, up at Guanacos 3. Short of unforeseen circumstances we won’t meet again. It is now Tuesday and Tom hopes he will have summited by Sunday… weather permitting – and the weather isn’t looking great just now. We plan to communicate via Summit Post again, on our respective returns.

Once again I am back down at Base Camp in an hour and a half.

Back down at Base I head over to the Daniel Lopez tents, where I’ve been told there is internet access via satellite link – at a price! There is – on the tiniest lap-top I have ever seen. Squinting at the miniature keys, I access my personal e-mail account to find a cluster of mailings from friends and work colleagues, wishing me well. The connection is too slow to be able to reply to them – but I put together a quick message, which I send out to all.

I have my last Inka meal that night. The plan is to go up to Camp 1 for the last time tomorrow – and to stay up there. I don’t plan to come down until after my summit attempt, whenever that will be.

The Storm 9th-12th February

The weather looks quite threatening next morning, but not actually snowing. I pack up the blue tent, my little orange one being already erected up at Camp 1. Inka’s satellite connection is working today so I use it to leave messages for Leila. I think this is the last time I will be at Base Camp until after it is over.

The weather forecast is not very good for the next three days – but winds are predicted to be light and with only moderate precipitation, so I think it is still worth going up. If conditions aren’t too bad, I hope to be able to at least carry a load up to Camp 2 on the Polish route. Then when the weather improves, I shall be in a position to have a go at the top part of the mountain.

I set out in just my thermals and move at reasonable speed up the moraines, through the dangerous ablation valley and up into the bomb site. An hour out from base I stop for a rest – and exchange pleasantries with a tough young Argentinean Porter carrying a monster load. Just before I start off again, the first few flakes of snow begin to fall. It isn’t that cold, so I just pull out my Gortex jacket and salopettes – and put them on over my thermals, anticipating getting hot as I climb the steep scree again.

With a far lighter load, I draw slowly ahead of the young Porter. I start up the steep scree slope for the third and I hope, last time. Visibility is deteriorating steadily and the snowfall getting heavier. I am glad my tent is already erected up above…

The wind picks up. Soon there is a howling gale blowing. In just thin gloves my fingers start to chill – as do the rest of me. With about 300 feet of ascent to go I am in a full scale blizzard. I pull my buff up to cover as much of my face as I can. It is getting hard to see with my sunglasses fogging up as well as becoming covered with spindrift. The scree is becoming plastered with the stuff, wherever there are nooks and crannies. It is hard enough battling up here at the best of times, but now, straight into the teeth of the gale, it is bordering on impossible. I keep slipping and it is a real struggle to get back up.

I am getting quite cold. The sensible thing may be to stop and pull on some warmer clothes, but I decide that I am close enough to Camp 1 to just go for it – and trust that I will be able to hurl myself into the tent in time to warm up in there.

As I finally crest the top of the gulley and come level with the plateau, the wind is even more vicious, speeded up by the venturi effect as it hurtles through the narrowing there. The stream is here. Most of it is now frozen but I find a little trickle somewhere and cursing at what it is doing to my fingers, I top up my two water bottles – in anticipation of not wanting to step out of the tent, once I have got inside it.

I worry briefly about the young Argentinean Porter, who is somewhere behind me, slowly battling up the scree. Through the stinging clouds of spindrift I can just see him about 200ft below. His hunched shape is moving albeit slowly. I am sure he will be OK. He is a big strong young man and had on more clothing than me when I last looked. But I won’t be OK if I hang about here any longer. Barely able to see I stagger across the plateau, my now frozen fingers clutching the two water bottles. I reach the top of the little rise and there ahead, looking almost ghostly with the fog of spindrift blasting past, is my tent. For a moment I think Tom is still here. There is a tent in his spot, but then I realise it is yellow and grey, when Tom’s was a uniform yellow.

I am about to realise the disadvantages of going ultra light with a tent. I made a conscious decision to have a tent with no vestibule. Thus when I open it, I will immediately expose the interior to the storm. I won’t be able to stop copious snow and spindrift whipping inside – in addition to all the snow all over my boots, clothing and rucksack. Beginning to shiver now, I don’t hesitate and wrestle the partially frozen zips until I have an opening large enough to hurl in my pack followed by myself.

As I feared, by the time I have wrestled the zips back, the inside of the tent is a winter wonderland, snow all over everything. Once I have struggled out of my boots and gortex and put on some warm layers, I spend 20 minutes with a little brush, carefully collecting the snow into little heaps, prior to shoving as much as I can out through a slit I unzip round the door.

I warm up reasonably quickly – apart from my toes, which take an age to stop tingling and hurting. The tent flexes and shakes under the onslaught of the wind. I am thankful that I took the time to enlarge the bit of dry stone wall that encloses my pitch. I am also thankful that not entirely trustful of the forecast of light winds, I also took the time to weight the tent down with rocks inside as well as out.

My next concern is I need food and drink. This means using the stove – and the instructions that came with it say in bold print how bad an idea MSR think lighting it inside a tent is. The only other time I used it inside this tent was when subject to a severe midge attack in Scotland (see ‘Scottish Highlands 2010: of vampires, mountains and men’). But there was no wind then and the tent nice and still – and I could have all ventilation ports open, protected from the tiny vampires by fine mosquito mesh. Whilst the mesh was fine enough to stop swarms of the tiny insects getting in, the same couldn’t be said for spindrift. If I just so much open a ventilation port a chink, then clouds of fine snow dust are driven in.

But a couple of hours later, I decide I have no choice. I have to be able to use the stove. Spin drift and all I open the two ventilation ports and drop the inner door down a couple of inches, leaving the outer mosquito net one up. I try to ignore the cold dust spraying in my face. I roll my sleeping mat and bag up from the front end of the tent and sit on it. Finally I place the MSR stove between my legs and very cautiously go through the ritual of lighting it. It splutters into life – but not with the 747 jet engine roar it makes at lower altitude. The next annoyance is that I discover that the water I collected from the stream is now almost frozen in the 2 bottles. I have to go through a complex process of heating what is still liquid, tipping it back in to a bottle to thaw some of the ice – and repeating the exercise over and over until both bottles are part full with warm liquid - and I have a pan of boiling water on top of the stove. Only then can I turn it off.

Yet another annoyance is that I discover that I have no taste for the predominantly savoury high altitude food I have brought up. I liked it 13,000ft lower down, in Scotland. But up here I find the soup unappetizing and as for my favorite ‘Spaghetti Bolognaise’ it is as unappealing as wallpaper paste. I force it down with difficulty.

Next morning is Thursday 10th February: the last day of Leila’s horse trek. I do hope she is OK and hasn’t fallen off one of the brutes. But I will have no means of finding out until I am down off this mountain.

It seems to have snowed all night and I can see from the tent walls that I am partially buried. Thank heavens for the pee bottle. Actually, considering the altitude, I passed a remarkably OK night. Having been troubled with Cheyn Stokes (‘periodic’) breathing mildly down at Plaza Argentina I resolved to take a half a Diamox at night at higher camps – and up here, it seems to have worked.

At 8am there is a respite in the storm. The winds persist, but some sun breaks through tattered streamers of cloud hurtling across the sky – and it is no longer snowing. I burrow out of my snowed up tent like a mole – pushing aside the drift burying the tent entrance. I find out I am camped amidst the guided group which includes Martha and Grace, who camped beside me way back at Pampas Lenas. They are camped just across from me and their guide Martin (plus assistant) is in the now partially buried yellow and grey tent next to me, where Tom had camped. I meet other members of their party, Fernando and Pedro – and later a young Englishman called Ian.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() My new neighbour at Camp 1.

My new neighbour at Camp 1.![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() First morning at camp 1

First morning at camp 1

Martin tells me they are pressing on with the Polish route. That day, despite the conditions, he is going to take them on a load carry to Polish Camp 2, up at 19,000ft. It looks pretty dire up there, but I assume he knows what he is doing. The sky is now nearly clear, but billowing clouds of spindrift are blowing off the col and it is clear that the dreaded ‘Viento Blanco’ is howling up there.

Other tents are dotted around, but most occupants are hunkered down and the wind and still occasional lashing clouds of spindrift are no incentive for straying far to make house-calls.

I watch Martins party ready themselves and shoulder their loads, and set off towards the Ameghino col, over 1000ft above.

A few others emerge from tents eventually. I get to meet another guide who unlike Martin is not enthused by the Polish route in these conditions. He seems to feel that both the Polish Camp 2 – and 3, across the traverse, are unacceptably exposed. And the traverse may well be plastered in new snow – hard work to slog through at approaching 20,000ft. In addition he points out how big a jump in altitude it is from this camp to the next – especially when the entire route as well as the camps, are fully exposed to the elements. Again, all the more exhausting in these conditions. This guide is going to take his party the same route Tom took – go for the lower Camp 2 (‘Guanacos 3’) followed by a slightly higher Camp 3, at ‘Cólera’ Camp – which is the nearest of the high camps to the summit.

I start to think that I am going to change my plans and go that way myself. But I will also see what kind of state Martin’s party are in when they return.

The weather is slowly deteriorating again, but I don’t think my lumbar spine will tolerate being scrunched up in the tent again straight away. I make the most of a brief opportunity to cook outside, in the space I excavated in the deep drift in front of the tent. Collecting water from the little stream now involves digging a hole through the frozen surface with an ice axe and once again I freeze my fingers collecting from the tiny trickle I find. I fill up the pair of litre bottles and also a big two litre container. Having learned my lesson the day before as regards how quickly water freezes on exiting the stream, I get it warmed up on the stove as quickly as possible.

I take the opportunity to visit the Camp 1 ‘banos’. It is simply a crude shelter – a little alcove of tent material, almost perched at the edge of the drop off down to the big scree slope below. As such it has a terrific outlook, albeit in these winds it stands a distinct chance of disappearing into same outlook, should its anchoring fail. A strict rule on the mountain is that you take everything you ‘do’ on the mountain down, for proper disposal. So some kind person has left newspaper, upon which to collect your specimen, before (it is recommended) double bagging it for transport.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Looking down towards Base Camp from Camp 1 ‘banos’

Looking down towards Base Camp from Camp 1 ‘banos’

From time to time I glance up at two parties inching up the bright white slopes to the col. They are moving incredibly slowly. Aside from the altitude, I expect they have to trail break through deep snow. It is bizarre to think that these same slopes were all bare scree a scant few days ago. I wonder how Tom is faring up at Camp 2.

By 1pm clouds are starting to build up again. I make the decision to make lunch the main meal of the day, given the likelihood that conditions will be reverting back to how it was yesterday afternoon. I have a pint of asparagus soup followed by a chicken curry – which is more tolerable than yesterday’s spag-bol, but I still wish I’d brought more sweet meals. After lunch I sort out a load for carrying up to Camp 2 tomorrow – wherever it is going to be… Guanacos or Polish?

By 3pm the snow and winds are back at lower levels and I am driven back into my tent. Grace, Martha, Ian & Co with Martin the guide don’t return until very much later, by which time it is blizzard conditions again as well as nearly dark. I want to hear how things went but it is too noisy to shout out to them and try to have a conversation. And I am too warm in my sleeping bag to go through the ritual of getting up and out – and still worse, coming back in along with a load of blown snow.

Next morning is Friday 11th. After another stormy night, I get out to find Martha and Ian also up and about. They tell me they made Polish Camp 2, but as anticipated, it was exposed to wind all the way up – and pretty dire at the camp. Martha has had enough and is going down just as soon as Martin can arrange for her to be accompanied by their porter. The rest of the party are going to rest up today, but plan to go back up to Camp 2 to stay tomorrow night. A bit later I speak to Grace. Of all of their party she seems to be going the strongest, but not unreasonably she seems uncomfortable with the fact that they are now committed to the Polish route, with the exposed camps and long traverse high up on the mountain.

None of us know that today two groups are getting poised to make summit attempts tomorrow. On the Polish route, there is a group of three – from Poland as it happens. Round the other side of the mountain, there is a larger guided party which I shall call the ‘Anglo-Australian’ group. This latter party has somehow, despite the storm, reached Cólera camp – and they are currently hunkered down and also waiting for a chance tomorrow – which is Saturday.

The weather forecast I had obtained before I left Base Camp, had predicted that conditions should be fine on Saturday. However the same forecast had also predicted that there would only be light winds and precipitation for the last two days – and ‘clearing’ today. Clearly this forecast was way off the mark – and from the look of things it is definitely not ‘clearing’ today.

There is not the relatively calm start to the day that there was yesterday. There will be no preparing breakfast and lunch sat outside the tent. My lumbar spine won’t tolerate being confined to the tent all day, so I make the decision to try to walk up to the Col. I don’t intend to go further, but just to reconnoitre the next part of the route to the Guanacos Camp 2. I won’t even try to do a load carry and will travel light, just with water, energy bars and camera.

I wrap up warm and set off after a large party plus two pairs, who are amazingly also venturing out in this. Very slowly I catch up the large party and, lightly laden, end up out in front – where I play leap frog with one of the pairs. When I stop and rest they overtake and then when they stop, I overtake – etc. But it is very hard work when out in front. The tracks made yesterday are all filled in and so it is a matter of breaking trail, in snow anything up to mid calf deep.

As we approach the col conditions are progressively worsening. The sky is partly clear but great clouds of spindrift are blowing in our faces.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Violent conditions just below col

Violent conditions just below col![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() As I approach the col conditions are progressively worsening

As I approach the col conditions are progressively worsening

By the time we reach the col, it is how I would imagine it to be in a wind tunnel. Vicious winds are shrieking round the rocks. The winds have scoured out a great curved wall of snow, which diverts the blast round and into the back of the one rock buttress which seems as if it should offer shelter – so that there actually is no shelter anywhere.

Leaning hard into the icy blast, I inch my way over bare frozen rocks between the snow wall and the rock buttress. I make it out the other side and up a short rise on to the col itself. It is a bleak and miserable place. Incredibly I spot three tents up there and through clouds of hurtling spindrift I see three figures struggling to erect a forth. Much closer and partially buried under some drift, I see signs of a trail heading across the col and bearing towards the left. That must be the route up to the Guanacos Camp. Bearing steeply upwards as well as sharp left is another trail – that must go to the Polish Camp. It looks desperate up there.

I have seen what I came to see and turn back. Back down through the ‘gun-barrel’ I see the large party, still on their way up. I don’t know where they are headed. It is too noisy here to ask. But I hope they are going for the Guanacos route.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() View from col down to Camp 1

View from col down to Camp 1![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() The curved wall of snow created by the winds at the col

The curved wall of snow created by the winds at the col

I am back down at my tent inside 40 minutes. In the blizzard that is now blowing it is once again, a miserable performance getting back into the tent and half the snow on the mountain follows me in. Conditions are so violent, that I daren’t take the risk of operating the stove. I make do with the remains of this morning’s water and a bar of chocolate. I have to spend quarter of an hour painstakingly sweeping up all the snow inside the tent.

Next morning it is a bit clearer again – snatches of blue sky between the racing streamers of cloud and spindrift. But the winds are as strong as ever. Dehydrated I decide I must risk lighting the stove, but first I have to brave collecting water from the stream. Once again it is vile, crouching down whilst being lashed by the gale and trying to fill my containers from the pitiful sub zero trickle exposed by my ice axe.

Somewhat later I emerge from my tent dragging out my loaded rucksack. Despite the conditions I am going to try to reach the col again – and then follow the trail up to Camp 2, if I can. But I know there is a good chance I won’t be able to get there.

It is even worse getting up to the col than yesterday. The light is bad and I am glad I put on clear ‘bio-hazard’ safety glasses to protect my eyes. Spindrift is being blasted along by winds of probably over 60mph – and a glance at the little thermometer hanging off my back pack reveals the temperature is minus 15. I hate to think what the wind chill is. Despite a full face mask, my nose is beginning to freeze. At the col I encounter Martin the Guide and his party (minus Martha) all trying to shelter behind the rock buttress – which isn’t a shelter at all. They are being lashed with stinging spindrift and all look miserable crouched there.

I wonder how on earth they think that they are going to get up to Polish Camp 2 today. But they don’t now apparently – Martin shouts above the wind that they are going to turn back.

Camp 2 (Guanacos 3) is easier to reach, so I continue up to the col again. Through the driving clouds of spindrift I see that the three I saw here yesterday did manage to pitch their fourth tent. How any of them are still standing is beyond my comprehension. I put my head down and stagger over bare rocks, where I can just discern the trail leading to my destination. It is said to be an hour and a half distant from here. I don’t really rate my chances of getting there.

After 100 meters the trail disappears under a layer of windblown snow. Clouds are swirling round and intermittently I am in white out. I plough on maybe another 100 yards, picking up snatches of trail between drifts. But then I notice that my boot prints, where there is snow, are being filled with spindrift virtually as fast as I am making them. I also notice that my nose has started to go numb.

I turn back – and once again am down back at Camp 1 in about 40 minutes. I still have my load for Camp 2 on my back. There was no where sheltered up there to cache it. I encounter Martha, the American lady from Martin’s party. She tells me that three others from their group have also had enough and are going to go down. So that just leaves Grace and Ian to stay up with Martin – and try to make a summit attempt, in the next 2-3 days.

Tragedies in the storm

Completely unknown to all of us at Camp 1, a tragic drama has been playing out higher up the mountain. I have managed to piece together what I know from various eye witness accounts, including from a member of one of two stricken parties – and from my own experience of conditions on the days the events happened.

From the timing of events I can only assume that the two parties believed the weather forecast which predicted a good day on Saturday 12th – since it appears they positioned themselves to make a summit bid that day.

The Polish group of three were following, coincidentally, the traverse route named after their country. They had got themselves up to Polish Camp 2, at around 19,000ft on Friday 11th. On the other side of the mountain, on the same day, a larger guided party I shall call the ‘Anglo-Australian’ group were up at Cólera, which they had reached the day before. There were nine in the Anglo-Aussie group.

On Saturday 12th, both groups set out for the summit. The Polish group would have a longer day ahead of them, with the 2-3 hours of the Polish traverse to do before getting onto the ‘normal’ route, which the Anglo-Australian group had set out on. Down at Camp 1, the weather appeared clearer than it had been first thing in the morning. Perhaps the skies were clearer still up at around 6000m, convincing the two parties that it was reasonable to set out. But although the skies were clearer, even down at Camp 1, the winds were still very strong. They must have been taking a hammering so much higher up.

The member of the Anglo-Aussie group I subsequently spoke to was a young man called Brad. He told me they kept moving upwards although the party was extremely slow. He said that at the speeds they were moving, in those conditions, he constantly fretted about frost-bite and wanted to move faster and get it over quicker. But the party was reduced to moving at the speed of the slowest members. At some point, the second guide in this party, a ‘local’ did turn back to Cólera Camp with at least one member of the team, who had had enough. Brad said that the local man had counselled that all should turn back in the conditions, but had been over-ruled by the senior guide – who wasn’t a local. Thus most of the rest of the party kept on going - and Brad informed me that they summited at the very late hour of 6pm.

Around the time of summiting, Brad said that the oldest member of the party, a man in his early sixties, began to get into difficulties. The party, led by their one remaining guide, set off down the mountain. Again, the speed was very slow and Brad said he continued to fret about the high risk of frost-bite.

Of the three Polish climbers, one was unhappy about the conditions and turned back. He got down unharmed. The other two pushed on but didn’t reach the summit. As they descended, they caught up with the Anglo-Aussie party a little below the Canaleta, on the long traverse across the Gran Acarreo, still up at well over 21,000ft (6400m). Brad said that with the onset of night and the savage conditions the two Poles made the extraordinary decision to go back UP. They said they would try to get back up to the place known as La Cueva (the ‘cave’) up at 6650m or at approaching 22,000ft – at the bottom of the Canaleta. Except that this place isn’t a cave, it is simply a ledge in the scree with a big and slightly overhanging rock buttress above it. It isn’t sheltered at all.

All that I know of the two Poles from here onwards is that one was subsequently rescued from somewhere high up. The other just disappeared. Over subsequent days a helicopter search of the upper part of mountain was unsuccessful – and the body, so far as I know, has not been found. Of the rescued man a squad of Guardaparques found him and short roped him down to Camp 1 – on Sunday 13th – and from where he was helicoptered out, severely frost-bitten. A witness at Camp 1 later told me he saw the man from a meter away and that his nose was black with frost-bite – and appeared to be having problems with his hands and feet. It is reasonable to assume both also were deeply injured by cold. The same witness, Zak R from Arizona, had seen the stricken Pole subsequently rescued by helicopter. This time from some distance away, he photographed the grim event. Two Guardaparques had to help the unfortunate man into the helicopter.

![Aconcagua 2011 TR]() Two Guardaparques had to help the unfortunate man into the helicopter

Two Guardaparques had to help the unfortunate man into the helicopter

To return to the previous day, Saturday 12th: Brad said that after they had seen the two Polish turn to go back up to La Cueva, his party carried on down. In complete darkness, they reached the Independencia ruin. Earlier their guide had radioed his colleague, down at Cólera, and having left his charge(s) there, this man climbed back up to meet the party at Independencia. By then the elderly Australian was in such a bad way that he was ‘talking nonsense’ – and clearly too ill to move further. The senior of the two guides would stay with him, but the local guide offered the remainder of the party the opportunity to descend back to Cólera camp with him.

Sadly, only Brad and one other elected to keep going to Cólera. The remaining four in the party felt they couldn’t go any further and decided to stay with the senior guide – and the elderly Australian – who by then was dying. They all huddled together inside the tiny ruined hut.

Independencia Hut is similar size and shape to a four man tent – of the outdated ‘ridge’ style. About a quarter of its wooden planks are missing – blown away by the ferocious winds that blow across the bleak little plateau on which it resides. All the missing planks are from the roof, so it is completely open at the top and quite a way down one of the sides. It provides next to no shelter.

Brad and the other member of the party, who wanted to descend, picked their way slowly downwards, in the charge of the local guide - who unsurprisingly had difficulty finding the way. But somehow he got them back down to Cólera, albeit not until after midnight. Nevertheless they escaped frostbite.

Up at Independencia, the elderly Australian slipped into a coma and died. The other four suffered deep frostbite to hands, feet and noses. After dawn the beleaguered four descended with the guide – who wasn’t frost bitten. The dead man was left inside the ruined hut – where he would remain until brought down on Wednesday 16th.

Brad didn’t say what time the rest of the party returned to Cólera. Conditions were still bad. The four with frostbite were all ‘in a bad way’. Brads tent mate was one of them and was ‘completely helpless’, needing assistance with all actions. With the weather conditions and the state of the injured four, it was impossible to descend from Cólera until after another two nights. So they would have descended on Monday 14th – when there was good weather again. But it would be a long hard day, getting all the way down to Nido de Condors, where the injured could be evacuated by helicopter. Brad and the other uninjured members of the group, plus the guides, all then descended to Plaza de Mulas.

At around this time there was a third death. I did not get to hear the details, other than that on Sunday 13th a 38 year old Czech man died at Camp Berlin.

The events described here are tragic and shocking. I do not attempt to cast any judgement, for it is not my place to do so. But the events serve to illustrate that whilst a technically easy mountain to climb by the standard routes, Aconcagua is a vast and complex mountain, subject to very savage conditions. To venture out high on the mountain in storm conditions is perilous indeed. And every year a number of tragedies illustrate this very point. Those who venture onto Aconcagua with the mindset ‘it is just a walk’ would do well to re-consider.

Return to Base Camp Sat 12th – Mon 14th

To return to my own story:

As I return to the storm lashed tents of Camp 1, beaten back from the col for the second time, I am not yet aware of the tragic events taking place much higher on the mountain. It doesn’t occur to me that anyone could be making summit attempts in the conditions as they are.

I encounter Martha, the American lady, from the group guided by Martin. She had already told me that she was going to go down as soon as their porter could accompany her. Now she tells me that three others have had enough and have decided to go down with her. This just leaves the young Englishman Ian, and the Canadian lady, Grace. Of the original party of six, just two are going to go and make a summit attempt. They are going to try to get up to Polish Camp 2 again tomorrow – and then try for the top from there. They are going to attempt to do the traverse and continue on, without putting in a Camp 3 at White Rocks.

I consider my options. I have been in the park as long as Martin’s party. They did reach 19,000ft on their trip up to Polish Camp 2, but I have been up to 17,500ft twice and overall I think our levels of acclimatisation will be similar. But for me, I think that a summit attempt on Monday, just the day after tomorrow, is too soon. On my schedule the earliest day for making a summit attempt is Thursday, three days later – or five days from now. There is just no need to keep battling these conditions.

My ‘little voice’ that I promised Leila I’d listen to, says clearly go down. All the way down – to Base Camp. Another voice says, but what if by doing that you miss out on a perfect summit day on Monday?

But the little voice says, well that would be just too bad. I am NOT ready yet. If I don’t get good conditions later in the week or at the weekend, then that also would be just too bad.

I start to pack a few things to go down: all the rubbish for example – and a bit of water. I still have the big two litre container of water that I painstakingly collected from the frozen stream this morning. I don’t need to take that. I think of poor Martin, in his tent next door to me. All through the storm he has been collecting water and cooking – for seven, eight including their porter! At intervals above the howl of the winds I have heard him bellowing to his party ‘Guys! GUYS! Hot water!’ He appreciates my extra two litres, delaying as it does his next grim trip down to the stream armed with ice axe and jerricans.

Within half an hour of making the decision I am ready to go. I am slightly apprehensive about leaving my tent, but remember how good it was to have had it up when I arrived two days ago. It is well sheltered by a high wall of boulders. I add a few more rocks inside the tent, concentrating on the ground sheet by the corners. Then I zip it up tight – and am gone.

Two hours later I am back down at Base Camp, just in time to re-pitch the vintage blue Gemini before dinner is served, courtesy of Inka.

For the 36 hours I am down at Base, I sort of become an honorary member of the Singaporean Aconcagua expedition. They are a wonderful bunch of three men and five women. The leader is a bit of a celebrity in their homeland: Joanne Soo, a summiteer from the successful Singaporean Women’s Everest Expedition in 2009 and of Cho Oyu in 2007. The rest of the team are less experienced – most having climbed no higher than Elbrus, before coming to Big A. They have employed the services of two Inka Guides, Ariel and Paula.