|

|

Mountain/Rock |

|---|---|

|

|

37.86030°N / 107.9842°W |

|

|

San Miguel |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Mixed, Scrambling, Skiing |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

14017 ft / 4272 m |

|

|

Overview

Each state has certain activities or images that define it. With Colorado, some may think of: skiing/snowboarding, the Coors brewery in Golden, the town (and ski area of Vail) or perhaps even the changing of the aspens every fall as they done their temporary golden and orange coats in lieu of green. Others may mention the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, the New Belgium Brewery in Fort Collins or the Flatirons in Boulder. Even though all these are solidly correct (they come to my mind as well), Colorado can never-the-less be summed up in a singuler word...mountains.

Pikes Peak is largely considered to be 'America's Mountain.' It was after all, the inspiration for the nationalistic poem, 'America, the beautiful.' There is also Mt. of the Holy Cross which, held America's religious attention for a few decades. And lest we forget Colorado's poster children for mountain imagery, The Maroon Bells located outside Aspen.

However, there is another mountain equally well known and respected. Hidden in the southwest corner of the state in the epochal San Juan Mountains, this particular peak has come to represent Colorado so candidly and thoroughly, that it now graces every can and bottle of Coors beer. No talk of Colorado mountains is complete without mentioning Wilson Peak.

In the mid to late 1800's as the now famous Hayden Surveys were exploring and surveying the west, their travels took them through the rugged and largely unknown San Juan Mountains. It was at this period in time, that the cartographers finally set eyes on what would become known as Wilson Peak. It was a mutual decision among most of the group involved to name this singular peak after the surveys chief cartographer and mapmaker, A.D. Wilson in 1874 (Allen David Wilson). Of note, it has been suggested in years past, in changing the peaks name to Frankin Rhoda Peak, the younger half-brother of A.D. Wilson. The problem with this, is that there is already a peak in the San Juan's named after Franklin, Mt. Rhoda. To his credit, Franklin made many first ascents in the San Juan Montains as it was.

Other than gracing the containers of many "adult beverages," Jeep has also used this peak and WIlson Mesa in many of its' ads attempting to showcase how rugged its' products are in commercials. More currently however, the peak was used in the Quentin Tarantino movie, 'The Hateful Eight' as the backdrop to all the hi-jinks and murders at Minnie's Haberdashery. The movies Scout Manager, John Minor, was able to secure permission from the Schmid Family who have owned the land (ranch) since the late 1800's.

At 14,017', it certinly isn't the highest of Colorado's Fourteener's. Located approximately 1.5 miles north of its similarily named neighbor, Mt. Wilson, the two peaks comprise a part of what's known as the Wilson Group. The others being: El Diente Peak (unranked) and Gladstone Peak. Wilson Peak is the highest point in San Miguel County and one of the highest in the Lizard Head Wilderness and Uncompaghre National Forest.

Uncompaghre National Forest

1150 Forest Street

Norwood, Colorado 81423

#970.327.4261

USGS Maps: Mt. Wilson, Dolores Peak, Little Cone

USFS Maps: San Juan National Forest, Uncompaghre National Forest

Trail Illustrated: Map #141 Telluride-Silverton-Ouray-Lake City

Red Tape

This was writ in 1964 and has come to stand for the importance and signifigence of keeping the wilderness wild and virgin. The wilderness act when signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on September 3rd, 1964, legally defined what exactly constitutes a wilderness area. This act protected at its’ onset, some 9.1 million acres…Lizard Head Wilderness is but a pence in a huge coffer of coin.

There are four distinct Federal agencies that have, to varying degrees, jurisdiction over the existing wilderness areas and the new ones waiting to be established. These agencies are in order of scope: National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Game and the BLM. Since the laws governing wilderness areas are typically more strict and cumbersome than National Forest or BLM Lands, the following regulations pertain to climbing, camping, hiking and simple visits specific to Lizard Head: 1.) Motorized equipment is not allowed. 2.) In 1986, regulators expanded the definition of ‘motorized’ to include mountain bikes. 3.) Hang Gliders, carts or any vehicle with wheels are not allowed. 4.) Groups can be no more than 15 people in size, 25 with livestock. 5.) It is prohibited to build a fire within 100ft. of Navajo Lake, near any source of water or above tree line. 6.) All domesticated pets must be in control whether that means via voice command or leash. 7.) It likewise, is prohibited to camp within 100ft of Navajo Lake or any water source. And of course, as a compliment to future campers and hikers, please be considerate and remember to practice “Leave No Trace” ethics while backcountry. Other than that, all the red tape is pretty much non-existent!

The Rusty Nichols Debacle...

Wilson Peak is one of Colorado's famed "Fourteener’s"— the 54 peaks in the state that top 14,000 feet. In a state where mountain climbing is approached with almost religious fervor, many climbers make it a life's goal to summit all of the Fourteener’s. "They have a huge mountain feel," says Weihenmayer, who has climbed nearly 30 of them himself. Even in such lofty company, Wilson Peak seems special. Its thrusting summit is one of the best-known Colorado mountain images, used frequently in posters and advertisements, most notably for Coors beer. In recent years, however, the most accessible trail up Wilson Peak has been mostly off-limits to climbers. While most of the mountain lies within the Lizard Head Wilderness of the Uncompahgre National Forest, the summit trail traverses historic mining claims that remained private when the national forest was created early in the last century.

As the number of climbers has increased in recent years, tensions have built between them and the landowner, Rusty Nichols. At first, Nichols began requiring mountaineers to sign a liability waiver and pay $100 to cross his land. Then, in 2007, he closed the trail entirely. Nichols hoped to resolve the access issue by persuading the U.S. Forest Service to buy the land, or take it in exchange for valuable parcels nearby, but negotiations went nowhere. To break the impasse, TPL stepped in to option the property and facilitate an agreement that would reestablish climbing access to the peak. On hearing of this opportunity, Eric Weihenmayer offered to lead a climb that would call attention to TPL's efforts to protect access not only to Wilson Peak, but also to other Colorado Fourteener’s and recreation sites.

In Colorado, one sign of this demand is the number of climbers seeking out 14,000-foot peaks. About 60,000 people climbed a Fourteener in 1984, according to the Colorado Fourteener’s Initiative, a nonprofit that works to preserve the natural integrity of these iconic peaks. By 2004 the number had swelled to half a million annually, and the group predicts there will be one million Fourteener climbs by 2011. "The biggest problem with the increasing numbers is that Colorado's trails are not designed to meet that demand," says James Ashby, interim executive director of the Fourteener’s Initiative. Heavily used routes become widened, incised, and braided. Sometimes hikers strike out across fragile tundra and alpine vegetation, which can take decades and even centuries to recover. In the face of this demand, groups like the Colorado Fourteener’s Initiative have helped to reroute or rebuild worn-down trails. The Forest Service also works to mitigate the impact of hikers on sensitive alpine environments.

But one of the biggest management issues arising from increased visitation is maintaining any kind of access, especially where trails cross private land. Trailheads, climbing approaches, or in a few instances the summits of six Colorado Fourteener’s are located on privately owned mining claims. To encourage economic development in the West, 19th-century mining laws made it easy to "patent" a claim for a few dollars. And while most small, high-country claims are no longer worked for minerals, many of them could be developed into second-home or cabin sites, blocking access to areas that help support Colorado's $10 billion outdoor recreation economy.

Historically, Fourteener hikers and climbers have trespassed across private mining claims—trespasses that were largely ignored when visitor numbers were low. But the recent tidal wave of peak-baggers has caused some landowners, like Rusty Nichols, to worry about vandalism and theft—and about liability in an increasingly litigious society. At several Fourteeners, tensions between hikers and landowners gradually built, coming to a head in 2005 when a handful of landowners in the Mosquito Range, southwest of Denver, announced they were shutting off access to their peaks.

Then, in 2007, Rusty Nichols closed the popular Wilson Peak trail. Nichols, a Texas real estate developer, bought his first mining claims beneath Wilson Peak in 1978, as a getaway location. The parcels included a miner's cabin from the turn of the 20th century, when as many as 500 gold miners worked in the Silver Pick Basin, on the northwest side of the mountain. "I was looking for privacy and a place I could take my kids camping," Nichols says. He eventually bought up several other patented claims, initially to buffer his property from other potential mining operations. But he also hired a geologist to assess the land's mineral value and learned that remaining gold veins might make mining worthwhile. "Mining was always an option, and a lucrative one," Nichols adds.

In the years following Nichols's land purchases, Telluride's growing reputation as a recreation destination attracted skiers, hikers, climbers, and other outdoor enthusiasts. Demand for second homes fed a steep rise in real estate prices. "Early on, I would go up there with my sons for a week at a time and maybe see three or four people," Nichols says. But by the late 1980s, he estimates, more than 100 people a week were coming through his land during the summer. That's also when the trouble started. He says now that vandals cut hydraulic tubes on his vehicles, filled gas tanks with gravel, and even burned down a small cabin. The sheriff's office was called several times to mediate disputes. Based on his estimate of the mineral value, Nichols had been trying without success to swap or sell his land to the Forest Service. Frustrated by this stalemate and the vandalism—and even as he began to charge climbers to cross this land and then bar them entirely—he let it be known that he was considering mining in the Silver Pick Basin, which would have severely limited access and potentially caused significant environmental damage.

Staffers for TPL-Colorado had been observing the conflict from a distance. Since 2001, TPL had been partnering with the Forest Service to acquire 8,000 acres of patented mining claims in the area of Red Mountain Pass, 20 miles east of Wilson Peak. "This gave us incredible experience tackling thorny title issues," says TPL project manager Justin Spring, who has worked to retire former mining claims both at Red Mountain and in the High Elk Corridor, near Gunnison, where TPL has helped add more than 1,700 acres to White River National Forest. "We always wondered if there was a way for TPL to jump in and be the hero at Wilson Peak," Spring says.

In 2006, former TPL project manager Jason Corzine reached out to Rusty Nichols to see if a way could be found around the impasse at Wilson Peak. As an independent nonprofit, TPL was able to raise donated funds for the project. For Nichols, one of the keys to the eventual agreement to protect climbing access was that TPL "recognized the value of minerals that are still out there. They did everything they said they would. I have very high praise for their professionalism."

As part of its initial agreement, TPL optioned 230 acres—23 mining claims, including the summit of Wilson Peak. Then the staff began the hard work of surveying, getting appraisals and environmental assessments, and conducting negotiations and fundraising. In October 2007, TPL bought the property, using donated funds and a crucial loan from the Colorado Conservation Trust, and hopes to transfer it to the Forest Service within the next few years. Nichols will retain 77 acres, including his cabin site, under a deed restriction that prohibits mining and limits residential development. "Bringing in a partner like TPL brings a couple of things to a project," says Corey Wong, a Forest Service public service staff officer for the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests. "They do have more tools than we do and more relationships."

With its ability to leverage donations, TPL acted with a swiftness that a government agency could not, Wong says, adding that the organization also acted as intermediary in the strained relationship between Nichols and the Forest Service. Support for TPL's $3.25 million purchase of the land came from the Colorado Mountain Club Foundation, Coors Brewing Company, Lynne and Joe Horning, Dan and Sheryl Tishman, San Miguel Conservation Foundation, the Telluride Foundation, and numerous other individual donors.

The permanent protection of Wilson Peak has inspired generosity from local donors and from people who've only seen the mountain's image," said Tim Wohlgenant, TPL's Colorado State Director. "Now we are working with our partners in the U.S. Forest Service and the climbing and mountaineering communities to relocate the main trail and officially restore access." One key project supporter was the Colorado Conservation Trust (CCT), a statewide community foundation for conservation. Doug Robotham, former director of TPL's Colorado office and a deputy director at (CCT), says that TPL's work to protect the Fourteener’s will further the recently launched Colorado Conservation Partnership Project. "TPL and CCT are working with other groups to protect 24 of Colorado's most cherished natural and cultural landscapes—the best of the best," he says. "The Wilson Peak region and the Mosquito Range are included, in part because access to the 14,000-foot peaks is so critical to experiencing what it means to live in or visit Colorado." Wilson Peak is the first Colorado Fourteener where access has been purchased from a private landowner and will be restored to the public. TPL hopes to duplicate the effort elsewhere in the state. (The Trust for Public Land, May 1st. 2008)

Recent Developments

Release Date: Aug 3, 2011 Contact(s): Judy Schutza, District Ranger, U.S. Forest Service, 970-327-4261, Jason Corzine, Project Manager, The Trust for Public Land, 303-501-5570 Norwood, CO., (August 3, 2011) – The Forest Service announces the opening of the new Rock of Ages Trail, located about 15 miles southwest of Telluride, Colorado. Opening this 3.7-mile hiking trail concludes a seven-year effort by the Forest Service and other organizations to restore public access to Wilson Peak, a popular “fourteener” in the Lizard Head Wilderness.

A trail map and directions to the new Rock of Ages trailhead are posted on the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forest website at www.fs.usda.gov/gmug under “Highlights”. “We are thrilled to open this new trail that will allow climbers to hike through Silver Pick Basin on their way to Wilson Peak” said Judy Schutza, Norwood District Ranger. “Public access would not have been restored without the efforts of The Trust for Public Land who purchased key private parcels on Wilson Peak and in Silver Pick Basin.”

In July of 2004, a traditional route to Wilson Peak through private lands in Silver Pick Basin was closed. During the ensuing years, the Forest Service joined forces with The Trust for Public Land (TPL) to restore public access. San Miguel County, the Telluride Mountain Club and the Colorado Mountain Club were also key players in this effort. In October of 2007, TPL took a significant step toward restoring public access by purchasing 230 acres of private land in Silver Pick Basin, including key parcels on the southwest ridge of Wilson Peak. The Forest Service made further progress in August of 2009 by completing the environmental analysis for the Rock of Ages Trail, however a trail easement across a private parcel in the upper basin was still needed to fully restore access.

In May of 2011, the Forest Service obtained the needed trail easement. Construction of a new trailhead parking facility and access road were completed this week. "We're very excited to have reached this most important stage in the process," said Jason Corzine, Senior Project Manager with TPL. "Restoring and preserving public access to this iconic peak has been TPL's main goal from the beginning." TPL continues to own the property they purchased in 2007 and is working to convey that land to the Forest Service. Wilson Peak is among three 14,000-plus foot peaks in the Lizard Head Wilderness that annually draw thousands of climbing enthusiasts. The new Rock of Ages Trail provides a shorter route to these peaks than is currently offered by existing trails. (USDA Website).

Getting There

Wilson Peak has three main approaches. The first is from the north via Silver Pick Basin, sometimes called Rock of Ages. The second approach is from Sunshine Mesa which grants access to Bilk Basin (from the southeast). A third, but somewhat longer approach is from Woods Lake to the west. A fourth option is to approach from the south via Kilpacker Trail and Navajo Lake. This is a long option but will grant access to all the 14ers (and other peaks) in the area. There are several other trailheads/approaches that can be used and linked up, but they generally serve the other peaks in the area. In terms of proximity, only those liosted will be detailed.

■ Rock of Ages

Also known as the Silver Pick approach stemming from the mine located at the head of Fall River Creek, the Silver Pick Mine, this is the most efficient and direct route to gain the summit of Wilson Peak. It is class 2 the entire way to the Rock of Ages Saddle (13,000ft) and thanks to some very hard and ongoing work by the CFI in surmounting the obstacles that local land owner, Rusty Nichols made difficult for the climbing community, this approach can be considered a viable avenue again with some minor detours along the way including an entirely new trailhead (opened in August of 2011).

This approach is roughly 3.75 miles roundtrip to the saddle. The new approach directions as listed below are taken from 14ers.com with Bill Middlebrooks’s permission. For a more detailed description that includes associated pictures, please visit Bill’s page (14ers.com) on this subject.

“From Ridgway, leave U.S. 550 and take Colorado 62 towards Telluride. Drive over Dallas Divide and down to the town of Placerville. Turn left onto Colorado 145. Drive 6.5 miles and turn right on the Silver Pick road. It is 6.8 miles from here to the trailhead. From the start of the road, drive 3.1 miles to an intersection. The sign says "Silver Pick Basin - 5". Stay left. After another 0.7 mile, there is a confusing intersection. Do not continue on the road that goes straight. Turn right a bit to see the road that you want. Do not take the road that takes a hard right (it has a Private Property sign). Drive into the National Forest after another 2.2 miles (6.0 miles since you left Colorado 145). After another 0.1 mile, turn right onto FR 645 and continue approx. 2.25 miles (there are some possible campsites along the way) to the new Rock of Ages trailhead near 10,350’. From the new Rock of Ages trailhead, hike south and then southeast on the Rock of Ages (#429) trail to enter Silver Pick Basin near 11,300'. Continue southeast up into the basin. Continue on the road as it climbs south into the basin. Near 11,500', cables (on the ground) from an old ariel tramway become evident. The road parallels the cables for a while and briefly turns right (west) near 11,800'. The road soon leads back to the center of the basin. Stay on the road as it climbs east and then south to the top of a small hill with the remains of a rock house. From the rock house, you will need to do some brief route finding. Look directly south up on the steep slope to see the remnants of the Silver Pick mine. Just to the left of the mine, locate a dirt "trail" that leads up to the mine. From the rock house, walk across and then up some talus. There's not a great trail here, just continue south up talus until you spot the best way to reach the base of the slope. Locate the loose trail and climb approximately 450' to the left side of the mine. Near the mine, find a better trail that heads left (southeast). Follow the trail across the steep slope to reach the "Rock of Ages" saddle near 13,000'.”

■ Bilk Basin (Sunshine Mesa)

Leaving the town of Telluride, head west on Co 145 for about 2.5-2.6 miles. They’ll be a sign for South Fork Road on the left side (south) and a tourist outdoors camp called Camp Ilium. Head down and cross over the San Miguel River on a small wooden bridge after 0.2 mile. Simply follow the road as it courses south. After 2.0 miles, look for the Sunshine Mesa Road turnoff (FR 623). Turn right (west). The road will climb gradually for roughly 7.6 miles with a couple of descents thrown in. Sunshine Mesa Road will dead-end at the trailhead at mile 7.7. This trailhead is at 9,800ft. This approach accesses Wilson Peak’s east flanks and is not maintained in winter. For a description of the entire trail from the Bilk Creek Trailhead, go here. This trailhead can also be used to climb Gladstone Peak.

■ Woods Lake

From the junction of Co 145 and Co 62, drive east for 2.7-2.8 miles on Co 145 passing through Placerville. Look for a signed road on the right side saying Fall Creek Road (57-F Road). This will be your exit. Turn south crossing the San Miguel River at 0.1 mile and set your odometer. Continue driving south and southwest for roughly 4.0 miles. At mile 4.0, turn right and continue to drive straight ignoring the side roads. Pass a small intersection at mile 6.0 and again at 7.8. At roughly 9.0 miles, there will be a forest service sign indicating Woods Lake Campground. Pull into the campground and look for the separate area used for trailhead parking (it’s quite ample). This trailhead starts at 9,352ft and provides access to El Diente, Wilson Peak and Mt. Wilson via Navajo Lake/Basin.

The trail (#406) winds around Woods Lake within a quarter-mile or so of the trailhead then zigzags across a few small streams in its first 3 miles through the thick forest. The climbing initially is steep and somewhat steady until the Woods Lake Trail meets the Elk Creek Trail in an open hillside just above treeline (make sure you have your camera!). The flies and mosquitos on this very green and tranquil approach can be horrendous in late summer but the view of El Diente as one finally crosses the saddle that descends into Navajo Basin is intoxicating!

■ Kilpacker Trailhead

Sitting at a respectable 10,060ft, Kilpacker is the trailhead of choice for most El Diente ventures and ascents because of its relative proximity to the mountain. Kilpacker provides access to the southern routes for El Diente and the southwestern slope for Mt. Wilson. Convenience is high for this portal. Travel south from Lizard Head Pass on Co. 145 for roughly 5.5 miles. Turn right (west) onto FR 535 (Dunton Road). The drive from the trailhead from this point can be a bit convoluted but persist! The dirt road will slowly climb in a northwestern direction. There will be a bit of a ‘rough intersection’ at mile 4.2. Keep driving straight through this. At 5.0 miles, turn right onto FR 207. The trailhead is only another 0.3 miles. Dunton Road is NOT plowed or maintained in winter but the frequent snowmobilers will make life easier for a short while! Parking can be tight.

Camping

Without making this section needlessly too long based on which approach one is going to use since Wilson Peak, Mt. Wilson and El Diente can all be day-tripped from every trailhead, I’ll explain a little about the most used areas for camping.

Probably hands down the one area most people use to camp for these three peaks is Navajo Lake located at 11,120ft. This pristine lake located just below treeline is situated 0.3 west of El Diente and 0.45 miles west of Mt. Wilson. Wilson Peak (and the Rock of Ages saddle) is roughly 0.7 miles from Navajo Lake. There are ample sites available to camp around the lake with additional sites located 0.1 mile ‘up-valley’ on its’ northern fringe. Most of the sites are located across the outlet where the trail first meets Navajo Lake on its western end. Just look for and utilize existing fire rings to avoid degradation of the forest since this is a wildly popular destination in summer. A few camping sites don’t allow fires but these, the last time I was up there were signed as such. Just remember to practice ethical camping habits so future campers can equally enjoy this beautiful and sheltered basin.

Camping of course is also an option at Woods Lake Campground. Hiking and climbing these Fourteener’s in a day from Woods Lake will be a bit of a stretch but is quite doable as a long day. The campground, located 0.4 miles from Woods Lake and 0.75 miles from Lizard Head Wilderness is situated in multiple thick stands of Aspen. It is comprised of three loops, one of which is designed for horses. This horse loop has a corral with five paddocks and a watering trough. A large parking lot is available for parking horse trailers.

The campground is an excellent base camp for hikers and horses to access Lizard Head Wilderness. There are incredible views looking south from the campground of mountains in Lizard Head Wilderness. And, of course, the "quaking" leaves and majestic fall colors from the Aspen, add to the draw of this campground. The campground is $14.00 per day with a 2 week maximum stay. This is a seasonal campground opening its gates around late May and closing mid-September. Tables and grilles are available, vault toilets and fishing is allowed (Cutthroat and Rainbow). There are four water spigots but no public phone or flush toilets. This is a first come- first serve campground. There is also car-camping at the Kilpacker Trailhead but this is limited to the spaces available. I’ve yet to ever run into a problem (twice) doing this.

Mining

Of all the industries and institutions to define the west during the imperialism decades it's undeniable the mining is among the most indelible. Even nature has a difficult time of it trying to erase the scars of mines, slag piles, structures, stopes and tailings to name but a few. And I won't even touch the effects that chemicals and leaching agents have played on the environment and still do to this day. Unfortunately, not many places in Colorado have escaped the depredation of mining. Regrettably, the San Juan Mountains have suffered some of the most acute devastation, including the Wilson Mesa area to say the least.

Colorado has over 300 ghost towns sprinkled between its borders. Impressively, that's a third as many "living" towns still harboring populations. One could probably make the case that mining is a kind of 'pioneer industry' in that, it eventually brings in other forms of infrastructure and commerial necessitation. Industries like: ranching (cattle and sheep), homesteading , the railroad, liquor (saloons), and general commerace owe mining, in no small part, a portion of their existance and exigence.

Many towns and cities in Colorado have taken their names from the ore that was mined locally. Places like: Silverton, Silverplume, Argentine, Silver Dale, Gypsum and Leadville leave no doubt as to what was mined.

A smattering of elements like: nickel, lead, molybdenum, marble uranium etc. have been taken from the hills. However, in the mid-1870's, gold was starting to come into its own and in 1874, the San Juan Mountains experienced a sizeable gold rush that lasted close to 35 years. Even though gold, silver and the like drew thousands to the Colorado highcountry in search of riches and dreams, there is no doubt that proprietors of bedroom industries like hospitality, drink and prostitution equally prospered.

Many people however, died quietly and faded into the mountain sides like aspen leaves. The only life remaining in some of these lonely places is the barks of curious marmots or the occasional throttle of an ATV or Jeep. Nature is slowly taking back what was always rightfully hers. Rising costs, weather, declining profits (supply and demand) and two World Wars effectively ended Colorado’s mining era. The skeletons of these orphaned dreams and lost passions still remain. Of all the mountain ranges and sub-ranges in Colorado that supported mining (keep in mind, not all areas are pocked and torn from mining), the San Juan Mountains were unequivocally the largest.

Below is just a small sample of what lies within the vicinity of the Wilson Peak, Mt. Wilson and El Diente.

■ SAWPIT

A Blacksmith was the driving reason why Sawpit came into existence. The ‘smithie’, James Blake, found relatively high-grade ore in the placer and further up on the mountainside while on a scouting trip in 1895. Once a mine was dug and validated, he named him stake the “Champion Belle”. The first three loads of ore alone netted him almost $1,800 to say nothing of the following 35 loads. The floodgates opened once word got out and other would-be prospectors permeated the valley.

By 1896, another major mine was opened within shooting distance of the Belle…the Commercial Mine. Saw Pit became incorporated. I’ve read how Saw Pit was named for a nearby creek but I’ve also read how the name was derived from a rather ‘larger than usual’ saw pit on site. Saw Pits were used by the miners to basically half felled trees and lumber. One miner would hold one end of a large saw atop the pit while the other would jump down into the hole and grasp the other end and hope he didn’t get crushed. The fortune days of Saw Pit last until roughly 1905 before things started to dwindle. Now, all that’s left is some rag-tag buildings and perhaps the odd, covered foundation.

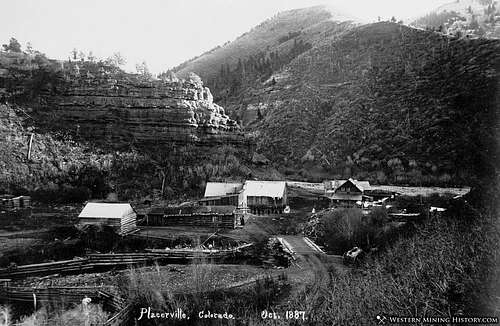

■ PLACERVILLE

Placerville was named for the obvious placer gold found here. Even after the gold dwindled and disappeared from the creek, the small town kept battling for life through the years, holding onto its name; fact, a small contingent of people still live here. A prospecting party in 1876 from Del Norte led by Colonel S.H. Baker is generally credited with finding gold here.

Come 1877, the rudimentary beginnings of a mining camp began to take hold. But Placerville’s start wasn’t as cut and dry as most other mining towns. If anything, the growth and movement of Placerville illustrated how flexible the miners could be gold, whisky and supplies were on the table. Even though some cabins and various foundations were either already built or laid down, the progenitor of the saloon and general store didn’t like the original location. There was a better spot about 1.5 miles further up-valley that this gentleman liked better. So he tore what infrastructure he had down and moved his businesses up-valley. Ordinarily, this wouldn’t have been a problem since more than one individual usually built a saloon or gaming hall.

However, this was Placerville’s ONLY saloon and General Store. So since going without supplies or libations simply wasn’t an option, the miners pulled up their stakes and relocated 1.5 miles further up-valley to be in the vicinity of the saloon and commerce.

Placerville grew slowly but steadily throughout the late 1800’s. Another odd twist is that Placerville’s ‘growth spurt’ didn’t come for nearly another 10-12 years and it wasn’t gold that spurned the influx but rather, ranching. Cattlemen came first seeing the potential in the area’s fields, meadows and high plateau’s.

A few years later, the real problems began…sheep herders came to town. The cattlemen hated the sheepherders. There were about 3-4 years in the early 1900’s where the violence between these two groups threatened to override the town. Fighting became a daily occurrence over the pastures. Eventually, the two learned to live with one another. In 1904, a massive flood nearly wiped out the entire town (probably due to spring snowmelt).

To give you a small comparison, this same year, 1904, F.O. Stanley and his wife (Flora) had just moved to the small town of Estes Park for the summer. The Stanley Hotel would come after another five years. A fire nearly destroyed much of Placerville in 1919 but resiliency took over and the town was rebuilt. Due to the mines in the area which, produced almost 30% of the world's vanadium, this industry remained vibrant through 1940. Due to the large parcels of private land that surround Placerville now, expansion is guaranteed to never happen. The town will probably never grow beyond its current borders. However today, Placerville is a small but thriving community with a nice town park (and small lake), a local plumbing and moving company are located here and the popular M&M Merchantile that has been there since 1920.

■ FALL CREEK

Also referred to as Seymore and Silver Pick, during the 1890’s, Seymore was a busy mining camp located on Fall Creek. It served as the main hub for all the ore coming out of the Silver Pick Mine further up Fall Creek near Wilson Peak. It supported multiple buildings including a post office, a few saloons, general mercantile and even a small hotel. For whatever reason in 1894, the post office was actually moved TO the Silver Pick Mine. Two years later, it was relocated to the town of Saw Pit. It officially changed its name to Fall Creek in 1922. The name, ‘Fall Creek’ is simply a general term for a river or creek that seems to have an overabundance of waterfalls.

■ SAN MIGUEL

Located a few miles down-valley from Telluride, San Miguel (Spanish for Saint Michael) rivaled Telluride for a short spell in terms of rowdiness, population and popularity. The town had a very decent gold and silver mine located nearby and cattle were a daily aggravation that just had to be tolerated. Telluride never really suffered this problem at least, not to the extent that the lower altitude towns did. What San Miguel did have going for it were excellent foundations. The town was laid down very smartly and conservatively. Not too many trees were cut down nor was the creek diverted. However, in the end, Telluride won out. San Miguel was a bit too placid.

■ MEGA

A one-time and short lived settlement located near Placerville but its exact location is sketchy at best. The town’s odd name (for a mining camp) came from some of the settlers opinions that “this was it”. Being the last letter in the Greek alphabet, the connotations that Omega was the last town for gold were apparent. It lasted roughly 10 years.

■ VANADIUM

Located up-valley from the Belle Champion Mine, Placerville and Fall Creek, Vanadium was little more than a rag-tag, rough mining camp. The town grew around a huge mill operated by the U.S. Vanadium Corporation. Like Omega, it too experienced a tragically short lifespan but buildings still exist including the old post office. I’ve seen other town names mentioned in some of my readings like: Hangtown and Dry Diggings but I have yet to actually come across any information on these ‘towns’. This is a common theme in the mining years throughout Colorado. Towns will literally spring up overnight only to disappear after 6 months to a year, give or take. Usually the gold will play out, the claim(s) end up proving unfruitful, weather or snow will force people out or distances needed to travel to attain supplies is too great. In such instances, I’m inclined to think that these homesteaders/miners set up nothing more than small encampments.

Mining...

Within the Lizard Head Wilderness, there are a total of 109 mines (all closed). Although I'm sure there are probably a fair number of forgotten exploratory shafts. Not all the mines produced ore in great quantity. Most were actually low-producing mines that kept operations running but barely profitable.

Within the Wilson Peak Minig District, located in Dolores County, there are no fewer than 30 mines (again, all closed). The history timeline in the vicinity runs from 1880 to around 1961 when the last producing mine, The Silver Pick closed. Most ore occurances in the area were of fissure veins or widespread vein disseminaton. The primary ores mined were: Au (gold), Ag (silver) Pb (lead), Zn (zinc), Cu (copper) and Zn (zinc).

The following is just a small sample of what was in the immediate area.

- Silver Pick Mine- Located on the upper Wilson Mesa, this mine operated from 1882-1961 with consistantly dwindling percentages. The ores extracted from this mine were: Au, Ag, Cu, Pb, Zn, Sb (antimony).

- Wheel of Fortune Mine- Initially discovered and claimed by John Ross in 1886, this mine operated from 1887-1937. It produced ore of varying quality of gold, silver, zinc and copper. It is located WSW of the Rock of Ages Saddle at an altitude of 11,740'.

- Synopsis Gold Mine- Located on the western slope of Wilson Peak, this was small operation. I is located at an altitude of 12,759' and resulted in small amounts of gld, copper and lead. The original claim owner is unknown.

- Wilson Peak Mo Occurance- The origination of this mine is unknown but is thought to have started in 1880. It is located due south of the Rock of Ages Saddle and produced Mo (molybdenum) and copper.

- Rock of Ages Mine- This is probably one of the better known mines in the area. The saddle located between Wilson Peak and unnamed 13,540' takes its' name from this mine. When in operation, ore output was small but consistant just enough to keep the mine open. This mine has also been known as the Peak View and the Rock of Ages Millsite. It is located at an impressive height of 12,861'. Per metric tonne, the ore consisted of: 0.04% oz- Au, 0.54% oz- Ag, 0.52% oz- Cu, 0.26% oz- Pb, 0.10% oz- Zn

Accidents/Rescues

As with any sport or physical hobby, accidents can and do occur. Sometimes, if the sport is hazardous onto itself or if the participants engage in reckless behavior, serious accidents or death can occur. And as with any sport that sees an increase in popularity, the odds and percentages go up that eventually, something WILL happen. Wilson Peak is definitly NOT without its share of accidents and tragedy.

The Most Dangerous Fourteeners in Colorado (Colorado Westword)

- September 28th, 2020- In the late morning of Saturday, Sept. 26th, a local Telluride-area man climbing solo sustained a fall down the East Face of a "significent distance." He came to rest around 13,300'. Search & Rescue and local emergency teams responded & reached the fallen climbed around 1:42 pm via helicopter. The injured hiker sustained severe head injuries and other injuries associated with rockfall. The rescue consisted of teams from: Telluride Fire Protection District, San Miguel County Sheriff's Office, Careflight & numerous SAR Volunteers. The rescue was coordinated on low-angle rock and necessitated the use of ropes and a liter for extraction. The unidentified male was then transported to St. Marys Hospital in Grand Junction.

- September 10th, 2009- Not hiking or climbing related, but after three years of searching by San Miguel officers, the body of a Dallas, Texas man was recovered from Wilsons' slopes. The small plane he was flying crashed into the mountain killing all three people aboard (including the pilot). It is believed they were en-route to the Telluride Blues & Brews Fetival in September of 2006. This is an interesting article. Telluride Daily Planet.

Great Video in 4K

Topographic/Terrain Map

Miscellaneous

Diggler - Jun 28, 2012 7:02 pm - Voted 10/10

Great page- here is a map linkThanks for putting up a great page for this superb peak. Regarding the new Rock of Ages Trail (#429), here is a link to a .pdf of the forest service map- I think this would be helpful for those desiring a current map: http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5320677.pdf

Kiefer - Jul 1, 2012 12:05 am - Hasn't voted

Re: Great page- here is a map linkThanks for taking a look and I appreciate the great comment! I like that map you included and I will include it on the main page. Hopefully, I'll get around to doing it tonight or tomorrow. Thanks, Diggler!