|

|

Area/Range |

|---|---|

|

|

41.51179°N / 19.83917°E |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Trad Climbing, Sport Climbing, Toprope, Bouldering, Ice Climbing, Aid Climbing, Big Wall, Mixed, Scrambling, Via Ferrata, Canyoneering |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

I. Mountain and Rock Climbing in Albania

Ne bjeshke, ne vrri e ne kujri, si te katundit si te flamurit gja s'i shitet e pjese zotnimi nik mundet me pase kurr; sa per kullose e per dru e almiste i nepet lirija e perdormit per ndere.Nothing may be sold or become private property in the upland or lowland pastures or in the common property of the Village and Banner, because these are free for the use of everyone...Kanuni i Lek Dukajinit, LV.229

Sketch of Contents Below

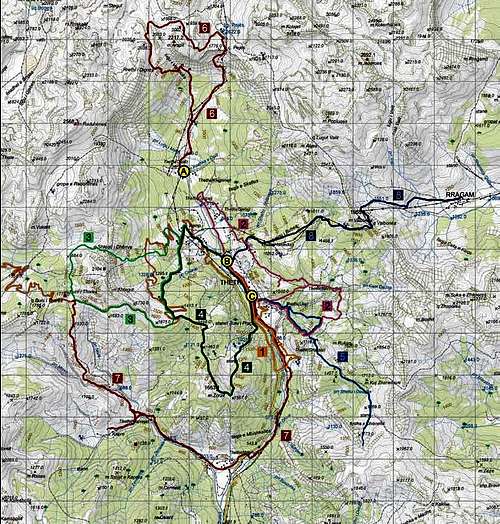

The materials below provide details how to to access and enjoy some of the major rock and mountain climbing areas in Albania, viewed against the context of its unique and ancient cultures of highlanders and mountaineers. It works geographically out from the capital region of Tirana and its nearby mountain town Kruje northwards and eastwards into the 'Albanide' or Albanian 'alps.' These are perhaps most properly the southern portion of the Montenegrin limestone plateau of the Dinaric Range of jagged limestone mountains which from Albania reach north into Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina (where the formation from which the name 'Dinaric' derives), and the other new nations of the former Yugoslavia. The table of contents to the right indicates the various chapters of the text according to the region or district of Albania covered. Some of the areas are associated with annotated maps, and the relevant photographs have asterisks and italics to indicate the annotatations on the associated numbered maps. Thus, italics followed by a number and asterisk indicate that this image or area is marked thusly on the relevant numbered topo. Many of the photographs, especially those introducing areas or gorges or mountain basins, indicate their locations via the Google Maps tele-atlas associated with SummitPost. Where position of features in terms of degrees and minutes North and East are provided, these can serve to locate the feature in the center of a quad on Google Earth, Panoramino, etc. at those enumerations. For quick orientation, as descriptions begin in terms of District borders and their chief towns, a map is provided at the end for those who don't have Albanian geography in perfect memory, with district towns marked and district borders in green. AMapy.CZ provides a useful road map, marking the main routes and the main towns described below which could be opened in a separate tab while reading for orientation purposes.

Note on Communication and Spelling

In asking directions, it is useful to keep in mind that Albanians nod 'no' by shaking their head up and down, and 'yes', a much more frequently seen expression, by nodding their head sideways, with a slight figure eight bob and generally a smile, reminding one of the Indian subcontinent perhaps. The Albanian language is odd to pronounce and spell, as much due to the strange orthographic form it took when it was written down under the influence of 19th century central European nationalism as the circumstance that, it constitutes its own unique branch of the indo-germanic languages. But like languages with recent orthography, it is at least completely consistent. Unfortunately, local differences in Albania and general unacquaintance with the language outside means that spelling, especially of territorially relevant proper names, can be confusing, particular since many of the territorial names are either ancient or of foreign extraction, and all the languages in the area have complex word-ending patterns that will then 'appear' different when transliterated. For simplicity's sake, I generally use Albanian words, albeit without their linguistic accent marks, and only include the Slavic or Greek terms in parentheses on the first occasion where the relevant peaks are in the immediate vicinity of the relevant border; where there is real lack of clarity or substantively different names or name dispute relating to Albanian, to the other regional languages (Serbo-Croat, Macedonian, Greek), or to translating this in to English, attempt has been made to indicate the issue so that a word search to the first or most important usage provides clarity.

==

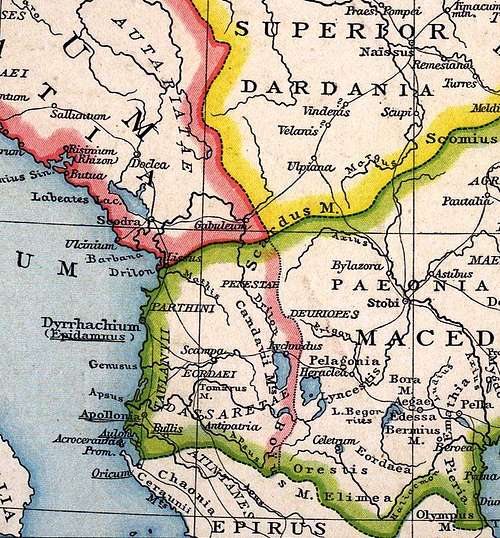

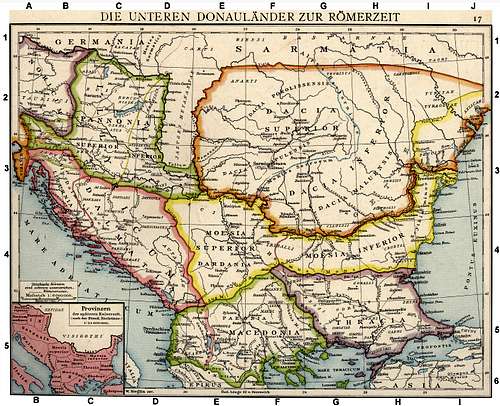

An old map of the lands south of the Donau during Roman times. Illyricum amongst the Roman Provinces

==

SummitPost already has a useful table of some expressions charted in Albanian, German, English, Italian and Serbian (which itself is similar to Macedonian). Mal (often with an ending, e.g., '-i' for singular and '-a' for feminine) is 'Mount'. Maj, likewise, is 'peak', fushe is 'field', and qaf is 'pass'. Since 'peak' in English nearly always refers to a related subsidiary summit (e.g., Mt. Wilson, Wilson Peak), its more common use in Albanian for major summits should be kept in mind, related to the fact that more than usually Albanian mountains are pointed at the top rather than rounded. Thus the Maja Jezeres, the tallest peak in the northern Accursed Mountains, is more precisely 'Jezerce Peak', with 'Jezerce' derived from the Serbo-Croat word for 'lake', jezero; it has traditionally been called 'Jezerca' in German and 'Crête du lac' in French. Literally in English this would be 'Peak of Lakes', given the beautiful glacial lake basin from which it is most spectacularly viewed, just to the north and just inside the Montenegrin border from which the peak has been most often approached via the Ropojana. But for the purposes of recognition, whether you read this name as 'Mount Jezerce' or 'Jezerce Peak', with or with out Slavic or Albanian endings, one is speaking about the same item, as long as the '-ë' ending is pronounced with a short 'a' sound, thus 'Ye-Zer-Cha.' The definite singular ending '-i' is also, as in many European languages, used as a familiar, like Joan 'Joni' Mitchell, or Daniel 'Der Dany' Cohn-Bendit - thus e.g. the Albanian first name Bledar as 'Bledi.' Names appear on the map infinitively, but a spoken definitively, thus 'Kukes' and 'Kukesi.' Finally, 'Albania' is derived from Latin, indeed is for instance also the old expression for 'Scotland' even though of course it is also a much older expression for Albania; the Albanian word for 'Albania' is Shqiperi and for Albanian is Shqiptar, which also means 'eagle' - thus 'land of the eagles', which will of course be more meaningful at some point when the species recovers to more than token size...

==

Mt. Kokkervates in the Jezerza Group as seen from the Montenegro approach.

==

Introduction to Climbing in Albania

Geography and Geology

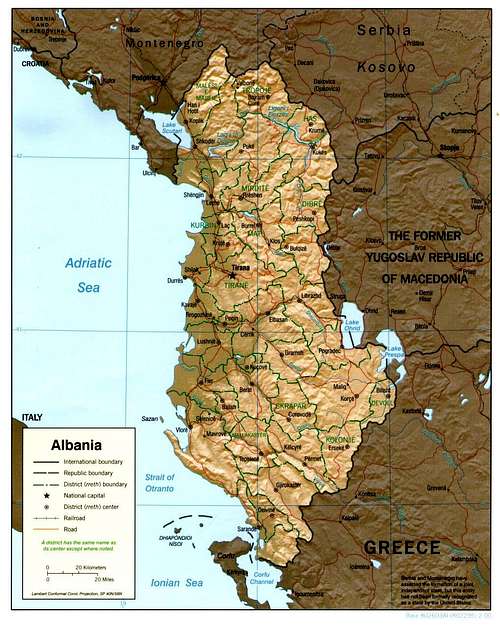

Albania is a small mountainous coastal republic lying on the Adriatic Sea. It is bordered in the south by Greece and in the north by the countries of former Yugoslavia -- by Montenegro in the northwest, by Kosovo in the northeast, and by Macedonia in the east. Seventy percent of the country is mountainous, frequently rugged and inaccessible. Administratively, the country is divided into twelve Quark or 'prefects'/'counties' and 36 Rrethe or 'districts.' The Rrethe are roughly comparable in size and to their equivilent in the United Kingdom or to what are called 'municipalities' in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, but with more strongly felt differences. Where an Englander from an obscure town or village would be from their 'county' to establish recognition, or a Greek from their Prefect or even Perifery, an Albanian is more likely to specify the District, which also provide a more precise unit for characterizing the distinct and changing mountain environment of the region.

The mountainous character is evident by viewing a chart of the high-points by District: insofar as while no peaks are over 2800 meters(m), only two of the twelve Prefects have highpoints lower than 2000 meters (6500ft) and many many peaks are in the 2500m (8200ft) range. A full third of Albanian territory is over 1000m (3300ft). Most of this mountain material is Dinaric or Hellenide limestone that constitutes the essence of the climbing environment, though through much of the central uplands in from the coast, a serpentine base to the geology is predominate; and this is then often mixed sharp limestone and sandstone outcroppings which rise out of the dull green, spotted and rounded appearence of serpentine based formations.

However, insofar as the limestone mountains of the Balkan peninsula constitute the central aspect of Balkan highlands, whether 'Dinaric' or 'Hellenide', this character stretches right through Albania, with the highland and mountainous border with Macedonia down its Western side and into Greece constituting one continuous mountain formation, broken only by the cut path of the Black Drin river, and thus forming the central backbone of the range in this part of the Peninsula, the same backbone which to the south becomes the 'spine' of Greece through the Pindus (Pindos) Range in Greek Ioannina and Epirus.Running south, this spine includes the peaks of Maja e Tommorit (2415m), Vithkuq (2383m) in Albania, the spectacular Grammoz (2520m) on the border with Greece, Smolikas (2637m), Astraka (2432m) and Tymfi Oros (2497m) on the Greek end of the same 'spine.' Going north this includes the ridge of the of the Jablanica mountains dividing Macedonia from Albania south of the Drin, and the Korabi Range rising north of the Drin along the same international border line to Velivar (2375m) and the heights of Mt. Korabi (2764m) - the highest peak in the Dinaric range - on to Gjallica (2486m) and Koritnik (2384m). Here geologic formation splits off: north-east it becomes the somewhat different Sar Planina(Shar Planina) reaching north along the Kosovo/Macedonia border above Tetotva (Tetovo). The Dinaric formation proper, however, angles eastwards where Albania meets the border of Kosovo, via the Mali e Hasit and Malesi e Djakoves into the 'Accursed Mountains'(Bjeshket e Namuna in Albanian, Prokletije in Serbo-Croat) north-east of Bajram Curri - the wild and beautiful 'northern Alps' in the borders of Albania with Kosovo and Montenegro including such peaks as Shkelzen(2409m), Gjeravica/Deravica (2656m), Tromedja (2366m), Jezerce (2693m), and the lower but spectacular Karanfili (2119m).

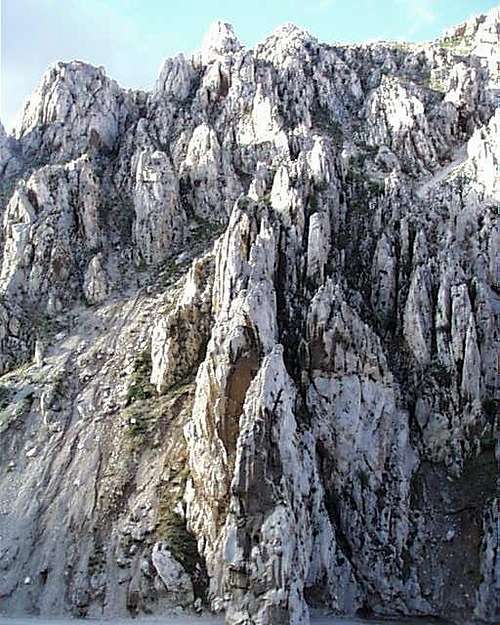

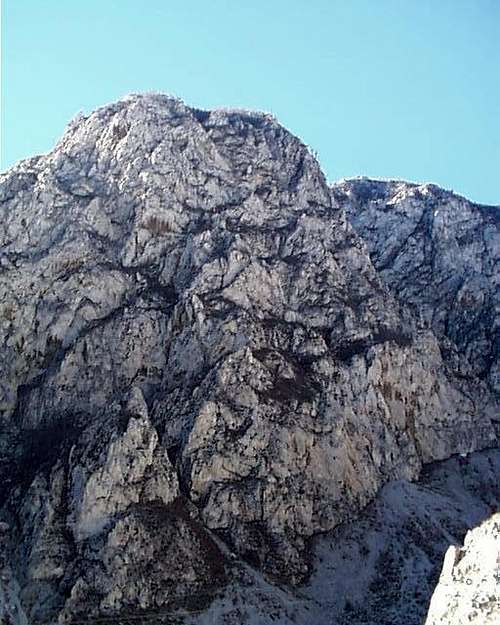

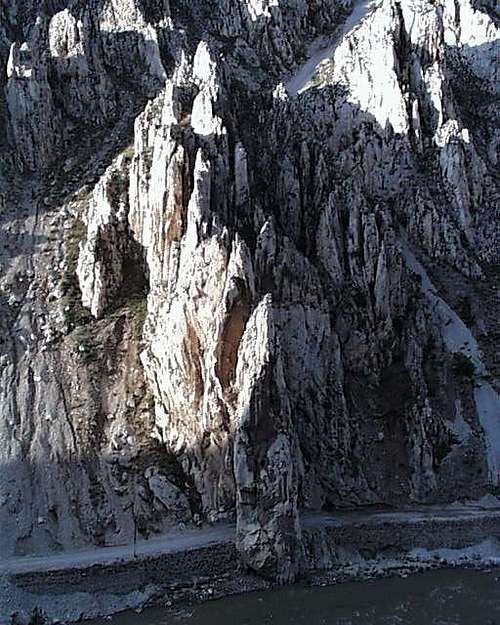

The rugged limestone character in the Albanian portions is most distinct in the north, with the 'white' of this geology mixing with the more broken 'green' serpentine and 'red' sandstone as one goes south.Though its main mountains are limestone extensions of the Montenegrin Plateau, Albania's northern mountains are more folded and rugged than most of that plateau. The rivers have deep valleys with steep sides and arable valley floors. Thus, though the successive north-south ranges of uplifted carst and limestone rarely reach over 2500 meters, the steeply ridged and steep sided nature of these mountains, combined with the precipitous gullies carved through the underlayers of flysch, provide an unusual geological environment unique in Europe. Some of these places where streams have carved through the limestone backbones of the country are so smooth and vertical, they appear cut as if by a gigantic jigsaw. Albania owes its involved structure and intricate features partly to the complicated folding of its rocks, but chiefly to its copious rain and snowfall. The accompanying drainage patterns have given rise to a remarkable river system, combining long trough valleys eroded in the softer beds, with precipitous gorges cut through the harder rocks between them. It is in the superfluity of such gorges and in the dolomite-style limestone ridges and faces carved geologically by the same forces that Albania provides good rock climbing possibilities.

==

Mt. Stogut - a distinctive part of the Radohimi group - first recorded ascent by Austrians via a chimney in the north side.

==

Style of Rock Climbing

Nearly all the rock climbing is on the steep limestone faces and ridgelines carved out by this geography. Long but steep broken backbones of rock and accompanying cracks or gullies cut across the limestone faces, providing the typical lines of first interest in the formations. Between these, the limestone frequently drops in vertical faces of varying quality, with the overhanging portions generally visible by the extremely abrasive limestone covering caused by water drainage and leaving such portions of stone a distinctive dark reddish or dark brown. Long fourth and easy fifth class lines can, depending on the rock character, be broken by short overhang steps forcing detours or sometimes exciting traverses where the broken crack-ledge systems disappear into steeper rock or cross harrowingly above it. Probably the most 'cragging' fun can be had moving swiftly up the long limestone ridge lines, especially when they disappear over the horizon or end up in some broken partial summit with awkward or confusing descents. Though of varying solidity in places, there is much rock dropping right down to road beds which is steep and offers muscular liebacking and crack climbing of a much more committing sort. Protection is sometimes sparse, and much of the face climbing is unprotected. Vegetation and crack systems, as well as horns and spikes of limestone on the ridgelines provide more options when following the more obvious lines. A crag hammer or some other kind of substantive gardening implement is quite useful, together with many slings and some common sense.

In the summer an ice ax is rarely essential in most places, but even a little bit of snow, if it sticks for any length of time and freezes, can make the steep crumbling limestone hillsides positively terrifying, especially the rather common sorts with long steady fall lines, and when the limestone starts mixing with the much more uncertain flysch sandstone layers of the geology.

If proper care and appreciation of the rugged conditions is taken into account, the possibilities for exploring and developing new lines of many lengths and in all degrees of difficulty are manifold. In particular, long half-day or all day fourth and fifth class ridgelines rise up the sides of the steep limestone peaks are a characteristic option for this region. Many prospects require long and sometimes harrowing approaches up steep hillsides and even steeper shoulders of crumbling limestone, carst, and those especially when mixed with sandstone and serpentine. Some such areas appear as scree fields but turn out to be solid bands of rock whose surface is composed of sluffing off sheets of sharp edged limestone pebbles. Where proper care on approach or descent is taken, inspiring, sometimes easy but frequently devious, long and meandering lines of ascent can be found. The entirety of highland Albania is criss-crossed with goat and livestock trails. While the roads are still remarkably and nearly universally in the most terrible conditions, the manner in which they – whether unused mining track or main thoroughfare – cut through and across steep escarpments and precipitous gorges guarantees many places throughout the country with spectacular routes up unclimbed limestone straight off the road-bed. Through most of highland Albania covered in the pages below, cragging, bouldering, and scrambling is readily available in every shape and variety.

Overview and Some Details on the History of Climbing in Albania

The main advantage of climbing in Albania is the rugged and completely isolated nature of the environment, combined with the fact that almost none of these rocks have had their potential developed or their lines ascended. During its first two decades of existence as an independent state, Albania fell more or less within the Italian sphere of influence; and this is reflected in the large numbers of neo-classical government buildings in the capital and the role of Italian mountaineers who scoped out and ascended the more inaccessible of the northern 'Accursed Mountains' (Bjeshket e Namuna or Prokletije). In general, exploration of the mountains has related to the imperial priorities of the various surrounding European states but this really did not begin until the 20th century.Though local mountain clans have occupied the arable mountain valleys for three millennia or more, Albania has been for ages remarkably unknown in the highland. The Albanian cities of Durres and Shkodra have classical foundations, and for centuries were independent or semi-attached commercial cities integrated into or allied with the Venetian Republic, known then respectively as 'Durrazo' and 'Scutari.' But much of the Albanian coastland, like elsewhere in the Mediterranean, was infested with malarial swamps, and this kept the highlanders relatively isolated from coastal traffic, and also unknown to outsiders. As the contemporary mountain author Tomislav Cezener has amusingly pointed out, the Austrian military maps of the Accursed Mountains from the crucial years of the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars were almost completely bereft of details. For years, Mt. Shkelzen, distinctly visible high above the town of Tropoja on the commercial road into Kosovo over Qaf Morine, was considered the highest summit of the range. One of the first researchers of the area, Hungarian geologist Franz Nopcsa, visited the central Bjeshket e Nemuna in 1905, as the country was slipping out of Ottoman control, and into the eyes of the also already shaky Austro-Hungarian influence. He picked out the much more inaccessible Mt. Jezerce, located on the high ridge line between the high mountains Districts of Malesi e Madhe and Tropoja, and just inside the border of Albania from Montenegro, as the highest mountain of the whole range. Nopsca was also a Hungarian Baron, at one point sought the Albanian throne (later given to a useless German Prince), and published during his lifetime some 50 articles and monographs on Albania concerning linguistics, folklore, ethnology, history, and the kanun, the key text of Albanian tribal based folk law (Gezim Albion, Franz Nopcsa and his Dream for the Albanian Throne[2002]). He revisited the area in 1907 with instruments and confirmed his claim that Jezerce was higher than Shkelzen. In the wake of Nopsca's first adventures, Albania largely fell into an Austro-Hungarian sphere of influence, and as a result it was explorers and mountaineers from these areas which took the lead in the early 20th century. By early summer 1929, all major summits in the Bjeshket e Nemuna range had been climbed and measured by Italian surveyors. A week or two later, the first mountaineers, three British climbers (Sleeman, Elmalie and Ellwood), summited Mt. Jezerce on July 26th 1929 via its hard 2nd class or easy 3rd class standard route. A couple of years after that the peak was scaled by group of Austrians who also progressively surveyed and traversed the ridges of the Albanian accursed mountains, and climbed the main peaks, outlying peaks and towers systematically including the Radohimines group, Mt. Viavet, Mt. Boshit, Mt. Popluks, Mt. Shkurz, Maja Briaset, Maja Rogomir, and other the peaks in the Thethi and Valbona basins. (Egon Hofmann, 'In den Nordalbanischen Alpen', Oesterreichisches Alpenzeitung, Vol. 54 , 1932, pp. 171-187.)

Besides a series of expeditions sponsored by the Austrian Alpine Association, several German groups made trips in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and somewhat later, Italian mountaineers were also active.

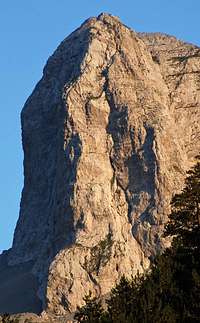

==

Maja Briaset - alpenglow on the main or Valbona Face, first climbed by Pimper and Poppe in 1959

==

Some Early Ascents - Peaks Party Date UIAA

| Maja Zuri | Schaller and Schaefer | June 1934 | V |

| Maja Arapit, East Ridge | Hoffman, Feinsheimer and Schatz | June 1930 | I |

| Maja Boshit, Main Summit and traverse to secondary summit via north-south ridge line | Hoffman, Feinsheimer and Shatz | June 1930 | III |

| Maja Vinchen | Bauer, Huettig, Martin | June 1934 | I |

| Maja Papluk, North Ridge | Bauer, Huettig, Martin | June 1934 | II |

| Maja Radohimes, North Wall, Southern Summit | Fink, Tinsobin | Aug 1933 | V |

| Maja Briaset | Bauer, Huettig, Martin, | June 1934 | I |

| Maja That, Northwestern Ridge | Bauer, Huettig, Martin, Obersteiner | June 1934 | IV |

(Hoffman, 'Albanienexpedition 1931' Austrian Alpine Journal, vol. 53, pp. 327-334; Obersteiner and Hoffman, 'Fahrtenbericht aus den Nordalbanischen Alpen', Austrian Alpine Journal, no. 57, 1935, pp. 18-22.)

==

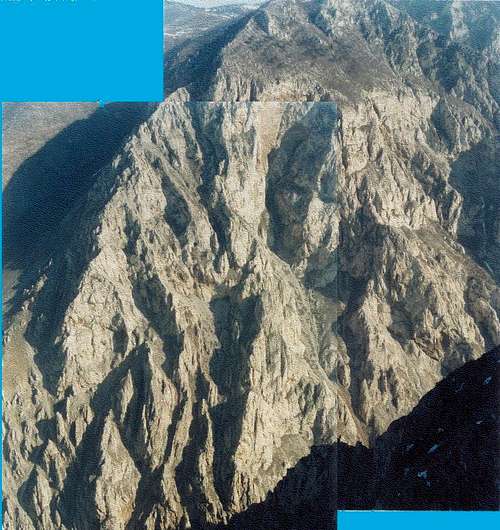

The upper sections of Mt. Jezerce viewed from the north, and showing the character of the 2nd-3rd class 1929 walk up route of this, the highest peak in the Accursed Mountains. Photo courtesy Petter Bjorstad.

By the late 1930s, however, mountaineering in the Accursed Mountains tailed off. The Croat, Branimir Gusic, creator of the first Dinaric mountain movie, ‘Durmitor’, a human geographer by profession, spent considerable time between mid 1930s and late 1960s researching the massif. He scaled Maja Kokervhake (2508m) just north of Jezerce and collected large and unique collection of Malisorian craft and art samples as well as various items of everyday use. His ‘Malisorian collection’, was exhibited for years in the Zagreb Museum of Ethnography, before disappearing in more or less mysterious manner. He was, as Cezener notes, an ‘unsung hero of the Dinaric Alps.’ Sometime on the eve of World War II, the area was visited by Italian mountain climber Pietro Ghiglione - better known as an one of the innovators of ski mountaineering in the Alps and Himalaya with his friend Ottorino Mezzalama, as well as his climbing in the African Ruwenzori when he was well over 70 years old. Ghiglione wrote Montagne d'Albania (Edizioni Distaptur, Tirana, 1941), perhaps still, in Cezener’s view, ‘the best Albanian mountain guidebook.' (See Cezener's excellent Maja Jezerces SummitPost page from where most of this material is drawn.) Later, during World War II, there are, amusingly, various reports from H.W. Tilman’s colleagues in the guerrilla liaison ‘Special Operations Executive’ or SOE operating in the Balkans. Tilman, more famous for his exploits on Mt. Kenya, Nanda Devi and Everest before World War II, was one of the operatives traveling in 1943 through the mountain areas of Albania on donkeys laden with radios and bags of Napoleonic era gold sovereigns. His main job helped organize partisan opposition to the Italians and the Germans. SOE, though legendary, had mixed success in Albania in contrast to Tito’s Yugoslavia due to the growing and radically Stalinistic xenophobia of the Enver-Hoxha-led partisans together with the greater influence of Tory-sympathizing operatives in the SOE groups that were operating in the north sections of Albania and Kosovo out of Greece. But Tilman, who seemed less than interested in guerrilla war and most sympathetic to the scattered Vlach nomadic herders of the Southern Albanian mountain ranges, did manage to maintain a regular weekend exercise regime in his spare time from being a guerrilla band organizer -- by bagging Albanian peaks on his own (Tilman, When Men and Mountains Meet, London, 1946).

Mt. Boshit (2416m) guards the pass between the Thethi and the Valbona Valleys. The western wall (UIAA VI-) was done in July 1959 by Harry Duerichen, Harald Loebe and Minella Kapo. The Northern Pillar (UIAA V-) was done in July 1960 by Eberhard Nitzwche, Vassili Wreto, and Joachim Soehler.

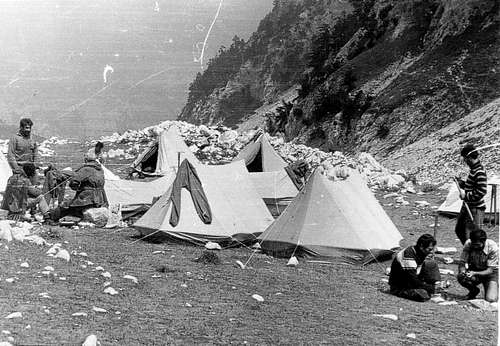

Mt. Boshit (2416m) guards the pass between the Thethi and the Valbona Valleys. The western wall (UIAA VI-) was done in July 1959 by Harry Duerichen, Harald Loebe and Minella Kapo. The Northern Pillar (UIAA V-) was done in July 1960 by Eberhard Nitzwche, Vassili Wreto, and Joachim Soehler.Once the British left, however, the historical record of mountaineering and especially rock climbing, is sparse until a series of East German summer expeditions in the Summers of 1959 and 1960 led by such well known climbers as Harry Duerichen, Christel Stuntz, Fritz Eske and Rudi Pimper. These initiatives combined with the development of local Tirana based Alpine Association which ran two week courses in the Theth Valley during the summer times.

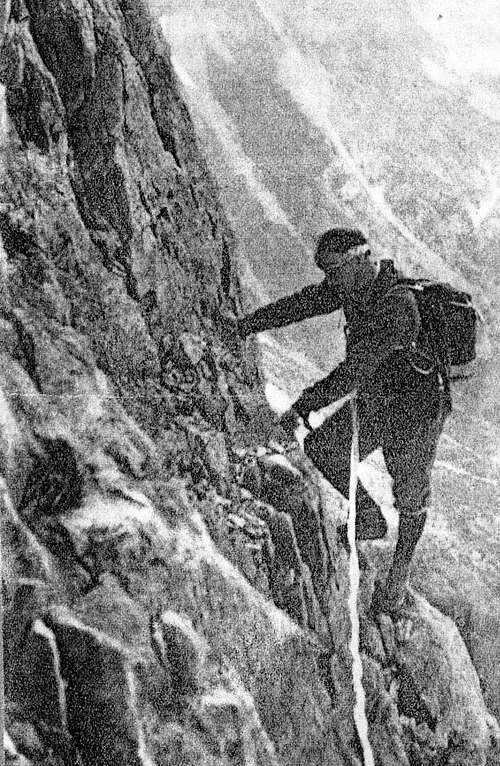

The east Germans ascended most of the major limestone features in the valleys of Theth, Rapolinia and Valbona during these Summers. Schmidt, Duerichen, Eske and Loebe, along with Albanians Minella Kapo and Petrop Kuli climbed the south western, north east and north western faces of Mt. Arapit, as well as well as two lower portions of the main Southwestern face. They also climbed the north and north western ridges of Mt. Papluk, the West face and north pillar of Maja Boshit, the two peaks of Viavet, the northern face and northwest pillar of Radhohimes, as well as the huge north west and valbona faces of Maja Briaset and Maja Gruk e Hapt in the Valbona Valley. These two summer still constitute the single most intensive period of mountaineering development and advances in the entire history of climbing in Albania, as the summary of the achievements below illustrates. (See Peter Popp, 'Zarabitwand', Unterwegs, no. 10 [1960]; Hans Pankotsch, 'Nordalbanische Alpen 1959/1960', Elsasserstr. 3, Dresden; Peter Popp, Bergfahrten im Land der Skiptaren, Goes, 200, 23pp.)

==

Maja Briaset - Renowned East German mountaineer Fritz Eske seen here on the first ascent of Briaset's huge north-east face in 1960.

==

Notable Ascents Party Date UIAA

| Maja Boshit, Westface | Duerrichen, Loebe, Kapo | July, 1959 | VI- | |

| Maja Boshit, North Pillar | Nitzsche, Soehler, Wreto | July 1960 | V- | |

| Maja Vinchens, Northwest Ridge | Daeweritz, Schoenberger,Wreto | July 1960 | III | |

| Maja Vinchens, Northeastpillar | Soehler, Nitzsche, Schmidt | July 1960 | V | |

| Maja Rushkull (2560m), East Face | Duerrichen, Stuntz | June 1960 | V | |

| Skiptar Tower, East Crack | Poppe, Pimper | July 1960 | V | |

| Skiptar Tower, Northeastern Face | Stuntz, Duerrichen | July 1960 | IV+ | |

| Maja Kolet, Southwestern Dike | Soehler, Nitzsche | July 1960 | IV | |

| Maja Radohimes, North Face | Eske, Loebe | July 1960 | VI | |

| Maja Radohimes, Northwest Pillar | Pimper, Popp | July 1960 | VI | |

| Maja Gruk e Hapt (2425m), South Face | Pimper, Popp | July 1960 | V+ | |

| Maja Briaset, North East Dike | Nitzsche, soehler | July 1960 | IV | |

| Maja Briaset, Northwest Gully | Eske, Loebe | July 1960 | V | |

| Maja Briaset, Valley or Valbona Face | Popp, Pimper | July 1960 | VI |

After the Albanian government broke with the Eastern Bloc in the early 60s, the Albanian Alpine section continued its summer and its winter camps in the Accursed Mountains, and eventually did many independent ascents both by themselves, and with later Chinese collaborators. Most notable of these was the grade VI 'Master's Route' up the south face of Arapit by Ilir Tapir and Sokel Dokel in 1985.

The Albanian Special Forces Military Base was located during te 1980s on the Zall Herr Road, and various pitons and bolts have been found in the valley above, where they developed some of the cli bming for training purposes. But with the exceptions of the main peaks, and the traditional places on Mt. Daiti and in the Thethi and Valbona Valleys, very little of the immense climbing potential of Albania has been really explored, muich less developed. It remains even today almost completely unexplored and undeveloped as a rock climbing area.

The steep hillsides, fracturing limestone ridges, and lack of climbing traffic means that much of the terrain is extremely exposed, with copious precarious rock - from pebbles to giant blocks - perched about in the most spectacular places. Particular care on steep talus and scree fields of the crumbling limestone, carst, or composite hillsides is merited. Only a few small stones can start spontaneous rockslides loosening large blocks and falling hundreds of meters upon goat paths or mountain roads below.

==

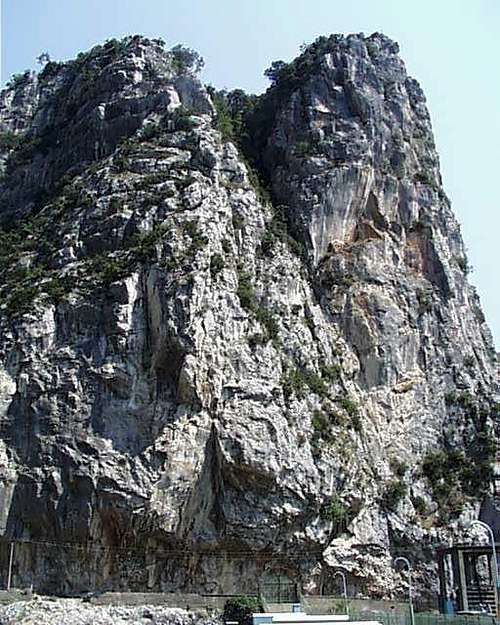

A pinnacle at the entrance to Bovilla gorge. Circa. 2001 this contained the only piece of fixed protection I found in Albania. It protects a 5.9 move off a shelf from the back. It has since been destroyed by open pit lime mining operations.

==

The Evolving Park System in the Mountains - Beginnings and Development

Many of Albania’s mountains now lie in established national parks. The first of these was the 4000 hectare Tomorr National Park, established (strategically) south of the Skhumbi River in 1956 in the Tomorr Range in middle of the country just east of the beautiful museum-city of Berat in 1956, and overlooking the notorious secret arms production city of Polican.

==

The medieval castle of the museum town of Berat, with the Tomorrit Range rising in the background - a typical hazy Albanian day. - photo Bethany Sanders

==

Mt. Tomorrit in Tomorr National Park - Hassan Duro of the Tirana Section of the Albanian Mountaineering Association, at the Summit in the 1970s.

==

In 1966, three more parks were established in Albania’s mountain ranges:

1)Daiti National Park, 3300 hectares of the mountain overlooking the capital, Tirana (also in the vicinity of military installations),

2)Theth National Park in the Shale basin around Theth (2630 hectares), and

3)Valbona National Park, in the Valbona Gorge from the gorge entrance through to Rrogram and the surrounding mountains (3237 hectares).

Since the end of the Cold War, the Albanian government has been busily detaching its beautiful national parks from such military installations, and working with various national and international civil society partners to widen the parameters of preservation for its beautiful mountain heritage. Many NGOs have been active in the area, particularly as the recent conflicts have subsided - so many indeed that some schools are peppered with mulitple and competing placards of various donors.

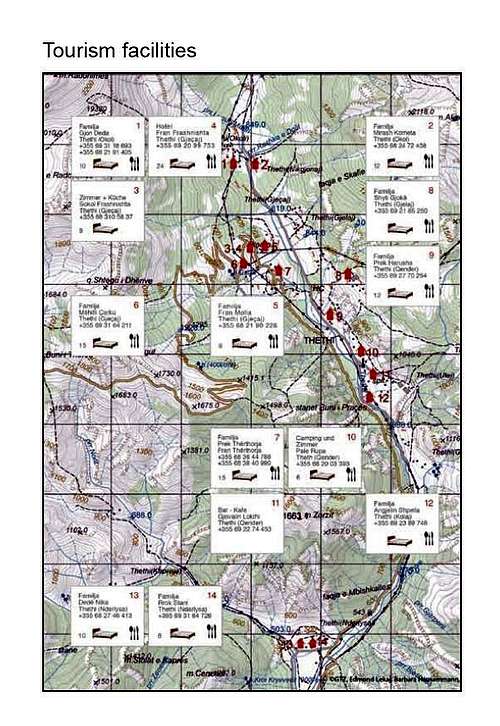

Certainly from a mountaineering perspective, one of the most noteworthy has been the work of the German Society for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) in both the the Theth area of Albania and the Gusinje area of Montenegro(see links below). But perhaps the most intriquing project in this regard is the idea of a Balkans Peace Park modeled on the idea of a Multinational Park like the Waterton/Glacier Park system straddling the border between Alberta in Canada and the Montana in the United States in western North America. This would attempt to integrate in a much larger scope the already existing national parks of the Accursed Mountains, the Valbona and the Theth in Albania, with the equally beautiful mountain regions of Plav-Gusinje area in Montenegro and Decani-Belaje area in Kosovo. This latter, indeed, includes the northern part of the Accursed Mountains. The summit of Mt. Gjeravica or Deravica, at 2656m, is the third highest peak in this part Dinaric range - next to Jezerce in nearby Albania, resting alongside Mt. Marijas (2530m), Maje Rops (2501m) and Mt. Koprivnik (2460m). In this project, the non-governmental organization (NGO)Balkan Peace Park Project has been working together with groups like the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), the SOROs Foundation, and various incipient local ngos such as Action Group Environmental Responsibility in Valbona and the HRID Mountaineering Sports Club in Plav, Montenegro, to help develop and realize this idea – with the collaboration of a host of other organizations both local and international including the UIAA and the World Conservation Union. Originally started by a group in the United Kingdom, the Balkan Peace Park Project has been gaining more traction, sponsoring annual gatherings in the mountain town of Theth, acquiring the sponsorship of Members of the European Parliament, and serving even as the inspiration for some of the first major climbing routes in the Accursed Mountains, such as the seven pitch ‘Balkans Peace Park’ route (UIAA VII- A0/AF) up Mt. Lagojvet by a team of SummitPost members, the first ascent of this 5th class peak in August 2009.The original idea of a Peace Park came from Morokulian Park between Norway and Sweden in 1914, at a time of great tension between those countries. A permanent monument to peace was built and inaugurated in the same year.Those interested in enjoying the Accursed Mountains in support of the Peace Park initiative should visit the Peace Park web page link above and consider joining in the annual July-August summer program in Theth.

II. Traveling and Staying in Albania

Touring Albania: The Last True Adventure in Continental Europe

Much of the experience in Albania results from the rugged natural and social surroundings. After fifty years of ultra-totalitarian rule, Albania has emerged from revolution, upheaval, economic collapse, ethnic warfare, banditry, black marketeering, and refugee crises to become an increasingly stable and economically viable, while nonetheless continually interesting and uniquely adventurous, part of Europe. It now has a vital press, a growing economy, a somewhat exuberant party system of two party government and opposition, but with a modern and progressive proportional system. To be sure, this is composed of a center-right 'Democratic Party' which has emerged from ponzi schemes to just be Berlusconiesque and an ex-Communist Party which is full of interesting intellectuals and now looks like a run-of-the-mill albeit shady east European variant of Social Democracy. But all of this is quite striking is a majority (Sunni) Muslim country with significant Catholic and Orthodox minorities, and a strong Bektashi influence. (The Bektashi are a Sufi branch of Islam which in Albania actually established itself separately and were recognized ever after as a distinct Islamic sect rather than a branch of Sunni Islam, as are most other Sufi orders.) Historically, amongst the mixed cemetaries of Muslim and Christian deceased appears as well the gravestones of the Bogomils, ancestors of the Cathari who stirred up the violent genocidal reaction of the Catholic Church in Crusader era France, but who continued on in relative peace in mountainous Albania.

Most notably, in contrast to much of the rest of the Balkans, Albania has spent so much time as a nation coming to terms with its own totalitarian past that it has felt little need to externalize its difficulties on other oppositional religious-ethnic divides, in striking contrast to the countries surrounding it. In contrast to the Islamic character of the connservative politcal parties and nationalist identity of Bosnia-Herzegovina or Kosovo, or even Erdogan's policies in Turkey, the conservative 'Democratic Party' and its sclerotic leadership reminds one of Berlusconi with lots of ritalin added in; and the sub-currents of a pre-modern blood feud tradition negatively affect the evolving legal-constitutional state surprisinly little. A sober observer might view Albania, of all the nations in the world with majority Islamic populations, as the one having the strongest institutions of representative government, in a country with near Malaysian standards of ethnic and religious diversity. Albania's mountains are sparsely but thoroughly populated due to the policies of the old regime - which privileged the wierd idea of an industrial-military mountain redoubt; as a result terraces of underproductive agricultural land are ubiquitous, shepherds can be found at work around nearly every precipice and gorge cut, and there are many aquaducts and other industrial cuttings that break up the climbing environment. At the same time, there is no one else much to bother the car-camping visitor who comes prepared for rough conditions, brings a four-wheel drive vehicle, and takes the necessary precautions against theft. (One possible hazard are wild dogs, which can be found roaming in packs from just outside the capital city to the highlands and ridges of some of the most inaccessible peaks. In most cases, simply circumnavigating their locations at a very safe and prudent distance seems to solve the problem, though I must admit that while doing so on occasion, I was happy to be carrying my ice ax just in case.) The roads are treacherous and winding, and in nearly all cases strongly imply 4-wheel drive. In many places, arrangements should be made to park cars during the day and at night. In some, a local guide or informant is still quite recommended. Generally, an expense of ca. 100-250 New Lek or a few Euros per night for ‘protection’ of vehicle or more for ‘camping fees’ can be expected. Since property relations are still not clarified and since there is a tradition of xenophobia as well as a highly developed host-guest culture in the Albanian highlands, it is best to exercise caution. When in doubt, having local connections via a guide or a property owner with ‘bed & breakfast’ arrangements or the like is recommended. Many towns have such helpful people, and they can frequently help manage a situation with family or friends in other parts of the mountains. Such arrangements grant one the nearly sacrosanct ‘guest’ status protecting one from the otherwise usual forms of banditry and highway robbery that are a well-known part of Albania highland history. Albania must be seen as the last true adventure left in continental Europe. The second poorest European state, it is terraced with tiny dirt roads, obscure and isolated mountain villages slowly draining of people, living on subsistence agriculture and remittances.

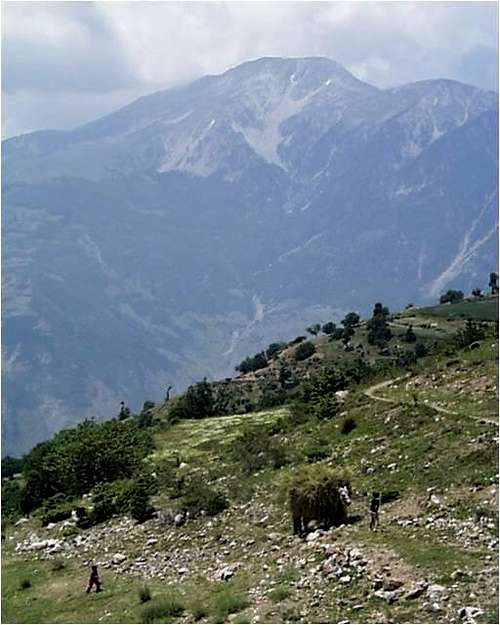

Rural life in north-east Albania - a moving haystack drawn by one school boy as another plays in the terraced fields, here nearly two hours gravel drive to Kukes, the nearest substantive mountain town. Orjost is right up against the Kosovo border; Mt. Gjallica rises in the background.

Rural life in north-east Albania - a moving haystack drawn by one school boy as another plays in the terraced fields, here nearly two hours gravel drive to Kukes, the nearest substantive mountain town. Orjost is right up against the Kosovo border; Mt. Gjallica rises in the background.It still contains active bands with assault rifles and purloined Daimlers from the EU countries. Even though much of the magazine stores were hawked to the Kosovo Liberation Army in 1997, this or that farmer might still be willing to show you their cache. But like Europe in general, guns are actually illegal, so Albania is assuredly not Texas. (The vehicular situation, on the other hand, is becoming greyer, but still colorful. Indeed, nearly all the vehicles in Albania in the years after the end of the old regime were Daimler sedans - providing Albania with a private automobile fleet subsidized by the German Automobile Insurance Fees and profit-oriented Italian customs officers. My favorite example was a Daimler mini-bus which still proudly and informatively retained the bumpersticker of a 'Snow Shoe Club' from a small township in German Lower Saxony.) Old tribal-influenced ways of life continue, especially in rural areas, amidst a largely Muslim population - though especially in the north west spreading out from Shkodra, in the area Edith Durham documented, there is still a significant Catholic population reaching up into the highlands. In some areas of the north, the tradition of the ‘blood feud’ is still quite active, and most of the inhabitants get by via subsistence farming, herding and remittances from family members working abroad.

A Kulla in Dragobi - traditional dwelling in this wild part of the north where the blood feud is still active, and where square fortified defensive dwellings can provide security for male family members caught up in legal vengance of the feud that can go through generations.

A Kulla in Dragobi - traditional dwelling in this wild part of the north where the blood feud is still active, and where square fortified defensive dwellings can provide security for male family members caught up in legal vengance of the feud that can go through generations.Albania politically and culturally is somewhat the opposite of Italy; its north is more conservative and poorer while the south, with historical ties to Greece, is where key early nationalist intellectuals came from, where the Communist Party developed most strongly, and from where the institutions of modernization, including the predominance of Tosk elements in the dialects, were most strongly felt and influential across the country.

The diverse religious and cultural traditions, indeed the mix of the unique Albanian language with its obscure phonetic system and the proliferation of traditions from Roman law and Latinate/Romanian words of a very old character mixing in the Kanun of Lek through to a variety of 'Albanianized' Turkish and Slavic expressions provides a polyverse linguistic and cultural background. Most of this adds color and spice to a vacation without involving any serious dangers or hassles. Serious crime is hardly a problem, as long as precautions are taken to protect vehicle and camping gear. With proper graces on the part of the traveler, Albanians in the mountains are typically as polite to visitors as they are proud of their own local and national traditions.Roadmaps are frequently unreliable, signposts poor to non-existent, and thoroughfare turns-offs or lack thereof obscure or disingenuously uninviting. The geography is distinctive enough, however, that one is usually well oriented after a day or two in any one locale; a short question of the many pedestrians using the roads or watching passers-by is usually enough to sort out a confusion.In many respects one is reminded of Latin America. In Albania, the state is frequently weak or ineffective in rural and remote areas; but as long as care and courteous arrangements with the local inhabitants are maintained, the ranges and wild alpine terrain in such areas are in their totality available to the visitor. Compared with the rest of Europe, Albania is a region free of rules and regulations. In contrast, for instance, to Montenegro and Macedonia, there is at present no 'permit' system from an 'interior' department regulating access. With regard to the northern mountains, criminality and smuggling were a problem after ca. 2001 only in the Bajram Curri area (Tropoje District), a part of Albania which for this reason perhaps may still require particular precaution if it is to be made part of a planned itinerary.Hotels are sparse and frequently unattractive dilapidations leftover from the totalitarian era, but are improving rapidly from the period 1996-1999, and tolerable accommodation is available in most areas with short drives of major crags. A 4x4 vehicle – rented or driven in – is preferable, but transport is also possible in the cheap, efficient and regular system of minibuses that criss-crosses the country, even on the most obscure and deserted mountain roads. Most of the main climbing destinations could in fact be reached by a sturdy VW or Renault with relatively high clearance, but such means will certainly slow down progress to and from trailheads and crag approaches. Many remote villages and destinations have farmers with extra buildings or primitive ‘bed & breakfast’ like accommodations. These are typically comfortable, interesting, and ‘authentic’, particular if one is served lamb together with the potent local form of rakjia or fruit brandy around the tin wood stove on a floor covered with sheepskins. Probably the best option is to arrange for long-term use of a legal four-wheel drive vehicle that could be driven into Albania via the ferry from Bari to Durres. Alternately, one could travel by highway via Zagreb-Belgrade-Pristina or Podgorica in Montenegro. Vehicles could be rented either in Montenegro or Kosovo, Macedonia or Greece, as long as arrangements were made to cross the border. One can fly into the capital of Tirana, or drive in through Montenegro to Shkodra, or through Macedonia or Kosovo into the north east to find the best rock climbing areas. Alternatively one could fly into Podgorica in Montenegro or Prishtina in Kosovo and rent a four-wheel drive for the short trip into Albania. It is also possible to drive easily in through Greece from Thessoloniki via Lake Prespa and/or Korce, but as most of the climbing is in the northern part of the country, this is probably less convienent unless one is already in Greece.Most of the excellent rock climbing is within a day trip of the towns of Tirana, Shkodra, or Kukes, with the exception of the Cem Gorge and Vermosh area, and the Theth-Valbona region. But be warned: distances do not appear great on maps, but become so over rutted, winding, unpaved mountain roads. If your headed to these regions and do not have prior arrangements for overnighting, be sure to bring your camping gear and sufficient food supplies, as there is no convienent 'Aldi' at the end of these long dirt road canyons. Bed & breakfast arrangements can, however, be made in these areas.For more detailed information on Albania, the ‘Blue Guide’ written by James Pettifer is strongly recommended. Though Pettifer is not a particular devotee of high mountain environments and alpinism so much as Albanian culture and traditions, he is one of the best English language historians of the country, and his guide is well written and provides a wealth of detail and generally reliable information. Road maps are readily available, and excellent topographical maps can be purchased from the Albanian Armed Services and the Geographic Institute for ca. 1500 Lek a piece (more for on-line versions) in varying sizes for all of the country; and they are recommended navigation tools. Free older topos of the entire country in 1:50,000 are available from the Univ. of Calif. at Berkeley and at the website Bunker Trails, as long as one can read Russian; these must be combined, however, with very good road maps as there are now many more roads, not to mention artificial bodies of water, than was the case during the 1940s-1970s. Also, the Russian maps have an annoying habit of 'extending' international borders in obscure areas in this or that direction according their their historic percieved geo-political interests. This generally on these maps seems to make the Albanian border extent bigger and those of the former Yugoslavia, especially along the Montenegrin border, smaller. Actually running into an angry non-Albanian border officer in these high mountain areas is extremely unlikely, but there are reports of left over unexploded ordinance - from the Greek civil war in the area of Mt. Gramoz, and the from the recent Balkan conflicts in the areas of Mt. Korabi and along the Albanian-Kosovo border. The Soviet era maps, however, follow a tradition of military cartography, which includes many civilian uses and thus provides much more detail than NATO variants on vegetation and other issues of interest to trekkers and climbers.

III. Tirana-Kruje Area Central Coastal Range

A. Kruje Town

==

Kruje Castle and the cliffs behind - where the war leader Skenderbeg held off the Ottomans in the 15th century. - photo Bethany Sanders

==

Kruje minaret

==

Kruje is a mountain town located at the northern end of the Kruje-Daiti Range of mountains on the western slope facing the Adriatic, complete with a famous castle and excellent views. Kruje Mountain (1150m) to the north is followed looking southwards successively by Mt. Gamtit (1268m), Mt. Bastarit (Berarit)(1403m), and Mt. Daiti (1612m), with steep limestone gorges cut into the ridgelines of the range between each peak, and limestone escarpments running along especially the seaward or western slopes of the range.

At Kruje, there is a gorge as well at the north end of town can be reached by the lower of the two roads that lead inland from the town; it is notable for its vertical keyhole shape cut into the limestone cliffs; and the characteristic long limestone ridge which climbs to the summit of the mountain north of Kruje Mountain. The lower Kruje road, the Rruga Burreli, can be followed to Burrel (though the main road to Burrel and Peshkopi is via the coast road and Mat river).

Just out of town, the road transverses several steep limestone faces just after leaving Kruje. The Kiktafe stream below, north of Kruje town, disappears here into a cavern in the limestone, and there is much carst surface with dolines. The upper road leads to the top of Kruje Mountain, and cuts through three successive limestone buttresses on the way up the mountain. A third road leads along the base of Kruje Mountain’s western side past a series of overhanging limestone bluffs and pinnacle formations to a new prison complex some three km South of Kruje Town. The formations along the road fine face climbing but would be difficult to protect, and difficult, steep and hard-to-protect limestone faces constitute the best part of the other climbable terrain around Kruje.

==

Mt. Kruje - The line up to the top limestone point on the right is a scramble with a spritely 3rd class section at the top. Steps down from Kruje mountain are found to the left.

==

B. The Coastal Range with Bovilla Gorge Between Mt. Daiti in the South and Mt. Gamtit in the North

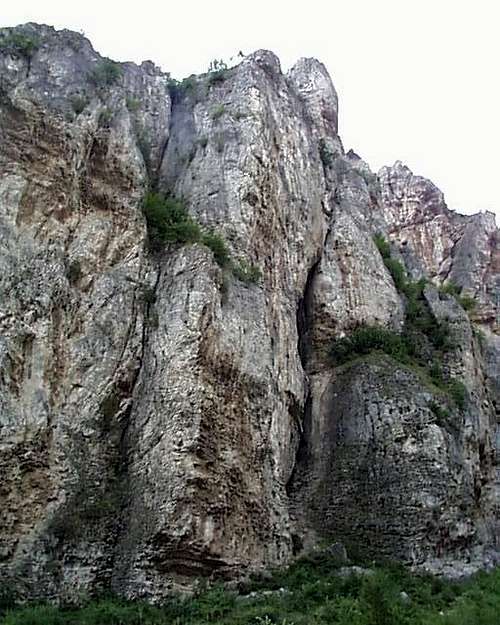

Entrance Area Bovilla Gorge between Tirana and Kruje contains the best rock climbing available in the greater Tirana area. It can be reached via a twenty minute trip down the road to Zall-Herr that turns right at the Bathore intersection one kilometer south of the town of Kamez (pronounced 'kam-ze') on the Lezhe-Shkodra Road. The badly rutted dirt road follows the Herr I Bastarit River past the Albanian Army Commando Base and a gravel pit. The road rises as the road cuts through the gorge on the north side after crossing a bridge at the entrance to the gorge and then rises, passing the Bovilla Dam. This dam holds the drinking water for the city of Tirana in the reservoir.The entrance to the gorge is marked on the south side a pair of distinctive limestone pinnacles in the front of a set of steep limestone crags. These rise in a series of archlike ridges up the front face of Mt. Bastarit (1403m) on the right and Mt. Gamtit (1268m) on the left.

==

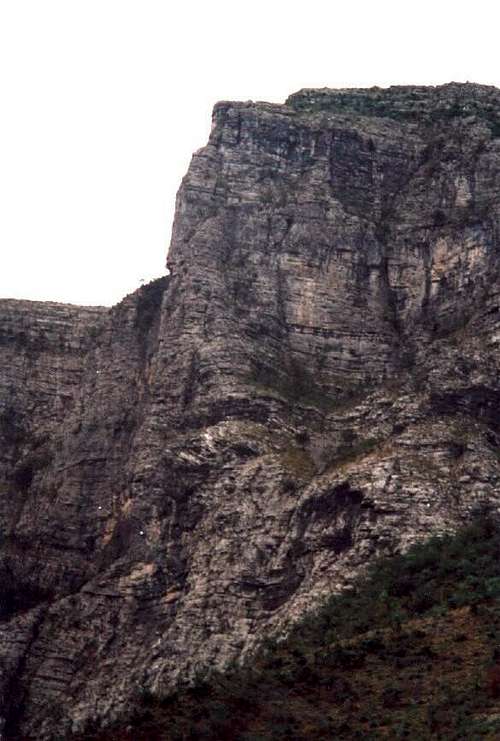

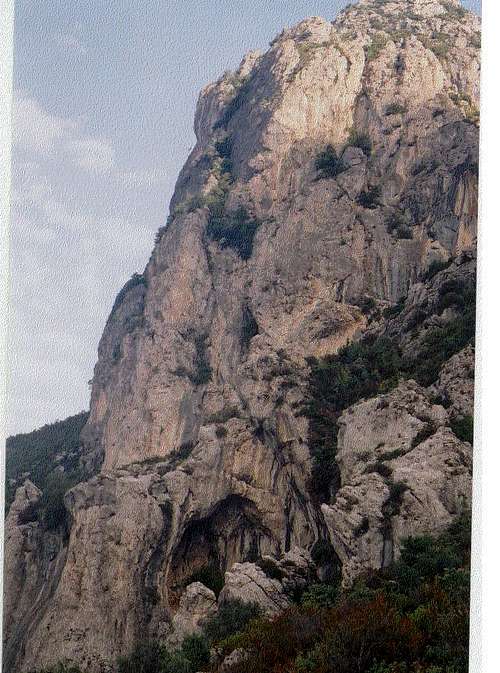

The northern shoulder of Mt. Bastarit runs up and south, viewed from the Western entrance to Bovilla Gorge.

==

Mt. Gamtit's Western Side

==

The Entrance to Bovilla Gorge from near the Albanian Commando Base. The three crags of Gamtit’s south shoulder appear on the left, the vertical faces of Bastarit’s north shoulder on the right, and the back ridge of Bastarit rising from Bovilla Dam visible in the center of the picture.

==

On the north side of the entrance, three crags rise up east side of Mt. Gamtit. The first crag – marked a large orange face rising above the road -- contains an easy fifth class ridge route that can be reached by vegetated fourth class ledges at the base of the large orange face. A third class ledge rises on the face to the left, dividing broken lower sections from the steep face capped with overhangs above. The second crag is to its left and can be reached through the gully on its right, which also provides descent from all three crags. Two major fifth class cracks, the left hand in a large north-facing corner, provide the most obvious of several lines. The third crag is the largest and can be reached by following the olive terraces stretching down towards the road. It offers steep free routes leading up the steep buttresses lying between overhanging sections; and three-four pitches of fourth and easy fifth class take one up the right hand ridgeline.

The third or left most of the Lower Gamtit Crags has the most interesting possibilities - hard lines starting left of the round cave area, and easier routes on the ridges to the left.

The third or left most of the Lower Gamtit Crags has the most interesting possibilities - hard lines starting left of the round cave area, and easier routes on the ridges to the left.

Bovilla Gorge – Dam Area The entire interior of the gorge is mottled with ridge systems and crags reaching down to the streambed. A couple of faces along the road can be top roped, while closer to the dam, longer problems rise up to the left, including a capstone crag about twenty minutes walk uphill from the road. A number of crags, including a fifteen meter pinnacle, are formed down southern sides of the gorge from broken carst formations ending in the area of the dam runoff.

Mt. Bastarit drops in two distinct ridges down directly onto the reservoir Dam. Both ridges offer good multi-pitch afternoons; the second can be reached by following the goat trail along the reservoir shore that begins just beyond the tunnel leading to the reservoir intake units.

Above the 3rd and largest of the Gamtit crags, there is more rock to climb on the way to Gamtit's summit.

Above the 3rd and largest of the Gamtit crags, there is more rock to climb on the way to Gamtit's summit.Mt. Gamtit – Backside or Eastfaces Beyond Bovilla Dam, the road turns left in a series of switchbacks up over the reservoir and along the backside of Mt. Gamtit, which contains three separate distinctive rock formations. (1) Gamtit Slabs: a small crumbling limestone ridge rising from the dam breaks off eventually into a series of steep limestone slabs, and eventually a series of high corners formed by the drainage funnels in the cliffs rising above the slabs.

Beyond the dam above the road limestone slabs appear, with some 5th class corners in the formations above them.

Beyond the dam above the road limestone slabs appear, with some 5th class corners in the formations above them.

Gamtit Back Side Slabs - with a Fine Corner to Climb at around 5.10 done by Maria Rodin and Brian Robinson

Gamtit Back Side Slabs - with a Fine Corner to Climb at around 5.10 done by Maria Rodin and Brian Robinson

(2) Gamtit Back Crag: A limestone crag rises some 350 meters high to two points on the same ridge line 1.5 km further up the road above a parking lot formed by an abandoned factory, providing several multi-pitch fifth class lines. - no development in this area yet.

Beyond the slab area, the east side of Mt. Gamtit contains a main crag, broken in the center by a 4th class fissure, but with harder lines, especially on its northern face.

Beyond the slab area, the east side of Mt. Gamtit contains a main crag, broken in the center by a 4th class fissure, but with harder lines, especially on its northern face.

(3) Gamtit Back Ridge: A large and broken ridge of limestone reaches down from Mt. Gamtit towards the east three km north of the reservoir.

C. Mount Daiti and Babru Gorge Up the Tirana River to Brar

Mt. Daiti (1612m) rises directly east of the Tirana metropolitan area. Traces of pre-historic settlements have been found on its highlands, and the most common theory is that the name derives from the Greek mountain nymphe Diktynna. A road leads to a National Park on the summit, from which a number of crags can be reached. (Since 2005, a gondola has been put in place, which offers a good perspective of the main climbing potential to the left as one goes up.)

==

Mt. Daiti viewed from its new gondola. The main cliffs for rockclimbing can be seen in the upper left.

==

While it is quite irritating to have military installations which thus prohibit climbing to the summit, this does not affect the rock climbing, which is on cliffs below and to the left of the Fushe e Daiti or Daiti Meadows where the gondola ends and the restaurants are found. Others can be found by turning left of the road up Mt. Daiti on the Rruga Dibres that passes the hamlet of Babru before entering a limestone gorge separating Daiti from Bastarit.

==

Mt. Daiti Upper Cliffs - down and right several hundred meters from the Summit Restaurants - Lamb and Raki after some very steep rocks

==

A series of ridges run from the entrance of this gorge up the side of Mt. Daiti, in which a pair of easy fifth class ridge routes can be followed. Alternately, approaches by foot are available to the steep palisades of vertical and overhanging limestone ringing the northwest sides of Mt. Daiti. The central buttresses - lower angle in character - that lie underneath the summit can be reached from an access road a few hundred meters beyond the Chateau Linze complex on the Mt. Daiti road.The road which goes straight when the left turn leads up to the park and military installations at the top of Mt. Daiti tranverses the southern shoulder of Daiti and leads back through shattered serpentine highlands to the Malesi me Gropa, or 'Mountains of Holes', named such due to the huge number of dolines which are found in the region. It was here that the Hoxha partisans and the British SOE had their nearest outposts to the capital city during the period of World War II German occupation. Despite being close to the capital, within a few kilometers past Daiti this region becomes very obscure.

D. Erzenit Gorge

Erzenit River Gorge and Cave South of Tirana on the Rruga Elbasanit, a left hand turn at a large white stone adjacent to a long concrete aquaduct some 15km from the city center leads uphill along the southern bank of the Erzenit River. The large escarpments to the right forming into the Erzenit North and South Cliffs in the gorge formed by the river are visible from the Elbasan Road. Follow the road up to the village of Pellumbas, on the south hillside of the Erzenit Gorge, where one can park.Follow the distinctive goat trail up to the large limestone cave and 60-150 meter cliffs on the south side; or alternatively walk down and follow the aquaduct - including through the tunnels of running water - on the other, northern side of the gorge up through it to the reservoir at its mouth - a striking view of the dolines and river below.

Erzenit Gorge Entrance. The picture illustrates the line of cliffs rising on both the North and South Side of the Erzenit Gorge, with dam and reservoir behind the last set of visible cliffs — the North Cliffs -- rising to the left. Pellumbas Butte is formed by the ridge rising to the right.

Erzenit Gorge Entrance. The picture illustrates the line of cliffs rising on both the North and South Side of the Erzenit Gorge, with dam and reservoir behind the last set of visible cliffs — the North Cliffs -- rising to the left. Pellumbas Butte is formed by the ridge rising to the right.The river flows through a series of deeply cut waterfalls that provide climbing opportunities, as does the large limestone cliffs that rise from the gorge cut up the mountain to the north and south.

South of the Erzenit River cut, a series of steeper and overhanging cliffs rise to a long rocky capstone of a large butte of limestone rising for a kilometre above the hamlet of Pellumbas and dropping down to the south into the town of Krrabe and the path of the Murdhardit River. Accessible either directly up the path from Pellumbas or up the steep scree pile from the Erzenit gorge cut just below the dam, one can see the entrance to a large, 100m deep limestone cave with striking stalagtites and stalagmites, and some steep and difficult climbing lines on these Erzenit South Cliffs in the limestone faces just uphill from the cave entrance.

Erzenit - Upper South Bluffs - the cave entrance is in the lower left of the central band of cliffs.

Erzenit - Upper South Bluffs - the cave entrance is in the lower left of the central band of cliffs.Just before the turnoff to the village of Pellumbas, the road turns right and south up to this headland, cutting after a few switchbacks through the southern escarpments of Pellumbas Butte overlooking Krabbe. This series of the Krabbe Escarpments offer some climbing possibilities, though much of this portion along the road cut is of broken and uneven quality. The main set of cliffs leads below the road where the road itself cuts across the escarpments near the top of the Pellumbas Headland.

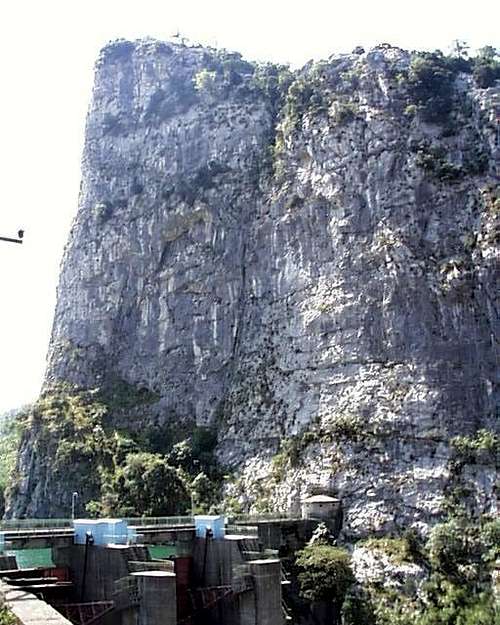

E. Shkopet Reservoir Rocks and Mat River Gorge

About six kilometers up the Mat River from the point where the Mat flows into the Fan, a large hydroelectric dam contains the smaller and lower of two Reservoirs at Shkopet - at the point where the Mat River gorge is cut into two rocks, North and South Shkopet Rocks. The area is roughly 1.5 hr. drive from downtown Tirana, and 20 minutes down the road from Burrel.

Below the Shkopet rocks in the gorge canyon of the Mat are a series of crack-lined cliffs, while rising above this complex to the north rise the Dervent Ridges and to the south the Mount Mallezit (1113m). Especially the Dam Cracks in the reservoir canyon and the North and South Shkopet Rocks offer spectacular and completely unexplored climbing possibilities.

IV. Mirdita Highlands

Mirdita Mirdita is a famous area in Albania due to its historical role in clan dominance and blood feuds, and serves as the locus for Nobel Prize winning author Ismail Kadare's most esteemed novel, Broken April. It is now a real backwater, rapidly loosing its population to the urbanizing areas on the coast, filled with endless forests, and traversed by the Fan River. A few crags in the middle of nowhere and an adventurous camping trip are what is to be found, not a plethora of opportunities. The series of crags in the Mirdita area can be accessed via the main road between Tirana/Lezhe and Fierza/Kukes. After driving past a series of broken composite crags ca. 10 km after leaving the town of Rreshen, a road turns right down into the Fan (I Vogel) River valley at Blinisht just beyond the police station perched on the scenic overlook. As one descends this ‘improved road’ leading to an abandoned copper mine at Reps visible in the distance, the river valley below and the crags in the area can both be clearly viewed as long as the sky is not overcast.

Two secondary dirt roads traverse Mirdita: i) one north-east along the Fan i Vogel from Reps through the village of Klos and ending eventually on the primary Puke-Kukes road near the village of Kalimash, and ii) another parallel north-eastern path through the Orosh highlands, past the hamlet of Bulshar and up the sides of Mt. Gurit te Cikut (1413m) and Mt. Gurit te Kuq (1511m) along the Shenjtit moutain ridgeline. The pine forested mountain terrain is highlighted by the reddish color of the earth, giving this area of Mirdita in the Fan River drainage its characteristic aspect. A large scree field scoring the mountainsides directly behind a large complex of abandoned copper mines indicates a gorge cut in the Fan revealing excellent crags rising out of the riverbed.

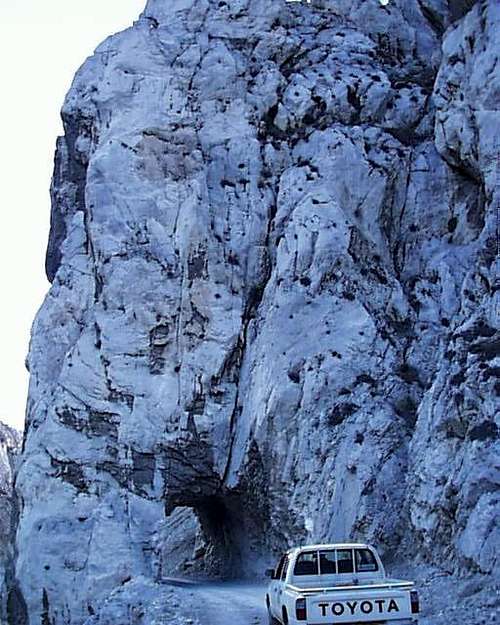

A large pillar of limestone cuts through the southern side of the Fan i Vogel river 3 km upstream from the village of Klos.

A large pillar of limestone cuts through the southern side of the Fan i Vogel river 3 km upstream from the village of Klos.Looking up and to the right, a series of limestone cliffs rise on the plateau above. The former can be access by driving up the Fan River past the abandoned copper mine in the direction of the village of Klos. The latter are accessed on the more difficult but spectacular mountain road that leads right up two km upstream from the abandoned copper mine.

Following on the southern side of a steep streambed opposite the village of Gryke-Orosh, the road continues past logging operations upwards, eventually running along the base of a long terrace of limestone crags forming the Mal e Gurit de Cikut area. After the series of ca. 40-60 meter crags uplifting in a series of jagged rows above the road, a long cockscomb crag rising above a couple of farmhouses offers additional cragging in this upper area. Both areas provide local camping opportunities and are ca. 4 hours by vehicle from central Tirana.

==

Beyond the pedestal crags of Mt. Gurit te Cikut, the Shenjtit highland road passes this limestone cockscomb of the formation (Cikut = 'rim' or 'edge') - average 35 m high and rising as one travels the Orosh logging road north past Male Gurit te Cikut.Shenjtit Highlands - Above the Reps abandoned copper mine runs the Shenjtit Highlands road past the two visible ridge formations of Mt. Gurit te Cikut and Mt. Gurit te Kuq. Down to the left runs the Fan i Vogel valley.

==

Limestone crags on the high road south of the Fan river valley through forested and isolated Mirdita. A row of such crags forms the pedestal terraces of the Mt. Gurit te Cikut rising above the Fan river beyond the villages of Gryke-Orosh and Bulshar. This crag are part of a long escarpment visible from the main road to Kukes which are serviced along their entirety by a logging road.

==

Trip Report of Kayak Trip down the Fan i Vogel

For a trip report (in Italian) kayaking the Fan i Vogel River in this area, see Anna Ferrari at 'architetura di pietra'.Beyond the Gurit te Cikut formations, a left turn down the mountain brings one to Klos in the Fan River valley. A complex 52 km road leads to the main road to Kukes along the base of Mt. Zebe (1987) and then east over a pass just south of Mt. Kacinarit in the depths of a forested region, albeit with limestone ridge lines and escarpments running of the sides of Mt. Zebe.

Remark on Unknown Large Rock Formation Visible from Mirdita

The main road to Kukes and the north-east continues to wind along the shattered composite ridge line to north of the Fan. From this road, on occasion, across the valleys of Mirdita to the south west one can see an apparently huge buttress-like steep formation facing north - think of the forehead and cap of a Gulliver lying on the ground from north to south. However, this formation does not come into view on any of the Mirdita highland roads, or indeed from the Drin Valley between Kukes and Peshkopi, though it would appear to ly nearest to the Drin north of Peshkopi but unaccessibly in neighboring Mirdita. Perhaps only a vast piece of dirt or shale, it is certainly intriquing from a rock climber's point of view.

V. Mountains to Climb in Southern Albania - South of the Shkumbin River

This text focuses for the most part on the north of Albania, thus the 'southern' Dinaric Alps, especially around the Tirana capital region and the North East. As a rule, alpine and rock climbing potential are found north of the Shkumbin River - which transverses Albania from the Bay of Karavastase to Lake Ohrid along the lines of the old Roman via egnatia and divides the language dialect distinct Gheg north from the Tosk south. However, while the mountains in the south are lower, more composed of serpentine, sandstone, and tufa, and contain less of the characteristic Dinaric limestone, they still merit interest. This section looks at several of the more interesting mountains and the hiking and climbing potential they offer in the south of the country.

Climbing Mt. Tomorri (Mt. Partisan) in the Mali i Tommorrit

Mt. Tommori (2414m), renamed Mt. Partisan during the years of Hoxha's state socialism, is a large and marked feature in the center of Albania, and as a symbolic central mountain redoubt in a state founded on a kind of mountaineer Marxism-Leninism or Maoism, became the first 'national park' of Albania, near the beautiful museum town of Berat, and lying below the huge one time top-secret munitions production town of Polican on the road south of Berat.

The Tommorrit Range as viewed from just south of the town of Gramsh

On a clear day, Tommori, the highest and most northern point of a long and beautiful though not particularly steep ridge line, can be seen as far away as the city of Elbasan, and is also clearly visible from Gramsh, from Berat, and from the valleys surrounding it.Access to the TrailheadDriving south out of museum town of Berat, take a sharp right about five km out of town where the road crosses the Karkanjozit stream. The road follows the stream for about three km till the road leaves the stream bed and begins to rise. Continue to follow the bad four wheel drive road up the mountain side for another seven km until it crosses another stream bed and makes seven marked switchbacks immediately after this crossing. Stop at the end of the last switchback while one can still see the stream bed and park.

The Tommorit Range viewed from the town of Berat, with Mt. Tommor or Partisan on the left side.

The Tommorit Range viewed from the town of Berat, with Mt. Tommor or Partisan on the left side.

To the SummitThe stream bed, or the trail just to its north, can be followed to the point where it allows one to access the broad shoulders of Tommorit that rise above the southern most of the two great canyon-gullies that divide the mountain in a north south direction up its sides viewed from the north as it is seen from towns of Elbasan or Gramsh. Continue up but contouring to the south to avoid going down into this canyon until one reaches the summit.

Climbing Mt. Kendervices in the Griba Range

Mt. Kedervices (2121m) is located in the Griba Range of Albania that divides the Vjose River valley flowing north from Tepelene with the coast, part of the same long ridge line that further south forms the Mali i Gjere peaks on the western side above Gjirokaster.

Access to the Trailhead To reach the trailhead, drive south east out of Tepelene, a town known for its bottled water springs and its castle home of the famous ‘Ali Pasha’ about seven km to the village of Bence. Continue eleven km further to the village of Pregonat, keeping straight there and avoiding a possible right turn. Pass through the village of Gusmar, and then, 32 km out of Tepelene, the village of Nivic. After Nivic, four wheel drive is required. Turn left there at the main square and stay left aft a fork one km further. The trail head is 5km further, 39 km from Tepelene. [Mujo Gjoni runs a small restaurant in Nivic and welcomes hikers in the future. He is willing for a small price to look after vehicles and can help with services and support in the village. Phone: +355 (0)682951906]

To the Summit From the trailhead follow the trail towards the mountain, passing a rock with a memorial inscription and then heading up a small valley curving to the right. Here you can leave the trail and ascend directly up the slope above, eventually traversing (second class) a band of cliffs broken into natural steps via a shallow but distinct gully or by following easier terrain to the right. A broad summit ridge follows leading thro three humps, each marked by cairns with the eastern most cairn being the highest point. It takes 2-3 hours to reach the summits from the trailhead.

Climbing Mt. Valamara in the Valimares Range

Maja e Valamara (2373m) is a bare topped and rounded peak in the Valemare mountains separating the Devollit River valley and the town of Gramsh on its western flanks from the Skumbin River and Lake Ohrid watersheds to the east.Driving to the TrailheadA first class walk up, Mt. Valamara is best climbed from the hamlet of Grabova, with its isolated hotel. Grabova can be reached by road from the town of Gramsh by driving south and turning left off the main road after about 16km at the village of Bulcar. It is roughly 26 km further on a four-wheel drive dirt and gravel road to the lodge at Grabova, which appears soon after a dramatic limestone cut in the otherwise rounded surrounding features, some two hours drive from Gramsh.To the SummitFrom the hotel at Grabova, follow the good trail up the valley to the east along the left side of the river.

After about an hour’s walk the trail cuts back and up to the left to a small valley which in turn leads to the summit ridge. The summit is about two hours walk from the hotel at Grabova.

Note: the route descriptions and photography of Valamara and Kendervices are from Petter Bjorstad descriptions on his interesting websiteand have been used gratefully with his permission.

Mt. Valamara as it is seen rising behind the Grabova Hotel. Photo courtesy Petter Bjorstad.

Mt. Valamara as it is seen rising behind the Grabova Hotel. Photo courtesy Petter Bjorstad.

Climbing Mt. Papingut in the Nemercka Range

==

Maja e Papingut (2185m)is the highest peak in the Nemercke ridge line of mountains which rise south of the town of Permet along the Vjose River. - Kolonje District - photo: Milan/Galeria Shqiptare

==

The Mali Nemercka Range is an extension southwards of the Mali Dhembel Range and Mt. Papingut, at 2185 meters, is the highest point of this striking ridge line.

Both are part of the same ridgeline above the Vjoses river to the south-west as one drives from Kelcryre to Leskovik. They mark a really magificent formation including faces on Papingut of striking steepness, but like much of the geography in this area, of questionable quality rock from the point of view of climbing.

Driving to the Trailhead Drive south east on the road from Permet to Leskovik eight km to the intersection of Vjsose River with Lengatices River at Petran. Roughly eleven km farther at a bend in the river, a sharp right turn off the road leads to a bridge crossing the river and providing access to the villages of Pellumbar and Strmebc on the other side.

To the SummitThe road peters out near Strembcec but a distinct goat path leads up into the moraine at the base of Nemercka/Drities/Papingut. From the moraine, a variety of 3rd, 4th and even 5th class paths to the top are possible.

VI. Kukes to Peshkopi Area - North East Albania

Sketch of the Kukes Area/NorthEast Albania

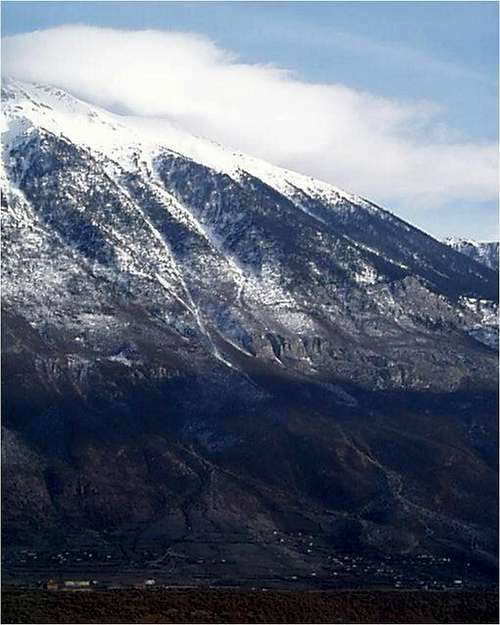

Kukes became famous during the 1999 Kosovo refugee crisis as one of the two main border crossings out of Kosovo over which the Serbian military forces pushed their campaign of ‘ethnic cleansing.’ (Indeed, it is still the only town to have been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for it efforts in accepting refugees during the Kosovo crisis.) Besides a beautiful alpine environment, the town of Kukes has little to recommend for itself. But it is located within a short drive of several large masses of limestone in sharp gorges, as well as the alpine peaks of the western frontier range separating Albania from Kosovo and Macedonia. This range runs from Mt. Koritnik (2394 m) on the border with Kosovo and neighboring Mt. Gjallica (2486 m) – both strikingly visible from Kukes Town – south to Mt. Kolosjan and Mt. Kasllabkut (2173m), where the highlands, in the Shishtavec plateau, meet the border with Macedonia. The peaks then run due south along this border to the Mt. Korabi group. This divide includes a row of high summits and false summits bi-secting the border, running through the Mt. Korabi group(2751 m) - whose main peak tip also bisects the countries and is the highest in both Albania (Maje e Korabit) and Macedonia (Golem Korab) - due south to Mt. Velivaret (2374m), with the town of Peshkopi nestled in its foothills. The Korabi group lies on the frontiers of Albania, Kosovo and Macedonia, with the the Palaeozoic rocks of the Macedonian Sar Planina mountains and highlands (themselves rising to 2500 m) dividing Kosovo from Macedonia also running north and east from the same highland point. The Sar Planina range -- massive, strongly folded and independent of the Drin Valley structures -- likewise offers few technical opportunities, though fabulously beautiful highlands for treking and traveling.

The Goran Village of Shishtavec in Winter - an highland town just in the Northern border of Albania at the edge of the extensive Sar Planina alpine meadowlands

The Goran Village of Shishtavec in Winter - an highland town just in the Northern border of Albania at the edge of the extensive Sar Planina alpine meadowlandsThe peaks south of Korabi located in Diber District around Peshkopi offer less in the way of technical climbing, with the exception of a small but interesting gorge near the trout farm of Arrez between Peshkopi and Kukes. Korabi itself, located at end of a canyon leading upwards from the village of Radomir, is a striking setting, and offers much rock climbing potential on its Albanian side. The Black Drin Canyon south of Kukes on the road to Peshkopi, however, is wild and interesting for those with four-wheel drive. Those portions of this canyon in Kukes District offer more rock climbing possibilities. From the villages of Skavice, Resk, Kolosjan, and Bushtrice, spectacular mountain scenery of the bare rocky uplands and numerous limestone crags characterize the landscape. Beyond this area, the main climbing is in two gorges draping the sides of Mt. Gjallica formed by the Lumes River on its northern and the Tershanes Creek on its southern shoulder. For scenic views, the small hillside mountain villages on the eastern sides of Mt. Gjallica and Mt. Koritnik and the highland regions beyond are worth a visit - villages such as Brekje on the eastern side of Gjallica, Orjost on the eastern side of Mt. Koritnik near the border with Kosovo, and the mountain hamlets of Strez, composed of Lumes Albanians, or Shishtavec and Borje, composed of slavic speaking Muslims known as Gorans. Some nine villages on the Albanian and twenty-two villages on the Kosovo side of the border are entirely or in majority constituted such ethnic Gorans.

While there is some question as to whether this slav heritage is Macedonian or Serbian, since the dialect of Goran is an evident mixture of both language variations, the Gorans are in socio-political terms, like the Muslim slavs or 'Bosniaks' in Bosnia, or the Muslim inhabitants of the Serbian ‘Sandzak’ between Montenegro and Kosovo, ethnically and linguistically Slavic and thus ‘nationally’ different from Albanians; and yet as Muslims frequently understood to be radically different from Orthodox slavs like the Serbs or Catholic slavs like the Croats.

The Village of Cernelev (* topo 3) is visible on the hillsides east of the eastern side of Mt. Koritnik. Terraced agricultural land lies below down to the Lumes river, and grazing meadows reach above the village. A close look at the north slope in the lower right shows the only road to the village snow covered, and thus accessible only by foot or donkey.

The Village of Cernelev (* topo 3) is visible on the hillsides east of the eastern side of Mt. Koritnik. Terraced agricultural land lies below down to the Lumes river, and grazing meadows reach above the village. A close look at the north slope in the lower right shows the only road to the village snow covered, and thus accessible only by foot or donkey.There is no great social or political divisions or tensions which characterize Goran-Luman or Goran-Albanian relations (as in contrast for instance is the case south in Himare among Greek speaking minorities), but in the various conflicts over identity and ethnicity, the Muslim slav enclaves like those of the Gorans or in the Sandzak or in Bosnia proper frequently have divided and mixed loyalties depending on the historic circumstances of rule and subjecthood.

Mt. Koritnik - eastern side looking from the village of Kollovoz - the Albanian side is to the left; on its right side the shoulder descends into Kosovo (Photo - Jonaz Kola)