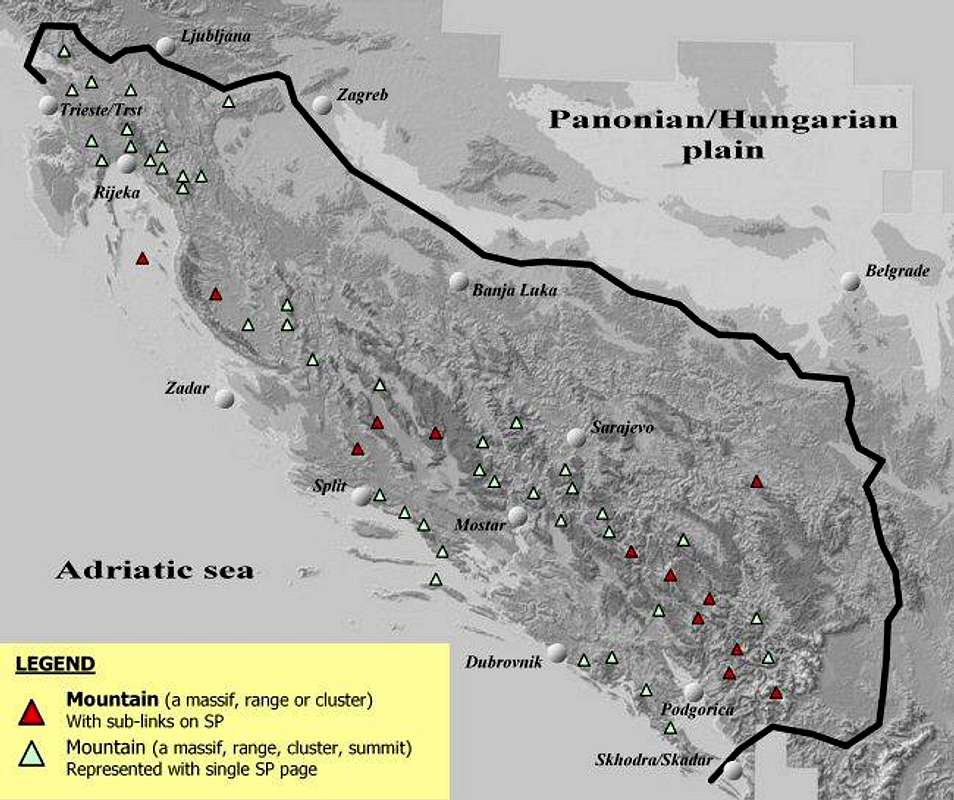

![Borders and internal division]() The borderline of Dinaric Alps then continues over towns of Logatec and Vrhnika in Central Slovenia, cuts through Ljubljansko barje (the centrally located field where Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia lays), then follows river valleys of Temenica and Krka, through Dolenjska region in Slovenia, to meet Sava river in Krško polje (Krko field) - almost following all the way the route of Ljubljana-Zagreb highway. The borderline of Dinaric Alps then continues over towns of Logatec and Vrhnika in Central Slovenia, cuts through Ljubljansko barje (the centrally located field where Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia lays), then follows river valleys of Temenica and Krka, through Dolenjska region in Slovenia, to meet Sava river in Krško polje (Krko field) - almost following all the way the route of Ljubljana-Zagreb highway.

After reaching Sava river in Slovenia the borderline of Dinaric Alps area follows the Sava river basin in eastern direction for more than 400 km (250 mi) through Croatia and touching the northern borders of the state of Bosnia Herzegovina. On this section almost everything south of Sava river belongs to Dinaric Alps mountain system and peri-Dinaric (also in use: peri-Pannonian, od sub-Dinaric) heights, except of some geologically older mountain structures (old Pannonic system), like Prosara and Motajica mountains in northern Bosnia as well as Cer mountain in western Serbia.

After Sava river reaches Serbia proper, the borderline turns southwards along Kolubara river, over the town of Ljig, western foothills of Rudnik mountain, along rivers Dičina and Zapadna (Western) Morava then following Ibar river canyon for a longer stretch, east of large Kopaonik mountain massif, until it reaches the field of Kosovo (Kosova, in Albanian) and Sitnica river.

Now we are in contact-area of geologically younger Dinaric Alps and older Rhodope mountain system. The borderline passes over mountains of Čičavica (Çiçavica or Bjeshkeve te Çiçavices, in Albanian), Goleš (Bjeshkeve te Goleshit, in Albanian) and Crnoljeva (Carralevë or Mali i Carralevës, in Albanian) which separate Kosovo from Metohija field (which is - unlike Kosovo field - Dinaric, settled at the foothils of Prokletije/Bjeshket e Nemuna range). Further following the borderline along Drim/Drin river through northern Albania and encircling Prokletije from SE and S we get to the city of Shkodër (Skadar, in slavic languages), close to Scutari lake (Skadarsko jezero). River Bojana/Bune that takes away the waters from Drim and the Lake into the Adriatic sea makes the southernmost limits of Dinaric mountain system.

Further back, in NW direction, the Adriatic sea borders the Dinaric Alps. All the coast and islands of eastern Adriatic belong to Dinaric system, except two tiny islands in Dalmatia (Croatia), Jabuka and Brusnik which are volcanic by origin. Another exception is western half of Istria peninsula in Croatia and Slovenia which differs in geological origin from Dinaric system.

Following the borderline of Dinaric Alps, passing through a half of Istrian peninsula we get to the important area (the explanation in other following sections) called Kras in hinterland of Trieste/Trst/Triest, and come back to Furlany plain.

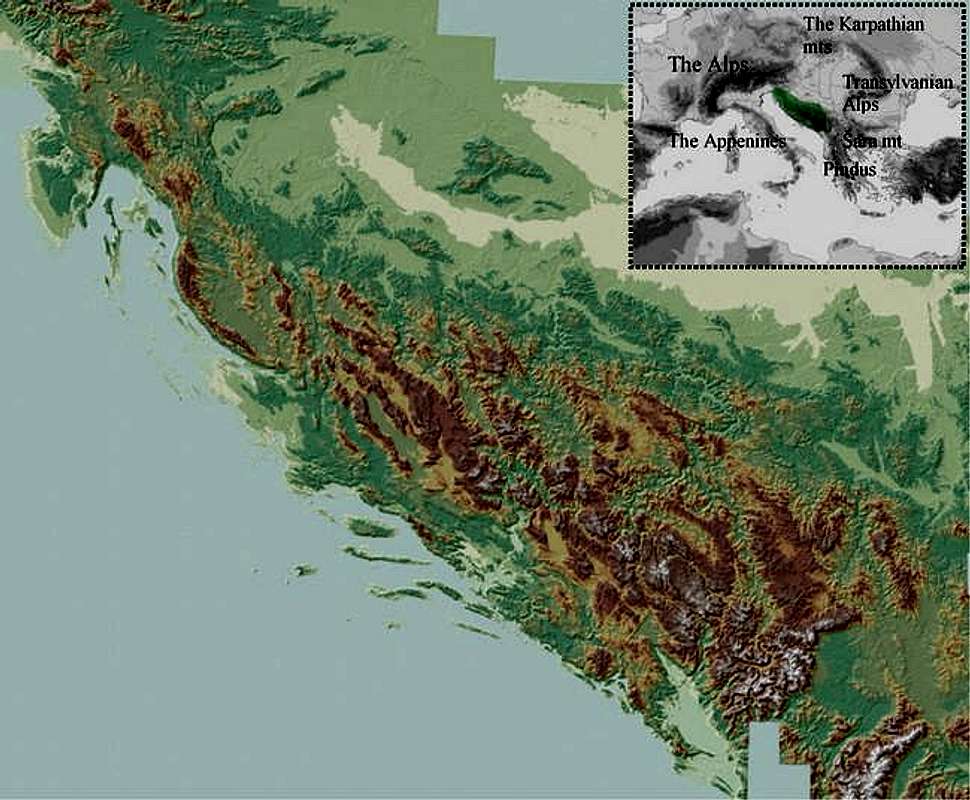

Geology/Tectonics![Komovi from Stavna]() The Dinaric Alps were developed during Tertiary thrusting, which was the most intense in middle Tertiary during Alpine built-up (orogenesys). The Dinaric Alps were developed during Tertiary thrusting, which was the most intense in middle Tertiary during Alpine built-up (orogenesys).

Overall, the main Alpine chains of Europe resulted from the subduction of Tethyan oceanic crust followed by a continent-continent collision between African and European lithospheric plates. The Alpine orogenesys was very complex and occurred in several phases from the middle Cretaceous to the Neogene, of which the collision between Europe and Africa was only one. Much of the earlier deformation in the Alps has been replaced by the later mountain building in the Tertiary.

So it was the same with Dinaric Alps. Later in geological history, after middle Tertiary, the Dinarics were somewhat leveled by natural forces, but in later Tertiary and at the beginning of Quartenary they were built up again to todays´ heights, and this built-up still continues.

The tectonic activity is still present in the area and earthquakes are relatively common features, especially along fault lines.

Dinaric Alps lack in ores (minerals). The exemptions are mountains in Central and Northern Bosnia and some other isolated regions, where some of the mountains are not made of limestone alone, but of other or older rocks.

Little help - Geological Terms:

- Tertiary, the first of two periods of the Cainozoic or Cenozoic Era. c. 66-1.6 million years ago

- orogenesis, mountain building

- Cretaceous, the last geological period of the Mesozoic period, c. 144-66.4 million years ago. The climate was warm and the sea-level rose; cretaceous limestone is limestone laid down during Cretaceous period.

- Quaternary, the last of the geological periods, c. 1.6 million years ago to the present

Dinaric Karst![Karst countryside on Biokovo mt.]() Out of all natural characteristics of Dinaric Alps mountain chain, the most important and the most known is the karst (also known as Dinaric karst). Karst is a type of relief with formed hydrographic and geomorphological shapes and structures, created by water penetrating into soluble rocks as are dolomite, gypsium and especially the limestone. Karstic action is very much present in Dinaric areas that are chiefly composed of limestone. The most of the rocks in the Dinaric Mountains are late Paleozoic and Mesozoic limestones and dolomites. The rest of the Chain is characterized by clastic flysch-like sediments interbedded occasionally with limestone layers. Limestone in this area comes from the former Tethys sea (placed here 200 milion years ago) from which more vast plates arised later, including the Adriatic and Dinaric plates. Marine organism previously deposited on ocean flors, the secretions, shells or skeletons of plants and animals had already formed a layer that was now risen to heights of Dinaric Alps. Out of all natural characteristics of Dinaric Alps mountain chain, the most important and the most known is the karst (also known as Dinaric karst). Karst is a type of relief with formed hydrographic and geomorphological shapes and structures, created by water penetrating into soluble rocks as are dolomite, gypsium and especially the limestone. Karstic action is very much present in Dinaric areas that are chiefly composed of limestone. The most of the rocks in the Dinaric Mountains are late Paleozoic and Mesozoic limestones and dolomites. The rest of the Chain is characterized by clastic flysch-like sediments interbedded occasionally with limestone layers. Limestone in this area comes from the former Tethys sea (placed here 200 milion years ago) from which more vast plates arised later, including the Adriatic and Dinaric plates. Marine organism previously deposited on ocean flors, the secretions, shells or skeletons of plants and animals had already formed a layer that was now risen to heights of Dinaric Alps.

Dinaric karst area is larger than a half of the surface of all Dinarics. This area comprises the south-western half of the Chain, stretching from Italian/Slovenian border all the way to Skadar/Scutari Basin in Montenegro and Albania. The Dinaric mountain regions, already difficult to access, are even more inhospitable thanks to this intensive karstic action. This natural characteristic is one of the main reasons for depopulation of this area and its economic decay, over decades and centuries.

In spite of high rainfall averages in many karstic areas in the Dinarics, the coastal side of the chain has few surface watercourses, because the rainwater quickly sinks underground into the crevices and cavities in the limestone. The more you move inland and to higher grounds the rainfall levels are still high and that supports the forming of dense forest covers (in Notranjska area of Slovenia, Gorski kotar area of Croatia, northern parts of Western Bosnia). Still further inland the limestone areas are less frequent. Locally, there are karstic areas even in Central and SE parts of the Chain, but they give place to other less-porous rocks (schists, grey-wackes, serpentines and crystalline rocks), which hold up surface flows and huge expanses of forests and other vegetation. This kind of karst is called covered, or green karst, because karstic processes are still taking place under the surface mantle of vegetation and humus-soil.

Closer to the coast the bare karst predominates. Here the forests were felled many centuries ago to provide the large quantities of timber required by the coastal towns and villages for shipbuilding and domestic consumption. Some of the largest quantities of timber were taken to Venice, Italy for millions of wooded pylons that hold basements of buildings in this "floating" city. After this deforestation the unprotected topsoil was washed away and the bare white limestone exposed, leaving the barren but magnificent landscape of the bare karst. This areas of bare karst are clearly seen from the Space as white spaces (especially the island of Pag, Dalmatian hinterland, lower Herzegovina and Montenegrin hinterland) contrasting to other wooded areas of Dinarics.

As mentioned previously, the Karst got its name after Kras region in Slovenia and Italy (Italian Carso), a desolate stony and waterless region situated inland from Trieste. The processes of karst formation were first studied by geologists and geographers in this area and the adjective "karstic" has become a general term applied to any area where such processes have been at work (areas in Slovakia, China, USA etc.). The word is of indo-european origin (kar meaning stone). Other terminology of the karst topography, such as doline, uvala, and polje, also originated in Dinaric karst area.

Karst develops after dissolving of limestone in water, which contains carbon dioxide (CO2). This is generally a result of mildly acidic rainfall acting on soluble limestone. The rain picks up CO2 (which dissolves in the water) when passing through the atmosphere.

On the ground, the rain-water sinks into the limestone (which has more than 50 percent of kalcium carbonate - CaCO3) where it picks up more carbon dioxide and form a weak carbonic acid solution (H2O + CO2 -> H2CO3). This mildly acidic water seeps through and begins to dissolve fractures and bedding planes in limestone bedrocks (H2O + CO2 + CaCO3 -><- Ca (HCO3)2 - forming unstable kalcium hydrobicarbonate). Over time these fractures enlarge as the bedrock continues to dissolve. Openings in the rock increase in size, and an underground drainage system begins to develop, allowing more water to pass through and accelerating the formation of karst features. This whole process is called the karstification.

The process of karstification results in a topography with distinctive features and varieties, and overall the Dinaric Mountain region abounds in literally hundreds of examples of karstic landforms including sinkholes, doline(s), uvale(s), polja (fields), karst plains, dry valleys, karren (kamenice), pits, swallow holes (ponori), vertical shafts, disappearing streams, and springs. After sufficient time of water-action, complex underground drainage systems and extensive caves and cavern systems may form (the most of them with again deposited calcium carbonate in forms of stalactites and stalagmites).

The roof of such subterranean cavities may collapse, forming funnel-shaped holes in the ground; the sides of these holes are then gradually levelled down, and a soil is carried into them by the heavy rain. These are the characteristic karstic features known as dolina (doline, plural) or swallowholes - conical depressions, usually ranging in diameter between 10 and 100 ft (cca 30 to 300 ft), with their floors lying 30, 60 or even more feet below the surrounding ground level.

Smaller dolines can also be formed at the intersection of enlarged clefts. In many areas in the karstic upland region (for example on Velebit and Orjen) one doline comes up against another, with only a narrow ridge between them; and when the intervening ridges in time disappear the dolines coalesce into a larger feature known as an uvala.

![Karst formations on Bijele stijene]() Still larger depressions, surrounded on all sides by hills, are called polje (polja, plural). These very typical karstic features have usually very flat floors covered with alluvial deposits of fertile terra rossa. Polja (fields) are agriculturally important because they are basins of good soil in this otherwise barren upland region. Still larger depressions, surrounded on all sides by hills, are called polje (polja, plural). These very typical karstic features have usually very flat floors covered with alluvial deposits of fertile terra rossa. Polja (fields) are agriculturally important because they are basins of good soil in this otherwise barren upland region.

At the edges of many poljes, set at an angle to the floor of the depression, underground rivers emerge, they flow through the polje and disappear again into a hole at the other end. Frequently, however, these holes - ponori (ponor, sing.) are too small to cope with the mass of water when the underground rivers are swollen by heavy rain, or after snow melting; the water then accumulates in the lowest part of the polje, and if the heavy flow of water continues the whole of the polje is transformed into a periodical lake. In some fields this flooding can last for several months. They are usually dry again by the beginning of summer, but if the autumn rains come early they may again be flooded in late summer, which produces lots of problems for people farming this small (and maybe, the only) parches of arable land. The villages and hamlets in which they live avoid the floor of the polje and stay out of reach of the water on the arid slopes around its edges which are not suitable for cultivation.

The water which sinks into the ground in the karstic uplands finds its way to another polje and lower laying land or the sea through underground channels. One of the largest such system is Pivka river system in Notranjska region of Slovenia, with more such subterranean "tunnel valleys" - one of them the famous Postojna Caves (other such rivers are river Lika in Croatia, Buna in Herzegovina, Reka river in Slovenia).

After their disappearance into a ponor many rivers re-emerge again in the form of karstic springs on the coast or even under the sea (vrulja spring). Along the the eastern Adriatic coast between Rijeka and Kotor Bay (Boka kotorska) only few rivers reach the sea in deeply, steep-sided canyons (Zrmanja, Krka (Dalmatian), Cetina and Neretva rivers). A normal surface drainage system develop in the areas of less permeable clays and marls which occur here and there in the limestone region, but as soon as the rivers reach limestone territory they disappear underground like the others.

Little help - Basic Terms on Karst:

- calcite, main constituent of limestone rocks

- dolina, this is a local (South-Slavic) and also a scientific term for valley; also a depression in the surface of limestone formed by running water dissolving the rock carrying soluble calcium carbonate away and leaving insoluble material as a clay-like deposit. Sink-holes or swallow-holes are smaller, and polje larger similar phenomena.

- karst, distinctive type of landscape developed on and within limestone. The name derives from the Karst regions

- limestone, sedimentary rock, consisting mainly of mineral calcite (calcium carbonates), usually of marine organism deposited on ocean flors, the secretions, shells or skeletons of plants and animals. It makes up approximately 10 percent of the total volume of all sedimentary rocks.

- limestone color, pure limestones are white or almost white. Because of impurities, such as clay, sand, organic remains, iron oxide and other materials, many limestones exhibit different colors, especially on weathered surfaces.

secondary calcite, mineral calcite, deposited by supersaturated meteoric waters (groundwater that precipitates the material in caves). This produces speleothems such as stalagmites and stalactites. - polje, a local (South-Slavic) word for a field; as a scientific term also large flat-floored depressions in limestone areas.

- sinkhole, fairly small hollows found in limestone areas.

- travertine banded, compact variety of limestone formed along streams, particularly where there are waterfalls and around hot or cold springs. Calcium carbonate is deposited where evaporation of the water leaves a solution that is supersaturated with chemical constituents of calcite. Tufa, a porous or cellular variety of travertine, is found near waterfalls.

- marl, clay deposit, rich in calcium carbonate, often formed as glacial deposit or resulting from the weathering of impure limestones.

- pothole, usually funnel-shaped vertical shafts formed in limestone. Underground they may be interconnected by, frequently water-filled passages

Sources used on Karst chapter: Encycl.opentopia, Baedeker´s ; Yugoslav Encyclopedia, 1966; Mountains of Slovenia, Cankarjeva zalozba, 1989.

ClimateThe mountains of the Dinaric Alps are under influence of three basics types of climate.

The heights of the narrow coastal belt and the islands of the Adriatic are under influence of Mediterranean climate with hot dry summers and mild rainy winters. But higher and the highest mountains in the coastal area have more complex climate. Sunny slopes of those ranges are very hot in summer. Also, warm humid air that comes from the sea, very often crashes with colder air above those mountains, so the higher areas can have a lots of snow in winter and overall, the first rows of high ranges into hinterland (Orjen, Velebit, Gorski kotar), receive a huge amount of precipitation - yearly averages (some of the highest in Europe) are between 3000-5000 mm of precipitation (Crkvice on mt. Orjen have an average of 4640 mm, the absolute maximum in Europe).

![Velebit mt. from Krk isl.]() High mountains of Maritime zone and parts of the Highest Dinaric Alps are strong barrier for Mediterranean influences to penetrate further inland. On some places on the coast the influence of the Mediterranean climate is restricted to just few kms into inland, or less, because of the height of coastal mountain barrier - Velebit mountain, especially. In other areas, like river valleys (Neretva, Zeta) or lower mountain passes, warmer Mediterranean air penetrates further inland, away from the coast, and reaches the first rows of mountains in the Central Dinaric Belt. The best example is relatively warmer climate of Lower Herzegovina all the way to the city of Mostar (some 40 km away from the coast) and the warm Mediterranean and cold Mountain and Continental climates crash very often over the mountains of High Herzegovina, north of Mostar (like Prenj mt.), which is know for its unpredictable weather conditions. High mountains of Maritime zone and parts of the Highest Dinaric Alps are strong barrier for Mediterranean influences to penetrate further inland. On some places on the coast the influence of the Mediterranean climate is restricted to just few kms into inland, or less, because of the height of coastal mountain barrier - Velebit mountain, especially. In other areas, like river valleys (Neretva, Zeta) or lower mountain passes, warmer Mediterranean air penetrates further inland, away from the coast, and reaches the first rows of mountains in the Central Dinaric Belt. The best example is relatively warmer climate of Lower Herzegovina all the way to the city of Mostar (some 40 km away from the coast) and the warm Mediterranean and cold Mountain and Continental climates crash very often over the mountains of High Herzegovina, north of Mostar (like Prenj mt.), which is know for its unpredictable weather conditions.

The most of the Dinaric Alps area has classical mountainous or Alpine climate with large rainfalls, short and cool summers and long winters with abundant snowfalls. In winter time the cold air descends from surrounding mountains into lower laying mountain fields and valleys. Those areas have lower winter temperatures than the mountains surrounding them. In summer-time the process is reverse, the bottom parts and the slopes warm up much faster than surrounding mountains.

The lowest temperatures in the Dinarics, were measured not only on the highest mountain tops, but on some of the highlands in the area, especially those situated further away into land mass (so called mrazišta= frosty locations, like Pešter highland (Pešterska visija/visoravan, orig.), Igman plateau, Gorski kotar plateau, with record temperatures measured at -40 degrees C and lower.

Mountains on the northern edge of the Dinaric Alps and the lower laying areas of the North-Eastern chain have a mixture of mountain and continental climates (of Central-European or Balkan types), sometimes this climate is called moderate-continental and mountainous. Those areas have warm summers but also cold winters.

Divisions of the Dinaric AlpsPrinciples of structuring Dinaric Alps

The main idea of forming a mountain group is the fact that there are mountains that share the same or similar characteristics. The geomorphology is probably the most important factor in most of the cases, the one that obviously, or just physically, separates a cluster of mountains from another one. There are other important factors too, one of them a traditional folk's perception of a group. And there is a practical reason too, and that is a need to organize large fields of activities into smaller fragments which are then easier to work or cope with.

This is an idea that mostly worked in case of dividing the European Alps into groups and subgroups. But what to do in a case where geomorphology and relief is so complex and so different than "the classical one" found in the European Alps (where mountain groups are often separated by deep rivers, glacial valleys or by distinctive mountain passes, and folk tradition, too)?

Namely, trying to set up the structure of the Dinaric Alps, that would be based on real terrain situation and also practical enough for understanding the structure of the Dinaric Alps, I was faced with following problems:

![A view from Velebit]() | - Dinaric Alps abound in different morphological structures. Although they all make one unique chain and share other similarities, by traveling from NW to SE throughout Dinaric Alps you could witness lots of varieties among the mountains and groups.

- The literature and data sources on many & many mountains in the Dinaric Alps are very scarce, and it is difficult to find them. The most of the mountains don't have a serious mountaineering/tourist guide or even anything similar.

- People from one side of the mountain have different names and different group structuring, than those from the other side.

- The same morphological massif was divided by historical state or national borders and through history two separated parts got different names, while no common name exists today. Most of the times no single name exist for some mountain massifs but instead of it people gave the name after the region where they are situated (f.e. high plateaus of Notranjska in SE Slovenia and Gorski kotar region in W Croatia, which are in fact one huge mountain mass).

- Although, to group mountains in Dinaric Alps according to the state where they are situated, could be the easiest way to do it, in many cases political borders would limit the perception of a mountain and a group as a whole. Because of this, my intention was to try to structure the Dinaric Alps by obeying both natural and cultural tradition, trying to achieve the most logical results.

|

- First step - Dinaric Alps´ division into major morphological units - usually Dinaric Alps are divided into 3 parallel belts (they are, in fact, elongated chains consisting of more mountain ranges and massifs). These are: Maritime (South-Western), Central and Norht-Eastern Belt (see Map 3.).

- Second - recognition of distinctive geographical mountainous areas which consist of more mountain groups.

- Next, to recognize individual morphological and tectonic mountain groups. And in the Dinaric Alps the most common formations that would make a mountain group would be one those: a large massif, a larger cluster of mountains and summits with common features or very common one, a mountain range.

- Further step would be to recognize more sub-ranges and sub-groups inside individual mountain groups (enough work for group maintainers).

- Some major mountains and mountain massifs are being treated as individual mountain groups (which in fact they are because of theirs´ complexity; these refers mostly to mountains like Velebit, Prenj, Durmitor).

- The last stage would be naming the morphological zones, geographical regions, mountain groups and other sub-ranges and sub-groups, primarily trying to obey traditional names, where (and if) such name exist.

- For easier use on SP, in case the previously mentioned principle was difficult to apply, I have named the group after dominant mountain or other logical and relevant factor.

Structuring the Dinaric AlpsOther divisions of the Dinaric AlpsRegional OverviewSouth-Western or Maritime BeltTABLE 1. Mountains of SW or Maritime BeltMaritime Belt - DescriptionCentral Belt or High Dinaric AlpsTABLE 2. Mountains of Central Belt in Dinaric AlpsCentral Belt - DescriptionNorth-Eastern BeltTABLE 3. Mountains of North-Eastern BeltNorth-Eastern Belt - DescriptionMountaineering HighlightsOther FeaturesRivers![Cascades on Una River]() The rivers of the Dinaric Alps belong to two watersheds; they bring their waters into the Adriatic (around 25 percent) and the Black sea (75 percent). The main rivers flowing into the Adriatic sea are Soča/Isonzo (137 km), Krka (Dalmatian) (71 km), Cetina (106 km), Zrmanja (69 km), Neretva (213 km), Zeta (65 km), Morača (97 km), Bojana/Buna and Drim/Drin (109 km). These rivers flow through karst region, they spring as gushing and abundant springs (s.c. vrelo) and have relatively short flows with many falls and canyon-like valleys. The rivers of the Dinaric Alps belong to two watersheds; they bring their waters into the Adriatic (around 25 percent) and the Black sea (75 percent). The main rivers flowing into the Adriatic sea are Soča/Isonzo (137 km), Krka (Dalmatian) (71 km), Cetina (106 km), Zrmanja (69 km), Neretva (213 km), Zeta (65 km), Morača (97 km), Bojana/Buna and Drim/Drin (109 km). These rivers flow through karst region, they spring as gushing and abundant springs (s.c. vrelo) and have relatively short flows with many falls and canyon-like valleys.

Further to the north and north-east river 945 km long Sava river (with spring in Slovenian Julian Alps) is the most important Danube tributary, and although it flows on the edges of Dinaric mountain system it receives the most of Dinaric waterflows. The most important Sava tributaries are Krka (Slovenian), Kupa (296 km), Una (214 km), Vrbas (227 km), Bosna (273 km), Drina (346 km) rivers. The other important rivers are Korana, Mreznica, Dobra, Sana, Pliva, Lasva, Spreča, Rama, Tara, Piva, Lim, Ibar (276 km), Zapadna (Western) Morava (295 km) and Kolubara (106 km).

Another interesting feature in the Dinaric Alps are so called sinking creeks or sinking rivers (and underground streams) in Dinaric karst, one of them Trebisnjica (100 km) in Eastern Herzegovina, being the largest of a kind in Europe. Other such rivers are Reka (Notranjska) (44 km), Lika (76 km) and Gacka (48 km).

Because the most of the rivers are mountainous in their character they have many waterfalls, they are rich in salmonoide-type fish and some of them were also dammed for hydro-electrical power plants (Drina, Piva, Neretva, Vrbas).

The only river which cuts its way through Maritime and Central Dinarics is Neretva, providing a passage into the valley of the river Bosnia by way of the Ivan-sedlo pass (967 m). Despite the fact that the most of Dinaric rivers cut through limestone gorges, many of them, especially in northern and NE parts of the Chain (Vrbas, Bosna rivers), have long been important traffic routes, because there were no easier options (no low laying mountain passes). The other rivers that carved their canyons deep in a limestone rock, thus making unapproachable barriers, blocked any serious contacts and travel for long time and were known throughout history as division-lines between family klans and regions (f.e. Tara river).

Lakes![Bukumir Lake in Montenegro]() There are more than 200 lakes throughout the Chain. They are of karstic, tectonic, glacial, travertine, fluviokarstic, or fluvial origin, and also the artificial ones, but the most of them are much smaller than 10 sq. kmKarstic lakes formed by karstic erosion are f.e. Red and Blue lakes near Imotski (Croatia, Dalmatia)Travertine lakes are formed by accumulation of sediments of marl in riverbeds, like are Pliva lake (Plivsko jezero), Plitvice lakes (Plitvička jezera).If erosion is combined with tectonic sinking, those lakes are known as karstic-tectonic, such is Scutari lake (Skadarsko jezero).A type of karstic lakes are also periodically flooded areas of some karstic fields such are: Cerknica field (Cerknisko polje), Popovo field (Popovo polje), Livno field (Livanjsko polje), Kosinj field (Kosinjsko polje) and others.Glacial lakes can be found in high mountains of Montenegro and Bosnia&Herzegovina. They are mostly of smaller size but very attractive so many people call them "mountain eyes" (18 such lakes are on Durmitor, 6 on Bjelasica). There are also some lakes of glacial origin situated at the foothills of high mountains, where the water was dammed by the sediments drifted here by the glaciers. Such lakes are Plav lake (Plavsko jezero), Biograd lake (Biogradsko jezero). There are more than 200 lakes throughout the Chain. They are of karstic, tectonic, glacial, travertine, fluviokarstic, or fluvial origin, and also the artificial ones, but the most of them are much smaller than 10 sq. kmKarstic lakes formed by karstic erosion are f.e. Red and Blue lakes near Imotski (Croatia, Dalmatia)Travertine lakes are formed by accumulation of sediments of marl in riverbeds, like are Pliva lake (Plivsko jezero), Plitvice lakes (Plitvička jezera).If erosion is combined with tectonic sinking, those lakes are known as karstic-tectonic, such is Scutari lake (Skadarsko jezero).A type of karstic lakes are also periodically flooded areas of some karstic fields such are: Cerknica field (Cerknisko polje), Popovo field (Popovo polje), Livno field (Livanjsko polje), Kosinj field (Kosinjsko polje) and others.Glacial lakes can be found in high mountains of Montenegro and Bosnia&Herzegovina. They are mostly of smaller size but very attractive so many people call them "mountain eyes" (18 such lakes are on Durmitor, 6 on Bjelasica). There are also some lakes of glacial origin situated at the foothills of high mountains, where the water was dammed by the sediments drifted here by the glaciers. Such lakes are Plav lake (Plavsko jezero), Biograd lake (Biogradsko jezero).

Table 5.

| NATURAL LAKES IN DINARIC ALPS | | The Name of the Lake (altitude) | Surface Area (Depth) | Country | | Scutari Lake (Skadarsko jezero) 6 m | 391 sq. km (44 m) | Montenegro/Albania | | Vrana Lake (Vransko jezero) 0.7 m | 30 sq. km (4 m) | Croatia (Dalmatia) | | Prokljan lake (Prokljansko jezero) 0.5 m | 11.4 sq. km (20 m) | Croatia (Dalmatia) | | Vrana Lake (Vransko jezero) 14 m | 5.75 sq. km (84 m) | Croatia (Cres Island) | | Blidinje lake (Blidinjsko jezero) 1183 m m | 3.2 sq. km (84 m) | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Deransko lake (Hutovo blato) | 2.5 sq. km | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Plitvice lakes (18 in system) 503-636 m | 1.98 sq. km (49 m) | Croatia (Plitvice Lakes) | | Plav lake (Plavsko jezero) | 1.2 sq. km (9 m) | Montenegro | | Pliva lake (Plivsko jezero) | 1.1 sq. km (35.6 m) | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Durmitor lakes (18 lakes) | 0.95 sq. km | Montenegro | | Bjelasica lakes (6 lakes) | 0.59 sq.km | Montenegro |

Table 6.

| PERIODICAL LAKES IN DINARIC ALPS | | The Name of the Lake (altitute) | Surface Area (Depth) | Country | | Cerknica Lake (Cerknisko jezero) | 12-26 sq. km (3 m) | Slovenia |

Table 7.

| ARTIFICIAL LAKES IN DINARIC ALPS | | The Name of the Lake (altitude) | Surface Area (Depth) | Country | | Piva Lake (Pivsko jezero) | 112 sq. km (187 m | Montenegro (Piva river) | | Buško blato/Buško jezero (Busko lake) 716.5 m | 56 sq. km (17,3 m) | Bosnia and Herzegovina/Croatia | | Bileca Lake (Bilecko jezero) 400 m | 33 sq. km (104 m) | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Modrac Lake (Modracko jezero) 200 m | 17 sq. km | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Jablanica Lake (Jablaničko jezero) 270 m | 14.38 sq. km (70 m) | Bosnia and Herzegovina (Neretva river) | | Peruća lake (Perućko jezero) 360 m | 13-15 sq. km (64 m) | Croatia (Cetina river) | | Zvornik lake (Zvorničko jezero) 140 m | 8,1 sq. km (28 m) | Bosnia and Herzegovina/Serbia (Drina river) | | Zlatar lake (Zlatarsko jezero) 290 m | 7.2 sq. km (75 m) | Serbia (Uvac river) | | Potpec lake (Potpecko jezero) 400 m | 7 sq. km (40 m) | Serbia (Lim river |

Animal life of the Dinaric Alps![A bear cub on Velebit mt.]() | In work! |

Large Carnivores

Endemic Species

| The Olm or Proteus (Proteus anguinus)

Excellent Wikipedia-page on this endemic animal (človeška ribica in Slovenian and čovječja ribica in other souh-Slavic languages, both literally translated as "the humanoid fish", because of its skin-color that resembles to the human one) |

![Deep preserved forests]() | . |

Nature ProtectionMorphological, Climatic, Biological and other diversities, as well as Tourism and Ecological needs were the main reasons for protecting some areas in Dinaric mountain chain. And it is really striking how different those national parks and protected areas are in their character.

But sometimes, despite the intentions to protect the nature, there are some part in Dinarics (sociological and cultural reasons) where local people do not have very much active attitude in protecting their natural surrounding (trash dropping!), and the only reason why many mountaineous areas are still being preserved is shear underdevelopement and underpopulation in those areas.

The most of the states in Dinaric Alps have one or more national parks and strictly protected areas. Here is a review of the National Parks in the Dinaric Alps:

Table 8.| PROTECTED AREAS IN THE DINARIC ALPS (here presented national parks, only) | | The Name of protected Area | Main Features | Country | | Risnjak National Park | Unusual richness of natural phenomena caused by its position between Alps and Dinaric range, which causes different climatic, geological, petrographical, and other characteristics of the area; forest vegetation covers 98 percent of the Park; karst phenomena - sink holes, pits, springs, abysses; protected and endemic species of flora and fauna; presence of big mammals - bear, wolf, lynx, chamois; possibilities for recreation - trekking, mountain biking, tour skiing. Risnjak NP Link | Croatia | | Plitvice Lakes National Park | Established in 1949, enlisted in UNESCO - World Heritage List: 1979. Main features: diverse forest communities cover more than 75 % of the park area; unique karst phenomenon-between the mountain ranges of Mala Kapela and Licka Pljesivica there is a series of 16 lakes arranged as cascades, separated by travertine barriers; karst phenomena - caves, sinking zones, pits, ice caves; preserved forests of beech and fir, relic forest communities; high biological diversity -1146 plant species (72 endemic, 22 protected), 150 birds; habitats of big predators - bear, wolf, lynx, wildcat Specially protected areas: special forest reserve - virgin forest Corkova uvala. Plitvice NP Link | Croatia | | Northern Velebit National Park | Numerous karst phenomena and caving objects - deep pits, karrens, sinkholes; preserved forest communities; high biological diversity, plenty of endemic species; landscape diversity - picturesque valleys, pastures, rocks, screes; remains of traditional architecture - old summer lodgings Specially protected areas: strict reserve Hajducki i Rozanski kukovi, special botanical reserves: Visibaba, Zavizan-Balinovac-Velika kosa with Velebit botanical garden. Northern Velebit NP (Sjeverni Velebit NP)Link | Croatia | | Paklenica National Park | Canyons of Velika and Mala Paklenica have plenty of geological, hydrological, karst, floristic and faunal characteristics; rich flora - about 800 species (40 endemic); diverse and rich fauna - especially important is the presence of the griffon vultures; rich cultural heritage - indigenous architecture, water mills, felting mill, archaeological locality Paklaric; most famous Croatian climbing area for climbers and alpinists. Paklenica NP Link | Croatia | | Una River National Park | Established as a National park in May, 2008. It extend over the areas of the Upper Una river flow and its river gorge, lower Unac river flow with its river gorge and area between Una nad Unac rivers | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Sutjeska National Park | NP attractions are Sutjeska river gorge, undisturbed valleys, thick mixed woods, mountain pastures, high karst formations, high mountain massifs (Maglic, Zelengora, Volujak, Vucevo), more glacier lakes, well known strictly protected Perucica a primeval forest of unique beauty and the biggest preserved primeval forest in Europe; Skakavac waterfall in Perucica; fauna and flora, including lots of endemics; historical significance of the place. Sutjeska NP Link | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Kozara National Park | Occupies a central part of mount Kozara (Mrakovica at 806 m). Forest covered hills, lakes and streams. Orohidrographic area; source of more crystal clear rivers as well as numerous springs. From Mrakovica with its central position in NP more valleys, mountain slopes and ranges decorated with meadows, in all directions. Historic importance. Activities: walking, observation of wild life.Kozara NP Link | Bosnia and Herzegovina | | Durmitor National Park | Enlisted in UNESCO - World Heritage List in 1980, - Biosphere Reserve in 1977. Magnificent scenery; glacial feautures, lakes and valleys; morphological features - mountain ranges and summits rising from high karstic plateaus, deep river canyons; endemic flora and fauna, primeval forests (more than 400 years old, 50 m high trees (spruce, fir, dark-pine, beech); speleological objects, caves, chasms, holes; tourism: mountaineering, speleology. Tara river canyon (41 percent of NP surface area) enlisted in UNESCO/MAB, deepest in Europe with 1000-1200 m high sides; crystal-clear water, rafting. Durmitor NP Link | Montenegro | | Biogradska gora National Park | Situated in NE Montenegro in central part of Bjelasica massif, encircled with mountain summits higher than 2,000 m, streams and valleys. Glacial features, lakes, moraines. Biogradska gora a primeval forest and strictly protected reserve. Traditional local architecture in villages, katuns (shepherds´s settlements), mills. Close to Tara and Lim rivers. Biogradska gora NP Link | Montenegro | | Skadarsko jezero (Scutari Lake) National Park | Fresh-water fauna and flora; flooded woods of willow and poplar in Bojana/Bune river delta, vast birds nesting areas (cormorant, heron, egret, pelican and other); fresh-river fish; cultural heritage, old monasteries and churches; close to Rumija mountain (mountaineering). Skadarsko jezero NP Link | Montenegro | | Lovcen National Park | Biodiversity, rare and endemic species; rocky ground, karstic and oromediterranean vegetation; forest reserves (maritime beech-tree); cultural heritage. Lovcen NP Link | Montenegro | | Tara National Park | Protected countryside of Tara mountain (do not mix it with Tara river in Montenegro), river valleys and canyons, waterfalls, caves and other karstic features, mixed wooded areas, primeval forests, rare plant and animal species; protected Pancic pine-tree areal. Tara NP Link | Serbia | | Theti National Park | Situated in the North Albanian Alps (Prokletije or Bjeshket e Nemuna), 70 km far from Shkodra/Skadar. River of Thethi, with an outpouring of about 1000-1300 l/sec. Waterfall of Grunasi natural monument Variety of habitats and vegetation. Area of lynx-lynx with about 50 principals specie. Info on Thethi Area | Albania | | Lugina e Valbones (The Valley of Valbona) National Park | Situated 25-30 km in northwest of the city of Bajram Curri. It expands among high mountains; fantastic colors in every season, valley full of labyrinths and surprises. Its scientific, tourist and health recovering values; bio-diversity of national and international importance. Rocky and attractive peaks, the sides covered with wood, the flow of brooks and river Valbona. Tourism, fishing, relaxation, amusing and mountain climbing as well as winter sports. In the inner part of the Park lots of grottos and caves (the most eminent Cave of Dragobia, with historical importance, too). | Albania | | Krka National Park | Preserved and insignificantly altered ecosystem; the area of 109 square kilometers along the Krka River; famous for its travertine waterfals and cascades, and the river canyon overall is a natural and karstic phenomenon. Krka NP Link | Croatia | | Mljet National Park | "Mljet" NP covers NW part of Mljet island, 5.5 ha of protected land and surrounding sea. Protection of an original ecosystem in the Adriatic. Unique panoramic landscape of well intended coastline, cliffs, reefs and numerous islands, and rich topography of the nearby hills, which rise steeply above the sea and hide numerous ancient stone villages. Outer coastline exposed to the south sea and therefore steep and full of "garmas" collapsed caves. The salt lakes are a unique geological and oceanographic phenomenon. The Mediterranean karst landscape hides two natural specialties - typical karst underground habitats: half-caves, caves and pits and brackish lakes, which vanish from time to time. Beautiful, rich forests. Cultural heritage. Mljet NP Link | Croatia | | Kornati National Park | In the central part of croatian Adriatic Sea, about 15 Nm to the west from Sibenik town, or 15 Nm to the south from Zadar town; amazing group of islands named Kornati archipelago; 89 islands, islets and reefs within the NP; the most indented group of islands in the Mediterranean. The land part of NP covers less than 1/4 of area, values of its landscapes, the "crowns" (cliffs) on the islands facing the open sea, interesting relief structures; submarine area, biocenosis considered to be the richest in the Adriatic Sea, and also the magnificent geomorphology of the sea bed attracts divers. Exceptionally rich flora and fauna. The land section of the Park; app. 700-800 vascular plant families; variety of birds. Hiking: numerous hilltop view locations; interesting geological and geo-morphological phenomena seen from the hilltops.

Kornati NP Link | Croatia | | Velebit Nature Park | Enlisted in UNESCO/MAB - Biosphere Reserve in 1978. Longest mountain of the Dinaric range - 145 km; karst phenomena - barren rocks of different shapes, canyons, valleys, caves and pits; hydrogeological phenomena - karst rivers with travertine barriers, underground flows which emerge in the sea as submarine springs; landscape diversity - alteration of barren limestone rocks with beech, fir and spruce forests; biological diversity - 2700 plant species, numerous endemic species of flora and fauna, particularly in the underground and waters Specially protected areas: 2 national parks: Paklenica and Sjeverni Velebit, protected landscape Zavratnica, geomorphologic nature monuments: Cerovacke pecine and Modric cave, palaeontological nature monument Velnicka glavica, special forest reserve Stirovaca - virgin forests of beech and fir.

Velebit Nature Park Link | Croatia | | Golija Nature Park | Enlisted in UNESCO/MAB - Biosphere Reserve in 2001. Golija-Studenica Biosphere Reserve is situated in southwestern Serbia and belongs to the inner zone of the Dinaric mountain system. It covers a mountainous region and includes a mosaic of different ecosystems such as forests, shrubs and lakes. The local population cleared parts of the forests over centuries and thus created species rich pastures and meadows which are still maintained today. The biosphere reserve includes the Studenica Monastery, which is a cultural World Heritage site and a popular tourist attraction.

Golija-Studenica Biosphere Reserve | Serbia |

Practical InformationGetting There and AroundWhen to ClimbRed TapeCamping and Accomodation - Mountain lodges and hutsMountain (Weather) ConditionsMountaineering Associations and OrganizationsMountain Rescue ServicesUsefull LinksThe More Remote History of This Page.. |

|

|

|

|

|

221112 Hits

221112 Hits

99.55% Score

99.55% Score

117 Votes

117 Votes