-

12832 Hits

12832 Hits

-

85.36% Score

85.36% Score

-

20 Votes

20 Votes

|

|

Mountain/Rock |

|---|---|

|

|

36.93740°N / 121.1553°W |

|

|

Merced |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

2682 ft / 817 m |

|

|

Overview

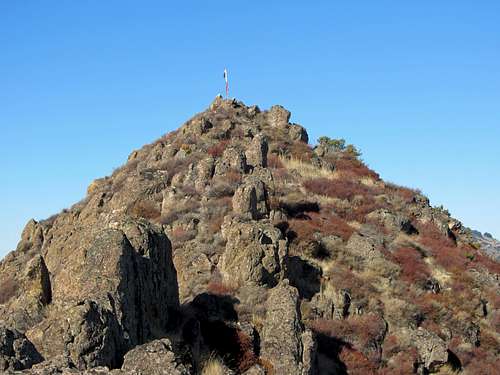

Twin Peaks North is one of the most inaccessible as well difficult peaks to climb in the entire Diablo Mountain Range. Not only is it deeply isolated on private ranchlands, but to reach the summit involves tricky route-finding and scrambling up steep, rocky slopes that often rise dramatically into sheer vertical cliffs.The peak is located in western Merced County east of the Diablo Crest, approximately 23 miles southwest of Los Banos and 22 miles northeast of Hollister. It occupies land once part of the original 22,175-acre Mexican land grant Rancho Panoche de San Juan y Los Carrisaltos which had as its northern boundary Los Banos Creek. The area has long been known for its colorful ranching history that dates back to the time of Alta California. And today is no exception as the area is still entirely surrounded by cattle country. The peak is also located just a few miles east of the historic Stayton Mining District where quicksilver was mined up until the 1940’s, and is located within the borders of the Quien Sabe Volcanic Region, a 100 square mile area of unique volcanic features which have been the subject of multiple geological studies.

Twin Peaks North occupies the center of a hidden valley from which the North Fork of Los Banos Creek drains eastward. Nearby peaks and ridges such as Beckham Ridge, Mount Ararat, Antimony, Mariposa and Cathedral Peaks (all closer than 4 miles distance) surround and look down upon it from heights as much as 1000 feet higher on all but its eastern side. But yet seen from any of these points, one is struck by the imposing features with which Twin Peaks North dominates its surrounding landscape: for instance, 742 feet of prominence, much of it gained by naked cliffs that slice upwards and culminate abruptly into a massive summit block of barren volcanic rock.

Routes

The southwest, west and northwest sides of Twin Peaks North have sheer, vertical cliff-faces that appear to involve class 5+ climbing. The north and northeast sides have routes that rate from class 3 upwards. One can expect to find unstable handholds and footing on these routes as well an increase in difficulty due to a preponderance of rotten rock and a buildup of loose dirt and moss along ledges and between rocks. The easiest route is the eastern ridge which is class 2 provided one circumvents short cliff-faces and sizeable outcrops that randomly bar one’s path. Upon reaching the summit you’ll find it to be a fairly broad matrix of scattered sagebrush and ancient lichen-covered boulders of various sizes.Summit

Due to its height within the valley, Twin Peaks North has a wide field of vision in all directions. Twin Peaks South is its closest landmark. Further south, slopes interspersed with sagebrush and chaparral rise towards Beckham Ridge which at its western end reaches a height of 3717 feet. Laveaga Peak is the impressive county highpoint seen on the more distant southern horizon. To the north, less than one mile and 1700 feet below, rolling hills of grass and sagebrush rise from the North Fork of Los Banos Creek towards 3274 foot Mount Ararat. Four miles northwest, the south-facing cliffs of Mariposa Peak appear, as well, an abundance of rough, volcanic outcrops below Cathedral Peak. To the east low, treeless hills and nameless arroyos undulate and recede off into the San Joaquin Valley flat-lands.Getting There

From the San Luis Reservoir Off Highway Vehicle parking area follow Jasper Sears Road south up a gentle incline. The paved road turns to gravel just before it passes over a gated cattle-guard. Continue to the junction with Billy Wright Road which heads southwest. Use googlemaps.com and/or the Los Banos Valley USGS quadrangle to familiarize yourself with the road junctions and landscape. At the 6- mile mark Billy Wright Road stops abruptly at a locked gate with a “private-property, no trespassing” sign posted above it. When and if permission is granted, continue traveling east. The road eventually parallels the North Fork of Los Banos Creek. At the 12.6 mile mark you are in a position to follow a separate jeep trail south as it skirts the northeast perimeter of Twin Peaks North. The jeep trail gradually gains in elevation and in less than one mile arrives at a point from which to ascend the peak’s east ridge.West Side Trails and Pacheco Pass

Where the foothills of the Mount Diablo Range meet the western edge of the San Joaquin Valley, El Camino Viejo, the westside trail from San Pedro to San Antonio (now in Oakland), crossed El Arroyo de Ortigalito (“little nettle”), a link in the long chain of arroyos and aquajes (water holes) where Indians had settled for ages. From the water holes at Ortigalito, El Camino Viejo proceeded northwest to El Arroyo de los Banos del Padre Arroyo, where fresh water was again found. Still farther to the north the road crossed El Arroyo de San Luis Gonzaga at Rancho Centinela, where another water hole was found 50 yards to the north. Leaving Centinela, El Camino Viejo skirted the abrupt foothills that led to El Arroyo de Romero, named after a Spaniard from San Juan Bautista who was killed there by Indians. Finally, El Arroyo de Quinto (“fith creek”), the last watering place in Merced County was reached. An adobe, perhaps built before 1840, stood on the plains among the cottonwoods of Quinto Creek as late as 1915.With the coming of the Americans and the growth of transportation from Stockton to points south, the Stockton-Visalia Road was developed parallel to El Camino Viejo. It followed the west side of the San Joaquin River, the route varying according to the seasonal changes in the river country. The one-story adobe at San Luis Camp on Wolfson Road, seven and one-half miles north of Los Banos via Highway J-14, was once an important low-water station on this road. Neglected for many years, it has been protected from the elements by an overhanging roof. This adobe and other structures built in the early 1840’s came under the control of miller and Lux; Henry Miller customarily slept in the house whenever he visited this part of his property.

Joining the Stockton-Visalia Road eight miles northeast of Los Banos, the older Pacheco Pass stage road came in from the west. Long before the Americans came, Indians had worn a deep trail over the hills by way of Pacheco Pass, and Spanish explorers, as well as Spanish officers in pursuit of deserting soldiers or runaway mission Indians, made use of this old mountain path.

A toll road was built over the Pacheco Pass in 1856-57 by A.D. Firebaugh. Two miles west of the summit (in Santa Clara County), and a mile from where the Mountain House later stood, he built a toll station. Portions of the old rock walls of the tollhouse may still be seen in the narrow defile below the present highway.

The early stage road was used by the Butterfield overland stages from 1858 to 1861; on it San Luis Station was an important stopping place. It was eighteen miles from San Luis Ranch east to the Lone Willow Station, and from there the stages passed through a long stretch of desolate alkali wastes to Temple’s Ranch and on to Firebaugh’s Ferry in Fresno County. During the middle 1860s the loneliness of this part of the road was relieved by the cabin of David Mortimer Wood at Dos Palos. There, a lantern was placed in the window at night to guide the drivers of the Gilroy-Visalia stages. Water for the horses was available, too, and in return Wood received supplies and mail brought by the stagecoaches. The part of the old road that lay between Los Banos Creek and Santa Rita ran about one mile and a half north of the present highway SR 152, which was completed in 1923. Along it were the earliest pioneer American settlements of the Los Banos district. Very little remains to mark any of these places except an occasional black and gnarled tree or faint traces of the former roadbed.

Pacheco Pass is now SRL 829; the state marker is at the Romero Overlook above the San Luis Reservoir. A branch of the Pacheco Pass Road crossed El Camino Viejo at Rancho Centinela. From this point it continued northeast to the ford of the San Joaquin River where Hill’s Ferry in Stanislaus County was established in the days of the Gold Rush.

[Mildred Brooke Hoover, Douglas E. Kyle, Historic Spots In California, 5th Edition, (Stanford University Press, Stanford California 2002), pgs. 211-212]

History of Merced County-Early days on the Westside

The Pacheco Pass appears to have been a way through from the Santa Clara Valley quite early. How early it received the name in now bears hard to say, but in view of the fact that Juan Perez Pacheco was one of the grantees of the San Luis on November 4, 1843 it seems reasonable to assume that the name was probably applied to the pass as early as the forties. It appears to have been the way across which the indefatigable Gabriel Moraga passed on more than one of his numerous expeditions against the valley Indians from 1806 on, though we gather no hint that the pass then enjoyed the dignity of a name.One of the first petitions which was presented to the board of supervisors of the newly organized Merced County, in 1855, was one by A. Firebaugh for permission to build a toll-road across the pass. Firebaugh, in conjunction with others, some of them at least in Santa Clara County, planned and built a road from San Jose across the pass. We find through the minutes of the board of supervisors during 1855 and 1856 that they extended Firebaugh’s time at several different meetings, for the completion of the road.

Two writers of note have recorded the fact of crossing the pass rather early—both in the sixties, in fact. Clarence King tells of doing so in his “Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada,” about 1864; and John Muir, in “My First Summer in the Sierra Nevada,” gives an account of crossing it in April, 1868. Neither of these writers has anything to say of the inhabitants; but it is well to read Muir especially as an antidote to the impression of the country as something approaching a desert, which may be suggested by our attempt to guess the impressions it probably made on Gabriel Moraga and his men on the occasion, late in the year, when they left a permanent record of their thankfulness in finding the Merced by naming it “River of Our Lady of Mercy.” Such men as John Montgomery, John Ruddle, and Colonel Stevenson early recognized the East Side as a desirable cattle country, and drove in cattle from the States; and Henry Miller found the place he wanted on the West Side. A well-informed stockman made the statement in 1924 that there were more cattle shipped annually from within a radius of twenty-five miles of Merced than from any other equal area in the world; in that year Merced County had over 80,000 stock cattle and over 40,000 dairy cattle, and was surpassed among the counties of the State only by Kern in number of stock cattle and Stanislaus in number of dairy cattle. It raises also large numbers of sheep, and a considerable number of hogs.

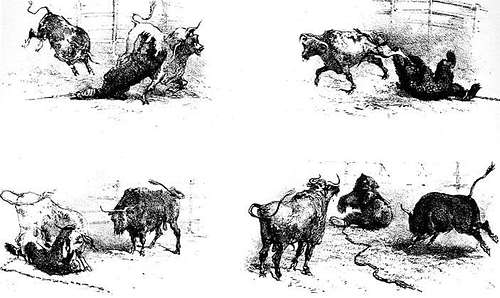

One reminiscence of Mr. Stockton, which he must necessarily have had at second hand, recalls Grizzly Adams’ story of the stock-killing grizzly. It relates that a stockman named Davis, on the West Side in the early fifties, witnessed the killing of three grizzlies one after the other by a bull, and conceived such a respect for the bull as a fighter that he took it to Stockton, where fights between bulls and grizzlies were a feature. There, says the story, the bull was matched against a grizzly which had something like seven bulls to its credit, and the bull killed the grizzly, and piled up a record of almost a score of bears, until the brutal promoters, finding they could get no more matches, hamstrung the champion and let a grizzly kill him. This barbaric sport had a short life in the State; it was soon prohibited on account of its cruelty.

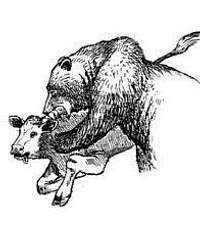

The San Luis Ranch House was a station on the stage route between San Jose and Visalia pretty early. S.L. Givens mentions the stage stopping there in 1858, when he was a boy going to college at Santa Clara. James Capen Adams (“Grizzly Adams”), who hunted and captured grizzlies on the upper Merced during the fifties and late in that decade exhibited several of these and some other animals in San Francisco, and whose life story was written in book form by Theodore Hittell, evidently passed along the West Side of this county in the later fifties, and he tells of a grizzly coming out of the bushes somewhere in that vicinity and rolling on the ground to excite the curiosity of the cattle until one came near enough for the bear to kill it. Adams was apparently not concerned about county lines and could not probably have distinguished them, but we get from him the idea of the West Side as a stock country with a few scattered ranch houses.

W.J. Stockton came to the West Side in October, 1872, and Charles W. Smith in 1874, and to these two pioneer residents of that section we are indebted for much information about early days there. “When I first came to Los Banos,” says Mr. Stockton, “I hauled timber across the old Toll Road from Gilroy to build me a house. It took me about a week to haul one load—and such a road! Sometimes we used to tie a log on to the back of the wagon with a rope to act as a brake, the road was steep.”

The West Side, when Mr. Stockton arrived, was a country of a few large stock ranches for cattle and sheep, as the big grants would indicate. Back in the hills on the east slope of the Diablo Range, there was a population, he estimates, of 400 or 500 people of Spanish or Mexican blood. They appear to have lived on ranchitos and to have kept a few head of stock, including of course the ever necessary saddle horses, raising, we may imagine, their frijoles and chilis, getting their wood and their venison from the country, and finding employment in season at the rodeos and sheep-shearings on the large ranchos. There were some very large families of them; the Alvarados, up near the head of Los Banos Creek, had nineteen children, and there were the Soto, Pio, Gonzales, and Merino families, to name only a few.

[John Outcalt, Merced County California History. (Historic Record Company, Los Angeles, California 1925) Chapter XII: Early days on the Westside, pgs. 217-219.]

Grizzly Adams on the Westside in Merced County

That evening we camped in a ravine at the foot of the mountains, in the neighborhood of large herds of cattle, which were grazing in the plains. The herdsmen, or vaqueros, when they saw us, came up and talked awhile, and then proceeded further up the ravine to their ranch, leaving the cattle to themselves. About sundown I heard a tremendous commotion among the cattle, and, going out to see what caused it, beheld a huge grizzly bear rolling and tumbling in the grass, while the cattle were gathering around him, and bawling as if crazy. I immediately took my rifle and went around in such a manner as not to disturb either cattle or bear,—my object being to get up near and witness the motions of the bear, which, I correctly supposed, was playing one of the most wonderful tricks known to his species. I had frequently heard of the sagacity of the grizzly in decoying cattle within his reach, and had a great curiosity to see it for myself.I accordingly ascended a small hill near the spot, and reached a place from which I could easily witness the whole affair. The bear was in the long grass, rolling on his back, throwing his legs into the air, jumping up, turning half somersets, chasing his tail and cutting up all kinds of antics, evidently with no other purpose than to attract the attention of the cattle. These foolish animals crowded around him; some bulls running up as if to make a lunge, and then turning aside, and all bawling violently. At last a young heifer, more bold than the rest, lowered her head and ran up, to thrust her horns into him. In an instant the bear rose upon his hind legs, and, making a leap caught the heifer around the neck, and fixed his jaws in her nose. She made a jump to get away; but the bear, with a peculiar jerk of his head, threw her upon her side, and, without loosening his hold, turned his entire body upon her. He then let go his hold upon the nose and seizing her by the neck, tore it open; the blood gushed in torrents from the severed arteries; and in a few moments she was dead. No sooner had she stopped struggling than he got off, and leisurely began sucking up the blood, and enjoying the supper which his trick had procured for him.

The other cattle drew back at first, but in a short time they seemed to gather courage, and again approached. As they came close, the bear left his victim and rushed at them with a terrific growl. This frightened them off for a while; and then the bear would resume his meal. He drove them off thus a dozen times; and I relished the scene so well that, without interfering, I lay looking at it until it became quite dark,--thus neglecting the opportunity to have a fair shot at him. As he was about turning to leave, however, I crawled down and fired at him; but it was then so dark, and the distance so great, that I missed. At the crack of the rifle he rose upon his legs, uttered two or three savage growls, and then put off for the mountains.

In the morning I sent Drury to the ranch to give information of what I had seen; and in a short time he came back with the vaqueros and two of the ranch owners. I told them the story, and they seemed much interested. They said they were much troubled with bears, and offered to give me one hundred dollars a month and all the beef I wanted, if I would remain and hunt there a few months. I laughed at the proposition, and replied that a gold-hunter on his way to Kern River could not be purchased on terms like those. They laughed in turn about Kern River; and, after talking in good-humor some time, I took a portion of the dead heifer with their consent, and, bidding them good-bye, proceeded on my journey. [Theodore H. Hittell, The James Capen Adams Mountaineer and Grizzly Bear Hunter of California. (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1911) pgs. 315-317.]

William Brewer on the Westside in Merced County

I had not spent a day in camp, save Sundays, since leaving Diablo, so Wednesday, June 18, I resolved to stay in camp, write, wash, and do odd jobs. It was still hotter—above 100 most of the day, and 87 after eight o’clock in the evening. With a fresh breeze it stood at 102 for hours, and so dry that heavy woolen clothes after washing were perfectly dry in less than two hours. It may have been sooner. I looked in two hours after leaving them out and found them dry.Well, I washed my clothes, a job I positively hate—I would rather climb a three-thousand-foot mountain—and to make matters more aggravating, just as I was in the midst of it, along came two women, one young and quite pretty, who were assisting as vaqueros. A rodeo took place near camp, and several thousand head of cattle were assembled, wild almost as deer. Of course it takes many vaqueros to manage them, all mounted, and with lassos. A rodeo is a great event on a ranch, and these women, the wife and daughter of the ranchero came out to assist in getting in the cattle. Well mounted, they managed their horses superbly, and just as I was up to my elbows in soapsuds, along they came, with a herd of several hundred cattle, back from the hills. I straightened my aching back, drew a long breath, and must have blushed (if a man can blush when tanned the color of smoked bacon) and reflected on the doctrine of Woman’s rights—I, a stout man, washing my shirt and those ladies practicing the art of vaqueros.

The cattle were “marshaled,” in a close body on the plain near, with hills on either side, surrounded by vaqueros on horseback. The rancheros from adjoining ranches were on hand to select such cattle as belonged to them and get them out. A rodeo is always a spirited scene. The incessant “looing” of these three thousand cattle, the riding, the lassoing, etc., form a scene that an eastern farmer cannot well conceive from description. This is considered a fine stock ranch—several thousand head of cattle and hundreds of horses are kept.

Thursday, June 19, we raised camp and came on to camp 77 at Ranch San Luis de Gonzaga, at the eastern end of Pacheco’s Pass, twenty-seven miles—twenty-four of which were along the plain—with a temperature all day of 95 to 102. Before entering the pass, we struck a road—a mere trail, yet it was a road, and what a luxury! We trotted our mules gaily along it. It is a novelty, for we saw our last road three weeks ago!

We camped in a very windy place. A strong current of air pours over Pacheco Pass the entire summer—from the west, cool, to supply in part the demand of the hot San Joaquin plain—and we were camped directly in this channel.

Friday, June 20, we climbed a peak nine or ten miles south of camp, a conspicuous point, from which we had a prospect of a large extent of very rough country and a very great extent of plain beyond—a long and laborious day’s work.

In crossing some of the ridges that lay in the channel of this great wind current over the depression here in the mountain chain, the wind was so intense that our mules at times were blown out of the trail several feet—they could scarcely stand. The oak trees often lay along the ground, in the direction of the wind. They were not uprooted, but had grown in that way in that perpetual wind.

Saturday, June 21, we climbed another peak, about eight miles northwest—nothing of especial interest. Sunday was a quiet day in a windy camp. I wrote for some time in the tent, but at last the wind grew too high for that. We took a pleasant swim in a stream near, the first swim for the season. That night was the windiest we have had this season. We had to pile saddles, stones, anything heavy, on our blankets while we crawled in them, yet the wind would blow through them.

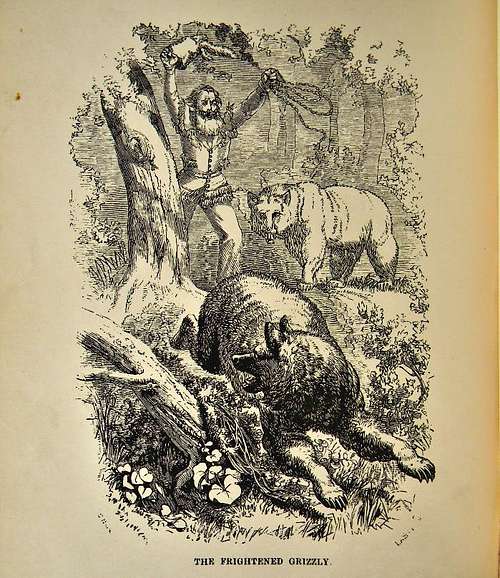

Monday, June 23, I visited some hills alone, and sent Gabb and Hoffman on a longer excursion back, with the mules. The event of the day was their meeting, in a narrow ravine, a large she-grizzly with a cub. Now this is the worst kind of a customer to meet, and as they came upon her very suddenly, matters did not look well. She faced them at first, scarcely thirty feet distant, then slowly retreated. They took the hint, and both parties escaped unharmed; the two bears leisurely climbing the steep bank of the ravine on one side, the geologists climbing, less leisurely by far, the steep bank on the other side

[William Brewer, Up and Down California in 1860-1864: The Journal of William H. Brewer. (University of California Press, Berkeley 1966, 1974) pgs. 285-287.]

Historic Account of Bull and Grizzly Bear Fight

“War! War!! War!!!The celebrated Bull-killing Bear,

GENERAL SCOTT,

will fight a Bull on Sunday the 15th inst., at 2 P.M.,

At Moquelumne Hill.

“The Bear will be chained with a twenty-foot chain in the middle of the arena. The bull will be perfectly wild, young, of the Spanish breed, and the best that can be found in the country. The Bull’s horns will be of their natural length, and ‘not sawed off to prevent accidents.’ The Bull will be quite free in the arena, and not hampered in any way whatever.”

The proprietors then went on to state that they had nothing to do with the humbugging which characterized the last fight, and begged confidently to assure the public that this would be the most splendid exhibition ever seen in the country.

I had often heard of these bull-and-bear fights as popular amusements in some parts of the State, but had never yet had an opportunity of witnessing them; so, on Sunday the 15th, I found myself walking up towards the arena, among a crowd of miners and others of all nations, to witness the performances of the redoubted General Scott.

The amphitheatre was a roughly but strongly built wooden structure, uncovered of course; and the outer enclosure, which was of boards about ten feet high, was a hundred feet in diameter. The arena in the centre was forty feet in diameter, and enclosed by a very strong five-barred fence. From the top of this rose tiers of seats, occupying the space between the arena and the outside enclosure.

As the appointed hour drew near, the company continued to arrive till the whole place was crowded; while, to beguile the time till the business of the day should commence, two fiddlers—a white man and a gentleman of color—performed a variety of appropriate airs.

The scene was gay and brilliant, and was one which would have made a crowded opera-house appear gloomy and dull in comparison. The shelving bank of human beings which encircled the place was like a mass of bright flowers. The most conspicuous objects were the shirts of the miners, red, white, and blue being the fashionable colours, among which appeared bronzed and bearded faces under hats of every hue; revolvers and silver-handled bowie-knives glanced in the bright sunshine, and among the crowd were numbers of gay Mexican blankets, and red and blue French bonnets, while here and there the fair sex was represented by a few Mexican women in snowy-white dresses, puffing their cigaritas in delightful anticipation of the exciting scene which was to be enacted. Over the heads of the highest circle of spectators was seen mountain beyond mountain fading away in the distance, and on the green turf of the arena lay the great centre of attraction, the hero of the day, General Scott.

He was, however, not yet exposed to public gaze, but was confined in his cage, a heavy wooden box lined with iron, with open iron-bars on one side, which for the present was boarded over. From the centre of the arena a chain led into the cage, and at the end of it no doubt the bear was to be found. Beneath the scaffolding on which sat the spectators were two pens, each containing a very handsome bull, showing evident signs of indignation at his confinement. Here also was the bar, without which no place of public amusement would be complete.

There was much excitement among the crowd as to the result of the battle, as the bear had already killed several bulls; but an idea prevailed that in former fights the bulls had not had fair play, being tied by a rope to the bear, and having the tips of their horns sawed off. But on this occasion the bull was to have every advantage which could be given him; and he certainly had the good wished of the spectators, though the bear was considered such a successful and experienced bull-fighter that the betting was all in his favour. Some of my neighbors gave it as their opinion, that there was “nary bull in Calaforny as could whip that bar.” Continue reading this account here.

[J.D. Borthwick, Three Years in California, (William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London 1857)pgs. 290-292.]

Driving Directions

East Access: Traveling south on Interstate 5 take the Santa Nella exit and follow Santa Nella Road 3.5 miles south to Gonzaga Road. Turn right and drive .5 miles to Jasper Sears Road where you can only go left. Immediately turn left into the San Luis Reservoir Off-Highway-Vehicle, day-use parking area. There is a $3 self-pay fee. Restrooms are available.West Access: From Highway 101 exit in Hollister then connect to highway 25 and drive east to either Comstock or Lone Tree Road and then find a suitable place to park.

Camping

Motels are available in nearby the nearby towns of Los Banos, Gustine and Newman. There are a number of campgrounds at San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area. Basalt Campground is perhaps the best choice as it is located within day-hiking distance of Twin Peaks North and South, albeit a long-day hike.Red Tape

Twin Peaks North and South are located on private property, you will need permission from property owners to hike here.External Links

Twin Peaks North on Listsofjohn.comList of Merced County Peaks and Highpoints

Topo Map of the area

Additional Photos

Bob Burd - Oct 14, 2013 2:33 pm - Voted 10/10

Billy Wright RdThis was sent to me by Murphy Mack via email. Apparently the approach via Billy Wright Rd is a public easement. I doubt the peak itself is part of the easement, however. I have spoken with Merced County public works (roads) and they have told me that Billy Wright Rd. in Merced County, control of this was ceded from the county to the ranch owners there. However, part of the agreement was that a public easement be maintained. I went to their office and got to check out a key to the gate. When I arrived, it turns out the gate is just dummy locked anyway. Two other people in cars there both smiled and waved at me as they passed going the other way.