"A Hell of a Way to Start"

It was 1:00 a.m. when I awoke to the sound of the wind tearing at the tent we had lazily staked down with rocks the night before. We were sleeping in the campground below Timberline Ski Lodge, and it had scarcely been 5 hours since I had lain down for the night. I had set my cell phone alarm clock, but there had been no need. I woke on my own at the predetermined time; for I knew the moment had arrived for what we were ready to do, and I needed no external clock.

Having set out our clothes the night prior, and having set aside our packs, gear, and rope for the ascent, I broke down the tent and hastily shoved it into the back of the car. There was not any more delaying now. The time had come, and I was too excited to wait any longer for this day to begin.

No moon was hovering over us in the sky as we stepped out of the car and onto the dust-covered, almost vacant, parking lot. I was immediately taken aback by the velocity of the wind as I watched some stray papers on the floorboard of the rental car being ripped out and sucked into the dark void of the night. I thought it had to have been blowing in at around 50 m.p.h, but I couldn’t be sure.

“I don’t like this wind,” Chris voiced apprehensively.

“Me neither,” I said reluctantly.

I knew the wind could become an issue if it sustained itself at this level during the climb, especially after we ascended above 9,000 ft. I had heard stories of people being blown off snow slopes, and of winds lifting people into the air on the summit of Longs Peak and moving them 10 ft. before slamming them back down into the snow. But I didn’t want to turn back before we had even started.

“This really isn’t that bad,” I lied as I proceeded to open the trunk and shake out my pack. “I’ve seen worse.”

Chris looked at me, both anxious and doubtful, but I managed to keep a straight face and concentrate on what I was doing, to avoid showing any signs of hesitation myself. I felt bad about my little lie, as white as the snow around us, but knew that it had been perfectly calm the night before when we went to bed. So I ran these things through my head over and over again, rationalizing to myself, and holding on to the hope that conditions might improve. After all, the wind had caused a release of adrenaline within, and in a half-loony kind of way, the conditions were beginning to excite me; I thought it might add a little additional aspect of challenge to the climb.

After a while we finally agreed to start moving, so I laced my cumbersome Koflach snow boots and stowed my crampons on an outside pocket of my pack. I laced a strap around the shaft on my ice axe and fastened it tight to the daisy chain on the back. I hoisted my pack onto my shoulders and steadied myself while I slowly and deliberately clipped my hip strap and yanked it tight. I donned my head torch and set off across the asphalt.

![Me]() Me heading off into the night

Me heading off into the night

We found the trail leading to the start of the snowfield and to the ski lifts that we could see in the distance. High on the slopes a truck’s engine groaned and dim lights shone down past the ski lifts upon the old snow that now lay above us. Evidently, it was plowing and grooming the runs for a ski resort that stays open 11 months out of the year. Although it was July, there was still snow at 7,000 ft. and maintenance men were busying themselves with preparations for the morning snowboarders. But those who would come to ski wouldn’t arrive for another 6 hours, and it was an eerie and mystic feeling to be trudging up towards the snow slopes alone at 1:00 in the morning.

Although there was no moon, the stars shone brilliantly, and I decided to power down my head torch to its lowest setting in order to conserve battery power. I then began to drift into a half-hypnotized walking rhythm as I marched into the darkness, steadying gaining altitude as I climbed up and away from the ski lodge that we had left at the parking lot not too long ago.

“Are you doing OK?” Chris shouted from a distance some 50 yards ahead of me as he turned around to get a visual on my progress. I started to feel out of shape, considering that I was 30 years younger than he, and yet he was in tremendous shape and was already leaving me in the dust. The truth is I probably was, since having just returned from an 18 day sailing trip to the British Virgin Islands with my girlfriend and her family, which consisted entirely of drinking heavily, sleeping, eating, and lying on beaches during sailing breaks between the islands.

“I’m fine!” I answered; frustrated at the wasted conditioning I had done before the sailing.

I was soon too far behind to care, but I continued moving and told myself that ‘slow and steady makes the summit.’

We trudged onward and upward and eventually we reached what looked to be an abandoned ski lift building. As we stopped to rest and take a drink the wind was still whipping and as I stepped around the corner of the building I was met with an onslaught of cold rain blasting down from the slopes higher above. I looked up and saw the lights of the snowmobile flittering about and decided they must be making snow, since it had not been raining on the way up.

After a brief but much needed rest we slammed our packs back onto our packs and continued walking until we reached the intended waypoint an hour or so further up the slopes. It was a warming hut used by skiers during the cold winter months. Based on the beta we had read, we now knew that we were at around 7,000 ft. Chris’s altimeter confirmed this. We would near the end of the ski lifts within another 500 vertical feet.

But before we made any effort to regain the slopes and gain any more elevation, we took 15 minutes to hydrate and eat some candy bars. The break was well-needed, but after this amount of time I began to grow anxious once again. Accordingly, I fetched my crampons and clipped my boots into them. I then strapped on my gaiters, which would provide my clothes and legs protection from the acutely protruding spikes, which had just been sharpened before the climb. Chris followed through with the same motions, and soon we were off, ice axes in hand and facing up and inward towards the mildly inclined 35 degree mixed snow and ice slope.

It didn’t take very long for the slope to increase, as soon we were trudging up a 45 degree incline, and I was glad I had put on my crampons. My mind began to wander as it so often does on long pushes, and I began to think about philosophical issues that shouldn’t be considered if the climb got any more difficult. I was interrupted by the first rays of the light snaking over the mountainside, cast out by a sun that was struggling to break its way through the early dawn clouds.

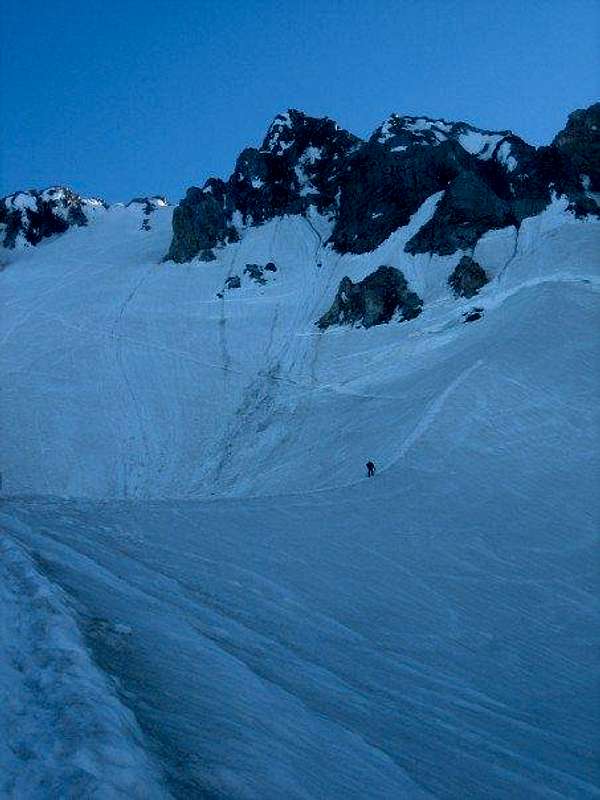

![Pre-dawn approach, Mt. Hood]() Alpine start

Alpine start

It was both upsetting and welcoming. For one, it would soon be getting much warmer, which would make the climb less enjoyable. And soon the silent beauty of the night would be gone, and we would have to keep pushing for the summit as to avoid rock fall on the way down.

![Mt. Hood shadow]() Mt. Hood Shadow

Mt. Hood Shadow

I was also disappointed to see the grand shadow of the mountain shrinking behind me, getting ever smaller as the sun rose higher into the sky. The enormity of it was stunning, and I hated to see it go. On the other hand, I knew with the coming of the early morning light, photo opportunities would abound. And so they did.

Around 9,000 ft. I began to tire more quickly with every step I took. I knew it wasn’t the altitude, because I had been to 18,000 ft. before. I started to curse the two week sailing trip which had put me so temporarily but miserably out of shape. I stopped to pause often, and if Chris noted that I was slowing down he said nothing, although I knew he had to of spied a hint of exhaustion in my face. I wanted the summit badly, and to avoid showing signs of tiredness, I would adjust my pack or shed layers of clothing when I stopped as to make it seem like I was occupying myself and not just idling. But I also stopped frequently to enjoy the views, and then would find myself hurrying to catch up because I had been stopped for too long, only to find that that kind of pacing wasn’t helping my fatigue. So I said to myself, “slow and steady makes the summit.”

The angle of the slope had not yet mitigated, and showed no signs of doing so. I could see Illumination Rock behind me now, vanishing with every step I took. I was passing Crater Rock and didn’t look back, keeping my eyes on the snow ridge looming in the distance. Scree covered the ground between me and the ridge, and the path to it was broken with moderately sized boulders. I could hear the irking screech of my metal crampons scraping across the rock like fingernails across a chalkboard.

![Crater Rock]() Me passing by Crater Rock

Me passing by Crater Rock

Twenty minutes passed, and with it I had finally passed the small boulder field that had been exposed by melting snow amidst the mid-July warmth. Suddenly the summit came into view, or at least what I thought was the summit. In actuality it was a ridge leading to the summit proper, which was elusive to my eyes from where I stood.

![Hogsback Ridge]() Hogsback Ridge & upper Mt. Hood

Hogsback Ridge & upper Mt. Hood

I marveled at the height and began to wind my way along the snowy boot track towards Hogsback Ridge, with Chris now much closer in front of me. From where I stood, the Hogsback ridge looked nothing like what I imagined. The winter storms were 6 months removed from covering it with that magical powder I had seen in the photographs and glazed over before the trip.

It is frightening the dangers a mountain hides from you with its own topography. The way a mountain unfolds before you as you climb it has a special way of obscuring hidden dangers, altering distances, and quite simply confusing the hell out of you about where you are. And so quite accordingly, as I reached Hogsback Ridge I saw how harrowingly close the fumaroles actually were to Hogsback Ridge. My God, I thought. One slip would send me sliding into one within seconds if I failed to self arrest.

![Fumarole]() Fumarole

Fumarole

Fumaroles are essentially holes in volcanic mountains where the glacier has either pulled away from a rock wall or where volcanic gases have melted away at the snow. In a sense they resemble crevasses, but they are more than that. They seep sulfur fumes, a noxious and toxic gas that is deadly to any climber who falls into one.

For some incompetent, hapless, or just plain unlucky people that have fallen in, they first begin to burn to death before actually being killed by the asphyxiation rendered by the oxygen voids created in the interiors of the fumaroles. This is how some died in 2001, a year in which a helicopter crashed trying to rescue several climbers who had fallen in or been swept in by other falling climbers who happened by their paths.

I watched Chris unnervingly make his way towards the other end of the ridge. At first it dawned on me that maybe we should have roped up. But then I remembered that one slip by either of one of us would necessitate the other person stopping both of our falls; therefore the danger of roping up outweighed the danger posed by crossing the ridge alone. As Chris passed by the 2nd fumarole, I breathed a sigh of relief, but I knew the danger of falling into one was not over. Now that he was off the ridge, if he slipped, he would simply slide a longer distance before falling in.

![Hogsback Ridge]() Spine of Hogsback Ridge

Spine of Hogsback Ridge

I was now on the ridge myself, looking straight across to where Chris stood at the other end. I dared not think too much about what was below me and some 50 yards down to my left. Instead, I began to make my way towards Chris one scuffle at a time, concentrating intensely on every step and incessantly readying myself for self arrest.

At the end of the ridge, I could see where the team ahead of us had veered to the left and chosen to abandon the continuation of the Hogsback route because of the large crevasse that stood between them and the gulley that leads to the summit through the revered Pearly Gates. The snow bridge across it had collapsed weeks before, so we too would have to opt for a variation of our route that would add an hour to our summit bid.

Without even going forward to inspect a way around the crevasse, we chose to follow the path the team ahead of us had taken—a diagonal traverse of the side of the mountain, which would eventually lead to a series of switchbacks that would take us to the aforementioned ridge that leads to the summit. Soon after altering our path, we came across 3 small, parallel crevasses that could not have been seen from where we were standing before. This is where we have to turn back, I thought. There is no way I’m going to muster the nerve to cross that sketchy snow bridge. After studying them carefully, however, we decided the precarious snow bridge across the three of them would probably hold us up since it had done so for the 3 climbers who had crossed it 45 minutes prior. We probably should have set up some sort of belay for crossing the three crevasses on this bridge, but we didn’t.

So off I went first. One step, two steps, three steps and I had passed the first one. I was now standing over a slice of snow that separated the first two crevasses. It was only 3 inches wide, yet it supported a snow bridge 10 ft. long and 2 ft. wide. As I peered down into the icy depths, I realized that the first two weren’t as bad as we had thought. Due to the angle and narrowness, I could climb out of the first one easily even without ascenders, I thought.

One more step and I froze in my tracks. I was directly over the third crevasse on the snow bridge, and as I looked up from my feet toward the end of the bridge, I had caught a glimpse of the icy cavern gashing this side of the mountain slope in half. I could not see the bottom. I could hear no sound emanating from the icy walls that led into the narrowing depths, and I looked down into them until the darkness of the crevasse swallowed completely the light of the radiant midday sun and I could see no more.

All of the sudden I remembered where I was. How foolish I had been to stop on a snow bridge I hadn’t completely trusted crossing in the first place. But being from the east coast, this was the first crevasse I had ever seen, and I couldn’t help but to marvel at its foreboding beauty.

……With the crevasses now behind us, the diagonal traverse of the snow slope began…..

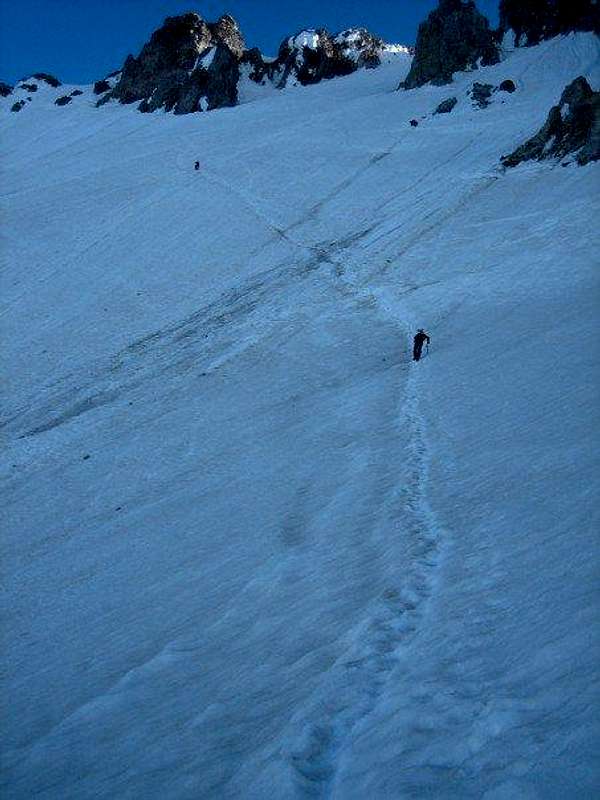

![Upper Mt. Hood, Hogsback Ridge Varation]() Traversing left from Hogsback Ridge: Chris & other climber in the foreground

Traversing left from Hogsback Ridge: Chris & other climber in the foreground

The few pictures I took during its passage attest to the committing nature of the traverse. Once I had started, I was afraid to stop and take out my camera. And I hadn’t forgotten about the two fumaroles looming behind me.

As tired as I was, I kept pressing forward because I knew we had to reach the summit soon or abandon the attempt altogether. Once I had stopped to catch my breath, and saw Chris ahead of me waiting…

“I don’t think you’re going to make it today, Eric” he said. “You’ve simply hit a wall.”

“Yes I am,” I replied defiantly. I wasn’t tired anymore, just mentally strained.

Steadily I made good progress across the traverse and I reached the switchbacks within the hour. I could see 4 or 5 of them winding back and forth towards the ridge leading to the summit. One last push, I thought to myself. But by this time, the angle of the slope had increased to perhaps 50 degrees, and I was slightly nervous about the last section of the climb ahead of me. However, the switchbacks were sent without incident, and as I neared the top of them I could see Chris standing on the ridge snapping pictures.

![Looking down on Hogsback Ridge]() Looking back down to Hogsback Ridge

Looking back down to Hogsback RidgeAhead of me lay 40 more final yards that consisted of a steep scramble to the ridge. Inclined between 50 and 55 degrees to the vertical, our path abandoned the switchbacks altogether and led in one direct, uncompromising push to the ridge. About halfway up the ice slope, I jammed the shaft of my ice axe deep into the snow and ice beside me and steadied myself. I fidgeted with my zipper pocket, being careful not to shake myself or lose my balance, and slowly brought out my camera. Looking down through my legs I snapped a shot of the slope and the fumaroles, which still loomed large despite the sizeable distance that separated me from them.

![Reaching ridge to summit]() Me reaching the summit ridge

Me reaching the summit ridge

Satisfied I had procured a good shot; I put my camera away and looked up at Chris.

“I’m exhausted,” I spat out through clenched teeth and a wild grin. I knew I was close.

“I know, I feel like I should throw you a rope,” Chris mocked me. “Get up here,” he said, “the views are incredible.”

“I can’t wait to reach the summit then,” I added.

I climbed, picked, and crawled my way to the ridge, and when I got there I threw down my pack between two boulders. I stepped up and peered over the other side of the ridge to the glaciers some 2,000 ft. below.

“Come on,” Chris said, my pack has food in it and it’s on the summit.

“Where is it?”

“Just 20 yards across this ridge,” he said.

I looked to my right and saw the boulder-strewn ridgeline meandering toward the summit. It rose ever so slightly up and away, but then sloped down and to the left, ending its path with the top of Mt. Hood.

![Ridge to Heaven]() Ridge to summit

Ridge to summit

As I gained the ridge I became uneasy.

I looked to my left...

![Mount Hood summit view]() A 1,500 ft. drop-off.

A 1,500 ft. drop-off.

I looked to my right...

![Mt. Hood summit view]() A 2,000 ft. drop-off.

A 2,000 ft. drop-off.

I slowly picked my way forward through the rocks, stooping to crawl when I was too unnerved to walk. I knew that during the winter this ridge would have been even more dangerous, with snow blanketing it and creating a cornice, making it hard to tell what was ridgeline and therefore solid ground and what was only snow overhanging the drop-off to one side.

Finally I reached the end of the ridge, which opened up onto a gentle slope and the summit. In the distance I could see Chris. I made my way easily along his boot tracks to where he sat and lay down in exhaustion. I was too tired to eat. I lay there at 11,240 ft. and breathed in the air. I was on the rooftop of Oregon! After some minutes, I sat up and gulped down a liter of water. Chris then offered me a salami and cheese sandwich, which I greedily tore into.

![Mt. Hood summit]() Sloping summit plateau

Sloping summit plateau

It was a bluebird-sky day, and there was no one else with whom we had to share the summit. I tried to take in the views, closing my eyes as if to take a mental snapshot. I couldn’t believe where I stood, and I tried hard as I shut my eyes to forge in my memory a view I would never want to forget. Finally, I hoisted my ice axe into the air in celebration, and Chris was there to photographically immortalize my moment forever.

![Mt. Hood summit]() Me on summit

Me on summit![Mt. Hood summit]() Summit viewing trance

Summit viewing trance

After relaxing, goofing off, and taking some pictures, we sat up and got ready to go. It was time to get ready again. Getting up had been challenging, but I knew that I was only half-way to safety. The way down wouldn’t take nearly as long as the way up did, but we would find it just as mentally and almost as physically taxing.

![Mt. Hood summt ridge]() Summit ridge along descent

Summit ridge along descent

As we made our way away from the summit, the appearance of the treacherous ridgeline loomed in front of me once again. As I gazed at Chris crossing ahead, I told myself this would be the last truly hard part of the climb. Once again I carefully picked my way across, looking down at the steep drop-offs and down to the glaciers below. As I came across I realized the most challenging part was over, and I stopped to take a few last pictures from the top, this time looking down at the fumaroles from high above. I turned around backwards, facing into the slope, and began to down-climb step by step the steep 50 meters near the top. It was still solid ice, but it was heating up now, and I hoped the snow bridge across the crevasse would still be stable as well. We had to hurry to get down.

Later, while still descending, I met two guys a decade or so older than me who were on their own way to the top. As I stopped to talk with them, we talked about some of the ice climbing we had both done back

East and one of them asked me if this was the first time I’d been out west to climb a real mountain.

“Yes,” I admitted.

“Well, this is a hell of a way to start.”

“Thanks,” I said, as I plopped down on the snow to glissade for 2 hours through a constantly streaming path of billions of Monarch butterflies, which were embarking on an epic migratory journey---a journey that occurs over a few days time but only once every few years, but occurring in this year, on this day, in which they shared the mountain with us, on one beautiful, bluebird day in July.

![Mt. Hood Monarch butterflies]() Glissading down through a stream of Monarch butterflies. They were flying in a 3/4-mile wide swath across the mountain in a constant stream for over 2 hours.

Glissading down through a stream of Monarch butterflies. They were flying in a 3/4-mile wide swath across the mountain in a constant stream for over 2 hours.

Comments

Post a Comment