|

|

Mountain/Rock |

|---|---|

|

|

42.43765°N / 19.75616°E |

|

|

Shkodra |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Trad Climbing |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall |

|

|

7274 ft / 2217 m |

|

|

Overview

Mount Arapit, in Albanian Maje e Arapit or sometimes Maja e Harapit, is one of the most striking mountains in that part of the Albanian Alps known as the ‘Accursed Mountains’, Bjeshkët e Namuna in Albanian or Prokletje in Serbo-Croat, a range which sweeps across three countries including northern Albania, southern Montenegro, and south-western Kosovo. Though only 2217 meters high, it forms the dead end of the beautiful steep glacial valley of Theth National Park. ‘Arapit‘ is presumably related to ‘Arab‘, and means colloquially the ‘moor‘, the ‘dark‘ or ‘swarthy‘ one. This expression doubtlessly reflects the strong cultural distances between especially these northern tribal areas, historically Catholic, and the Ottoman rulers who more or less claimed control up until the early 20th century, as arapash means ‘harshly or ‘thoughtlessly‘, and the expression ‘U be lesh arapi or‘ translates roughly as ‘everything is topsy-turvy.‘ But the expression also seems fitting for this gigantic monolith and its gaping 800 meter vertical limestone face of banded and darkened streaks of limestone caused by the remarkable sections of extruded iron which scar its dark smooth looking and ominous face.

Arapit looks down over the valley of sweeping limestone ridge lines of the massif formed by Mt. Radohimes (2568m) to the West and Mt. Jezerca (2692m)to the East as the valley formed by the Shala River descends sharply to the south. Arapit's south facing wall forms a continuous formation of banded limestone sealing in the entire valley – where its western shoulder guards the famous Qafa e Pejës or ’Peja Pass‘ (1705m). Left: The first view of Mt. Arapit as one comes over the Thore Pass from Boge: wrapped in the mists, and with the spectacular, often unnamed and even more UNCLIMBED towers behind and leading north to Montenegro.

Though sometimes called the ‘Matterhorn‘ of Albania because its sharply pointed summit and its imposing and spectacular south face cutting like a huge tombstone across the top of the dead end valley, Arapit is not a fourth class peak. A winding and confused but not difficult third class ascent leads from the Peja Pass up through the carst formations and very steep meadows of its eastern shoulder. However, on all other sides, steep buttress of limestone drop down from the summit, making every other face a serious fifth class endeavor. Up to now, very little climbing has been done on this peak, though there are nine known routes: three on the main south face or the 'Valley Side', and five on shorter and rounded faces, ridges and pillars of the western, north-western, and northern sides. The steep faces and corners of the eastern end of the shortened ca. 500m South Face rising to the main summit are unclimbed, as are - with few exceptions - the buttresses and faces of the western and northern sides, which average in length between 200 and 400 meters in climbable length.

This picture to the left shows the 3rd class walk up from Peja Pass shows the fascinating looking slabs rising up the north-eastern buttress of Arapit. From the north face in the skyline all the way 'round to the South Face, Arapit is a cornucopia of 6-8 pitch undone routes on extremely high quality sometimes smooth and sometimes featured carst and limestone. The easiest route up follows the meadows left and then follows the left hand skyline.

These bands form, geologically speaking, three distinct epochs; and thus climbing the South Face one manages, as the Albanian Geology Professor and longtime member of the Partisan Alpinism Section, Kujtim Onuzi has noted, first a passage through the Triassic areas, which are slightly lower angle and highly striated into parallels. There is a distinctive fracture at this point, and the rock above changes markedly, giving one a vivid experience of the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event as one goes by, and thence in the steeper Jurassic levels, the top most of which are very steep and mottled with a band of extruded iron ore marvelous to climb upon. Above this band, the upper sections of the face are marked by Ureides, and in typical limestone fashion are both more compact and less striated and also at the topmost sections more slabby and featured as a result of the stronger weathering processes of wind and water on the soluble limestone. The rock quality is quite good, probably on an average better than is the case with the great limestone walls of the Dolomites for example, though the absence of climbers in this area means care must be taken with loose blocks. In regards to ‘kitchen appliances‘, these are generally of the size of ‘toasters‘ and ‘microwaves‘ with the very occasional ‘stove tops‘ and(smallish)‘refrigerators‘, generally well placed and resting in the parallels, but occasionally and especially in the upper regions, these can take the form of large and precarious items on the upper slabs and in the steep gullies. First ascent parties should therefore be careful, and be prepared for significant cleaning and ‘moving‘ activities. The relatively low elevation between one and two thousand meters above sea level and the south facing character of the wall means that there is much vegetation, especially grass, but also scrub oak, pine, and heather on the face despite its extraordinary steepness, and this must occasionally be gardened to expose stone good enough for climbing. From the base of the South Wall directly below the western shoulder, a steep gully of scree and talus rises sharply to the east, shortening the length of the face on this side and up to its higher eastern and true summit point in a series of spectacular buttresses. Following the path to this gully, and then moving left onto the steep forested slopes above and to its south provides another, albeit more difficult, access point to alpine basins of the Peja Pastures, a trail of a contrived third class character. It is possible to circumnavigate Mt. Arapit from the saddle here between Arapit and the Radohimes group to the south east by following the GTZ-Peace Park marked trail north and then east until reaching Peja Pass for the descent back into Theth.

Mt. Arapit's World Record Limestone Cave

The most noteworthy non-visual aspect of Arapit is its world famous cave. The Arapit cave is Albania’s longest recorded horizontal cave at some 2585 recorded meters up to this point, and is also noteworthy as having one of the highest vertical rises of any cave in the world, rising into two vast cylindrical formations some 320 meters above the main cave entrance directly at the base of the yawning South Face below its western peak.

The soluble limestone creates the most interesting shapes - due to the water run off - all along the ascent of Mt. Arapit up its Eastern Shoulder. Some of these rivulets in the limestone gather together to form positive pits, many of which have already been explored by the Bulgarian caving expeditions that have been exploring the area for the last five years.

Hiking and Climbing Routes

East Shoulder Hiking Trail

The regular walk up route is relatively easy, though with a few third class sections and less than obvious route finding. This eastern ridge walk-up was done for the records by Austrians Egon Hoffmann along with companions Feinsheimer and Schatz in 1930. Through the work of the Balkan Peace Park Project and the related cross-national tourism development activities of the German Society for Technical Cooperation (Gesellschaft fuer technische Zusammenarbeit, or ‘GTZ‘), a network of trails, beginning in historical Theth National Park formed by the valley and surrounding peaks, but widening gradually to turn the entire region into a vast multinational parkland, has been developed in the area. While these are all marked with the same white-red striped paint streaks on limestone boulders and rocks along the trails in the area without distinction, they are becoming ever more frequent. They presently mark the clear old donkey path from the various villages of Theth right of the stream bed until switchbacks begin as the trail steepens into the cliff bands below Peja Pass. Soon after the marked eastward turn to the ‘basin of beautiful holes‘, Gropare te Bukura, one is able to follow a turn off west, marked irregularly by cairns, winding through steep meadows and over large limestone dykes until one can see it winding right and northwards over a series of highly striated andOnce over these it turns back left and south-west towards the sharp ridge of the Western shoulder with its freaky drop hundreds of meters over the soHiking up the eastern shoulder to film the summit day of Raki on Arapi. A close look shows the remarkable crack-like rivulets that have been sharply etched in the carst slabs on this, the least steep side of Mt. Arapit.uth face until one reaches t remarkable carst slabs. (While water is available via a ca. 30 minute detour to the 'beautiful holes', it is probably recommended to carry it up the pass from the last spring.) he large summit cairn. Descent reverses the ascent path.

The donkey trail up to Peja Pass from Theth passes this magnificent overhanging rock, which is roughly 120 meters high, and has, on the left side, a series of tiered roofs which are on a scale comparable to the roofs under the East Lavaredo Tower - according to Steffen Heimann, who has followed artifically a free ascent of that famous roof. While sport routes ending below the crag's tip are possible at moderate levels, even one climbing the merely overhanging east side to the top would be a very difficult endeavour.The donkey trail up to Peja Pass from Theth passes this magnificent overhanging rock, which is roughly 120 meters high, and has, on the left side, a series of tiered roofs which are on a scale comparable to the roofs under the East Lavaredo Tower - according to Steffen Heimann, who has followed artifically a free ascent of that famous roof. While sport routes ending below the crag's tip are possible at moderate levels, even one climbing the merely overhanging east side to the top would be a very difficult endeavour.

East Germany Brings Roped Climbing to Arapit - 1959-1960

In 1959 and then again in 1960, a significant group of skilled rock climbers from East Germany visited the Theth and Valbona valleys and achieved a number of notable ascents together with members of the Albanian Alpine Federation. This included the first recorded 5th class routes on Arapit. The group included the leader Harry Durichen, and well-known East German climbers such as Fritz Eske (who later died with three others near the Hinterstoisser traverse on the Eiger), Konrad Stengel, Eckehart Schmidt, Christel Stuntz (later Gladun, who ascended all three 7000m Pamirs), Konrad Linder, Rudi Pimper, and Peter Popp. In one day in July, the redoubtable group - which included the Albanian Alpine pioneer Minella Kapo, who later in 1976 published the first handbook for alpinism in Albanian - put of three different routes on Arapit. These were on the shorter ca. 300 meter 'mountain' rather than 'valley' sides of this beautiful mountain, and specifically on its south-western, north-eastern, and north-western sides. The next year saw three more routes done, including the first on the main south or 'Valley' wall. (Descriptions of the routes have been left, but pictures have not yet been located; the page author has merely translated these descriptions; to his knowledge none of them has been done since 1960.)

The Routes Up Arapit's Mountain Sides

South West Face (German-Albanian Route) - UIAA V

First Ascent - Konrad Stengel, Eckehart Schmidt, L. Olul July 21, 1959. Under the left beginning of the large band of grass above the high scree field, climb the long corner. Then angle up right to past a short face. Then right to a large grass band with a large cave on the right side. Twenty meters right to the beginning of a drainage groove, which is followed to its end past an overhang and a brown section. Follow the face left obliquely and the straight up. A further left traverse and then a log, right leaning crack system leads to a vegetated ledge. From here a chimney and crack leads to the ridge line, which is followed left to the summit.

North East Face - UIAA IV

First Ascent - Harry Duerichen, Harald Loebe, Minella Kapo July 21, 1959. Below the north-east Face, approx. 50 meters underneath the notch, climb the long partially vegetated corner (ca. 70 meters), traverse left and follow a short steep corner to the north-east ridge line. Follow this past a few bands of grass.

The North East Side - UIAA VI

First Ascent - Kujtim Onuzi and Eduard Sheldia, July, 1975.

The only recordedAn original topo of the Onuzi-Sheldia Route up the North East Side. - courtesy Onuzi/Tapia route done on the mountain side of Arapit by a purely Albanian team was completed in July 1975 by Kujtim Onuzi and Eduard Sheldia, and consisted of some five pitches of just under 200 meters length, and with several sections of UIAA VI difficulty. It was repeated in 1981 by Ilir Tapia, Romeo Hanxhari, and Sokol Doka. See topo.

North West Route - UIAA IV-

First Ascent – Joerg Donath, Rolf Heinemann, Vassili Vreto, July 21, 1959. From the north-west face, follow the steep scree to an plateau lying above it. From the hole, climb up right traversing to a band. Then left in the deep groove and the face above to the next band. An overhang leads to a short crack, and then climb the wall straight up above, eventually moving somewhat right to the band above. The face and groove above leads to the summit.

North West Face - UIAA VI-

First ascent Fritz Eske with Harald Loebe and Petrop Kuli, July 6, 1960. In the middle of the north west face a steep scree slope leads to an obvious balcony. From here go left to a small pillar. A short traverse leads to an obvious corner which is followed to the summit.

Ramp Wall - UIAA V-

First ascent – Eberhard Unger and two Albanian companions, July 6, 1960. In the corner right of an obvious large chimney, which leads to a large grass band in the middle of the south-west face. On the right end, follow the ramp up to a crack. Follow the ramp further and then the leaning face leads to the ridge. Follow ridge to summit.

South Face Routes

It is on the main South Face, however, that longest and most difficult roped climbing has been done on Arapit. To be sure, the 1-200 meter long steep faces at the top of the eastward rising gully and forming the shortest and easternmost portion of the South Face were the scene of one to two pitch climbing ventures by members of the Albanian Alpine Federation during their annual meetings in Theth. But it was the strongest party of the East German climbers, led by Eske, who put up the first major route on the south face, which they called the 'Valley Wall.'

Valley Wall - UIAA VI

First ascent - Fritz Eske, Harald Loebe, Eberhard Unger, and Eckehart Schmidt, July 8, 1960. In the left portion of the south wall, well-defined right-leaning rising bands lead to a pillar. Stay left for two pitches until reaching a dark belt of quartz. Follow a corner up left to a large band (cave). First left, then right in steps through faces to another band. Angle up left to a corner with a containing a very large jammed block for ten meters, and then tension traverse right to a crack with an overhang. Follow through this to a band, and then a overhanging crack and crack above to a great band with a pine tree. The crux pitch follows a double crack in a sharp corner leads to another band. The right leading face above leads to steep scree cover slabs to a ridge, which is followed to the top.

Albania Closes Border to Europe

1960 marked the last year that East Germans were able to travel to Albania, as the Hoxha regime, in the wake of the Kruschev reforms in the USSR, broke with the Eastern Bloc and became identified with Chinese Maoism. It was during this period that Albanian alpinism began to develop more on its own, as European influences were now almost completely excluded. Sections of the major sport clubs in the capital, Tirana, sponsored by the Army. These groups were organized by local, with the ‘Partisan‘, ‘Students‘ and ‘November 17‘ club playing an early role in Tirana; and groups from Peshkopi, Berat, Vlora and Korce were also involved. Both summer and winter camps for Alpinists from all over Albania were regularly organized, using Chinese 10 mm braided nylon lines, Chinese klettershue, and Chinese knock offs of Russian carabiners and hard steel pitons. Some of these can still be found on Arapit. During this period, Onuzi and Sheldia put up a new north-east route, but the main event was the much long 'Master's Route' on the main south face done almost a decade later.

Original South Face Route, ‘The Master’s Route‘ - UIAA VI/VI+

Thus it was not until 1985 that the first major complete roped climb was done on the main wall. On July 21 of that year, Ilir Tapia as the leader, with Sokol Doko his second, put an route through the main face, though this traversed left and followed a broken section until it traversed back into the center taking the 3rd class slabs that break the main face between its to summits to the top. This route, done three days continuously, and in 18 relatively short pitches, was rated by them UIAA VI+ with several additional artificial sections; and it has never been repeated. (Note: Below are topo-notes from the first ascent party, but they are difficult to orientate with.)

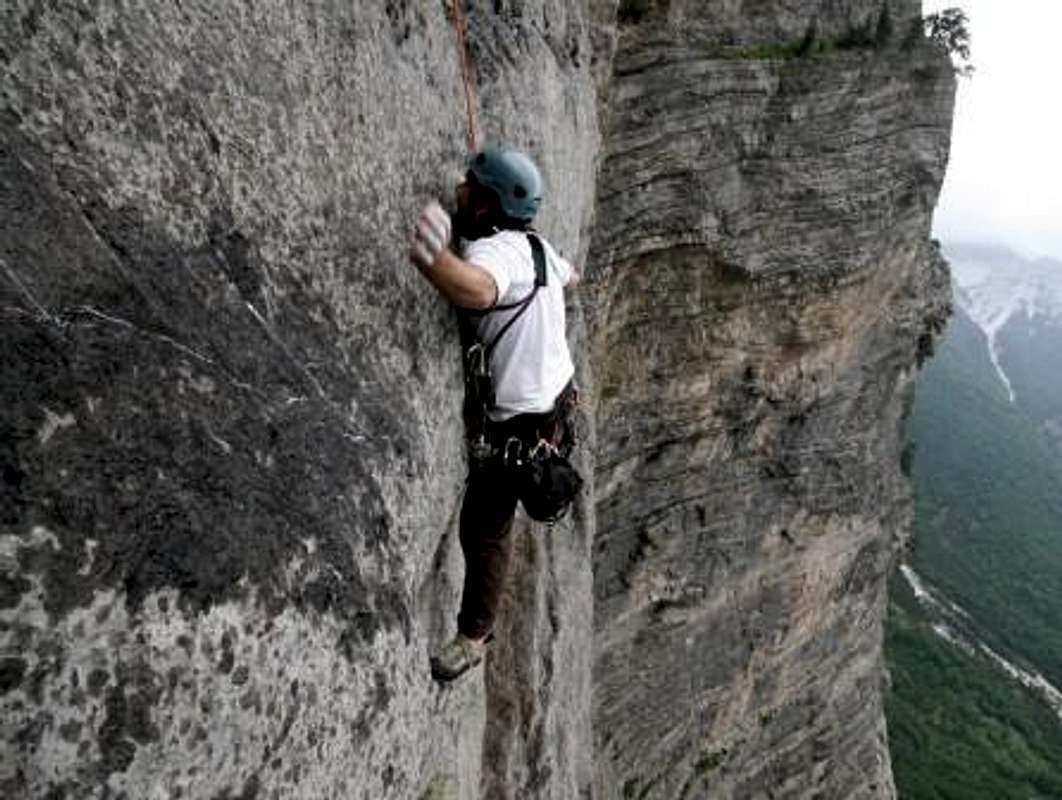

South Face Direct Route – ‘Raki On Arapi ‘ – UIAA VIII, 800m

First Ascent - Krug, Hake, Triller, Wilhelm, Hupe, Duro, Ely, Aug. 2010 The second major route on Arapit, a direct route of the highest part of the South Face, was done in August 2010, nearly 20 years after Albania opened up to tourists at the end of the Cold War, by an international team organized by Gerald Krug and Christiane Hupe from the mountaineering publishing house Geoquest Verlage in Halle Germany.

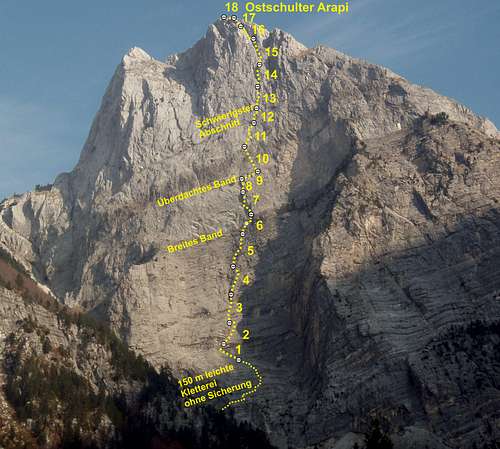

A photo topo of the August 2010 Geoquest route 'Raki on Arapi' (UIAA, VIII/5.11d, 18 pitches, pg). Photo - R. Gentsch, Graphics G. Krug

A photo topo of the August 2010 Geoquest route 'Raki on Arapi' (UIAA, VIII/5.11d, 18 pitches, pg). Photo - R. Gentsch, Graphics G. KrugIt also included as well Axel Hake, Daniel Wilhelm, Ferdinand Triller and Steffen Heimann from Germany, Gerhard Duro from Albania, and John Ely from the United States. This route, named ‘Raki on Arapi‘, was done over a period of four climbing days, and utilized fixed lines up to about the half-way point; it was done completely free on the second ascent, with use of very few points of aid for cleaning and prepping the route by the leading party in 18 long pitches. It was rated UIAA VIII, with obligatory UIAA VII. Two 3/8 in expansion bolts were put in each anchor, and as well at many of the difficult sections, so that the route can now be done safely in one long day without hammer and nothing more than a general assortment of cams and a few passive nuts. The route can also be rappelled from the belay anchors; and the lower six pitches, with only one UIAA VII section protected by a bolt, is quite moderate (IV-V) and makes a nice 'Triassic' pleasure climb (with a small rack to supplement the few fixed protection points) up to the first band and the newly placed Arapit register. An climbing guide, in either German or English, and including a schematic topo, description and details is available for free download at the link below to Geoquest Press. Note: Filmmaker Hugo Scholtz made of video report of this ascent for the Bavarian TV series Bergauf, Bergab (‘Up Mountain, Down Mountain’), available now for viewing on YouTube.

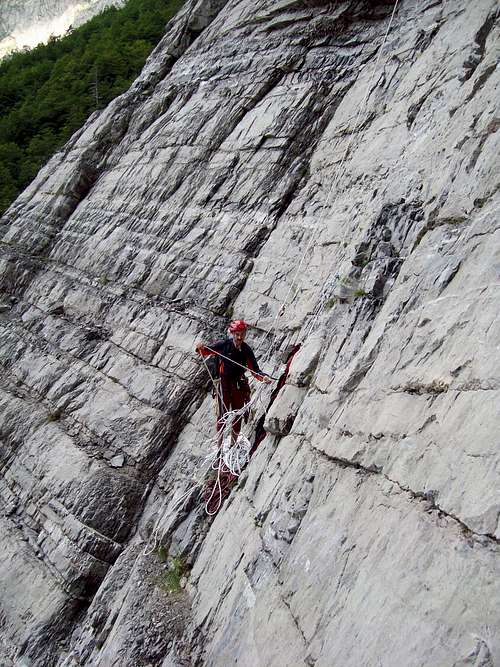

Looking up while jugging the first 100 meters. Long way to top of the big stone. - Photo: Hupe, Open-Air-Image.de

Looking up while jugging the first 100 meters. Long way to top of the big stone. - Photo: Hupe, Open-Air-Image.deSouth Face - 'Cookies and Beer' - UIAA VII (5.10c), 800m

First Ascent - Kranjc, Bracy, Shaefer, May, 20016 On May 27, 2016, Jon Bracy, Mikey Schaefer and Luka Kranjc put in a new route rated UIAA VII up the main face near the Raki Route with sponsorship from the US firm Patagonia. Details are not yet available. South Face Descent A walk-down descent cuts due north across the steep meadow and bands of carst that form the crest of the West Shoulder passing through a gully until one attains the main West Shoulder hiking trail, which can be then followed back down to Peja Pass.

Getting There

The Theth Valley, being perhaps the most beautiful and famous of many in the Albanian Alps, is relatively accessible.

One can drive south via the Montenegran city of Podgorica from continental Europe, and north from Greece via Tirana the capital of Albania; from Kosovo one can make use of the new tunnel-highway that goes from Kukes to the coastal road in a tiny fraction of the previous time. In Tirana the international airport sees some 10-15 flights a day from all over Europe and includes the major European airlines. One turns east off the main coast road between Podgorica the the Albanian city of Shkodra at the town of Koplik, following the main road 30 km to the village of Boge, where soon afterwards the paving ends and a sometimes difficult gravel road carries you over the Thore Pass (1786m) into the valley of Theth (ca. 700 m), a series of small settlements formed into one township. While four-wheel drive is recommended, as the road over the pass is rough, it is possible also in a sturdy two-wheel drive vehicle. One can also rent spaces in a minibus which leaves several times a day from the city of Shkodra or the town of Koplik on the main coast road for ca. 15-25 Euro for a one person, one way trip.

Camping and Accommodation

Most of the villages in the Albanian Alps to do not have formal hotel or motel arrangements, or formal campgrounds either for that matter. However, adventurous tourists, hikers and cavers have been visiting in ever greater numbers since the country opened up after 1991 and especially after it stabilized after the great civil disturbances which followed the collapse of the nation-wide ponzi scheme in 1996 which led to the collapse of the first post-cold war Albanian government and intervention by NATO. Thus, in virtually every inhabited locale, informal bed and breakfast type arrangements including room and full board are available for reasonable prices; and in Theth in particular, these have been formalized into a village wide ‘Han‘ system via the admirable and practical activities of the GTZ.

Such accomodations are widely used by the numerous summer visitors to the valley. Prices in general are fixed at 20 Euro per night inclusive of three full meals of locally produced fare, including drinks and alcohol. In some of the less well visited houses north or south of the main around Theth Gjelai or Theth Ulaj prices are lower by 25-30%. See the guides below for details.

Car camping is slightly more complicated as it is unregulated. It is probably best to have an arrangement in this regard for camping on the property of one of the ‘Han‘ establishment members, which also serves to protect one’s vehicle. Backpacking or camping without a vehicle, especially where discrete, out of the way, or above the timber line where there is relatively little economic utilization of the land beyond goat and sheep herding, is not a problem.

Weather Conditions

The upper Shala Valley around Theth and the high plateau above upon which the most striking of the ‘Accursed Mountain‘ peaks rest is characterized by a unique micro-climate in comparison with the rest of Albania. As one travels up the distinctive incline from Lake Shkodra east wards, the dry coastal area becomes increasingly lush, so that by the time one descends the eastern side of the Thore Pass into Theth, the steep mountain sides are so densely forested and vegetated as to seem nearly tropical and almost impassable. In summers, while hot and hazy in the rest of Albania, it can be cooler and more overcast here, with the clouds blowing in either from the south-west or the north and piling up in and around the steep peaks, wrapping them in fog and mist. The summer heat rising into the mountains produces the usual afternoon alpine weather conditions. Every third day or so, one can expect the rain and the thunderstorms to be strong enough to rinse alpinists off the steep limestone formations. On the whole, however, these periods of stormy weather are generally short, and notably less frequent than in the northern alpine regions. However, no matter how hot the mornings, and especially when headed for above the tree line, have rain gear, warm clothes and headlamps with you before departing. The Theth Valley is covered most of the winter in deep snow, and the snow pack and consequent avalanches close the road over the Thore Pass from November though March or April. Very few families inhabit the valley now year around, with most having alternative dwelling options in the Shkodra area. It is possible to reach Theth in winter by driving up the Kir Valley until one can cross over further south into the Shala Valley and thence on the bad gravel roads following the Shala River to Theth, but even in summer this route takes at least seven hours with four-wheel drive. Historically, most of the winter climbing has been done on the Radohime Massif, which can be reached from the Boge side of the Thore Pass.

Maps, Guides, Sources, and External Links

* Nordalbanien Wanderkarte 1:50,000: Thethi und Kelmand, ed. GTZ, Galli/Hohenwart, March 2009, ISBN 978-3936990461. This is an excellent general map of the region with the most up to date information. * Free maps are available for free download at the Univ. of California at Berkley in 1:50,000, and also at the project ‘Bunker Trails‘ at BunkerTrails.org. These are versions of old soviet era maps, and are are available in 1:50,000 and 1:100,000 variants, but require competence with Russian and cyrillic to sort out the Russian variants of Albanian place names; the care must be taken with the markings for international borders, as the (anti-Tito) Soviets tended to have a liberal view of the Albanian borders by a kilometer or two. * Christian Zindel, Barbara Hausamman: Wanderführer Nordalbanien – Thethi und Kelmend, Huber Verlag, München 2008, ISBN 978-3-940686-19-0. This helpful book is also available in English as Hiking Guide to North Albania: Theth and Kelmand. While it has some idiosyncratic conservative views about Albanian history, its hiking paths have been developed in conjunction with the reliable GTZ, and have accurate GPS based descriptions. It also has a detailed and complete lising of available overnight possibilities with current phone numbers. The English version was produced with help from Antonia Young and Ann Kennard from the U.K. based Balkan Peace Park Project. In the UK it can be obtained from Stanfords Maps and Books in London. * Gerald Krug, Maje e Arapit Climbing Guide: The Highest Wall in the Balkans, Geoquest Press, Halle, 2010. Free pdf download in English or German. * Gerald Krug et al, Trip Report - Raki on Arapi 2010 Geoquest Climbing Expedition, Geoquest Press, Halle. Available here in German or English. * Egon Hoffmann, 'Albanienexpedition', Oesterichsche Alpenzeitung, vol. 53, no. 1115 (1931). * Hans Pankotsch, 'Nordalbanische Alpen 1959/1960', unpublished, no date, Elsasserstr. 3, Dresden. * Peter Popp, 'Zarabitwand', Unterwegs, no. 10 (1960), p. 42. * Aleksander Bojaxhi, Neper Bjeshket e Namura: Kujitime nga veprimtari alpinistik te viteve 1962-1979, Botimet Toena, Tirana, 2005, ISBN 99927-1-999-0. * Renate Ndarurinze, Albanien: Auf den Spuren Skanderbegs, 2nd ed., Trescher Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3897941250. Much of this work seems to have been copied directly from James Pettifer’s famous Blue Guide, but it also has much updated and more current information. * M. Edith Durham, High Albania (1909), available on line at the Univ. of Pennsylvania.