-

7918 Hits

7918 Hits

-

80.48% Score

80.48% Score

-

12 Votes

12 Votes

|

|

Trip Report |

|---|---|

|

|

19.02992°N / 97.26776°W |

|

|

Jan 15, 2015 |

|

|

Mountaineering |

|

|

Winter |

Starting Solo From the Hut

Like many other small steps in the progression to the peak, looking up the hill, pack shouldered, this registered as just one more Rubicon. My strategy so far was to keep going until I found a compelling reason to stop. I gulped, reaffirmed that yes, I was doing this and shuffled my feet up the old cement aqueduct that stands in for a trail above Piedra Grande. With 10 L of water and a brimming pack, climbing uphill was burdensome. After all the effort to get here in the company of passengers, the 4×4 driver and other climbers in the hut, I was finally setting off into the hills alone.The walk up the rubbly hillside held together by sparse bunch grasses was a pensive trudge under overcast skies. Where the aqueduct runs underground, the trail rounds a gentle ridge into a rubble strewn draw that runs straight up to the glacier and frames the peak in the V-shape of the valley walls. From this angle, the peak never seemed very distant. The featurelessness of the brilliant white glacier just over the horizon made scale and distance hard to gauge.

I set up my tent at the base of the Labyrinth. The 600 m elevation gain from Piedra Grande brought on a new round of grogginess. By the time the chirps from my GPS’s alarm brought me back from a fevered half-sleep at 02:00, my headache had all but passed. My misgivings had not. I spent most of the night wondering whether I was a rash lunatic to do the climb alone. My mood upon awaking was sharp and anticipatory and I figured I ought to at least scope things out before I threw in the towel.

I began taking stock of conditions as I set water to boil. Coming from my toasty sleeping bag, the air felt bitterly cold on my hands as I lit the stove outside through a crack in the zipper. There was a steady wind working its way around the mountain and I had to turn up the gas to get the stove to light, but once the flame of the lighter touched the rushing butane, the stove whooshed to light and I was off to the races.

Self Check: In some ways it is hard to assess if you are climbing impaired, but I relied on instincts based on the fairly intricate choreography of putting water on the stove to boil, divvying up the water into eggs, oats and instant coffee. I didn’t spill anything and got the proportions right, so I figured I was OK.

I was reminded that my body was in some form of shock when I had difficulty swallowing my freeze dried blueberry oatmeal---ordinarily a favorite. It wasn’t full-on nausea, just hard to get down the 1,200 calorie breakfast I usually wolf through when I’m through-hiking. I’d give it a 1: “loss of appetite” on the Lake Louise Symptom Survey.

Stay vigilant. I don’t think I would have attempted the hike had my headache persisted. You need your wits about you if your going to do the monotonous footwork you’ll need to perform consistently up the mountain for the next eight hours.

Gearing Up: I stripped out of the pair of long underwear I saved for sleeping and donned the sweaty ones from the day before, covered my feet I was protecting under my still-toasty sleeping bag with liner, then expedition weight socks and then donned thick fleece long underwear and a hoody top. The final layer was a pair of guide pants on the bottom and a 13 mm down sweater up top shelled by an old soft shell I’ve had in my closet for a hundred years.

I pulled boots out of a plastic grocery bag and tugged stiff laces to slip them over my numb, but recovering feet. Gaiters were the last item to go on and I was happy to take periodic drags from my hot coffee tumbler to keep my fingers nimble throughout the process.

Summit Bag: I hesitated before I unzipped my tent to the cold air, but as I swung my feet out the doorway, the view of the walls of the draw framed a blanket of clouds and the valley below illuminated by dim moonlight. I had to strike my crampons on rocks around the tent to clear them of frozen mud. I pried my ice axe up from the stiff silty grit left here by the terminal moraine, the dregs of chewed up boulders.

I paused to let my clothes warm up on my body and started piling supplies into my pack. I threw my heavier down coat (~37 mm loft), heavy gloves and liner gloves in. I took 4 L of water and came back with only 1 L, so I figure I gauged this correctly. I threw in my first aid bag and a splint, ropes and climbing hardware, camera, cell phone, nutrition bars, and that was about it.

The climb from high camp

I zipped my tent after one last moment’s hesitation about whether I’d packed the right stuff and flipped my GPS on as I started trudging the clear path up the floor of the draw. I glanced at the route I’d scouted the afternoon before on my GPS and clipped it to my pack strap.

There is a lot of advice on trip report sites about bearing left into the labyrinth, others suggest to stay right. At the end of the day getting there and looking at the climb while trying to recall which pattern to follow can be confusing.

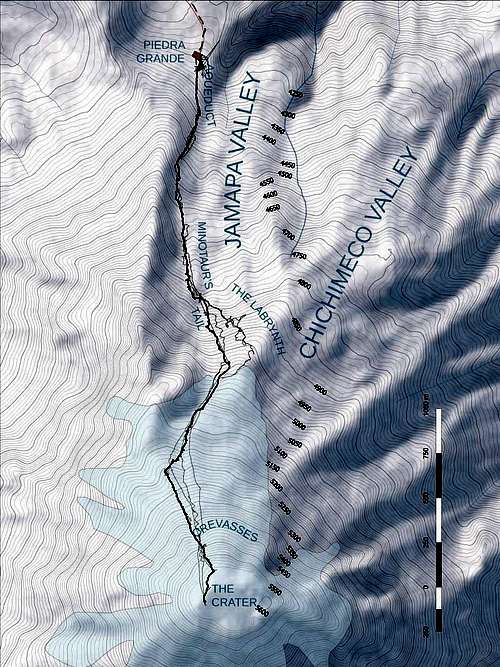

Looking up the draw. The Minotaur's Tail can be seen towering (photo left) and leads all the way up to the Gran Glaciar Norte

On my first summit bid I mistakenly tried to punch upward through the morass of rock outcroppings and irregular snow chutes of the Labyrinth and then still had to swing my axe overhead to gain purchase and pull myself over a 2 m headwall at the glacier. On my second attempt I got wise and ascended the way I had naturally descended the year prior through the wide straight couloir that leads all the way up to the Gran Glaciar Norte (no scrambling required).

Early routes in gray demonstrate how difficult the route bearing left into The Labyrinth is. Staying on the inside flank of the Minotaurs tail makes things much easier.

Cresting the lip of the glacier that first year, I was hit with a stiff wind carrying granita-like sleeting ice pellets that blinded me. The glimpses I caught under furrowed brow was of a moonlit snow plain hemmed in by rock shards and that ridge to the right that eased directly up to the cindercone. I walked for a minute or two more, bent on non-stop progress to the top before I caved. I dropped my pack to fish for my ski goggles and balaclava. I was still comfortable temperature-wise, so I held with just my down sweater---a decision I’d regret later. No longer needing the dexterity in my fingers, I swapped fleece gloves for my mountain mitts rendering the GPS a silent observer for the rest of the trip---they're hard to operate when you have your hands inside of diapers.

When I glanced up from refastening my backpack and panned my head as I swung my pack onto shoulders, I felt like a pilot in a cockpit. Every inch of my body was covered. In this most inhospitable environment, I felt... fine! I smiled as I took in the glacier and the lower part of the cinder cone lit by not much more than dim starlight, attenuated by the yellow tint of the goggles. I could make out the swinging beams of a couple who had pipped me for the lead with their wily no-breakfast gambit. They were ascending the ridge that reaches out to the Sarcofago directly. Red handkerchief waved, I set out on more of a traverse heading to where the ridge terminates into the caldera. While they were zigging and zagging, I charged straight ahead.

The perceived race to the top egged me on, but as I quickened my step, the couple stopped to eat. I turned and just kept trucking, now just racing sunrise for that amazing view of the mountain’s shadow cast onto the plains below.

The Monotony of the Glacier Climb: There’s a point along the glacier climb where having passed any and all landmarks that the trudge upward enters the doldrums. There are only 500 m between the top of the Sarcófago and the peak, but this ascent will take the average climber two hours. With no visual sense of progress it can seem sisyphean. Like walking up railroad tracks receding into an infinite V, the parallax–defying peak denies climbers much if any succor.

I’ve encountered both chopped steps and virgin snow on the glacier climb, but when you encounter switchbacks having to face the decision of taking a high road or a low road at every turn when you’re already gasping for breath can be a little agonizing if only for the repeated presentation of this temptation. The steep route or the gentler angle? Each time I thought, maybe I could take a break for a little while and walk the lower one... Needless to say, the progress seemed very slow.

I remember thinking, “Oh, I’ll just check my GPS”, but the readings gave a meaningless sense of progress. As you zoom out, you’re a dot somewhere in a series of nearly perfect bulls eye rings. Zooming in, you see that you’re at 5,230 m and 400 m from the crater as the crow flies. “OK, great, but how much longer?" Really who knows, the peak looks so distant in the dark and you probably won’t exactly be scampering uphill by the time you reach this elevation.

After the strenuous monotony of the climb, reaching the crater rim is a passive shock. Standing there on the rim, panting to catch your breath, the fearsomeness of the crater is one the most intense environmental experiences I’ve ever had. You can’t put out of your mind that there’s a vast hole hundreds of meters deep on one side and a effectively endless ramp on the other.

Moving up the uneven ridge at the crater. It's pretty intense to walk a ridge with an abyss on either side.

It’s not just the presence of the hole; the appearance speaks of a tremendous pandemonium written in crumbly remnants of molten rock columns and sulfuric scree. The reality looks like a freeze frame of something in the process of collapse, the jagged encrustation of ice lends the crater a wholly different timescale. Stone buttresses slump into the unstable void like pencils tossed into a cup. Walking in the midst of this inconceivable force is an incredibly humbling experience tempered by sense of achievement and the nearly omniscient perspective of looking out over Mexico as though you’re studying a map.

The ice clings to rubbly soil at the peak, evidently with a high sulphur and iron content. I didn't get close enough to the edge to see the bottom and don't think I'd want to.

Well, that's just the climb, but there are one-hundred-and-one little tricks to getting it done. I will be posting trip reports covering several aspects of climbing Citlaltépetl a.k.a. the Pico de Orizaba at several different summit sites: At 14ers, I’ve posted a trip report about how to travel to the mountain: 14ers.com/php14ers/tripreport.php?trip=16648. And I’ll talk about my experiences with people around the hut (it’s a lightning rod around Christmas break) at peakbagger. I'll post links soon or google me.

101 Tricks to a catastrophe-free climb on the Pico de Orizaba

Staying Found: I’ve analyzed every available report of accidents on the mountain 2010-2015 and as many trip reporters have suggested The Labyrinth really is the crux of the climb. The most common circumstance of accidents on Orizaba is becoming lost in The Labyrinth. Somewhere in excess of 3/4 of all casualties happen here.

Picking a route is something you need to do based on the conditions you’re dealt, but I believe the following advice could be made to work for most people most of the time: there is an enormous double-decker-train-car height hogback formation that separates the draw from The Labyrinth that I’ll call The Minotaur’s Tail. It runs all the way up to the Sarcofago, or in other words to the base of the Gran Glaciar Norte.

The Minotaur's Tail is exceedingly hard to miss, but if you don't have a GPS or good sense of the geography, consider waiting out the white-outs.

While visibility can drop to less than 3 m in inclement weather, The Minotaur’s Tail is very hard to miss and this alone will eliminate being “lost or wandering” that has been reported so frequently as the circumstance leading up to a casualty. Use the Minotaur’s Tail as the string to find your way through The Labyrinth to the straightforward glacier climb higher up.

You can climb to the right of the tail up to a point, but the way will eventually narrow to a shear wall at the Sarcofago. The couloir just along the left inside face could be an excellent option in certain conditions, but I’ve also climbed over the rocky formation itself in dry conditions.

I have annotated photographs, topo maps and 3-D drawings of the peak features within the free preview of a guidebook you can review here: http://amzn.to/1GdlbHp (just click "look inside", the route summary begins in chapter 2).

Walk Like an Egyptian: When the mountain is receiving snow, you aren’t as likely to run into the chopped staircase left by hundreds of climbers trodding over the same trail that you might find in dry December conditions. Learning a couple of the cramponing concepts from the "French technique" manual can go a long way to relieving strain on your calves. It looks like an ice skating turn and it made a night and day difference to climb using my gluteous maximus rather than prancing up a very steep incline on my tip toes for four to six hours. I write about it in my book, but Climbing has an excellent brief rundown. Yvon Chouinard's Climbing Ice is a book-length treatment of French technique and many other applicable topics to glacier climbing.

Pied a plat is no more, no less than a scissor-step. It sure beats tip-toeing on front points for four hours!

Maximize your Axe: At $35 Black Diamond’s mountaineering harness is twice what a store bought leash would cost, but being able to tie your axe in to a center point allows you to switch hands without messing with, untightening, changing hands and slipping a leash onto your other wrist all while wearing your mountain mitts. A 1 m runner worked just fine for my tall self. Larks head the runner through the eye in your axe head and clip in with a locking ‘biner or equivalent. However you do it, ensure you stay tied into your axe in some fashion. Two climbers in the accident reports I read died when they attempted to self-arrest only to have the axe stick and their body keep going. It’s an easy mountain, but you still have to follow basic safety measures.

A simple mountaineering harness. This one retails for $35 and allows you to switch your leading leg freely.

Four Waypoints that Might Save Your Life: I publish nearly 60 detailed GPS coordinates, times, distances and elevation readings in my route guide covering the entire route from Tlachichuca to the peak and back down to Coscomatepec along with detailed topo maps and route profiles. In the interest of getting you to the summit safely, here are the crucial four:

- #34 (681926 2107538, 639 M, 51M, 4,515 M): Kissing the ridge above the cirque.

- #38 (682055 2106789, 1.4 KM, 1H52M, 4,765 M): “The Portal”, a convenient break in the Minotaur’s Tail that allows you to traverse from the right-hand draw-side of the Minotaur’s Tail to the left-hand Labyrinth-side.

- #39 (682114 2106605, 1.6 KM, 2H52M, 4,845 M): “The Transfer”, a brief leveling out of the hogback where it changes angle slightly.

- #40 (682218 2106426, 1.8 KM, 3H52M, 4,970 M): The top of the Jamapa headwall where you’ll climb briefly over the relatively tame Chichimeco to start the the glacier climb in earnest.

NOTE: The UTM Zone is 14Q for all coordinates listed above.

Altitude Ailments: Finally, I’ve spoken about my own experiences with Acute Mountain Sickness in the narrative. This is something you need to stay vigilant about and educate yourself on how to avoid trouble. Reading the CDC page is a great start for blanket recommendations on staying safe. I’ve published some specific recommendations to Orizaba and done an in depth analysis, but at a minimum familiarize yourself with:

High Altitude Headache

Acute Mountain Sickness

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

The latter two, HAPE and HACE, are fairly rare but deadly if left untreated. They do occur on Orizaba as the plaque on the wall of the Octavio Alvarez hut attests. Complications typically arise from climbers denying their symptoms or becoming trapped by weather (unlikely on Orizaba).

Acetazolamide is the commonest preventative medicine for AMS. It can also be used to treat symptoms. Talk to your doc!

The way you diagnose these is by using the Lake Louise Symptom Survey (LLSS). Check out the printable version published by the UIAA here (see pg. 11). Should you experience any of these symptoms, rest in place. If they become severe or worsen while resting at the same altitude, DESCEND IMMEDIATELY! It is not complicated with Jeep roads leading down from the hut and it will save your life.

Wrapping up

I know some of these issues sound serious, but in my analysis, climbing Citlaltépetl during the typical season November-March and staying found has a similar risk profile to driving your car to work for a year. Come prepared with an awareness of the altitude illnesses you might experience, the proper clothing for the climb and quiet your mind with a familiarity with how to avoid the typical pitfalls. If you cover these bases, you'll be taking no greater risk than you would just living your life back home.

This climb, even out of some of the amazing hiking and climbing I've had the opportunity to do in Europe and the U.S. sticks out in my mind as learning lever and a hell of a good time. It calls to mind a Tim Ferriss principle about picking up a new skill by starting with the lowest risk / highest reward component and building from that. If you're interested at all in mountaineering, this has all of the components of a serious climb: altitude, climate and risk management, but it isn't terribly dangerous and the views and experience are just incredible.

For those who might be concerned about safety in Mexico, that's fair. If you haven't had your head stuck in the sand for the past ten years, there is this thing called "The War on Drugs", and it's currently being fought along the border with the United States. The term 'war' is not euphemistic as the 100,000 dead from the drug war roughly approximate the numbers from the U.S.'s most recent foray into Iraq. To paint the entire country a no-go zone would be extremely crude. The violence is concentrated in border states where trafficking occurs. Mexico City has a lower murder rate than Chicago and the number of U.S. tourists that come back from Mexico dead is half the murder rate in the United States. In other words, statistically, you're safer traveling.

An extended family visiting taking a "walk in the woods" up to Piedra Grande over Christmas break picked me up in their off duty colectivo on and drove me into Coscomatepec.

Aside from these somber subjects, Mexico is just a hell of a lot of fun. Three course dinner with drinks for $25? You bet! And were not talking tacos or burritos, the cuisine in Puebla recently was awarded UN Cultural Heritage status. You can try rich moles, some crazy grasshopper dishes (if that turns you on--I developed an affinity for chapulines, but to each his own).

There's a nascent craft brewing thing going on and Mexico is also working hard to promote their vineyards. They haven't caught up to California yet, but the wines are unique and interesting. The reason wine never made a showing is because their former mercantile master, Spain, then France didn't want competition, rather consumers for exporting their own wine, which drove Mexicans to invent their own spirits: pulque, Mezcal, and Tequilla, all derived from agave that you'll see growing wild all over the country.

The rooftop cafe at the Museo Amparo in Puebla affords amazing views out over the campaniles of the city's cathedrals. The food here is a gastronomer's delight.

I haven't gotten to the beaches yet--if you decend to lower altitudes you'll find sweltering 85º F / 32º C temperatures on the Pacific beaches of Oaxaca in January. Veracruz is a 2-1/2 hour bus ride from nearby Cordoba... don't get me started. It's a hell of a trip!

Mountains meet the sea in coastal Oaxaca. The lush mangroves of Lagunas de Chacahua National Park abut a secret surf spot (3+ m waves).

Stay in touch! I wrote a guidebook and I'd be happy to answer any questions you may have on your trip planning, climb or any other aspect of this AWESOME peak. I value your feedback. I can be found on twitter @antivoyage and will be setting up a website in the coming weeks.

Safe climbing,

-A