Rainier's Disappointment Cleaver Route: A Conga line up a giant snow cone

By way of disclaimer, I don't want to reduce the accomplishment of anyone who makes it to the summit of Mount Rainier. It is a difficult mountain to summit. In the best of conditions it involves carrying a full backpack 4.1 miles up the Muir snowfield to 10,080 ft Camp Muir or 11,000+ Ingraham Flats, attempting to sleep in the early afternoon in preparation for a 12 am start across the heavily crevassed Ingraham Glacier, and slogging it up steep snowy switchbacks for 6 1/2 hours or more to get to the crater rim.

Having attempted Mount Rainier via the standard route twice before (and failing twice before) the most daunting aspect of climbing of Mount Rainier is variable weather. Maritime layers come down from Alaska and crash into the ultra-prominent mountain in waves of cold wind, rain and snow. Camp Muir lies in a saddle behind Cathedral Rock and Gibraltar Rock because, as a site, early climbers could still find pebbles that had not been blown off by the often fierce winds. Unlike other mountains outside of the western slopes of the Pacific Northwest no other Cascade volcano subjects climbers more to the challenges of going from wet to cold and windy conditions. Suffice it to say, on a typical day you never completely feel either dry or warm, no matter how many layers of clothing you put on. On a bad day, the danger of hypothermia is real.

![Lenticular over Rainier]()

Prior to this summer's unbelievably mild, high-pressure system conditions, this had been my experience of Rainier. A 1994 solo attempt got me only as far as Camp Muir to face complete whiteout conditions and climbers waiting for a window of good weather to summit. A 2007 attempt was worse: 5 hours of driving rain and whiteout conditions up to Camp Muir. Soaked boot liners, gortex that did not hold up, cold winds, sideways blowing snow...and this was in the middle of July!

![Viesturs, Rainier s most famous mountain guide]()

A few climbers summited during our time on Rainier in 07 through a very brief Thursday weather window that closed the Friday morning our team of 6 planned to make another attempt on the summit. We wound up retreating down the mountain through yet another white-out in complete winter storm gear: balaclavas, heavy layers of clothing, goggles, everything wrapped in plastic to keep out the incessant rain of the lower mountain, relying on GPS systems, maps and compasses to show us how to get down without wandering onto the dangerous crevassed Nisqually or Paradise glaciers to either side of the Muir snowfield.

Rainier: A Big Mountain

There is an aura about Mount Rainier that seems unshared by any mountain in North America save perhaps that of Mount McKinley in Alaska. To many it is considered a "Big Mountain" in contrast to the "hikes" in the Rocky Mountains because of its heavy glaciation and challenging weather conditions.

![Whittaker Bunkhouse in Ashford, WA]()

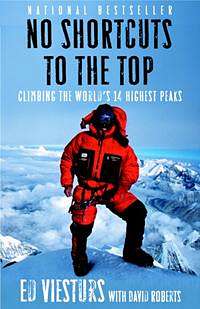

It is the crucible of guide services that send climbers off to noteworthy expeditions in the Himalayas. Famous climbers like Ed Viesters, the Whittakers, Phil Erschler, George Dunn, and too many other famous names from famous climbs are alumnists of the various Guide Services that run climbers from all over the continent up and down Rainier. Guide services such as Exum Mountaineering in the Teton's provide similar services but still seem to lack the cache of Rainier guiding services and their ability to attach prominent names to prominent Himalayan expeditions. Rainier is often considered the training ground for US Climbers planning for climbs in Nepal or Pakistan. And, not suprisingly, if a climber from a non-mountainous region of the country plans a mountaineering vacation, it is probably to Rainier.

![Climbers on the Muir Snowfield]()

Sorting out gear on the porch of our room at the Whittaker Bunkhouse in Ashford, Washington my climbing partner, Kendra, and I first encountered this phenomenon when we met a team of climbers from Delaware who were staying in the adjacent room. The lead climber had summited Rainier 10 times and was leading two other climbers on their first trip up the standard Disappointment Cleaver (D.C.) route. We asked them if they had ever considered climbing in Colorado where we have over 54 mountains higher than 14,000 feet in elevation. No, they had not considered that. Odds are they could probably not name a single Colorado mountain except for perhaps Pike's Peak. Rainier, it seems, is just too iconic to not climb in contrast to other mountains of the continent.

The Hike to Base Camp

As Kendra and I were to discover to our complete surprise-by-way-of-contrast, on a good day Mount Rainier is a human zoo. On my first warm and sunny day ever on Mount Rainier, Kendra and I hiked up to Muir past hundreds of hikers wearing everything from Himalayan-ready mountaineering suits to shirtlessness, shorts, bandanas and skis. Shorts over tights with glacier glasses and floppy hats seemed to be the fashion de rigour for most climbers on the mountain. White foreign legion style hats with neck protection from the sun seemed popular. The wilder the colors, the better. Again, an extreme contrast from the dark forms in heavy layered clothing appearing and disappeared from the fog on the same route during the same time of year two years previously.

![The Crowd at Camp Muir]()

![Tents at Camp Muir]()

Much of the traffic on the Muir snowfield consisted of day hikers just doing a lap to Muir and back for fun. Many hikers were doing training hikes for near-future summit attempts. Some of the hikers were heading up to the guide huts at the Muir saddle. Groups of teens were up on the snowfield, goofing around. Older hikers were getting in fitness walks with abundant views of the surrounding valleys. Kendra and I could spot the unguided climbers due to their significantly larger packs (A visiting climbing from Arkansas summiting with IMG guide services noted to us that he had to carry a 35 lb pack--sleeping bag, extra clothing and personal food. The rest of his needed equipment was taken care of by the guide service. In contrast, Kendra and I conservatively estimated we were carrying 120 lbs of freight between the two of us. 65 lbs for me, 55 lbs for her).

![Kicking it at Muir]()

In the full light of day, the Muir snowfield looks like an ant parade from Paradise Lodge on up. I wound up taking many pictures of just the unexpected crowdedness of the mountain. On the slushy slog up I got my first daylight glimpse of Moon Rocks and Anvil Rock, landmarks that would have been useful during previous descents in near total whiteouts. The push from Moon Rocks to Camp Muir seems like a walk across a snowfield without end, but other that the painful pack weight Kendra and I were lugging, the hike up was uncomplicated and uneventful. Falling into conversation with other climbers along the way was easy.

Camp Muir. Washington's highest beach.

Kendra and I had originally planned to camp at Ingraham Flats, a good stretch past Camp Muir, in order to be higher on the mountain come summit day. But when we checked in with Guide Services on day one to register our climb, display our climbing passes, and reserve a space, we learned Ingraham Flats was at max capacity. Apparently, many climbers coming from lower altitudes acclimatize by camping day 1 at Muir, and day 2 at Ingraham Flats before going for the summit. Some spaces are supposed to reserved for walk-in climbers, but we learned these could fill up days before a climb due to walk-ins that planned to spend more time on the mountain acclimatizing. In short, don't plan to walk-in to Rainier Guide Services and get permission to camp at Ingraham Flats during the height of the climbing season.

![4:30 pm. Bedtime]()

As it turned out, camping at Muir instead of Ingraham Flats turned out to be a blessing in disguise. By the time Kendra and I had reached Muir, our packs were feeling really heavy. To cross over to Ingraham Flats from Camp Muir is a 30-minute walk with a light pack. Or, it can be a horrific slog up steep, sandy and rotten cathedral gap when a 65 lb pack is added. And, per the opinion of a couple of Seattle based climbers we chatted with along the way up to Camp Muir, "Camp Muir is better. Camp Muir has bathrooms." In three trips to Rainier I count myself lucky to still have never used a blue bag, let alone put a full one in my pack for the hike back down the mountain. Thank you climbing rangers. Yea Camp Muir.

![Joining the Line]()

The atmosphere at Camp Muir this day was like that of an après ski lodge. Climbers were tanning on top of their sleeping pads. Young people in tight climbing layers were mingling, eating, napping in the sun, hanging out, boiling water, eating freeze-dried food, and sharing stories. Guided groups hung out together. Independent climbers hung out together. A human diversity unseen in Colorado Mountains showed itself. The stone Muir Hut our team of six had sheltered in 2 years previously was at capacity this year, and a small tent city formed behind the Muir saddle. We walked to the end of a row of tents to set ours up. A couple coming back from the summit freed up a pre-shoveled pad of snow for Kendra and I to camp on, which relieved us of the task of forming a new camping pad out of firm snow with a light weight mountain shovel.

![Roped Up]()

Not much to do at Muir on a good day but tan, eat, and try to sleep before the alarm goes off at midnight. When good weather comes to Rainier, Kendra and I noticed many novice climbers seem to come to the mountain for the first time to try their hand at mountaineering. We were somewhat abhorred to see some teams learning how to self-arrest on the Cowlitz Glacier using an ice axe the day before a summit attempt. Not reassuring were something to go wrong on the mountain the next day. I was reminded of John Krakauer's book In to Thin Air about the 1996 Everest disaster and it hit home how prominent mountains can carry added risks: they attract amateurs that may not know what they are doing but are going for the bigger mountains because it's what they have the time and resources to shoot for, and it attracts crowds that can back up climbers on a route, as they did on the Hillary Step of Everest in 1996, before conditions deteriorate and put all climbers on the mountain in danger.

![Wanded out route]()

![Giant Crevasse on the Ingraham]()

Kendra and I hit the hay around 4:00 pm. Rowdy crowds of climbers stayed up until 9:30 pm chatting as if someone had taken the trouble to hike a keg up to Camp Muir for a pre/post summit party. On and off I remember the tent staying brightly lit until almost wake up time. I remember thinking we were going to start hiking basically as soon as the sun went down. I remember waking up at almost 11 pm and thinking to myself, "No wind!" I draped a black gaiter over my eyes to shut out the light and help me sleep. It was in fits and starts until the alarm went off at 11:45 pm.

Summit Day for Everyone!

You would think it would be hard to pull yourself out of a warm sleeping bag at 11:45 pm to go hiking for 10 hours. But it was really no problem for either Kendra or myself. Everyone in camp already seemed to be up and we could see climbers in headlamps already along the route ahead of us like a line of fireflies in the night. The moon was out and almost full. We dressed in heavier layers knowing we could hit high winds near the summit, and that it would be difficult to make many clothing adjustments once our climbing harnesses were on and we were roped in together. As fortune would have it, it was warm and windless enough on the Cowlitz glacier that we were shedding layers down to light soft shell coats and glove liners within 20 minutes of starting out from camp. Sweat was going to be a bigger problem than cold, even in the dead of night.

![White out Below Pebble Creek]()

RMI, the main climbing service on Rainier, "wands" the route from Camp Muir to the summit using wire wands with florescent tape so climbers avoid running into high crevasse danger areas or getting lost in whiteout conditions. Along the wanded route a prominent "boot track" forms where roped team after roped team follows the same path up to the summit. Along the boot track it is hard to pass. It is hard to stop. And it is hard to take pictures. Kendra and I joined the line of climbers heading on up the Cowlitz glacier to Cathedral Gap. The path across the Cowlitz was obvious. The path up Cathedral Gap was not and we slogged through the rock-peppered sand surface of rotten volcano--a good reminder that snow was our friend on this mountain. We made it to the tents on Ingraham Flats in no time and could see climbers headlamps go way up the Ingraham to a place where the headlamps cut sharp right towards the giant rock known as the Disappointment Cleaver.

Kendra and I were prepared for crevasse danger, especially on the Ingraham. Since our last summit attempt we had learned how to travel safely across crevassed glaciers as a team of two. Our 8 mm rope was knotted in butterfly knots to catch either one of us on the crevasse lip should we fall. We were traveling 30 ft apart to minimize the size of any given fall. We each carried two snow pickets in case either one had to build a snow anchor or ratchet out the other person on a haul line. In retrospect we were over prepared for the D.C. route (yes, there is such a thing). The hardest part of the trip turned out to be getting our back-breakingly heavy packs up to Camp Muir. We had 5 days of instant meals, impermeable rain layers of extra clothing, we could wait out a 5 day storm for a weather window if need be. All useless this year. As conditions turned out, if either one of us had fallen into a crevasse, we would have had an army of climbers either in front of us or behind us to help with a haul pretty much along the entire length of the route.

[img:531566:alignleft:small:]

And crevasse danger was minimal. Three weeks before our trip to Rainier, climbers were still ascending the Ingraham Direct route because the snow cover over crevasse fields has been so heavy this past winter that normally early forming crevasses were still well covered and more direct lines to the summit were available. By the time Kendra and I arrived, the Ingraham Direct had closed, the route from the top of the D.C. had closed. The new route crossed the D.C. way out onto the Emmons glacier; usually a route climbers can avoid until August. The weather for several weeks had been so warm, and the crevasses had opened up so prominently, they were easy to skirt around. One particular crevasse on the Ingraham glacier was large enough to swallow a battleship. An impressive sight from atop the D.C.

From the Top of the D.C. to the Summit

Once one started heading up the Disappointment Cleaver it became so crowded that it was near impossible to stop for more than a few minutes without holding up another rope team. Stopping for a stalled rope team ahead provided opportunities for short rest breaks. Taking photographs was a moot activity until sunrise. And when the sunrise came, the sky glowed red and illuminated the mountain and valleys below. Rest stop atop the D.C. Half way to the summit. Another rowdy scene. Climbers relieved themselves on nearby rocks.

Above the D.C. the climbing is long, tedious, and uneventful. Leg fatigue can be an issue because of the persistence of the climb up snowy switchback after snowy switchback. For Kendra and I, well accustomed to the altitudes of Colorado 14ers, neither one of us found the need to pressure breathe, stop frequently to rest, or even struggled for breath at any point. If you will excuse the Colorado 14er parlance, with adverse weather out of the picture, Rainier is the distance of hiking up the big bowl on Snowmass mountain and back, combined with the monotony of climbing Mount Columbia one false summit at a time, combined with the crowds going up Grey's and Torrey's on a sunny Colorado summer day. Which still makes Rainier a remarkable climb. Remarkable that so many climbers of so many different ability levels come to Rainier every year to attempt to reach the summit and actually make it.

[img:531402:alignright:medium:]

With adverse weather out of the picture, the push to summit was ironically anti-climactic for Kendra and I. We reached the summit crater around 6:45 am just as clouds were coming in and snow started to fall. The temperature began to drop with new weather coming in. We unloaded our packs in the same area some 30 or so climbers were milling around in just inside the summit crater and made the final tired walk across the crater to Columbia Crest: the true summit of Mount Rainier. When we reached the summit we could see Liberty Cap below, the prominent false summit feature at the end of the Liberty Ridge route. Third time was the charm. We traded photos with a few other climbers, and descended quickly to avoid potential problems should the weather deteriorate further.

Heading Down

As we descended, it warmed. The sun broke through the clouds. A lenticular cloud started forming on the summit that might cause issues for climbers going up later. But for Kendra and I, it was an easy and surprisingly fast hike back to camp Muir. [img:531575:alignleft:medium:]

Beautiful penitentes of snow on the D.C. we had not been able to see in the dark proved for interesting photographs. Camp Muir was less sunny and cooler than the day before. Not warm enough for tanning. Many climbers had already packed up and headed out. Others were just mingling, catching quick naps, or packing up before heading back down to Paradise Lodge. After a brief rest we slowly packed up and headed down ourselves. So much for needing 5 days on the mountain to wait for good weather.

Back on the Muir snowfield, climbers were butt glissading down a trench to speed their descent. Kendra joined in, giggling her way down. I refused to put holes in my pants on such a gradual snowfield and plunged my way down through the slush on the lower mountain. After so many climbers successfully summit on a given day, the mood on the lower mountain can change. Weird hats come back out. Goofiness sets in. Kendra herself broke out the pink zinc and returned to Paradise Lodge with a hot pink nose.

[img:531576:alignright:small:]

Rainier, true to form, provided us with a last weather surprise. Above the Pebble Creek crossing half way between Camp Muir and the Paradise Visitor Center, thick clouds had formed. Everything between Pebble Creek and Cathedral Gap was hot and sunny. Everything below was in less than 20 feet of visibility. Kendra and I finished the last two miles in a dense cloud with aching shoulders and knees from the weight of our packs. Kudos to the weather gods this time for the great weather window we hit on the upper mountain. Perhaps some Karmic repayment for all the Colorado mountains Kendra and I had put ourselves through in storms these past two years in preparation for this return to Rainier.

Weather, Weather and more Weather

While never say never, when conditions are favorable the Disappointment Cleaver route on Rainier is fun, but overcrowded. I would readily return to Rainier again and again to try routes like the Emmons-Winthrop, Fuhrer Finger, Kautz Route, maybe even Liberty Ridge, and descend by way of the D.C... I also left Rainier really appreciating the climbing opportunities we have in Colorado, even though less famous, less intimidating by name, less guided by Himalayan base camp coordinators. On our summit day it really did feel like a roped Conga line up a giant snow cone and, although challenging, even Biscuit the climbing dog (RIP) could probably have made it to the top. The conditions were simply too favorable not to summit for most climbers.

That Rainier turned out to be such a different mountain for Kendra and I between 2009 and 2007 causes me to wonder if anyone in the history of climbing has played around with a conditions index to more accurately assess an overall climb’s true difficulty (E.g. the climb was class III, the crux was 5.8 and the conditions were W5: 20 degrees, 45 mile an hour winds, low visibility.) It drives home the point that in mountaineering, sometimes the easiest mountain and the hardest are only separated by a really good storm.

And on this note, per Kendra and my previous attempts to climb Mount Rainier, we traveled unguided but strongly recommend using a guide service if you are unfamiliar with climbing in the cascades and the weather that comes with them, are not a master of using map and compass or GPS systems to get yourself out of trouble if zero visibility conditions hit, or are concerned about route finding through glaciers. Guide services have a strong vested interest in emphasizing the dangers and challenges of Mount Rainier. This is probably much of what contributes to the aura of this mountain above others. But the guides are on the mountain every day and can see where and when changes happen that alter the danger to those who may not know the route or their ability to get in and out of bad weather fast. Even the standard route can be dangerous and unpredictable with the smallest of changes in conditions.

This past winter Kendra and I watched a video Boulder climber Val Hovland put together on her experience with IMG on Everest. One of the climbers commented, “Oh the Sherpas are incredible… So much so that they greatly diminish the challenge and sense of accomplishment.” The RMI guides also do a great job wanding out and guiding climbers up the standard route on Mount Rainier. So much so that on a good day, they can greatly diminish the sense of challenge and accomplishment. Great to be there, good to be home.

Comments

Post a Comment