-

71397 Hits

71397 Hits

-

97.55% Score

97.55% Score

-

70 Votes

70 Votes

|

|

Route |

|---|---|

|

|

46.57456°N / 7.99444°E |

|

|

Mountaineering |

|

|

Summer |

|

|

One to two days |

|

|

5.3 (YDS) |

|

|

Assez Difficile |

|

|

II |

|

|

LOOKING BACK – some history by hansw

First ascent by a dog

As the rocks became difficult the aunt and nephew left her to guard the knapsacks. But about half-way up the bad rocks she was seen coming after. For the final ascent and for part of the descent she was roped. Although bleeding profusely in each of her paws she led the way over rocks and ice avoiding every crevasse. In short she was a born guide.

She was the amazing beagle Tschingel who together her owner alpine historian W.A.B. Coolidge and his aunt Meta Brevoort climbed the Eiger in 1871. Tschingel was given to Coolidge by Christian Almer, being possibly the greatest of the early Alpine guides. Almer has many first ascents to his name also including the Eiger by the West Flank. In 1858 he and his colleague Peter Bohren known as the “Glacier Wolf “ stood on the summit together with an Irishman named Charles Barrington.

Early (human) ascents

As above, the first ascent was made by the guide (& original owner of Tschingle) Almer, his colleague Bohren and client Barrington. See First Ascent of the Eiger 1858.

The second ascent came on July 27, 1861 when doctor Porges from Vienna was led to the summit by Christian Michel and Hans and Peter Baumann. Starting from Wengernalp at five in the morning they reached the summit eleven hours later at four in the afternoon. On their descent they spent a cold night under a clear sky on a rock before returning to Wengernalp the following day. Porges was exhausted and needed long medical treatment before he was able return to Austria.

The third ascent of the West Flank took place one year later on July 26, 1862. The Englishmen J. S. Hardy and R. Liveing and the guides Christian and Peter Michel and Peter Inäbnit also started from Wengernalp as early as 1.30 in the night and had almost 2000 hard meters to climb before they could stand on the summit at four in the afternoon. They returned unhurt at eleven the same evening. The West Flank was now established as the normal ascent route of the Eiger.

The first woman

Lucy Walker from England became the first women to climb the Eiger. Together with her guide Melchior Anderegg she reached the summit on August 23, 1864. The first winter ascent along the West Flank was made in January 7, 1890 by the Englishmen Woodroffe and Mead, together with the guides Ulrich Kaufmann and Christian Jossi.

First record descent

Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler climbed the Eiger North face in 1974 using 10 hours, by then considered an incredibly fast ascent. Impressive was also that it took them less than two hours from the summit to the hotel at Kleine Scheidegg, about the time it takes today for the fastest of to climb the North Face (sic!). There is reason to believe that the record time to descend the West Flank has been reduced considerably since days of Messner and Habler.

Main reference: Über Eis und Schnee – Die höchsten Gipfel der Schweiz by Gottlieb Studer, 1896 (in German).

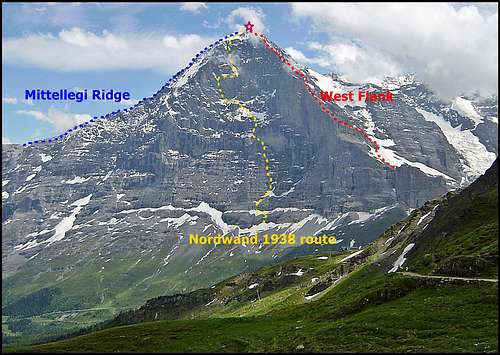

OVERVIEW

The Eiger West Flank was the route of the original ascentionists, as well as traditional descent route for successful (surviving?) parties coming down from the summit having climbed the infamous Nordwand - a.k.a Murdewand (‘Murder Wall’).

This western route isn’t so popular now. These days most guided parties are ascending the Eiger via the Mittellegi (East) ridge and descending via the South ridge. A few parties still descend the West Flank, having ascended via the other routes. As for parties actually wanting to ascend the route – seemingly these are a dying breed. But I should point out that I am one of them, that I am one of these Eiger Dinosaurs – and I actually like the Eiger West Flank.

I have to admit though, that as an Alpine route, the West Flank does have its minus as well as plus points.

Plus points

It is an historic route to the top of one of the most striking and famous mountains in the world. Right at the very heart of the Bernese Oberland the route commands extraordinary views of the shining giants of Monch and Jungfrau, as well of the meadows of Kleine Scheidegg and forests of the Grindlewald valley.

More of an acquired taste, the route also provides, at regular intervals, increasingly startling insights into the shadowy abyss of the Murder Wall. (Having peered over the top of this from Pt 3668m in 2008, I concluded this was something better appreciated from a safer distance – but that is just me).

The route is one of a handful of alpine ascents that completely avoids glacier – and is thus suitable for the solo alpinist. My own experience of the route in 2008 was solo - as was a later and successful ascent by Jordonj - beautifully described in his trip report Desert In The Sky.

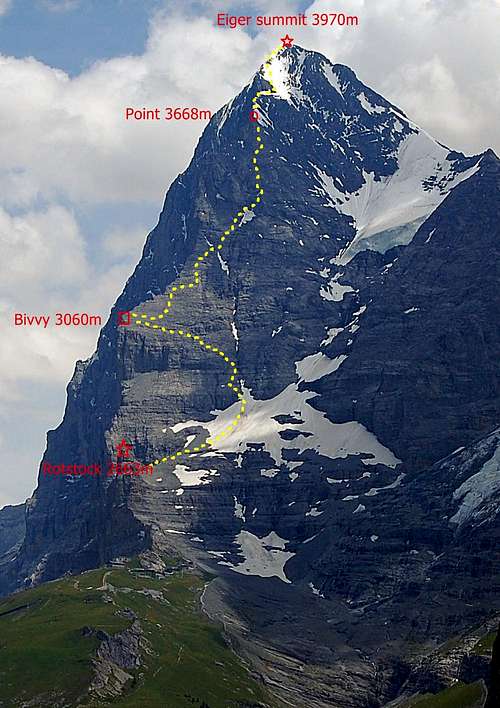

In terms of the difficulty, quality and danger of the climbing the route is comparable to the Hornli Ridge of the Matterhorn, but longer. An important difference is that there are no crowds – very few are likely to be on the route at any given time. In July 2008 I was on the route a total of 3 days: I explored the route to 3060m, turning back due to deterioration in the weather. But then I returned and bivvied at 3060m before climbing up to a high point of 3668m – and then descending all the way back down to Kleine Scheidegg. In all that time I saw just one pair of climbers who had completed one of the shorter routes on the Nordwand, emerged on the West Flank – somewhat dramatically at sunset – and then trotted down past my bivvy site. The next day, when I made my summit attempt, I didn’t see a soul.

Whatever is said about the quality of the climbing on the Eiger West Flank, the route is definitely a challenge. This part of the mountain is so big; it is in my opinion, an alpine face in its own right. Particularly in descent, it calls for stamina, route finding ability and skills in being to move quickly and safely over varied, loose and steep terrain.

Many would be-moan the fact that the route has no Alpine Hut and that from the very base (where there is some limited accommodation) to the top is a punishing 2000m of ascent. To me personally this is a plus, since it means the route is ‘quiet’ – without the queues of the Hornli Ridge. But I am not into 2000m ascents either... so I’d suggest break the route with a bivvy.

There is a good bivvy site at 3060m – see ‘Eiger Hilton’ below.

A further suggestion for a memorable 2 day alpine excursion is as follows: with nothing less than an excellent weather forecast set out from Kleine Scheidegg (Eigergletscher Station if you insist) in the late afternoon (after an excellent lunch in one of the restaurants). Climb the Via Ferrata (Klettersteig) route ascending the Rotstock and as the sun sets, climb on up the lower part of the West Flank – up to the bivvy site at 3060m. Being west facing this is a superb place from which to observe the sunset. Then in the morning, an early start can be made on the remaining 900m of ascent to the top.

Minus points

The British Alpine Club 2003 edition of the Bernese Oberland guide-book (by Les Swindin) is very negative about the route, saying that it is ‘not one of the good climbs’ and that it is ‘like a tiled roof covered in debris’...

Hmmm – well yes, I suppose it is – and a very big tiled roof and all. The West Flank is one massive crumbling piece of real estate.

The reason it is like a tiled roof is that the quite unique Eiger rock is composed of slatey strata which dips downwards towards the north and west – hence like roof tiles, overlapping each other. And most of this rock is brittle and poor quality – which explains the ‘covered in debris’ bit. The only saving grace is that it isn’t vertical – other than the odd short step. (But spare a thought for the Murdewand, where much the same sort of stuff IS vertical – and even overhanging in places).

It is a little un-nerving going up the stuff – but downright hazardous coming down. The downward dipping rock plates are quite slick even when dry – but add a layer of splintered Eiger-shale – well, it behaves a bit like a layer of ball-bearings. Banana skin moments are a harsh reality. Not that there are many places on the West Flank where you are likely to plummet for 100’s of feet – but you can be injured quite enough dropping 10-20 feet. Fatalities have occurred – by tragic irony including a few descending in triumph having survived the Murdewand.

I myself tore a knee cartilage descending the West Flank – which tormented me on and off for 3 years until I finally got it operated on.

Loose rock and shale means there is some stone-fall. With the ‘stepped’ nature of the terrain, much stops before it travels very far. But around some of the buttresses and gullies it doesn’t stop. I was seriously discouraged from taking a short cut down one of the gulley’s when a little fusillade of rocks whistled past my (helmeted) head buzzing like enraged bees. And the impacts they made on the gulley walls 70 feet below me was like a burst of machine gun bullets – with great puffs of sulphurous smelling smoke, a few sparks and a lot of noise.

Another Eiger speciality is verglas. You’d think that the roof tiles and ball-bearings would be enough – but no: the odd stream and melting snow patch by day means quite substantial areas of verglas’d rock in the early morning – and persisting later in some of the shady areas. But spare another thought for any poor sods on the Murdewand, who have this to contend with in their somewhat more vertical environment!

Route finding is difficult on the West Flank. There are odd bits where there are trails to follow, cairns and belay stakes. Nevertheless, particularly on descent, the route is complex, weaves about – and false trails can lead to some rather dangerous places. The very trickiest parts are the lowest rocks between 2700-3000m - and then the upper middle section between about 3300-3600m, where there is a long rising traverse. It would be very difficult navigating safely down in mist – or darkness (both together doesn’t bear thinking about...). I would strongly recommend studying the route very carefully: one advantage of ambling up the lower rocks in the late afternoon is that this potentially confusing part can be studied at leisure, somewhat romantically by the light from the setting sun; and then the next tricky section can be seen clearly for further study from the bivvy ledge.

A last word on route finding: the Route Description below is as detailed as I could make it. It is more detailed than the guidebook I carried on my attempt – yet it barely skims the surface in terms of providing an accurate guide to the route, which is very complex. Also it describes the route under ‘dry’ conditions, with little snow cover. Under snow it would be different (whilst some of the terrain may be made easier, many of the cairns and other route markers may be concealed). A key issue is finding the tops of the sections with belay stakes. For one thing, they provide confirmation of the route. For another thing, being able to hang a rope down some of the steeper sections markedly reduces the risk of a slip. When I was on the mountain in 2008, for additional confirmation of the route, I carried a few thin gardening canes (not really canes – but very thin sticks about 12-18 inches long) to mark tricky bits of the route where cairns and belay stakes weren’t around. The early pioneers used chalk to mark the route. But despite my caution and gardening canes I still made one major blunder which led to an unsolicited 200m round trip – as well as the close encounter with falling rocks described earlier.

Typical Eiger West Flank terrain – showing the downward dipping strata and wetness, which by morning will be verglas.

GETTING THERE

There is excellent access to and around Switzerland by road, rail and air. The road and rail network within the country is comprehensive – and of course, in Switzerland, the trains run on time.

The nearest main centres are Bern (capital) and somewhat nearer, Interlaken. From Interlaken, head south east through the valleys to either Lauterbrunnen or Grindlewald. The famous Jungfraubahn Jungfraujoch railway starts at both of these places – climbing rack and pinion tracks which intersect at the famous pass of Kleine Scheidegg

At Kleine Scheidegg, the skyline is dominated by the holy trinity of Eiger, Monch and Jungfrau – three 4000m giants (well, the Eiger doesn’t quite top 4000m – but it deserves to). This is one of the most photographed views in the world – and for nearly 80 years people have come here to gaze hopefully through thoughtfully placed telescopes to catch a glimpse of the dare-devils (& clinically insane) climbing the North Face of the Eiger.

To access the Eiger West Flank from Kleine Scheidegg there are two choices:

1) To climb the Eiger-Rotstock Via Ferrata via the via Ferrata route. This takes about 2 hours, but is a most enjoyable way to reach the start of the route. If you are a competent enough climber to be setting out on a route like the Eiger West Flank then you could get away without taking a Via Ferrata kit. The Via Ferrata is easy at K3 – and exposure minimal compared to the horrors of peering over the edge, say up at Pt 3668m.

2) To walk or catch the train from Kleine Scheidegg to the Eigergletscher station (near where this famous railway line disappears into the mountainside) – and then follow a vague track zigzagging up the shale covered slabs behind the Rotstock, up to the start of the route. This takes an hour or less, but is a little tedious.

Both these two itineraries converge at the little col between the Rotstock and lower rocks of the Eiger – at around 2600m. This is the start of the West Flank proper.

ROUTE DESCRIPTION – ASCENT

Start at the little col between the Rotstock and lower rocks of the Eiger. Slopes of shale give way to a snow field of variable size, depending on timing in the season. Climb this angling towards the obvious continuation of the snow into a couloir. Don’t be tempted by the little rock gulley passed near to the couloirs entrance – which may show signs of old abseil slings. It is possible to ascend that way, but the terrain soon becomes quite steep and dangerous and it is better to go round the corner into the snowy gulley – from where an obvious exit onto the rocks on the left is soon seen (also maybe some old slings).

Up on the rocks now, the route is reasonably self evident as it angles upwards and slightly to the left up steepish slabs. The occasional piton is passed – which is very useful for the descent. Down-climbing these slabs is possible but hazardous, so it is well worth memorising how to find these pitons from above.

As this ‘first step’ is ascended it can be seen that ahead is apparently barred by a wedge shaped line of cliffs – the ‘thin end’ of the wedge being immediately in front, but the ‘thick end’ several hundred metres to the left and perhaps 100m high, as it borders on the north face.

The route heads approximately upwards and onto the top of the R and ‘thin’ end of the wedge. From here a vague trail follows rubble strewn ledges along the top of the cliffs, heading diagonally up and to the L towards the prominent point at 3060m – where there is the level area of the bivvy site.

From the bivvy site most of the next and middle section of the route is visible. The edge of the west ridge rises up steeply on the left and a few hundred metres away, rising bizarrely out of the north face, is the mushroom shaped rock obelisk of the Kanzeli. One of the north face routes finishes on this feature - and I spotted a couple of climbers reach the top of it when I was settling down for the night in 2008 – see photo in ‘Overview’.

The route now zigzags up on the rocky terrain well to the R of the ridge crest initially, but soon angles towards the Kanzeli – where there is a sobering exposure to quite a substantial bit of north face yawning emptily below. Perhaps with some relief, the route then leaves the edge again – and starts a long complicated rising traverse to the R. A narrow gulley is crossed and presently an area where there would normally be a large snow field (may be very small - or even absent late season?) – which the route passes above.

Still further above, the route appears to be barred by a yet another line of immense cliffs with big spurs dropping down. Two of these spurs are turned, still heading diagonally up and across the face, above the big snow patch. This section is easy to get wrong on the descent. It is worth topping up the odd cairn you encounter – or even making the odd new one, to be sure you get it right coming down. As well as the odd cairn there are occasional pitons or abseil stakes here and there.

After turning the second big buttress the route now heads upwards, angling towards the west ridge again, in the wall of a sort of shallow gulley. You will soon know if you have found the right line, since in due course another and longer series of cemented in abseil stakes and pitons, is encountered. Having by now traversed quite a long way round the west flank the part of the route with the Kanzeli obelisk and the bivvy ledge is no longer visible.

After several hundred feet of very steep scrambling with a few rock steps – still following the trail of belay stakes - the crest of the west ridge is reached again, at 3668m. This is at the top of a small steep buttress, marked at the top by one of the belay stakes – which is bent over and shows faded evidence of its original red paint. At this point the ridge is narrow, but approximately level for a little distance. There is another and even more horrifying view straight down the Murder wall. This is at the top of a particularly vertical section of the face dropping straight down about a mile – in fact the main site popular with base-jumpers. Looking straight across at this point is the top of the infamous ‘white spider’ – feeding into the bottom of which is the ‘traverse of the gods’... a crossing said to be the most exposed on this awful wall and completely unprotected – so perhaps the sort of place you’d appeal to the gods for salvation.

(Perhaps gratefully) leaving the Murder Wall again – note that it will be very important to be able to identify this level area on the crest of the ridge on the return, since with the faded red (bent over) belay stake, it is the key to finding the line of abseil posts heading down and round this particular rock buttress – to (eventually) find the top of the long descending traverse.

From here the route follows the crest, towards another rock buttress, which is a false summit. This buttress is bypassed to the right, away from the crest yet again – following very steep terrain, possibly snowy (would vary) – round the base – and out of sight behind it.

Behind the buttress the route now ascends a snow slope until rejoining the ridge for the final steep snowy crest to the summit.

THE SUMMIT

ROUTE DESCRIPTION – DESCENT

I would re-iterate the importance of having memorised the key areas where the abseil stakes and pitons are to be found – and where the route changes direction. The Eiger generates its own weather and even on a so-called fine day, clouds can come in at the sort of time descent is being made – turning a splendid adventure into an nightmare epic. Add in one of the frequent and infamous Eiger storms and... Let’s not even go there.

From the summit reverse the narrow crest and back down the snow to the back of the buttress, which is turned before crossing the steep mixed terrain to the right - leading to the level bit of ridge crest at point 3668m. Look out for the bent red abseil post.

At the abseil post, descend L and away from the crest, down the back of the rock buttress and onto the series of abseil posts descending the spur near the shallow gulley for about 100m. There is some further descent before starting to look for the start of the traverse.

Make sure you can identify the point at which it is necessary to start angling across to the right – also still descending. Occasional cairns and/or abseil pitons mark the right route. After crossing the two spurs again, the snow patch should be visible below – as well as across the face to the Kanseli (the peculiar rock ‘mushroom’) – and below that, the still quite distant bivvy site. The descending traverse is going to finish at around the Kanseli, but the route across is far from direct. Care and attention is still needed since un-climbable rock steps and bluffs abound.

In 2008 I made too high a crossing and found myself on steep rocks bordering onto a precipitous gulley – up in a corner below the middle rock band. I couldn’t see a sensible way down the rocks, nor anything to belay from for an abseil. I was tempted to put on crampons and down-climb the steep snow-ice of the gulley. But just as I had attached one crampon the earlier mentioned fusillade of rocks came whistling past from the buttress above – and I recognised that the gulley was a natural stone-fall trap. I took my crampon off and made myself back-track about 100m of horrible terrain until I found the route, where it had deviated down a (climbable) rock-step. I’d missed a little cairn.

Once across at the Kanseli it is straight forward for a bit. There is an easy to follow trail which zigzags down towards the bivvy site, but then a few metres short of it angles round to the left along the shaley ledges of the top of the big wedge shaped line of cliffs (as viewed from below – from above there is just yet another crumbling edge with a nasty drop beyond).

This is the last problem area in terms of route finding.

After a descending traverse along the cliff top it is necessary to find the way down to the R to the slabs at the bottom of the West Flank. Turn off too soon and there is the cliff. Turn off too late and there is impossible, precipitous and extremely loose terrain bordering on the snow gulley.

The slabs that need to be found are also steep – but the rock is sound – AND – there is the little sequence of pitons to abseil from.

The slabs end at a little ledge at the edge of the wide snow gulley. It is a straight forward scramble – perhaps assisted by the odd conveniently left sling (there were in 2008) – to drop down on to the snow of the gulley. Note that the snow is quite steep and crampons may be a good idea depending on the state of the snow. It would be a bad end to the day to have a banana-skin moment here – there is some nasty lumpy scree at the foot of the snow slope.

Descend the snow to the little saddle between the Eiger and the Rotstock at 2600m. From here, depending on energy levels, it is possible to turn R and descend the Via Ferrata and thence the grassy slopes descending to Kleine Scheidegg. The shortest descent is straight ahead down the rubble ledges at the back of the Rotstock, heading for the Eigergletscher Station. Depending on time of day, regular trains descend from here to Kleine Scheidegg – from where further trains descend to Grindlewald and Lauterbrunnen.

ACCOMODATION

All types of accommodation - from campsites to self catering chalets to posh hotels – are available in both Grindlewald and Lauterbrunnen.

There is no ‘Alpine Hut’ for the Eiger West Flank (There is a hut for the eastern Mittellegi Ridge and the South Ridge can be accessed from the Monchjoch Hut). Simple dormitory accommodation is available at the Eigergletscher Hotel Eigergletsher Guest House – between the station at 2320m and where the railway enters the Eiger tunnel (eventually emerging at the Junfraujoch). Tel 033 855 2291.

There is simple dormitory accommodation available at the Kleine Scheidegg Bahnhof Buffet at 2060m.

Kleine Scheidegg Bahnhof Buffet Tel 033 828 7828

The Eiger Hilton

In my opinion the way to do this route is to amble up the lower rocks late afternoon and then stay at one of the finest bivvy sites in the Alps. Practically on the edge of a 600m drop there is a level area, to which some kind soul has added a little bit of wooden plank flooring (at least there was in 2008). What this facility may lack in terms of spa baths and room service is more than made up for by the view, especially at sunset. The outlook is of course to the west – and the setting sun turns the giants of Monch and Jungfrau golden then pink – as well as seemingly setting on fire the distant Lake Thunersee (took me a moment to identify what it was blazing down below the clouds late evening in July 2008).

Naturally you won’t get the view if the weather were bad. But if the weather were bad, perhaps it is a bad idea to be up there anyway.

What the Eiger Hilton may lack in terms of spa baths and room service is more than made up for by the view, especially at sunset.

FINAL PICTURES

ESSENTIAL GEAR

It is possible to get all the way up to around 3700m without needing crampons in a ‘dry’ year or late season. But crampons and ice axe would always be necessary for the final snow crest to the summit.

A helmet is a good idea. Several sections are exposed to stone-fall.

Even if climbing solo or as an un-roped party, it is a good idea to carry at least a 30m length of 9mm rope for the descent. It is worth carrying a selection of slings.

For roped parties: harnesses and a small selection of chocks, may provide added security.

Normal alpine clothing including warm layers, gloves, outer gortex layer etc.

Gortex bivvy bag, sleeping bag and other bivvy essentials – if proposing to stay at the Eiger Hilton.

A good camera!

An iPod!!

EXTERNAL LINKS

First Ascent of the Eiger 1858

Jungfraubahn

Kleine Scheidegg

Eiger-Rotstock Via Ferrata

Eiger

Weather