Accidents happen

As long as people have climbed mountains there have been accidents. And not surprisingly as mountain climbing developed more accidents were recorded. The heroes of the new sport came from the upper-middle class in Victorian England. When in the 1850s the French railways reached Basel and Geneva, the climbing centers Chamonix, Zermatt and Grindelwald were hardly more than a day’s journey from London and could be reached cheaply at a fare of ten pounds. Setting up an expedition with five porters and three guides in 1855 two Londoners had to pay only four pounds each. Not all became heroes, instead some lost their lives in the high mountains. The most famous accident is of course when in 1865 four men fell to their death during the descent of the Matterhorn. Edward Whymper’s ill-fated first ascent of and its aftermath has probably generated more writings than all other fatal accidents have altogether. Thus, we are not going to retell that story, instead a number of less known alpine accidents from the early days of mountaineering will be dealt with.

From the Tongue of the Glacier

When Dr. Hamel, a councillor to Alexander the First, arrived in Chamonix in 1820 thirty-four years had passed since Paccard and Balmat had climbed Mont Blanc for the first time. Since then fourteen parties had reached the summit without any accidents. The Russian Hamel’s reason for attempting to climb Mont Blanc was to test scientific apparatus at high altitude together with M. Selligue, an optician from Geneva.

![Mt Blanc]() Mont Blanc, to the left, overlooking the Bossons Glacier. (Picture by icypeak)

Mont Blanc, to the left, overlooking the Bossons Glacier. (Picture by icypeak)On August 18 a total of sixteen persons including two Oxford undergraduates and twelve local guides made their way up to Grand Mulets. Stormy weather made them stay in their camp for two days. On the third day Selligue and two guides gave up and went down while the rest started for the summit. As they approached the Rochers Rouges, the snow under Hamel’s feet started to give away. The next moment the whole party was carried downwards in an avalanche. Continuing for 400 meters the avalanche ended pouring down into a big crevasse. Three men, the guides Pierre Balmat, Pier Carrier and Auguste Tairraz, fell into the crevasse. Searching was useless and they were considered lost for ever.

Forty years later the Bossons Glacier began to throw out strange things like fragments of clothing, expedition material and above all human remains. A skull with hair, an arm, a hand, a foot and more emerged from the tongue of the glacier. Joseph-Marie Couttet, one of the surviving guides now in his seventies, could identify each object and said in the police report: “I never thought that I once more should grasp my old friend Pierre Balmat’s hand”. The poor men had during forty years travelled ten kilometrers from the crevasse where they vanished to the end of the glacier.

![Mouth of Glacier des Bossons]() The tongue of the Bossons Glacier as of 2008. (Picture by hiltrud.liu)

The tongue of the Bossons Glacier as of 2008. (Picture by hiltrud.liu)In 1866, about at the time the Bossons Glacier was spitting out human relics, the Englishman Henry Arkwright arrived in Chamonix together with his mother and two sisters. Despite the lateness of the season he decided to try to climb the Mont Blanc. On the evening October 12 he was sitting together with his sister outside the Grand Mulets hut. A Bengal light was fired to signal their arrival to the hut. Henry’s younger sister had been allowed to accompany him up the Bossons Glacier as far as to the hut. The party included the experienced Chamonix guide Michel Simond and the two porters Francois and Joseph Tournier. At daybreak two parties left the hut at 3051 m with 1800 vertical meters remaining to the summit of Mont Blanc. The first was Henry and his three men, and the second the hut warden Sylvain Couttet and a friend. After traversing the Grand Plateau they stopped to have breakfast together and to discuss which route to take. Should they use the Ancien Passage taken by Balmat and Paccard on the first ascent in 1786? The alternative was the longer Corridor discovered in 1827. To gain two hours they chose to take the Ancien Passage even if it was more dangerous with steep snow, crevasses and rising cornices.

The men had been walking only a short time when a crack was heard above. Blocks of ice came rushing down. When things began to clear Henry and his men were dead while Couttet and his friend miraculously survived. All the dead were found except for Henry. After days of searching a new avalanche covered the area where the accident took place and Henry was never found. Almost.

In the summer 1897 the Arkwright family received a telegram that simply read; “The remains of Henry Arkwright from 1866 have been found”. After 31 years (sic!) he had emerged from the tongue of the Bossons Glacier. The head and the feet were missing but there was no doubt of his identity since a handkerchief with his name was found in his waistcoat pocket. Henry Arkwright as Who Was He?

Schreckhorn - the Peak of Terror

The young English Rev. Julius Marshall Elliott was the first, after Whympers party in 1865, to climb the Matterhorn by the Hörnli Ridge. Together with the Zermatt guide Franz Biener he had spent four summers in the Alps making his name also climbing Mont Blanc, Dom and Weisshorn. In the Berner Oberland he already had ascended several 4000 meter peaks when on Monday 26 of July in 1869 he and Biener made preparations outside the Hotel Adler in Grindelwald. Together with the porter Joseph Lauber they had the 4078 meter high Schreckhorn in mind. The Schreckhorn, translated The Peak of Terror, climbed for the first time in 1861, had a reputation to live up to its name.

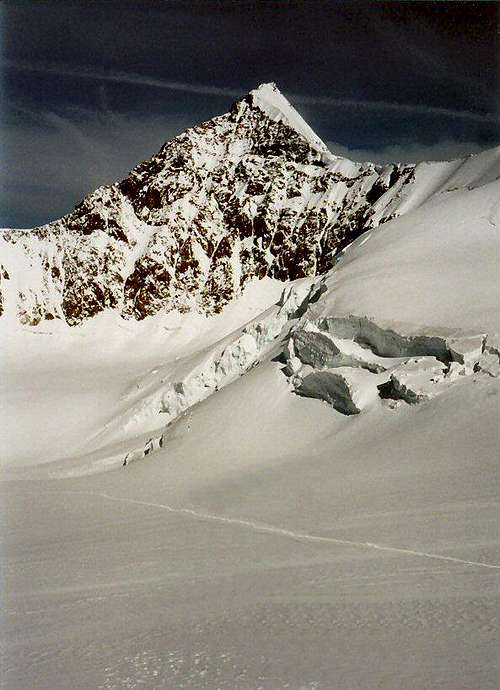

![Schreckhorn north face, a...]() Schreckhorn, the highest peak, with its north-east face down where Elliott fell. (Picture by Mathias Zehring)

Schreckhorn, the highest peak, with its north-east face down where Elliott fell. (Picture by Mathias Zehring)A second party which also included an English Reverend by the name of P. W. Phipps and his guide Peter Baumann had the same goal. The two groups spent the night at Kastenstein and joined forces up to the steep Schreck Couloir to the Schrecksattel at 3914 m being the low point between the Schreckhorn and the Lauteraarhorn.

Adopting an over-confident attitude Elliott refused the offer of Biener’s rope. Elliott was first in line up the ridge, now called Elliotts-Wängli after his name, leading to the summit. At one point he tried to jump from snow covered ground over to a rock but lost his footing. Several version of what happened exist, the most dramatic telling of how Biener caught his arm when he fell. Holding him long seconds before he had to give up only seeing how Elliott disappeared into the abyss of the North-East face. He fell several hundred meters to his death down to the Lauteraar Glacier. His body was recovered two days later, not without difficulty. Elliot was buried outside the Grindelwald church where his headstone can be found today.

![Julius Marshall Elliott…]() The Elliott Headstone in Grindelwald cemetery.

The Elliott Headstone in Grindelwald cemetery.Lyskamm - the Man Eater

The following text appeared in a London newspaper in September 1877:

“A telegram from Geneva states that the Englishmen Mr Lewis and Mr Paterson with three local guides, the brothers Knubel, left Zermatt on Sept. 7 to ascend the Lyskamm; all five were killed by the bursting of a glacier. Mr Lewis and Mr Paterson were buried in the English cemetery at Zermatt. Subsequent information states that the party left the Riffel Hotel a.m. on Sept. 6 with three guides. As they did not return that evening, a party started next day to see whether they had gone down the Italian side, but they returned with the news that all had perished, owing, so far as they could make out, to the giving way of a cornice of snow on the edge of the mountain. The whole five bodies were precipitated a distance of 3000 or 4000 feet, and death must have been instantaneous. The accident is the most terrible that has ever occurred here, and a universal gloom is spread over the place.”

![East summit from the south side]() The Lyskamm East summit seen from south. The five men fell from a point to the right of the summit down to the glacier.

The Lyskamm East summit seen from south. The five men fell from a point to the right of the summit down to the glacier.Charles Gos writes in his “Alpine Tragedy” what likely happened:

"The snow was good. They found it easy to place their feet, which bite into the crust of sparkling crystal. But are they not drifting too far from the crest? To assess the thickness of the cornice and to estimate the extent of its overhang they should be below it, or lower down, at a point clear of snow. But they are above it. Now it is just at this point that very thin fissures begin to run parallel to the cornice at the edge of the crest, blue serpentine lines on white snow. They are too far to the left, completely above the overhang. The five men never reach the edge. For them it is all over. For suddenly, some ten feet from the arête, the snow beneath them moves and slips away, like a ship sinking in the trough of a wave. They are swallowed up in a flash and vanish into the abyss of the Italian side in a cloud of snow and ice."

![Lyskamm traverse E-W]() The Lyskamm ridge. Climbers close to where the cornice broke. (Picture by as)

The Lyskamm ridge. Climbers close to where the cornice broke. (Picture by as)In 1896 an almost identical accident took place when the German Dr. Max Günther with his guides Roman Imboden and Peter Ruppen died when a cornice broke. These tragic events have given the Lyskamm a bad reputation and the nickname the Man Eater (German: Menschenfresser). Accidents still happen on this mountain and are even witnessed by SP-members as described in this trip report by as: Lyskamm traverse

No Rope and Storm on Matterhorn

On September 7, 1879 The New York Times reported:

“Mr Moseley, unroped, was standing on a narrow ledge of rock, when, owing, in all probability, to a thin coating of ice which covered it, he slipped, and Mr Craven had the horror of seeing his companion whirling through the air for some thousands of feet, and then disappear, he believes at the base of the Matterhorn, and which also skirt its glacier.”

Dr. William Moseley from Boston, USA, only twenty-nine years old arrived in Zermatt in early August 1879. He was together with his friend W. E. Cravern and two Oberland guides; Peter Rubi and Christian Inäbnit. They had together climbed more than twenty peaks and intended to add the Matterhorn to the list. Fourteen years had passed since the 1865 tragedy and no more victims had been claimed.

![Solvay Hut and Lower Moseley Slab.]() The Solvay Hut and Lower Moseley slab on the Matterhorn. (Picture by teochristopoulos)

The Solvay Hut and Lower Moseley slab on the Matterhorn. (Picture by teochristopoulos)The party climbed strongly and Moseley felt so confident that he insisted on climbing parts of the route unroped but the guides persuaded him not to. At nine in the morning they reached the summit where they stayed for twenty minutes. Again on the descent Moseley wanted to climb without the rope and despite protests from the others he took the rope off. At the steep part above where the Solvay hut later was erected the accident happened. Moseley slipped and fell to his death.

Charles Gos writes in his Alpine Tragedy:

”Then he leaps. Unhappily his taking-off point gives way beneath him. He falls. Now Moseley can see tragedy loom before him in all its horror. Though out of vanity he had wanted to abandon the rope, he has no wish to die. Now he slides on his stomach, his hands trying to grapple with the rocks that fly very swiftly by. He succeeds only in tearing off the ends of his fingers. Nearly two thousand feet below, on the Fruggen Glacier, the last parabola ends.”

Moseley’s name is forever associated with the Matterhorn since the steep parts both below and above the Solvay Hut are named after him as the Lower and the Upper Moseley slabs. The Moseley name is also remembered by a donation made by his parents to the surgical chair at Harvard Medical School.

![On the Dach of Matterhorn 4478m]() Climbing on the ”Dach” of the Matterhorn, where the Borckhardt party was caught in a storm. (Picture by Cyrill)

Climbing on the ”Dach” of the Matterhorn, where the Borckhardt party was caught in a storm. (Picture by Cyrill)In 1886 climbing the Matterhorn had become quite a fashionable thing. On Saturday 14 August this year two Englishmen, John Davis and Frederic Charles Borckhardt, arrived at Zermatt. After seeing the beautiful pyramid they decided to climb it and started to make enquiries. Davis had some experience from the English hills and as late as the week before he had climbed the Titlis in Engadine. Borckhardt knew little of mountain climbing but was considered a hard walker.

At three o’clock on Thursday morning the sky was clear. Despite a hard wind three parties set out from the Hörnli hut. Davis and Borckhardt were led by Fridolin Kroning and Peter Aufdenblatten, two young Zermatt guides. At nine o’clock they arrive at the summit, not at all tired. The sky was grey and the view was a disappointment to them. Descending only a short section the weather suddenly changed. The air became bitterly cold and hail poured with violence. Everything became white. With difficulty they reached the place called The Roof (Dach in German) were they met another party. From there the conditions grew worse.

The party spent the night in a blinding snowstorm and the next morning Borckhardt was too weak to move. Thirty-eight hours after leaving the hut Davis and the two guides crossed its doorstep again. Poor Borckhardt lay dead high on the mountain at about where Moseley fell seven years earlier. The guides were criticized for not staying to help their client.

The following could be read on the first page of Evening Post, 6 November 1886:

One of the shortest wills was found in his pocket. He wrote in pencil on a small piece of card: “I am dying on Matterhorn. I leave all I possess to you, my dear sister. God bless you.”

Tragedy on Dent Blanche

Some say that Dent Blanche is the most magnificent of the Valais 4000 meter peaks. T. Kennedy and party made the first ascent along the south ridge, today’s normal route, in 1862. The route on the more difficult west ridge was first climbed in 1882 by a foursome including the Grindelwald guide Ulrich Almer. The ridge is named Viereselsgrat after Almer’s comment after reaching the summit after 12 hours; “Wir sind vier Esel” (We are four asses). At their return to the Stockje Hut, at the far end of the Zmutt glacier, the exhausted foursome was taken care of by W. E. Gabbett and his guides Joseph-Marie Lochmatter and his son Alexander.

![Dent Blanche 4357m - south ridge]() Looking down the south ridge on Dent Blanche (Picture by Cyrill)

Looking down the south ridge on Dent Blanche (Picture by Cyrill)The Englishman W. E. Gabbett, from the Universty of Durham, had climbed in the Dauphiné Alps and had now come to Valais. Next morning the foursome descended to Zermatt while the Gabbett party set out to climb the Dent Blanche. They were seen toiling up toward Col d’Hérens on their way to the start of the south ridge. They were never to be seen alive again.

When Gabbett and his guides did not appear as expected in Zermatt a rescue party was formed. In total eleven guides and three Englishmen set out to search. It was first thought that the accident had happened on the eastern side of the mountain but there nothing was to be found there. Eventually the three bodies were located on western (Ferpècle) side below the bergschrund. Fifteen meters apart they formed an equilateral triangle having fallen 800 m from a point near the summit. No one will ever know what really happened. Mr Gabbet’s grave can be found in the Zermatt cemetery while the two guides were buried in their home village St. Niklaus.

![Dent Blanche 4357m]() Dent Blanche from the west. The south ridge is on the right where the Gabbet party fell from near the summit down to the glacier. The steep Ferpècle ridge, from where the Jones party fell, goes direct to the summit slightly to the left. (Picture by Cyrill)

Dent Blanche from the west. The south ridge is on the right where the Gabbet party fell from near the summit down to the glacier. The steep Ferpècle ridge, from where the Jones party fell, goes direct to the summit slightly to the left. (Picture by Cyrill)Some years later in 1899 a party set out to climb Dent Blanche by the unclimbed rocky western ridge also called the Ferpècle ridge. The group included the able English climber Owen Glynne Jones, his partner F. W. Hill and three Swiss guides. More than half the way up the ridge the way was blocked by a vertical section covered with verglas. The guide Elias Furrer tried to bypass the difficulties turning to the right. Clemenz Zurbrigen and Joens tried to help by putting up an ice axe under Furrer’s foot. At the crucial move trying to reach a ledge Furrer slipped taking four of his friends with him in the fall. Hill was saved by the rope breaking between him and Jean Vuignier. Left with only a ten meter rope he succeeded in climbing to the summit, to bivouac during a stormy night and to descend along the south ridge. Forty-eight hours after the accident he was able to tell the tragic news in Zermatt.

From a personal point of view I planed to climb Dent Blanche ten years ago. I had studied the south ridge in great detail and knew of all the difficult passages. Staying in the village Zinal several days, waiting for the weather to improve, we finally had to give up. Was it a decision made higher up not to let me climb this beautiful and dangerous mountain?

Lightning and Avalanche on Wetterhorn

The Englishman William Penhall was an accomplished mountaineer who made several first ascents in the Alps: The Zinalrothorn by the west face together with Martin Conway, and the the Dürrenhorn with A.F. Mummery just to mention two. In addition, The Penhall Couloir on the west face of the Matterhorn is named after him.

The 1st of August 1882 the 24 year old medical student Penhall and his friend F. J: Church met in Grindelwald. Their plan was to travel across the Bernese Alps to Zermatt together with the famous guides Andreas Maurer and Rudlof Kaufmann. Eager to get started Penhall suggested that he and Maurer should climb the 3707 meter high Wetterhorn directly from Grindelwald without an overnight sleep. It was snowing high on the mountain the coming days. One hour after midnight the 3rd of August they left the Bear Hotel and disappeared into the black night. Getting higher and higher up the Upper Grindelwald glacier we can assume that they talked about the experiences they had had in the mountains; Maurer of his ascent of Aiguille Verte and Penhall of his race with Mummery to be the first to climb the Zmutt ridge of the Matterhorn.

![Wetterhorn 3692m]() Wetterhorn in the center. Willsgrat is the ridge leading up to the col. (Picture by Cyrill)

Wetterhorn in the center. Willsgrat is the ridge leading up to the col. (Picture by Cyrill)The climbers were expected back in Grindelwald the same afternoon. When they had not returned by nightfall anxiety was spreading among their friends. Next morning a group set out to search for missing men. Crevasses were explored as they travelled the glacier but nothing was found. Coming to the small Gleckstein Hut belongings of the missing were found. Through binoculars tracks in the snow leading up from the hut could be seen. They mysteriously disappeared higher up. The terrible truth was that Penhall and Maurer had been hit by an avalanche in the Krinn couloir close to the ridge called the Willsgrat. In the evening the bodies arrived down in the valley wrapped in sacking and lashed to poles.

![William Penhall...]() Penhall and Maurer share a double headstone at the church wall in Grindelwald.

Penhall and Maurer share a double headstone at the church wall in Grindelwald.On the morning of August 20, 1902 a funeral procession with two coffins went from the church in Grindelwald to the railway station. The Scotsman James Brown and the guide Solomon Knubel were out on their last journey. Both men had plunged to death on the Wetterhorn four days earlier.

Scarcely had they been loaded on the train when a terrible storm broke out. The lightning struck in several places, also on the summit of the Wetterhorn. This had been of no significance if there had been no people on the summit. The two Irish brothers Robert and Henry Fearon and the two mountain guides Samuel Brawand and Fritz Bohren was resting on the summit when the four were struck and killed by lightning.

When the four men did not return to the village that night, there was some concern but nobody wanted to believe the worst. Two days later the awful truth was revealed. Robert Fearon and Samuel Brawand was found dead roped together and blackened by lightning at the very summit. Part of the steel in Brawand’s ice axe had melted and the shaft was split in half. The other two could not be found despite intensive searching. A month later on September 22, the two corpses were discovered in a hidden glacial crevasse further down the mountain. The beautiful mountain had once again shown its worst side.

![Robert and Henry Fearon…]() In Memory of Robert Burton Fearon, age 36 and Henry Charles Digby Fearon, age 29.

In Memory of Robert Burton Fearon, age 36 and Henry Charles Digby Fearon, age 29.In the aftermath it was suggested that they should not have attempted the climb when the weather turned threatening. However, the local storm must have developed very suddenly without warning. The four men were buried together in grave at the Grindelwald cemetery where the headstone tells the story. The remains of Samuel Brawand’s ice axe can be seen at the local Museum.

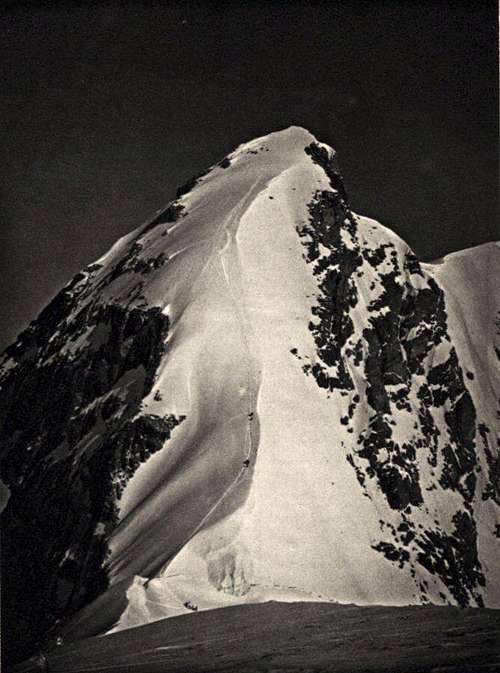

Jungfrau – the Evil

On Wednesday, July 13 1887 six young men arrived at Lauterbrunnen. In the evening they sat around a big table in the Staubbach Hotel. They were eating a steaming hot soup and discussing their plan to climb the Jungfrau from the Rottal. Another party appeared and they changed the subject since the wanted to keep their plan a secret. The first day they reached the Rottal hut. The peaks around were hidden in dark clouds.

At five o’clock next morning they were again on the move. As they closed the door someone thought it would be a good idea to leave a note of the party’s plan. Together with their names they wrote “On the way to the Jungfrau.” In a good mood they even captured a little marmot and one of the young men decided that the animal also should make the ascent. The marmot was rolled in a handkerchief and carefully put in the knapsack.

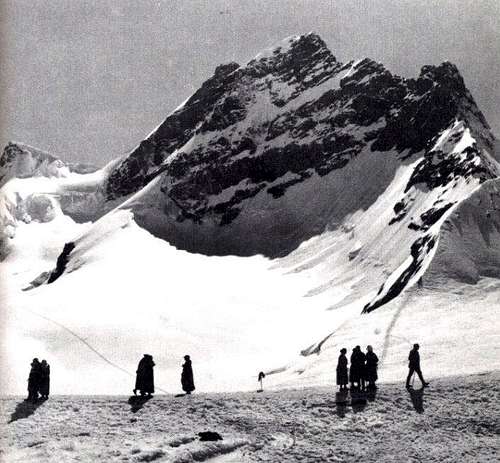

![Jungfraujoch]() The Jungfrau with its South-West ridge to the left where the men fell down to the glaicier.

The Jungfrau with its South-West ridge to the left where the men fell down to the glaicier.Curiosity about the expedition arose in the valley. Through telescopes in the morning six climbers had been seen low on the south-east face. At midday dense clouds piled up heralding a storm. The enthusiasm of the climbers was still high. By two o’clock they had overcome most of the difficulties. Thunder roared in the valley, the wind howled as the six men made their way up the summit arête. One man stopped saying that he has had enough. Leaving him sheltered by some blocks the others continued. The summit was in fact no more than twenty meters away. But in the storm a meter transformed itself into a kilometer.

The stayed on the summit for only a minute, long enough to congratulate themselves on their victory. The tracks on the arête were already covered and like blind men they found their way back to the waiting comrade. “These storms never last very long”, someone said and they decided to stay where they were for the night. Clearing away the snow and piling up stones they created a small platform giving some shelter. They were just a few meters from the edge of the enormous precipice that ends on the Jungfraufirn. Six men and a marmot watched the wind blow and snow fall all night. Their bodies frozen stiff they arose at six o’clock. “The marmot is dead”, someone said without getting an answer. “We shall be at the Rottalsattel in thirty minutes”, was heard from another voice. Eight o’clock they started down in two ropes, three men in each.

![The Jungfrau south-east ridge]() The six men of 1887 fell to their death down to the Jungfraufirn on the right side of the ridge.

The six men of 1887 fell to their death down to the Jungfraufirn on the right side of the ridge.Camouflaged by snow the caravan advanced with cautious steps. The man in the lead stopped, before him, beside him, to the left and right there was nothing to see, nothing but total whiteness. One more step and it was too late. The snow collapsed and three men were dragged into the gulf. The other three ignorant of the tragedy beneath them walked the same way into the abyss.

The Unfortunate Hopkinson Family

![Petite Dent de Veisivi]() Petite Dent de Veisivi. The Hopkinson family fell from a point close to the highest point to the base behind the ridge in the foreground. (Picture by il.rocciatore)

Petite Dent de Veisivi. The Hopkinson family fell from a point close to the highest point to the base behind the ridge in the foreground. (Picture by il.rocciatore)There is a rather short Wikipedia page on John Hopkinson. He is said to have been a British physicist, electrical engineer who invented the three-wire (three-phase) system for the distribution of electrical power. At the end of the page there is a sentence that draws our attention: “Hopkinson and three of his children, John Gustave, Alice and Lina Evelyn, were killed in 1898 in a mountaineering accident on the Petite Dent de Veisivi, Val d'Herens, in the Pennine Alps, Switzerland.” What happened?

The Hopkinson family had spent several summers together in the Alps climbing a number of peaks. The mountains were like a family affair to them with the father being a distinguished member of the Alpine Club. In this summer 1898 the family already had ascended impressive mountains like Rouges d’Arolla (3646 m) and Mont Collon (3637 m).

Before returning to England they decided to climb Petite Dent de Veisivi (3183 m). This is neither a distant nor a particular high peak but still offers serious rock climbing. Hopkinson and three of his children, all around twenty, left the village Arolla half past seven in the morning Saturday the 27 August. This rather late start was possible since the approach did not include any glacier crossing with softening snow bridges. On their way to the foot of the mountain they caught glimpses of both the mighty Dent Blanch and the snow cowered Dent d’Herrens.

![Hotel du Mont-Collon at Arolla]() Hotel du Mont-Collon at Arolla, where at a dinner table for six, four places were unoccupied. (Picture found on www.philosophie.ch/eidos/events2009)

Hotel du Mont-Collon at Arolla, where at a dinner table for six, four places were unoccupied. (Picture found on www.philosophie.ch/eidos/events2009)The father uncoiled the rope. They were not used to climb in two parties so all four tied in the same rope, Jack leading, Lina as second followed by the father. At the end came Alice, the older daughter. They started up the steep rock making use of their steel-shod boots.

Mrs Hopkinson and their youngest son had spent the day playing tennis. In the evening dinner was served in the large dining-room of the Hotel du Mont-Collon at Arolla. At a table for six four places were unoccupied which attracted attention. “There is no need to worry”, someone said adding “Climbers, madam, are just like artists; they can never return in time for their meals”. But as the hours went by the seats stayed unoccupied.

Finally at midnight it was decided to organize a search party. Early on Sunday morning in the grey light of dawn the bodies were found. At the base of the wall under the summit the Hopkinson family lay all roped together. They had fallen about 200 meter from a point close to the summit.

The grave of unfortunate members of the Hopkinson family is found in cemetery at the village Territet, close to Montreux at the shore of Lake Geneva. The inscription on the head stone ends: “In their lives and in their death they were not divided”

Lesson to Learn

There are obviously things that a mountaineer should try to avoid: Things like being in the line of an avalanche, like falling into a crevasse, like being hit by lightning, like getting caught in a severe storm, like walking on a cornice, like climbing unroped or even like climbing too many in the same rope. Avoiding all this and not being over-confident the day out in the mountains will be fine.

Sources

- Braham, Trevor: When The Alps Cast Their Spell, The In Pinn, Glasgow, 2004.

- Clark, Ronald: The Early Alpine Guides, Phoenix House, London, 1949.

- Dumler, Helmut and Burkhardt, Willi: The High Mountains of the Alps, Diadem Books, London, 1994.

- Gos, Charles: Alpine Tragedy, Allen & Unwin, London, 1948.

- Rey, Guido: The Matterhorn, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1907.

- Rudi, Rudolf: Im Tal von Grindelwald, Band II, Verlag Sutter Druck, Grindelwald, 1986.

- Unsworth, Walt: Savage Snows, The Story of Mont Blanc, Hodder&Stoughton, London, 1986.

Thanks to desainme and isostatic for comments on the original text

Comments

Post a Comment