Grand Aletsch Affair

![Zooming in on the Trugberg (3933m)]() rgg image of Trugberg - and behind, the Mönch with lenticular cloud cap

rgg image of Trugberg - and behind, the Mönch with lenticular cloud cap“Hang on Rob!” I shouted at the Dutch member of our team of three “I don’t like the look of that cloud...“

Somehow, from out of a clear sapphire blue sky the Mönch had gained an ominous looking cap. Crampons creaking on the hard rough surface of the glacier I scrambled out of yet another minor crevasse and stopped to look properly.

“Well – you’re the weather expert...“ For some reason Rob, a.k.a. rgg, a.k.a. The Peak Monster deferred to me on matters of weather predicting.

We were at around 2700m, struggling through a wilderness of chaotic and fractured ice – somewhere in the vicinity of Konkordia, a great glacial confluence miles and miles up the Grand Aletsch Glacier, in Switzerland. It had taken all the previous day to get to this point and we had just spent the night out on the ice, our little camp boxed in on all four sides by crevasses. We were now barely 300 metres away from the camp and just climbing out of about the twentieth crevasse of the morning thus far, when I called for the stop.

The Mönch 4099m was actually our first objective - and was also still miles and miles away. Looking at the perfect lenticular cloud cap adorning the summit I could sympathise with those who thought such things were flying saucers. This looked like a UFO: a perfect dome-shape with sharply defined flat bottom. And it enveloped the top few hundred metres of the mountain we wanted to climb. Now that we were looking, a few similar but smaller flying saucers were forming around other tops and also at other random points up in the sky - which was becoming increasingly overcast.

![Camp on Grand Aletsch Glacier]() Camp at 2700m on Grand Aletsch Glacier

Camp at 2700m on Grand Aletsch Glacier “Bloody hell!” I said “This wasn’t supposed to happen...”

The weather was supposed to be good – now. When we had last looked at the forecast, admittedly two days earlier, there had been talk of an anticyclone building and fine weather – at last. It had been rubbish all season as confirmed by Rob, who had been in the Alps most of the summer. But now, after an uncertain looking start two days earlier, it was supposed to be good for several days - and that was why we had come up here; miles and miles up the biggest glacier in the Alps.

“What do you reckon Dad?” asked the third member of the expedition, my 23 year old son Keith.

Contrary to expectation I am not a weather expert. However, in a sporadic alpine career spanning four decades, I have seen a few skies and seen what tended to come after the sort of sky we were seeing just then. Actually, Rob should have known... the last time I had seen such a sky had been with him on the ‘Alps International Expedition 2012’ when the same type of cloud cap had enveloped the summit of Mont Blanc. That had been the notorious ‘donkey’ of Mont Blanc, infamous in the Chamonix valley. Twenty four hours after the first signs the heavens had opened with near monsoon force. One difference though, was that on that occasion a strong weather front had been clearly forecast by the meteorology service days before...

“I think there is a weather front coming” I said “I don’t know why with that forecast or how long it will take to arrive – but I think I wouldn’t want to be up there if did!”

Suddenly those grandiose plans were in the balance. We had been debating how many four thousanders to bag up here... the Mönch next day; Jungfrau the day after – and then the Aletschhorn via a three thousander the Dreieckhorn... With a sky like we were seeing, I didn’t think we would be climbing any of them. Damn!

In common with the weather, the terrain we were on was also throwing up some unexpected surprises. Rob and I had climbed the Gonella route on Mont Blanc the previous year as highlight of the very successful 'Alps International Expedition 2013' . This had also included a long glacier approach. It had been hard work plodding over mound after mound of glacial rubble, but was pretty much just a matter of putting one boot in front of the other until we got to where we were going. There had been a few crevasses to circumvent – nothing too difficult.

This glacier was different. It was about twice as long for a start.

![The mighty Grand Aletsh Glacier]() Down on the mighty Grand Aletsh Glacier

Down on the mighty Grand Aletsh Glacier

![Monch 4099m & Truberg 3933m]() The big glacier and Keith pointing out the mountain he wants to climb

The big glacier and Keith pointing out the mountain he wants to climbThere were the boulder mounds and ice hills again. This time though the whole thing was split every which way with crevasses, breaking the surface up into millions of little islands, like the one we had just camped on. It was almost as if some mad celestial decorator had laid the surface with irregular sized tiles of ice from 10 to 100m across – and then done a really bad job of plastering the cracks in between – such that the cracks varied in depth from a couple of meters to bottomless chasms of indeterminate depth.

I could tell that the Peak Monster was enjoying the challenge of finding a route through this maze. He is a very experienced alpinist and at 54, a year older than me, he still aspired to climb routes of a technical standard that I had left firmly in the past over twenty years before. And even then I didn’t like climbing in and out of crevasses. I always avoided routes with complex glaciers...

Rob was also enjoying instructing Keith on this fractured terrain. I have taken my son on a few easy climbs and via ferrata over the years. He walked up to the top of the 4164m Breithorn at the age of 11. But this was his first proper alpine climbing holiday. As well as being a prolific Alpine and Andean peak-bagger Rob is a natural instructor and had kindly taken the opportunity to coach Keith, starting with a workshop in elementary crampon technique and entry-level peak monsterness the day before.

Keith was also enjoying the maddening obstacle course and was up for front-pointing his way in and out of anything and everything that we happened across – in fact the deeper the better. He had also really set his sights on climbing the Mönch. I had climbed it a few years earlier and before me, my grandfather; Keith’s Great-Grandfather... and Keith liked the idea of being representative of a third generation of the family to make the ascent. I would add though that both the historic family climbs had been from the lofty starting point of the Jungfraujoch – and had not involved the infinitely tougher approach up the Grand Aletsch Glacier. For those who don’t know; the Jungfraujoch is more usually accessed via a famous rack and pinion railway, which starts at from Kleine Scheidegg – and climbs up through a tunnel actually inside the north face of the Eiger.

![RGG Alpine School 1]() Peak Monster school of... Peak Monster school of... | ![RGG Alpine School 2]() ...basic alpine skills... ...basic alpine skills... | ![RGG Alpine School 3]() ...in action on the Grand Aletsh Glacier ...in action on the Grand Aletsh Glacier

|

Rob was thinking of this railway now – and we debated the option of using it as an escape route, if we carried on going. But, the terminus was still a very long way ahead and at 3400m, some 700m higher than our current altitude of 2700m. If we couldn’t climb the Mönch next day we’d end up having expended a phenomenal amount of energy just to reach the Jungfraujoch. At that height the (now) expected weather front would bring snow – and trying to descend the glacier with snow at the top end and rain all the way down from this level didn’t bear thinking about... So we’d end up having to buy tickets for the most expensive bit of railway in the world to get down – and of course we’d end up coming down on completely the wrong side of a very big mountain range. It would involve at least a day of complex and expensive travel to get back to the car...

I was relieved when the other two agreed we’d turn round and go back the way we had come.

It took some time just to regain the ice island we had camped on. By the time we had got back there the sky was almost completely veiled with overcast. In the Grand Master Plan we’d have been returning via the Aletschhorn and Mittelaletsch Bivouac Hut – down a side valley with the Mittel Aletsch Glacier and then to a crossing of the Grand Aletsch Glacier much lower down. Now, we’d have to go all the way back down the very laborious route we had come up the day before...

There was a single, what we had called ‘the motor-way’ section, which was relatively un-crevassed. This went fairly quickly. However, we were soon returned to complex ground again. It was surprisingly hard to find the route. Sections approximating to a regular trail were scanty and difficult to spot. After hours of tortuous progress a single small cairn marked a crucial left turn, to start the move towards the edge of the big glacier – and our exit point. It was still far from straightforward though and we followed a couple of false trails into a labyrinth of massive ice ridges, which terminated in unstable ice-boulder fields or bottomless chasms...

![Small and lost on the Grand Aletsch Glacier]() Looking back up the 'motorway' section towards a distant Rob

Looking back up the 'motorway' section towards a distant Rob![Ice maze leaving Grand Aletsh Glacier]() Keith's image of the Ice maze leaving Grand Aletsch Glacier

Keith's image of the Ice maze leaving Grand Aletsch GlacierAfter more tedious searching we finally found the right hummocky ice ridge to lead us out of the maze. Off the big glacier at last, now there was ‘just a path’ to follow, albeit still rather a long one, to get back to a suitable bivvy for the night - it being way too late to catch the last cable-car back down to the valley.

As we set off up the path the clouds swirling around above us came and went. The sun broke through and it became positively balmy... I began to wonder if I could have made an almighty error of judgement. Maybe this was just a weak front without any precipitation? Nevertheless we could hardly turn around and go back now. But looking right up at the far end of the glacier, to where we had come from, the tops were now completely hidden behind a thick veil of grey cloud...

I should have remembered Mont Blanc in 2012. It had taken a full 24 hours from that first lenticular cloud cap to the start of the rain. Thus far on this trip it had been a matter of only about 6 hours since we had first seen the Mönch summit enveloped in that sinister ‘flying saucer’.

The up side of the slow approach of the weather front was the likelihood of a dry night. Trying to keep the weight down, we had just brought my Mountain Equipment Tundra II tent between the three of us. This was comfortable for two – but a tight squeeze for three – especially with both Keith and Rob being well over 6 feet tall, my middle aged spread – and Rob’s beard. The previous two nights of this little expedition I had slept out in the open, along with much of our gear. If it rained I’d have to join the others in the tent – which would be very uncomfortable with three plus all the gear and beard.

![Panoramic view of the Weissmies, Mischabel, Matterhorn and Weisshorn groups at dusk]() rgg panoramic view of the Weissmies, Mischabel, Matterhorn and Weisshorn groups at dusk on our first evening at our camp at Bettmeralp

rgg panoramic view of the Weissmies, Mischabel, Matterhorn and Weisshorn groups at dusk on our first evening at our camp at Bettmeralp

To Saas Fee

![Our camp site on Bettmeralp]() Our camp site on Bettmeralp

Our camp site on BettmeralpThankfully we had a dry night – back where we had spent our first night, at a little spring on the hillside overlooking the lake at Bettmeralp. We were back down in the valley and re-united with the car by mid-morning. The weather remained threatening looking – but still dry, at least where we were down in the valley. High up on the Mönch could be another matter. We tossed all sorts of ideas around including driving round and through the range – and making another attempt from the other side, via the Jungfraujoch railway – if things cleared – and maybe even bagging the Jungfrau as well, if we took the tent up and set up a camp. But weather conditions remained far from certain. If the weather was bad when they said it would be good and now they were saying it was uncertain, but possibly bad... then a Jungfraujoch trip would on balance most likely end up as a very expensive failure.

We decided to give up on the Bernese Oberland and head south – where it seemed probable the weather would be better, from perusal of Swiss Meteo on Keith’s smart phone. Although I had climbed all of the most accessible summits there and could end up repeating ascents, we decided on the Saas Fee valley as a base. Rob had climbed a couple in the area, including the Lagginhorn – with me in 2012. But there were a number of summits he hadn’t climbed, which would be easy options for getting Keith up some peaks. The Weissmies, Allalinhorn and Alphubel were all other easy four thousanders I had climbed in the past (Alphubel twice). I wasn’t especially keen to repeat any of them for myself – but would happily do so to see Keith get some summits in.

We set up camp at Saas Grund – where I had camped on my solo Alps trip in 2009 – and where Rob had been earlier in his 2014 Alps season back in July... when he had climbed the Jägihorn via the Alpendurst, a UIAA grade V- rock-climb, with Belgian climber Jan, soon after a visit to the Turtmantal and a successful ascent the north face of Brunnegghorn, a respectable alpine ‘Difficile’ they had managed to slip in between weather fronts - and before all the higher summits became almost constantly unattainable, over the rest of the dreadful season to date.

A quick drive up to Saas Fee produced a weather forecast that said basically OK at low to medium levels most of next day – but rain at all levels in late afternoon/evening. But then an excellent forecast (as the front moved on) the following day. After the Aletsch experience could we believe it? Rob had pointed out that conditions had been very hard to predict all over the summer. The usual anticyclone hadn’t been present in the Azores – so the normal weather patterns just hadn’t been occurring – and forecasting of any good weather had mostly been wrong.

We decided on Jägihorn for the next day. Although Rob had already climbed this a few weeks before, he hadn’t done the via ferrata – and this was supposed to be one of the longest and best in Switzerland. Finishing right at the 3206m summit it was the highest. So Rob was happy to give it a try...

Next day was the 5th day of our two week expedition. Surely we’d get Keith a summit on this day... It was mostly overcast, but it wasn’t raining in the Saas Valley – and the top of the Jägihorn was below the clouds. Looking to the north, towards the Oberland, all was hidden behind a wall of heavy grey – so it did appear to have been the right thing to have headed south... we hoped.

Jägihorn via ferrata

![Jägihorn panorama]() rgg image of the Jägihorn 3206m (10,518ft): The Via Ferrata ascends RH subsidiary peak from the lowest rocks before traversing the col to main summit. Rob's climb 'Alpendurst' ascends face of main peak. Descent via LH skyline - and then down scree shoot below

rgg image of the Jägihorn 3206m (10,518ft): The Via Ferrata ascends RH subsidiary peak from the lowest rocks before traversing the col to main summit. Rob's climb 'Alpendurst' ascends face of main peak. Descent via LH skyline - and then down scree shoot belowWe grabbed a lift on the Gondola from Saas Grund up to Hohsaas at 3100m. It was an easy hour and a half’s walk from here to the start of the via ferrata: first descending to near the Weissmies Hut and then scrambling up a crest of moraine. Once again, it looked as if the weather was not going to be on our side... Our objective was soon enveloped in dark cloud. Oh well – at least it wasn’t raining...

About 100 metres up the via it started to rain. It wasn’t heavy rain. But quickly all the rocks became saturated and very slick. With by far the greater and most exposed part of the route still up ahead – and a steep unprotected descent from the summit – Rob was the first to be counselling caution, this time.

“I think we want to be thinking about turning back” he said, water dripping from his beard and down into the steep crevice we had just climbed.

![Jagihorn via ferrata]() Close to the bottom - route ascends buttress behind Keith Close to the bottom - route ascends buttress behind Keith | ![Jagihorn via ferrata]() Rob with water dripping out of his beard... Rob with water dripping out of his beard... | ![Jagihorn via ferrata]() Keith at high point, about to turn back... Keith at high point, about to turn back... |

We slithered our way awkwardly back down all the cables – and back to the boulder field at the bottom. Less than an hour later we were steaming gently over steaming mugs of cappuccino in the Weissmies Hut at 2726m. Damn it. We were nearly half way through this trip – and we still hadn’t climbed a single summit – and it was by no means certain we would do so in the immediate future. After the Alestch experience I struggled to believe the optimistic Saas Fee forecast for the next few days. At this stage of the 2013 trip Rob and I had already bagged 3 summits and were setting about taking in a few more with ‘Traverse of the tops’ on Monte Rosa. Even in 2012, when weather was mostly fairly poor, we had still got up Aiguille du Tour by this stage. In my solo 2009 trip, I had climbed 3 summits... I tried to put a positive slant on things by telling Keith that, as an apprentice alpinist, it was important to learn the gentle art of retreat – before progressing on to the summits...

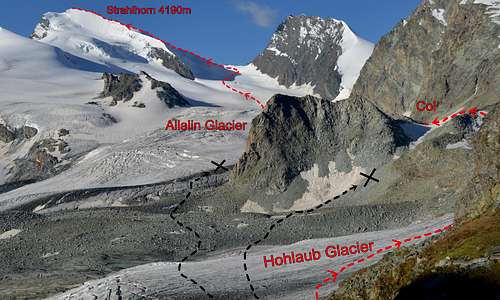

Just in case the forecast was correct we had made a plan for the next three days. Somehow, during the night, this infernal rain was supposed to stop. Assuming it did then battle plan called for a UIAA Grade V (TD+) Alpine Start well before dawn: we’d have to strike camp, sodden tents and all; get packed up – and then drive up to the big car-park at Saas Fee... and then catch the first cable-car of the day, up to funicular railway tunnelling its way up from Felskin up to Mittel Allalin at around 3500m. We then proposed to climb the Allalinhorn 4027m, following same easy (F+) route I had taken on my solo ascent in 2009. But this time, instead of returning to the metro station, we hoped to descend the harder route of the Hohlaubgrat (PD+), on the opposite side of the mountain – and thence down the Hohlaub Glacier to the Britannia Hut, at 3030m some 500m below our start. From there we hoped to climb the Strahlhorn, one of the fairly big 4000ers at 4190m. This was a mountain I hadn’t climbed before and had been vaguely on my wish list.

After a second cappuccino we could put the moment off no longer. Re-acquainting ourselves with our wet water-proofs and boots, we left the warm comfortable Weissmies Hut (much nicer than the one up at Hohsaas...). A descent of 300m took us down to Kreuzboden, the half-way station of the gondola we had ascended earlier.

That night we had a slap-up meal at Saas Almagell. Comfortably bloated, we were disconcerted to note that it was still raining when we emerged from the restaurant – and it was harder than ever to believe that this was going to stop by morning...

Allalinhorn 4023m - traverse

At 4.30 am anticipating Rob’s alarm, I stuck my head out of the tent – expecting to very quickly pull it back in again... bloody hell – STARS! Water dripped off the tent door and down my neck as I strained to turn my head to look upwards... But yes – a myriad of twinkly dots of light sparkled in the heavens high overhead. I had not expected this and struggled to shake out the fog pervading my head – and get into climb mode. We were now faced with a supreme challenge: to get up and pack up two disordered and sodden tents – and kit for 3 days up in the mountains – and catch the first lift up from Saas Fee; a special ‘climbers departure’ – scheduled before the normal departures became mobbed by skiers a little later. All this, in complete darkness, by headtorch light...

One of the biggest parts of this challenge would be getting the Peak Monster moving in time to make the deadline of this crucial first lift. A veteran of many hundreds of Alpine and Andean ascents, Rob by his own admission, struggles with Alpine Starts – and the whole shebang is complicated by his monster breakfast needs. He has to eat a lot to propel his lean frame up any mountain he climbs – and the process is not quick.

Keith and I were all for just bundling everything in the car and getting up to the big underground car-park at Saas Fee – where there would be some light to get ourselves organised by. With the rain as well as darkness we had decided not to even try to get organised the night before, bumping into each other in the confined space of the two man tent. But Rob, anticipating his early morning sloth and with a little more space in his own tent, had indicated he would get himself sorted – such that he should have little to do in the morning other than pack his tent and have breakfast...

The day groaned off to a grumpy start to the paradoxically jaunty tones of Rob’s alarm (which instantly threw me back in time to 2013 and the Gonella Hut... ). As per battle plan Keith and I bundled everything into the disordered chaos of the car interior, hoping our torch beams hadn’t missed anything dropped into the sodden grass at our feet. Muffled grunts and other sounds were emerging from the Peak Monster Palace... seemingly he had decided he was doing his packing in the morning...

Chaotically and with some difficulty we managed to entice the sleepy Dutchman out into the darkness. His possessions including his sodden tent were crammed into a by now protesting car. The only problem, was that there was now no room for him... In daylight and in the dry, we found everything including the three of us, just fit. In the grumpy, dripping wet pre-dawn darkness – there seemed to be no chance. In the event, we did somehow manage... The Peak Monster, master of the Grade V, is accommodatingly bendy – and Keith and I, working from the outside, got most of him in by filling scanty pockets of space along the back seat with him. His beard was more problematic – and required use of an old New Zealand sheep-farming technique to get it corralled.

![Allalinhorn 4027m from metro alpin]() Allalinhorn 4027m from metro alpin

Allalinhorn 4027m from metro alpin![Approach to Allalinhorn 4027m WNW ridge]() Approach to Allalinhorn WNW ridge

Approach to Allalinhorn WNW ridgeAn indeterminate amount of time later we found ourselves up at the car park – and with some relief, I pulled into a space, situated close to one of the lights illuminating the wide expanse of the interior. Presently a mix of wet and dry equipment was strewn everywhere. At last we could properly see what we were doing...

Keith and I packed, whilst the barbarian Dutchman slowly consumed an entire packet of breakfast cereal, tipped into the biggest bowl I have ever seen. Periodically I darted anxious glances at my watch. On the face of it, we were in reasonable time for catching the special gondola departure. However, from my experiences in 2009, I wasn’t sure how far we had to walk to get to the particular terminus this left from. There were at least two widely spaced and interconnecting possibilities in the Saas valley. In a rush to catch the last departure of the day five years earlier, having just climbed the Mittaghorn, I remembered going to the wrong one and then having to run with full backpack about a kilometre to the furthest away option, where a kindly attendant allowed me to get on despite being late...

As it turned out, the special departure was from the nearest terminus – and we didn’t have to walk the extra kilometre I had been anticipating. We were in plenty of time...

About an hour later we were stunned to emerge from a dark tunnel into the golden sunlight at close to 3500 meters, soon after dawn. An array of four thousand metre peaks was alpen-glowing in the sky before us – including the familiar rounded shape of the Allalinhorn dead ahead. Any residual grumpy confusion from the early morning evaporated.

![Fletschhorn, Lagginhorn and Weissmies towering over Mittaghorn and Egginer, towering over Mittel Allalin]() rgg image: looking back over Mittel Allalin towards Lagginhorn and Weissmies

rgg image: looking back over Mittel Allalin towards Lagginhorn and Weissmies“Two hours and we’ll be up” declared a happy Peak Monster, back in his element again. I felt an added warm feeling: Keith was going to get a summit...

The pressure was off now. There was ample time to climb the Allalinhorn, negotiate the unknown of the Hohlaubgrat and get all the way down to the Britannia Hut. Looking up at our objective, much of the easy way up was out of sight round the back of the mountain. The Hohlaubgrat (east-north-east ridge) was visible in profile descending to the left of the summit. The crux was a prominent rock step, not far along from the highest point... and the guidebook suggested there were belay posts in place...

As we took in the scene and had a drink and snack (in Rob’s case, a second breakfast) the first of the days skiers were arriving from the depths below – and scattering themselves off into the snowy vista. The first part of our route involved ascending piste – with the attendant objective danger of being run over, by a hurtling and excited 14 year old...

A half hours vigilant walking got us off the piste and onto the main alpinists trail, winding up and around the back of our mountain. We stopped to apply crampons and sunblock. Although five years earlier I had been happy to solo this route, I was aware that the glacier had deteriorated since then – and I suggested we rope up. We then left the sunlight behind and climbed into shaded slopes of steepening snow on the western flank of the Allalinhorn. There were a couple of largish crevasses to cross, but other than that, the route was much as I remembered it. Rob was up at point and set a moderate pace. At the back, I could keep up – but was aware that I wasn’t as fit as the last time we had climbed a mountain together. Keith, on the middle of the rope, was having no difficulty despite having done very little fitness training before this trip... the joys of being 23 years of age!

About an hour later, we climbed back into the sun at the Feejoch, up at 3826m. Abruptly a new vista of summits came into view, on the Zermatt side of the mountain. There before us was the striking shape of the Matterhorn, which I had climbed 34 years before. And to its left I was pleased to point out to Keith the triple summited bulk of the Breithorn – his first and only four thousander from twelve years before. To the left of that were the comely shapes of Castor and Pollux – two four thousanders on my wish list, but climbed by Rob in 2012... and even further to the left and much nearer, were the twin bulks of the Rimpfischhorn – and the Strahlhorn, our objective for the next day.

![Strahlhorn 4190m]() Strahlhorn 4190m

Strahlhorn 4190m![The 'Twins' and Breithorn from Allalinhorn 4027m]() The 'Twins' Castor & Pollux plus Breithorn from Feejoch

The 'Twins' Castor & Pollux plus Breithorn from FeejochJust as I had done at the same time of the year five years before, we now climbed straight up into the rising sun, on gently rising slopes of snow. The summit was also in sight up ahead, at the top of a dark triangle of loose rock. The easy trail meandered round to the right of this rock and then left again along a crest to a clearly visible cross, marking the highest point. In 2009 there had been a lot less snow and I remembered a little rocky scramble in this section. This year, much less of the summit rock was exposed and it was a simple matter to walk round it to access the final crest.

I had by now shared 18 alpine summit Berg-Heil’s with the Peak Monster on the two previous ‘International’ Expeditions. Now I really looked forward to sharing such a moment with my son. It had long been a dream of mine to share an alpine summit with at least one of my three children. I had taken them all on easy rock-climbs, some vie ferrate and up a few mountains in the UK, but never to an alpine summit. Back in 2001 I had tried, on a family holiday. Indeed an eleven year old Keith had successfully walked to the top of the Breithorn – but with my wife, whilst I had to take his younger siblings back down. At the tender ages of nine and six the thin air of close to 4000 metres proved too much – and I turned round with them about 200 metres below the summit. So, it was an emotional moment for me when we arrived at the little summit. We all three exchanged Berg Heil’s and hand-shakes – but I felt compelled to clasp Keith in an ungainly bear-hug, which in the limited space nearly took in a handful of Peak Monster beard as well...

![Climbing Allalinhorn 4027m upper WNW ridge]() Climbing Allalinhorn 4027m upper WNW ridge Climbing Allalinhorn 4027m upper WNW ridge | ![Easy final slopes to Allalinhorn 4027m summit]() Easy final slopes to Allalinhorn 4027m summit Easy final slopes to Allalinhorn 4027m summit | ![Approaching Allalinhorn summit 4027m]() Approaching Allalinhorn summit 4027m Approaching Allalinhorn summit 4027m |

With such limited space and the ritual photography completed, we soon moved out of the way to let a newly arrived party have their turn on the top. We walked back along the nearly level summit crest to find a place to sit down and enjoy snatches of view – glimpsed between wisps of light cloud. The clearest direction was to the north, with an apparent eagles-eye view straight down 500 metres onto the Metro-Alpin terminus, from which we had emerged a little over two hours before. Beyond and some 2100 metres below, the roof tops and meadows of Saas Fee now shone in the sun. Towering over everything, including our summit, were the mighty giants of the Täschhorn and Dom – the traverse of which was the hardest and finest route I did in the Alps way back in 1986. Across the Saas valley and in the middle distance, there were the more recent old friends; the Weissmies, which I had soloed in 2009, and Lagginhorn, which I had climbed with Rob in 2012. It was even possible to get occasional glimpses of the far off Bernese Oberland, although there was more cloud build up over there.

![Allalinhorn Summit]() Alps International Expedition 2014 - summit portrait

Alps International Expedition 2014 - summit portraitThe Hohlaubgrat

What goes up generally must come down – and we turned our attention to our descent. The route we had just ascended, like the even easier and shorter ‘normal’ route on the Breithorn (from the Kleine Matterhorn cable car station) did feel a little bit like cheating – so were about to justify ourselves by descending the Hohlaubgrat, or ENE ridge of the Allalinhorn, all the way down to the Britannia Hut. At around 1000m this was double the height difference of the ascent from Metro-Alpin – and at PD+ it was a technically harder climb. We walked further along to the end of the 100 metre long horizontal summit crest. A short rocky scramble dropped us down onto the Hohlaubgrat proper. After the gentle slopes of the morning, this was now serious alpine terrain. It was much steeper for a start. To our right was probably a cornice – overhanging a sheer drop of over 1000 metres. To our left, the snow slope wasn’t sheer, but it soon dropped off very steeply – down to the pistes around the Metro-Alpin.

![High on the Hohlaub ridge, above the crux]() rgg image: High on the Hohlaub ridge, above the rock-step

rgg image: High on the Hohlaub ridge, above the rock-stepKeith had in the past had a little bit of instruction from me on crampon and ice-axe technique – and more recently a comprehensive refresher courtesy of our Dutch companion. However, this was by far the most serious place he had been and coming down last, I watched his technique a little nervously...

“Don’t forget axe in the upper hand Keith” I found myself reminding him “And watch those crampons...”

But he was coping fine. He clearly remembered the lessons – and didn’t seem fazed by the significant exposure. I felt proud of my son.

I now turned my attention to the next and most difficult section of the route. About 30 metres ahead the crest terminated at an obvious rocky edge. This was the top of the crux: a rock step, said to be some 50 metres high. I was anxious to get down to it and check it out properly – more concerned than usual, with the added responsibility of Keith’s safety and well-being.

When we were about 20 metres from the edge I could see what looked like a bolt placement there, obviously to provide a belay. The guidebook mentioned belay stakes – but maybe there were some of those as well, but out of sight. What I could see though was reassuring. Now... would we be abseiling – or would we down climb using any belay points as runners? I could still see nothing of what was below though...

Just at that moment a head popped up into view, level with the bolt. We stopped – still about 20 metres from the edge. The head then spoke to us. He said he was in the first of three parties coming up the step and asked if we’d mind waiting – out of the way...

![Top of rock step Hohlaubgrat, Allalinhorn 4027m]() The 'head' appearing at the top of the rock-step

The 'head' appearing at the top of the rock-step This was going to be tedious... the ‘Hillary Step’ at the top of the summit crest of Everest came to mind. That was another and rather more famous bottle neck – where the delays caused by waiting to get up or down have literally resulted in deaths - when climbers have ended up delayed too late to be able to get down safely. Fortunately our little ‘Hillary Step’ was at 4000 as opposed to 8800 metres. So the consequences of a hold up shouldn’t be quite so dramatic... but it was potentially annoying.

It was still frustrating not being able to see. I wanted to get right down to the edge and have a good look for myself – not just accept the word of a complete stranger that it wasn’t possible to pass. Maybe we could bypass the obstruction with an abseil? What if with the delay caused by slow parties moving one at a time, even more parties arrived?

The expedition Dutchman was thinking differently. Abruptly he started digging an excavation in the snow... and for a moment I wondered what on earth he was doing... did he think we were back on the top of Mont Blanc, as in July 2013, when we had dug a snow cave and spent a rather uncomfortably wild night? Impatient to eye-ball that rock step, I asked him somewhat testily what he was doing. Absorbed in his task, he ignored me. I asked again just as realisation dawned. Not that I really thought he was trying to dig a snowcave... but it was very tempting to suggest so in rather sarcastic tones...

Rob had resigned himself – as well me and Keith – to the long wait. A great scientist as well as peak monster, he was engrossed with some applied engineering in the setting up a Dutch Alpine Club approved snow anchor. His priority was to prevent any members of the party from joining the skiers on the pistes 500 metres below, which was not unreasonable. But it would also prevent me from eye-balling the rock step. Mildly exasperated I gave up and allowed myself to be resigned – given the precariousness of our particular situation it wasn’t worth an argument - but I would have preferred to have dug in closer to the step.

Keith however, wasn’t going to let it go – and had perhaps become a little irritable, breathing air of a thinness he hadn’t experienced for over 12 years. He thought Rob should reply to my enquiry – and said so rather forcefully – and all of a sudden World War III broke out... and I had to remind the team that clinging to a steep snow slope wasn’t the best place...

We ended up waiting close to an hour. I contained my frustration at not being able to see and periodically shifted uncomfortably from one foot to the other. A forty five degree snow-slope is not really conducive to relaxation, especially if you have a spine like mine. I tried to distract myself by looking at the view – but that was mostly lost behind the clouds still swirling around the summit.

Finally – and seemingly with some difficulty – the last party climbed awkwardly into view. The leader smiled apologetically, before they slogged laboriously up past us, panting in the thin air. Bloody hell – at last! Rob freed rope for me and then Keith to move down and I moved off straight away – keen to get to grips with the obstacle, before any other parties appeared. Slightly stiff from the uncomfortable wait I nevertheless cramponed quickly but carefully towards the mysterious edge, wondering from the slowness of the three parties, what kind of horrors lurked below...

The Hillary Step, as by then I was calling it, was not too bad once I got to where I could see things properly. Just below the edge and the bolt, was a short wall. At the bottom of that a shallow ledge sloped diagonally across to where the route obviously went straight down very steep mixed ground of mostly snow, but with a couple of little rock steps. The section was generously supplied with belays in that there was a second bolt a little way along the ledge – and then at least two belay stakes that I could see, one just beyond the far end of the ledge and another about half way down the steep mixed ground.

![Keith descending the rock step high on the Hohlaub ridge as more climbers approach the base of the rock step]() rgg view of Keith & me descending the crux - guide + client below

rgg view of Keith & me descending the crux - guide + client belowAt the bottom of the mixed ground the route disappeared out of sight between two rocky outcrops. It clearly became even steeper at that point – but then looked no distance at all to where a line of boot-prints emerged at the continuation of the snow ridge, right at the bottom of the step.

“It’s not too bad” I called up to an alert Peak Monster “there are a couple of belay stakes that I can see and we can probably down-climb it easily enough. Might also be short enough to abseil – see what you think!”

I clipped myself to the bolt and then shortly afterwards did the same for Keith, who soon scrambled down the little wall. We then moved as far sideways as we could to make way for Rob, who was by then dismantling his snow belay. I took in rope as he joined us.

![High on the Hohlaub ridge]() rgg view: Keith still just visible at the steepest part

rgg view: Keith still just visible at the steepest partWe briefly debated how to proceed, but I deferred to Rob, who is much more up to date with technical climbing then I am. He agreed an abseil may be feasible – but with the unseen bit down at the bottom he was not sure whether the doubled rope would reach all the way.

In the event a sort of compromise was reached. Rob would belay both me and Keith at the same time, the two of us moving together with the short rope which was already between us. With not much less than 50 metres of available rope we would easily reach the bottom. I had offered to place runners at each of the belay posts to protect Rob if he wanted to down-climb. But he pointed out that it would actually be easier for him to abseil – breaking his descent in two if necessary. A shortish diagonal abseil would reach the first belay post. We thought that the doubled rope would probably reach the bottom from there. If not, we would be able to let him know - and then he could simply hop to the next post below and abseil from that.

Keith was quiet as Rob and I quickly re-organised the rope and sorted out a minor tangle at the belay. Our position was somewhat exposed – and not surprisingly he was a little nervous at the thought of what was to come, which was well outside his previous experience. When Rob was ready I set off with Keith following just behind. The climbing required concentration and occasionally involved an awkward move over one or other of the exposed rock outcrops, but we made steady progress. I was pleased to note that Keith was moving confidently and safely.

Low down the unseen bit turned out to be a wall of rock about 6 metres high and split by a part snow-filled crack. Still moving simultaneously Keith and I quickly scrambled down this final obstacle – alarming a Swiss Guide who had just arrived with his client and tied on at the bottom. The guide didn’t realise we were being belayed from above and thought we being overly casual moving together on a short rope on such exposed terrain – and he suddenly lunged across and grabbed my rope. Before I could stop him, he had clipped me to the bolt to which he and his client were attached. He started gesturing that I should be belaying Keith, all the while jabbering at me in excited German - until he realised I couldn’t understand – and then changed to heavily accented English.

By then Keith was down – and the guide started lunging across at him, trying to grab his rope in his desperation to save us both from the void below. Although now at the bottom of the rock step, the terrain was still far from flat and plunged impressively and giddyingly down towards Metro-Alpin.

At last – and with the help of his client – the anxious guide was made to understand that we were being belayed from above, by an unseen third person. He apologised and embarrassed now, backed off out of our way. I un-clipped the rope again, before re-attaching myself and Keith to the bolt, using slings. We needed to free the rope for Rob to use for his abseil.

Oblivious of the goings on with the Swiss Guide, Rob was meanwhile shouting down to ask if we were at the bottom. I replied that we were – and in due course the freed rope twitched a couple of times, before jerkily moving up and out of sight above the wall.

The Swiss Guide, with no-body needing to be saved, turned his attention back to his client and got her organised to belay him up the rock step. As he started climbing, I warned him to watch out for our rope dropping down from above. He fixed a runner just before climbing up out of sight – at which point the Peak Monster appeared outlined against the sky, flicking the rope to get it over the top of the wall.

“You can take some pictures” he said, by way of a greeting. And I did...

![Abseiling the crux of the Hohlaubgrat, Allalinhorn 4027m]() Rob abseiling down the rock-step Rob abseiling down the rock-step | ![Rock-step on the Hohlaubgrat, Allalinhorn 4027m]() Below the rock-step Below the rock-step | ![Top of the Hohlaubgrat, Allalinhorn 4027m]() Top of the Hohlaubgrat with rock-step Top of the Hohlaubgrat with rock-step |

In due course the International Expedition of Dutchman and two Anglo-Kiwi’s was re-grouped at the bottom of the Hillary Step. Her leader secure somewhere up above, the client climbed up out of sight to join him. We turned our attention to the next section. The Hohlaubgrat from this point looked to be entirely on snow – and followed an undulating course for some considerable distance. For the initial few metres it was steep enough to down-climb face to slope. But the angle soon eased to the point that up-right walking was reasonable, with a bit of care.

A look down and across to Metro-Alpin confirmed we were still very high and with a lot of height still to lose. By the time we got down to level with this prominent landmark we would only be half way down in terms of reaching the Britannia Hut.

About 400 metres below the Hillary Step, we followed the trail away from the crest of the ridge and in the general direction of the Metro-Alpin. This was now level with us and at the top of the crags of the Hinter Allalingrat – which dropped down to the Hohlaub Glacier – which we would be reaching after another couple of hundred metres descent. Once we reached the glacier, the most interesting part of our journey was behind us. The Hohlaubgrat had been a fine ridge route. Now all there remained was a weary undulating glacier descent, to lose the remaining 500 metres of height - but with a sting in the tail. The final section to the hut involved an unwelcome 80 metres of height gain.

![Hohlaubgrat, below rock-step, Allalinhorn 4027m]() Lower Hohlaubgrat, below rock-step

Lower Hohlaubgrat, below rock-step![Hohlaub Glacier]() Hohlaub Glacier

Hohlaub GlacierThe Hohlaub Glacier required a degree of concentration. There was significant crevasse danger – and we moved cautiously, back to longer intervals on the rope and with the ‘glacier knots’ tied again.

We reached the Britannia Hut at around 3.30pm – about five hours after leaving the summit and approaching eight hours after setting out from Metro-Alpin terminus. This had been a short day compared to the days Rob and I had withstood on Monte Rosa and Mont Blanc, in 2013. Nonetheless I felt very weary and recognised not for the first time that I wasn’t anywhere near as fit as I had been the previous year. I also hurt in various places – especially my long suffering back. But on a positive note some Achilles tendon trouble, which had been annoying on the Aletsch Glacier, actually wasn’t painful anymore. With the continued abuse, it was almost as if it had finally just given up.

At the hut, the Strahlhorn 4190m dominated the skyline, even though the Rimpfischhorn 4199m beside it was all of 9 metres higher. Looking at it my feelings were mixed. On the one hand I felt a certain amount of excitement at the prospect of climbing a mountain I hadn’t climbed before (and a 4000er at that). But on the other hand I was daunted by the amount of effort involved to get up it. Unlike the Allalinhorn this would be an arduous ascent, up a complex glacier – and Goedeke estimated ‘6-7 hours’ for the ascent in his Alpine 400m Peaks guidebook.

For the Allalinhorn we had climbed 500 metres and descended 1000 – and I was tired. With the Strahlhorn the height difference between the summit and the hut at was 1160 metres. But due to complexities in the early part of the route there was an extra 3-400 metres to add on = a total of around 1500 metres ascent. This still wasn’t as much as the 1800 metres ascent Rob and I had climbed to reach the summit of Mont Blanc via the Gonella Route, the previous year. But it was more than enough for me in my current state of fitness.

![Allalinhorn 4027m and Hohlaubgrat]() Down on the Hohlaub Glacier looking back at Allalinhorn 4027m and Hohlaubgrat

Down on the Hohlaub Glacier looking back at Allalinhorn 4027m and HohlaubgratStrahlhorn 4190m

![Lower Houlaub Glacier and route to Britannia Hut]() Lower Houlaub Glacier and unwelcome 80m ascent to Britannia Hut Lower Houlaub Glacier and unwelcome 80m ascent to Britannia Hut | ![Britania Hut 3030m]() Britannia Hut 3030m Britannia Hut 3030m |

Normally I’m not bad at alpine starts and I can usually rely on myself to wake up before any alarm – and the anticipation of an alpine dawn brings me to full wakefulness very quickly. This time, I was in a deep sleep when the melodious tones of Rob’s alarm cut through the darkness of the hut dormitory. It took some effort to get up and moving. I couldn’t shake off the fog of persistent fatigue and thought I was probably still feeling the effects of the hard days on the Grand Aletsch Glacier, in addition to those of the modest exertion of the previous day. Keith on the other hand seemed bright and alert. Even Rob was soon moving purposely this time – compared to the grumpy confusion of the Allalinhorn start, the day before.

We dealt with the business of breakfast, even full Peak Monster breakfast, got packed and departed the hut in the pre-dawn darkness of around 5.30 am. Although there was supposed to be a nearly full moon, it seemed inordinately dark. In my jaded state the mere business of finding our way by torchlight, down to the glacier 80 metres below, seemed impossibly complex. But we got there. We put on crampons and the rope. All I wanted to do then was just plod, without having to think. I wanted to let someone else make the decisions and to manage the complex issues of route finding...

The damn Dutchman expected me to find the route.

![Strahlhorn 4190m normal route topo]() Strahlhorn 4190m normal route topo - daylight view!

Strahlhorn 4190m normal route topo - daylight view!The previous evening I had made some enquiries in the hut and even walked outside to try and see where the route went. But I couldn’t see key parts of where the route went from the hut – and didn’t have the energy to walk all the way back down the trail to the glacier to where I might have been able to fully piece it together. However, having at least tried, this officially qualified me as route expert.

I looked hopefully around for a Belgian couple who we knew were climbing the Strahlhorn that day. They had been somewhere near in the blackness at the edge of the glacier – and maybe they knew the way. But in the time taken to put on crampons the pin-points of light from their head-torches had unaccountably vanished. Other torches were in view – but seemed to be heading in a different direction to the Strahlhorn. Bugger!

Crampons grating I walked a few steps out on to the Hohlaub Glacier. There was no trail whatsoever on the hard abrasive black surface of the ice. We hadn't seen one the day before, in the light - so I am not quite sure what I was expecting in the inky darkness of pre-dawn.

Irritated at the effort involved, I tried to penetrate the fog obscuring my memory as well as the blackness ahead. One thing I did know was that to reach the Strahlhorn we needed to be on a different glacier to the one we were standing on, the Hohlaub Glacier. We needed to get across the Hohlaub, to reach the much bigger Allalin Glacier at a point a couple of kilometres away. Another thing I knew was that the direct route straight across the ice at our feet then involved crossing a large boulder field before joining the bigger glacier at one of the worst of its infamous crevasse fields. This I had seen in daylight. It didn’t bear even thinking about trying to cross it in darkness.

Just to the right of the boulder field was a spur coming off the continuation of the Hohlaubgrat, of the Allalinhorn – which we had descended the previous day. This spur was the key to connecting the two glaciers. The problem was exactly where to access it.

The spur was a little complex. Actually it was two spurs one after another, the second or southerly of which ended in a little tiny peak. What I didn’t know was whether we should go across the edge of the boulder field and then climb up between the first (northerly) and the second (southerly) spur – to reach a little col just to the west of the peak... or should we take a less direct route, diagonally (south-west) across the Hohlaub Glacier - to then climb over the first spur – and thence across to the little col.

From the little col, it should be a simple matter of a short descent to the Allalin Glacier – from where (theoretically) all route finding difficulties were over.

The problem with the indirect route to the two spurs was that it involved a much bigger chunk of Hohlaub Glacier – and somewhere in that chunk was a crevasse field. So the choice was between boulders or crevasses... But the final piece in the jigsaw was that in daylight, high up on the snow at the top of the first spur, I had seen possible evidence of a track. Neither Rob nor Keith questioned my decision to take the indirect route – with the crevasses. Any questioning would have come later, after we got lost...

I started to put one foot in front of the other – and we cast off into the blackness. Our entire world was the little bubbles of dim torchlight we inhabited. I picked a plausible direction. Again, nobody complained, so I kept on going. I reversed what I thought was the last part of our route on the glacier the day before – and at some point I started angling away to the left, out towards the middle of the ice where as yet unseen in the darkness I was ready to find the route barred by an impossible crevasse at any moment.

![Minutes before sunrise in the Alps]() rgg image: the skyline as it caught fire...

rgg image: the skyline as it caught fire...![Keith at dawn]() rgg image: Pre-dawn light top of first spur - Hut behind V notch in dark ridge

rgg image: Pre-dawn light top of first spur - Hut behind V notch in dark ridgeIndeed, there were a few crevasses, but they weren’t big ones – and we were able to jump over most of them. To my surprised relief we were able to keep going approximately where I wanted to, with only minor deviations. After half an hour or so, the slightly lesser blackness of the snowy spur was appreciably closer. Another half an hour and we were cramponing slowly up it, with no more obstacles between us and the top. For the first time that day I felt something approaching pleasure. And the dawn was now not far off. A bit of alpenglow would surely infuse me with a bit more energy. By the time we had climbed about seventy metres to the top of the spur grey light was beginning to illuminate things round and about. It was a little cloudy – and that explained why it had been so dark earlier. But the cloud cover wasn’t total – and as we picked our way towards the little col some 300 metres distant, the horizon to our left started to catch fire...

The terrain we were working our way across was a mix of rocks and snow patches. We had all kept our crampons on, although this was tedious on the rocks. Keith had untied himself from his position at the middle of the rope. Perhaps unwisely Rob and I had stayed roped - out of expediency rather than need. We had thought we’d be reaching the big glacier (with attendant need to be roped up again) quickly...

We didn’t reach the glacier quickly. With hindsight we should have taken off our crampons and the rope. When we finally reached the col we found a steep boulder field dropping down to the glacier, which turned out to be annoyingly far below (70 metres as it happened), not least since any height we lost now, we’d have to gain again on the way back. The only consolation was that with the still increasing light of dawn, we could now see. Crampon footed we continued to grate our way downwards through and over the obstacle course. And Rob and I continued to put up with added complexity of managing the rope and trying to prevent it from snagging on hundreds of rocky projections all around.

The Strahlhorn was now in full view. At around 7 am the top began to glow as the first sunlight caught it. We were nearly at the glacier, but stopped to admire the spectacle. Over a few moments the colours went from rosy to onwards through an entire spectrum of golden – and the illuminated area moved further down the mountain, until it eventually started to catch the far distant upper reaches of the huge glacier we were about to ascend.

![Keith watching the early morning sun on Strahlhorn from the edge of the Allalin Glacier]() rgg image: Keith watching the early morning sun on Strahlhorn from the edge of the Allalin Glacier - where I tripped over is amongst rocks just a little further on

rgg image: Keith watching the early morning sun on Strahlhorn from the edge of the Allalin Glacier - where I tripped over is amongst rocks just a little further on

Having successfully negotiated the steep boulder field in our roped and crampon footed state I let my guard down, down at the edge of the glacier. Due to a combination of residual tiredness and the distraction provided by the after effects of the dawn, I lost concentration... and tripped over the rope...

I plunged headlong, forwards as much as downwards. Somehow there was time to acknowledge that there was no question of being able to recover my balance. But there wasn’t time apparently to get an arm up to break my fall (which would in any case have probably just resulted in a broken wrist).

So, it was my chest which took the full impact, right onto a hard rocky prominence – and the impact knocked the breath out of me.

Strangely it didn’t hurt that much initially. But I lay face down for a moment, winded. Then I rolled over onto my back to see the surprised faces of Rob and Keith looking down at me. There was now a fiery feeling at the point of impact just to the right of my lower sternum.

“Are you alright Dad?” from Keith.

“Not sure...” I wheezed, still winded “...just wait a moment while I work out whether I’ve broken a rib”

After several moments, I managed to move into a sitting position – hunched and hugging the now blazing area at the front of my chest. I came to the conclusion I hadn’t broken anything... at the point of impact I knew that the ribs were composed of relatively springy cartilage – the more breakable bony sections being further round. Presently, I got to my feet. A little experimentation confirmed I could walk – and that although my chest hurt fiercely now, normal breathing didn’t seem to make that much difference – and neither did the pull of my fairly light rucksack.

![Early morning on the Allalin Glacier]() rgg image: Lower Allalin Glacier - Rob's view looking forwards... rgg image: Lower Allalin Glacier - Rob's view looking forwards... | ![On the Allalin Glacier looking back]() ... and my view looking back at Rob taking previous picture ... and my view looking back at Rob taking previous picture |

We set off again. In anticipation of being the slowest member of the party I went at front. I would have been slow anyway, with the residual tiredness I still hadn’t been able to shake off from the early morning. But with the added demands from moderately strenuous walking my breathing did become more painful – and this meant my chest injury now added further limitation... In the mean time, Keith had tied back on to the middle of the rope again and so the International Expedition was now fully re-grouped as a rope of three. We cast off into the immensity of the Allalin Glacier...

Disappointingly, despite all the exertion of the last hour and a half, we were now back to the same height as we had started – so at just over 3000 metres. I didn’t really want to think about the effort involved with 1200 metres still to climb – and a lot of horizontal distance thrown in. Nonetheless I thought I would be alright if I could just plod... and there seemed to be a bit of a trail to follow now, weaving its way from snow-patch to snow patch. But I soon found that I couldn’t just plod. The trail disappeared on the bare ice between the snow patches. And now the big glacier started to live up to its crevassed reputation...

We had to take frequent deviations round gaping holes and chasms. And we found that the snow patches were actually thin skims of insubstantial substance, which often as not overlaid more of said holes and chasms. We had to be very careful - and ensured we had long lengths of rope between us, which we strove to keep tight. There was a need to concentrate – and walking at point, my job of determining the best path was not always straightforward.

![Allalinhorn 4027m from Allalin Glacier]() Allalinhorn 4027m precipitous east face from Allalin Glacier

Allalinhorn 4027m precipitous east face from Allalin GlacierWe were aware of other people on the route now. There seemed to be at least a couple of largish parties on the glacier up ahead. We didn’t see any signs of the Belgian couple, who had set out just in front of us in the darkness of pre-dawn. As it transpired they had taken the more onerous direct route – across the boulder fields – and were now well behind us... so it was a good job I hadn’t managed to follow them after all. Gaining height with almost infinite slowness we passed the precipitous east face of the Allalinhorn, off to our right. It was strange to think that we had been looking down from way up there just the previous day - from the rock step of the Hohlaubgrat.

Some indeterminate time later we left the Allalinhorn behind and encountered the Rimpfischhorn, with an even bigger and steeper east face plunging down from its dinosaur spine. Still at only a miserable 3300 metres or so, we grappled with more complex route finding with a crevasse field in this area. All three of us at some point had the startling experience of snow abruptly giving way underfoot. Thankfully nobody broke through completely, but I have to say I hated these sudden shocks. I have never enjoyed glacier travel because of them – and have always dreaded the thought of a real crevasse fall, dropping into some horrible dark abyss. Keith also was apparently very much on his guard – and barking tersely at Rob every time he felt the rope slacken behind him.

![Rimpfishhorn from the Allalin Glacier]() rgg image: negotiating crevasse field below Rimpfischhorn

rgg image: negotiating crevasse field below RimpfischhornOnly the Peak Monster didn’t seem to mind the crevasses – and didn’t seem at all bothered at the thought of plunging into one. He seemed regard them as mere parts of the furniture – and therefore just something else to accept, much as he did the lightning strikes we had felt on the summit of Mont Blanc in 2013. In due course we found clear evidence that someone else had actually taken a proper plunge... tracks led right up to an eerie looking hole over two metres across – way more than anyone would have attempted to jump – so some poor sod had evidently gone through when the snow had collapsed. Disturbances and boot prints on the other side of the hole were consistent with a (hopefully) successful crevasse rescue...

Still at point, I gave the immediate vicinity of this scary hole a wide berth. However, from the looks of things we still went over what in all likelihood was a continuation of the crevasse and for several metres I found myself holding my breath in anticipation of that sudden shocking plunge - perhaps akin to the feeling a condemned convict might feel waiting for the trap-door to drop open at the gallows...

![Mark, in pain, resting a bit on the Allalin Glacier]() Me, in pain - in place where I felt something go 'pop' in my chest...

Me, in pain - in place where I felt something go 'pop' in my chest...Another reason I really didn’t want to fall into a crevasse was that my chest injury was still very much invading my consciousness - and the jolt of a fall followed by the struggle to climb out could really hurt. I still felt a searing pain to the right of my sternum. And now I was also aware of a sharper more localised pain higher up under my right arm. The constant heavy breathing linked to exertion and our slowly increasing altitude were not helping matters. I felt fortunate in having (thus far) escaped the harsh dry cough I usually develop if I spend any prolonged period above 3000 metres.

With pain and increasing tiredness I needed more rest stops. The other two were tolerant, although both were going well and didn’t really need to stop. At one stop, still breathing heavily, slumped on the snow against my rucksack, I was momentarily disconcerted to hear as well as feel something go ‘pop’ in my chest. With the sharp pain under my arm well established now, I began to revise my earlier impression that I hadn’t broken anything.

As time crawled past we slowly inched our way up the big glacier. Nearly past the great bastion of the Rimpfischhorn now, the gradient of the humpy slopes started increasing. The going became harder, but there was the accompanying reward of much more noticeable gain in altitude, against surrounding peaks. Another reward was that the snow became constant, with no expanses of bare ice, so there was now a constant trail to follow, with an end to all route finding dilemmas. And the ever present crevasse danger seemed to be less – but the occasional subtle dimple in the snow or more blatant hole served to remind us that they were still there – just more cunningly hidden...

With a good trail and less obvious crevasse danger I could finally put my head down and just plod... albeit not very quickly. For brief snatches my mind could wander and take me away from the infernal discomfort. Thus the long awaited Adler Pass appeared gratifyingly quickly at the end. At around 3800 metres we were getting fairly high at last – and it was good to get off the somewhat menacing glacier. Another bonus was a different view: there before us was the Zermatt valley again – from a different perspective and with an even better view of all the summits, since the Rimpfischhorn and the mountain we were on were not blocking part of the view, as they had done the day before. We could see all the peaks of the frontier ridge between Switzerland and Italy - from Liskamm to the Matterhorn. Now only the great bulk of the Monte Rosa massif remained hidden.

![View from Adler Pass 3789m]() View from just above Adler Pass 3789m

View from just above Adler Pass 3789mClimbing above the pass we reached the WNW ridge of the Strahlhorn – and a section of the route which was approaching mildly technical.

“It’s just a bit steeper for the next 200 metres” said Rob, remembering his reading of the map and guidebook “and then it’s just a walk”

The gradient did indeed increase further, but to no more than 40° - and not often above 35°. With a vague crest to ascend and views on both sides, it was more interesting now – and it didn’t seem to take very long up to just below 4000 metres, where the wide ridge broadened still further into open slopes – and Rob’s ‘walk’. For the first time we started to encounter the odd group coming down from the summit. Someone said “an hour” – but right at that moment I’d have preferred “half an hour”...

![At Adler Pass 3789m]() At Adler Pass 3789m At Adler Pass 3789m | ![High up on Strahlhorn]() rgg image: starting to ascend WNW ridge above Adler Pass rgg image: starting to ascend WNW ridge above Adler Pass | ![High on the Strahlhorn normal route]() rgg image: a little further up WNW ridge rgg image: a little further up WNW ridge |

I was aware my slow pace was holding the other two back a little. Keith, concerned that I was in pain, suggested where we were would be safe for me to stop and wait for him and Rob to go to the summit and back... but I made it emphatically clear I was not going to miss the summit after all the suffering. The Strahlhorn was never going to be on my list of favourite alpine experiences – but I bloody well wanted to climb it – and had no intention of climbing the nasty glacier behind us ever again. Apart from a brief stop every quarter hour or so, I managed to keep going, one step at a time. At my slow pace we inched our way across a wide gently sloping plateau towards a rounded hump which I presumed either was or was near to the top. About half way there, I noted that it was the top. A tiny summit cross was now visible, seemingly to the right of the highest point of the hump. The perspective made it seem lower.

When we finally reached the hump the gradient increased again – and we gained what turned out to be a spectacular looking little section of narrow summit ridge. At the end of it and less than 50 metres away was the cross. Happy that the long painful uphill slog was over I stopped and waved Keith and Rob on past me, so that I could photograph them reaching the top of the Strahlhorn, at 4190 metres. My son had got a third four thousander...

![Last 20 minutes to Strahlhorn Summit 4190m]() Last 20 minutes to Strahlhorn Summit 4190m Last 20 minutes to Strahlhorn Summit 4190m | ![Last steps to summit of Strahlhorn 4190m]() Last steps to summit of Strahlhorn 4190m Last steps to summit of Strahlhorn 4190m |

For such a great sprawling bulk of a mountain the summit came as a surprise. It was remarkably small and dominated by a sturdy looking aluminium cross, well over a metre tall. There was standing room only – and thoughts of being able to sit down and get some lunch out were soon dispelled. Besides which, right up on the top now, there was cold breeze coming across the crest, which had not been apparent down below.

![Strahlhorn summit 4190m]() Keith and Rob on Strahlhorn summit 4190m Keith and Rob on Strahlhorn summit 4190m | ![Keith and Mark on top of Strahlhorn (4190m)]() rgg image: Keith and me on summit rgg image: Keith and me on summit |

The view was excellent. And actually it really needed to be after the infernal, dangerous, painful (for me) and above all long ascent to reach the top. The big glacier with all its horrors was now far below and seemed to stretch virtually to the horizon. The Britannia Hut should have been visible, but was lost behind cotton wool balls of cloud – bubbling up from well below our level. I noticed the cloud was in two layers. There was the interrupted jumble of the cotton wool balls below, but overhead there was a streaky overcast which blocked some of the sun and added a slightly murky tinge to the light. The weather was clearly still far from settled. There had been a few lenticulars in the sky earlier – and sure enough another front was on the way – but the rain held off until very late next day.

Summit views:

![Strahlhorn 4190m summit view]() Strahlhorn 4190m summit view - looking back down on the interminable way we had come up

Strahlhorn 4190m summit view - looking back down on the interminable way we had come up

![Strahlhorn summit panorama stretching from Monte Rosa to Matterhorn]() rgg image: looking the other way to a summit panorama stretching from Monte Rosa to Matterhorn

rgg image: looking the other way to a summit panorama stretching from Monte Rosa to MatterhornThe main part of the view which absorbed me was down the opposite side of the crest to the side we had ascended. Now at last we had a grandstand and even aeroplane view of mighty Monte Rosa – looking over the tops of the Cima di Jazzi and some other three thousanders that Rob and I had traversed as an acclimatisation exercise the previous year, before climbing the big one. I took a couple of photos and was preparing to take another when Keith distracted me. He had stripped off his windproof clothing layer toiling up the slopes below – and now the cold and even icy breeze on the summit crest was penetrating his fleece. With his very slim build he is vulnerable to the cold and cools down very quickly. He needed to get a layer on and also eat something to get himself warmed up.

“Rob – Keith is cold – why don’t we drop down off the summit now and find a sheltered place to get some food and let him get some warmer clothes on...” But the Peak Monster wasn’t listening... what the hell was he doing?

He had decided that despite the great sturdy construction of the aluminium summit cross that we weren’t on the highest point of the Strahlhorn. His attention was now further along the narrow crest – where he had decided the highest point was - at a point on the horizontal ridge about 25 metres away...

“C’mon Rob, Keith’s cold – we need to get down – you don’t need to go over there!” Bloody ridiculous! The Swiss had planted a dirty great construction of a summit cross on the TOP of this mountain – and they weren’t going to have put it in the wrong place... they had a national reputation for extreme accuracy in this country... they made very accurate clocks... and their trains ran bang on time to the nearest second...

But the Peak Monster had already made his decision. A citizen of the flattest country in the world he was going to challenge the Swiss surveyors. He was going to go over to where he had determined the highest point to be. No other tracks went that way and the crest looked awkward as well as exposed – with narrow bits of rock ridge as well as snow - but that wasn't going to deter him. Peremptorily he clipped both Keith and I to the well anchored summit cross and gestured for me to somehow belay him, although the cold hunched figure of Keith was in the way - and the rope was in a disordered jumble beyond him.

![Strahlhorn 4190m summit view]() The Peak Monster at the place he had determined was the summit...

The Peak Monster at the place he had determined was the summit...Without waiting to see if I was belaying him, the Peak Monster, driven by the forces which have propelled him up so many peaks, set off towards his goal. He paused briefly to shake out the tangles from the disordered rope – and most of it fell off the side of the ridge in a great loop. Then he balanced carefully along a narrow bit of snow, before dropping down on all fours to negotiate a small rock section. Bit by bit he picked his way along...

Keith was cursing quietly. We had no choice but to wait.

Several moments later the barbarian Dutchman reached his goal. He straightened, turned and his faint voice drifted back to us...

“Take some photos!”

Operating on reflex I took a photo, although another parallel reflex suggested I tell the ruffian to stick his photo in his bottom.

Several more moments later he returned. I had made a half hearted attempt to take in rope - but with all three of us tied to the cross, nobody was going to get very far anyway, in the unlikely event Rob slipped. Then, my over-reaction accentuated by fatigue, altitude and pain as well as my fatherly concern for Keith, I ranted and raved at him – until the absurdity of the situation penetrated. This was really no place to have a fall out - and I calmed down fairly quickly.

The Peak Monster said nothing. It is a point of honour for him that he has to touch what he perceives to be the highest point of a mountain to be satisfied that he has made the ascent.

Finally, after we all sorted out the rope, Keith and I got ourselves detached from the big metal cross – and the International Expedition, a little ruffled, moved off back down the ridge away from the summit. We descended about 50 metres to a shallow bit of slope in the sun – and out of the wind. Now we could get some food and clothing out without risking it dropping 1000 metres down the east face onto the glacier below.

It was good to be able to rest properly at last. But the rest could not be for long. We now had the infernal Hohlaub Glacier to descend. If it had been booby-trapped with dangerous crevasses on the way up, when everything was supposed to be frozen, it was going to be even worse on the way down, with the snow softening in the sun. At some point in the morning each of us had experienced a boot plunging through a weak crevasse roof. It seemed rather likely that at some point on the return we would be practicing crevasse rescue skills...

We set off downwards. Fairly early on we passed the Belgian couple still going up, despite having set off in front of us that morning. Somehow they had come to be a long way behind us – despite my slow speed. We later found out that in the darkness, they had taken the direct route across the boulders... so it was a good job I hadn’t succeeded in my attempts to follow them...

The big glacier was nearly as annoying as expected. It was every bit as long. The snow was soft. But on the plus side, following advice from one of the descending parties we had spoken to on the way up, we had taken a slightly better line – and circumvented one of the worst bits. And the other good thing was that contrary to expectation nobody had a proper crevasse fall – and (perhaps to the disappointment of the Peak Monster) we did not get to practice our crevasse rescue techniques. But we nearly did...

![Panorama of Strahlhorn (4190m) and Rimpfishhorn (4199m)]() rgg image: looking back up to the long weary trail descending from Adler Pass

rgg image: looking back up to the long weary trail descending from Adler PassLow down on the nearly level section of the lower glacier I let my guard down (for the second time that day) – and made an unwise boot placement onto a patch of old snow. I should have known better – we knew these yellowing 'scabs' couldn’t be trusted. The inevitable happened and I plunged through – until stopped by my rucksack. I was in to below my waist – and my legs were wheeling in space over an invisible horror below. Jesus!

Behind me, I knew that Keith and Rob would have the rope tight... but I still did NOT want to end up inside whatever nightmarish maw beneath, even if I was prevented from going far. Momentarily frozen with horror I galvanised myself into careful movement... I still had my walking poles in my hands and releasing the handles, I shuffled my grip along the shafts until I could grip each just above the ski baskets near the ends. I could now use the points like unwieldy ice-daggers. Fear enabled me to ignore what it was being done to my fractured rib – and I stabbed both points into the ice in front of my face – and pulled for all I was worth... I moved about 10cm... better than nothing. Releasing one point I stabbed it in again at the extent of my reach, quickly followed by the other – and pulled again – really pulled – and got another 10cm...

Bit by bit I hauled myself out of the crevasse. I lay winded face down on the rough gritty surface of the glacier. Pain now blazed in my chest – and I was reminded in the harshest way yet, that I really had broken a rib...

Keith and Rob waited patiently for me to recover – and then steered a wide course round the hole I had just made. Nobody else took a plunge. A short while later we worked our way through a final maze and stepped off the glacier onto the boulders at the side – near where I had taken my little trip eleven hours earlier. We still had about another hour and half to go, before reaching the hut. And there before us was the next obstacle: the 70 metre high boulder slope to climb. But this time we all removed crampons and the rope. I for one didn’t fancy tripping over again. Then somehow, we reached the top of the slope at the col between the Hohlaubgrat and the little rognon. We traversed the 300 metres of mixed rock and snow to the next and final spur before the anticipated scramble down to the Allalin Glacier. At this point we stopped for a brief rest by the cairn marking the top of the descent – and Rob looked critically down at the route I had steered for us across the glacier, in the darkness of the early morning.

“I think we could have followed a better line” he said bluntly – and gestured a more curved route taking in a black dot in the middle of the ice – “I think that black thing is a marker”